Wayne Biddle

- 1988

Fellowship Title:

- Corporate History of Defense Spending

Fellowship Year:

- 1988

Cold War Resartus

Whether or not the endless winter of menace known as the Cold War is actually over, it already seems bracketed in history. At the beginning was competition between Washington and Moscow for politico-economic control of a destitute Europe, lethalized by the spread of atomic bombs. At the end was rebirth of pre-World War II European nationalism, occasioned by Soviet and American economies too exhausted or debt-ridden to maintain the old fever-pitch contest. In between were some of the century’s nonsensical grotesqueries: McCarthyism, Quemoy and Matsu, the Berlin Wall, Star Wars. The only constant was the atom bomb. The bombs, of course. are emblematic of an armaments industry that has come to feel as second-nature to many Americans as television and computers. That the United States did not possess a constantly replenished arsenal before the Cold War has been lost from common memory. Indeed, the popular assumption that the modern weapons business grew solely as a military response to the Soviet threat–hence “defense” industry–is taken so much for granted that an examination of what the founders

How America Eagerly Built Her Arsenal

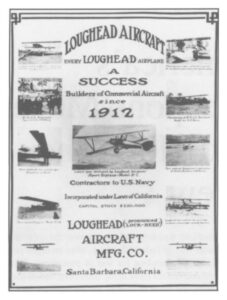

Since Pearl Harbor, the United States has been in a constant state of either fighting or preparing for war, a strange fate for a liberal democracy that has allowed the military to have enormous influence on our way of life. New revelations this year about crime in the weapons industry resonate strongly because America has entwined so many of its essential attributes with warfare, for better or worse. Although the foundation for vast military-industrial power grew during World War I and throughout the next two decades, the structure was permanently secured by the Second World War. It is to those years that one must turn to understand why efforts at disciplining the way the U.S. arsenal is purchased have never brought much change. By 1939, a handful of aviation companies had struggled through the Twenties and Thirties nurtured by relatively small but profitable military contracts. The Great Depression had come just as a few firms were beginning to cultivate a civilian market for their aircraft, capitalizing on the public’s fascination with Charles Lindbergh’s 1927 transatlantic

America’s Weapons Makers and How They Grew

The American weapons industry is over the crest of another roller-coaster ride of federal funding, after an eight-year climb to unprecedented spending for war in peacetime. Though the Presidential candidates have made little commotion about what happens next, the issue of money for the military lurks around the next bend in the nation’s troubled economy. There have been so many twists and turns in this debate–from John Kennedy’s “missile gap” to Ronald Reagan’s “evil empire”–that ordinary people may wonder where the tangible parts are. Meanwhile, building weapons has become one of the identifying features of our society, like skyscrapers and computers. How did this get started? Are we any better today at managing such a perilous but coveted business than 25 years ago? Than 75 years ago? Most discussions about the modern weapons industry use the 1950’s as a starting point. East-West tensions and the spread of nuclear arms caused World War II combat merchants to continue thriving, instead of withering as was the usual course after major conflicts. But the rise of some of