On the afternoon of Saturday, May 4, 2001, the cast of the Monadnock Regional High School production of “Ordinary People” gathered in the school auditorium in Swanzey, N.H., for its first dress rehearsal. Opening night was only four days away, and the mood was strained and occasionally hostile. The problem, most of the cast agreed, was an angry Greg Kochman, who played the lead role of Conrad, a suicidal teenager coping with the death of this older brother.

Greg, then a junior at Monadnock, was in one of his moods. “He was so angry that week, and that day was the worst of it,” recalls Christen Arrow, who played Conrad’s mother in the play. “He would just lash out at people for no reason.”

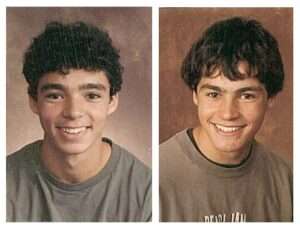

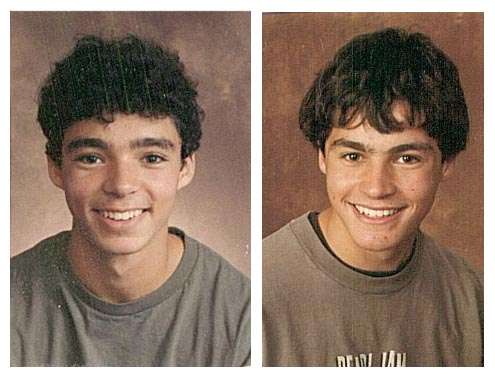

Still, there was no denying that Greg could act. And on Saturday, the broad-shouldered, dark-haired 17-year-old was acting even better than usual. “Then I sit down and think about – things,” Greg, playing the role of Conrad, said. “Everything that hurts. And I cry. Inside, I’m burning up. Outside – all I can feel is the cold tile floor. And my chest feels so tight – it hurts – everything hurts – so I hold out my hand and close my eyes – and I slice, on quick cut, deep cut.”

Katherine Depew, who played Conrad’s therapist in the play, had never heard Greg say the lines so well. “He said it static, monotone, and it was the best he had ever done. It was eerie.”

That’s because “Ordinary People” – based on the novel by Judith Guest, which was later made into an Academy Award-winning movie directed by Robert Redford – was supposed to be therapeutic for Greg, After all, Greg was, like Conrad, deeply depressed over the death of his popular and well-liked older brother. Like Conrad, Greg was seeing a therapist. Like Conrad, Greg already had tried to kill himself.

Theater, it seemed, was going to save him. “Greg loved the role of Conrad,” recalls Casey Gallagher, then a Monadnock senior who considered Greg his best friend. “He needed that role. He was acting out what he felt for his brother.”

But the play didn’t make Greg any less sad. The day before Saturday’s dress rehearsal, he broke down crying in the school auditorium. Saturday wasn’t much better. “By the end of rehearsal,” recalls Depew, “I just wanted to go somewhere a little more positive.”

As Depew left the auditorium, Greg, who was sitting in the first row, told her he loved her. “He had never said that to me before,” she says. “But I was so frustrated with everything, I just said ‘Bye’ and went to the parking lot to get my car.”

Depew and Arrow went to dinner by themselves, where they spent most of the meal complaining about Greg. Gallagher and Jordan Self, Greg’s best friends that year, thought about inviting Greg out with them, but decided against it. “I was like, ‘Okay, this is leave Greg alone time for a little while,'” says Self. The boys went to a friend’s house, where they spent the night playing video games and doing doughnuts in their friend’s truck in a nearby field. As they headed back to Self’s house, they almost called Greg. “But we were both tired,” recalls Self. “We wanted to go home and make nachos.”

Greg’s father, David, and his wife, Sandy, got home from dinner with friends at about 8:30. Greg’s 1994 Ford Escort wagon was in the driveway, but he wasn’t home. Greg was scheduled to work at 6 a.m. the next morning at Colony Mill, a marketplace in Keene. When David went into Greg’s room to wake him at 5 the next morning, he found an empty bed. David walked downstairs, where he looked out the window and saw Greg sitting in a plastic lawn chair by the pool.

What David could not see from the window – but what he would discover when he walked out back – was that his youngest son, like his oldest son a year before, had fatally shot himself in the head.

David Kochman is a short, athletic man with curly black hair and a mustache. He is punctual, polite, friendly, and disciplined. When he laughs, which he does often and unexpectedly, his face scrunches up, his shoulders bob up and down, and his mouth emits rapid-fire chuckles. He is not an emotional man. Until Eric’s death two years ago, he had never cried as an adult.

When his boys were young, David, who works for an insurance company, spent much of his free time shuttling them to and from soccer matches, baseball games and weightlifting events. When David and his boys weren’t talking about sports, it’s a good bet they were discussing politics. David, Greg, and, to a lesser extent, Eric, attended New Hampshire Republican fundraisers and political dinners. “Eric and Greg were always busy doing something,” says the boys’ mother, Rose. “It was nonstop.”

In September of 1997, Rose and David told the boys, then 15 and 13, that they were separating after 17 years. The brothers seemed unfazed by the announcement, and even their friends were unsure how it affected them. David and the boys sold the family house and moved into a three-bedroom condo, and Rose moved into a one-bedroom apartment nearby.

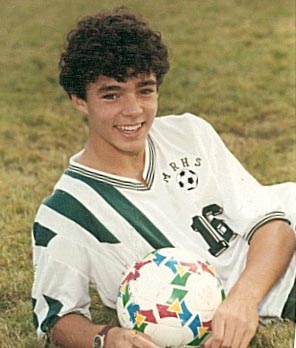

It was about this time that the brothers, already talented soccer players, became local celebrities of sorts in power lifting. In an article about the boys in the local Star Spangled Banner, Greg said he was shooting for his older brother’s state record. “He’s never going to do it,” Eric countered. “Although I can’t imagine losing the record to any better guy.”

The quote was typical Eric: Cocky, and respectful of Greg. One of the most popular students in school, Eric – tan, well-built, with long eyelashes, and curly black hair – had many friends, but none meant more to him than his little brother. “Their favorite song was ‘Siamese Twins’ by the Smashing Pumpkins, and in many ways that’s the way they saw themselves,” says David. “They were inseparable.”

They also were different. Eric was a classic extrovert – outgoing, popular, funny, emotional, and, at least on the surface, sure of himself. Greg was studious, disciplined, and not as gregarious, although he shared Eric’s ability to make people laugh. (Greg’s imitation of Austin Powers could bring people to their knees).

Greg always was the better student. He was a voracious reader and finished all of John Grisham’s books by the sixth grade. While also an avid reader, Eric was a “B” and “C” student prone to skipping school or sleeping through a morning class if the mood struck him. Eric’s focus always was on sports and friends, which he never lacked. Eric opened social doors for Greg, and many of Eric’s friends became Greg’s friends, too.

“We’d take Greg with us to parties, and Eric was always protective of Greg,” says Kris Kesney, a close friend of Eric’s in ninth and tenth grades. “Greg was the innocent little child. He was shy and seemed insecure a lot. Eric was the partier. We used to drink a lot. Like most people around here, Eric liked to get fucked up.”

According to friends, Eric started drinking and smoking marijuana late in junior high. In eighth grade, the school reprimanded Eric after he was caught drinking from a hair spray bottle that a fellow student had filled with alcohol and brought to school. In ninth grade, Eric was suspended for two months when a fellow student’s parents complained that Eric had helped their child get marijuana.

Still, Eric was one of the most popular and well-liked students at Monadnock. “He was nice to you whether you were popular or not,” says then Monadnock senior Tim Wilder. “He was in the group with the snobs, but he wasn’t a snob at all.”

At home, Eric and Greg were polite and respectful. The family usually ate dinner together, and the boys had a deep respect for David, whom they called a “genius.” Still, friends said the boys’ relationship with their father was mostly superficial. Like many dads, David was more comfortable talking to his boys about baseball than the complexities of real life. “David isn’t comfortable taking about feelings,” says a friend of the brothers, “and I guess Eric and Greg just followed his lead.”

The boys differed greatly in their relationship with their mother. While Greg did not get along well with Rose, particularly in the last year of his life, Eric routinely stopped by Rose’s work to talk. “And he would always give me a big hug and say, ‘I love you mom,’ right in front of everybody,” recalls Rose. “And people were flabbergasted. Other mothers would say, ‘My God, if my son would only say that to me!”

* * *

Like many victims of serious depression, Eric Kochman didn’t look depressed. He made his first and only plea for help in July, 1999, as he walked along Hampton Beach with his mother. “Eric looked at me and said, ‘Mom, I have a chemical imbalance,'” recalls Rose. Knowing little about mental illness or clinical depression, she assumed Eric was talking about his hormones. Eric shook his head. “Mom, it’s not that.”

Rose says she pressed him for details, but Eric was reluctant. They agreed that he should see a therapist, but Eric told Rose that he didn’t want anyone, including his father and brother, to know. It was a telling request: Eric couldn’t stand the thought of people knowing he wasn’t perfect.

The next week, Rose accompanied Eric to the office of Monadnock Family Services, a community mental health agency in Keene. It was there, David would later claim in a wrongful death lawsuit against the facility, that Eric was grossly misdiagnosed.

The case never made it to trial and was settled out of court, and one of the provisions of the settlement bars any of the parties from discussing it. But according to court documents, Eric was evaluated on August 6 by Monadnock Family Services psychologist Richard Slammon, who took the following notes: “Eric reports suicidal ideation that has been fairly chronic for close to one-and-a-half years. The ideation has included some degree of planning but no intent. Eric adamantly denies that he would ever or has ever acted on his suicidal feelings, primarily because he is aware of the impact that such an act would have on his family, whom he reports to love very much. Eric’s risk for causing harm to himself is considered to be moderate, but not acutely at risk at present.”

Slammon then referred Eric to psychiatrist Richard Stein, who met with Eric three times – August 12, August 31 and September 4. According to court documents, Dr. Stein prescribed Eric several drugs without his parents’ consent – Prozac and Paxil, the powerful anti-anxiety medications Klonopin and Lorazepam, and the sleep-inducing drug Trazadone.

It’s possible, according to psychologists and psychiatrists told of Eric’s condition and interviewed for this story, that Eric’s most probably diagnosis was missed: Manic depression (also called bipolar disorder). David certainly thinks so. “After reading about bipolar disorder, I have no doubt that’s what Eric suffered from,” David says. “But at the time, none of us saw it. He was always up. He didn’t look depressed.”

But, looking back, David and Eric’s friends can see that Eric exhibited many of the characteristics of a “manic” person: He didn’t sleep much. He exhibited reckless and impulsive behavior (drugs and alcohol). He could be grandiose and over-confident. He often was over-talkative and had racing speech. He was hyperactive and had trouble concentrating.

But what about depression? Eric never seemed down or depressed. That’s one of the reasons bi-polar disorder is so hard to catch. Many manic-depressives – particularly those who are perfectionists – keep their depressive episodes out of sight. Still, there were some symptoms Eric couldn’t hide in the months before his death. He lost weight, and he slept odd hours. He would rarely sleep at night and he would collapse of fatigue at some point during the day. “But again,” David says, “so do a lot of teenagers. And his weight loss I attributed to the fact that he wasn’t working out as much.”

If Eric was bipolar, then giving him Klonopin and Larazepam – two antidepressants – without a mood stabilizer is a dangerous combination, according to several psychiatrists interviewed for this story. “It can lead to what’s called a mixed state, where the person is both depressed and hyper manic at the same time,” says Dr. Richard Prather, a psychiatrist and medical director at the Sante Center for Healing. “The hyper mania gives the person the energy to actually follow through on a suicide attempt.”

Klonopin and Lorazepam also are not to be used with alcohol, but Eric was drinking heavily in the months before his death. Eric told Dr. Stein that he often drank glasses of hard liquor alone after school. According to court documents summarizing the expected expert witness testimony of psychiatrist Allen Shwartzberg, of the Psychiatric Institute of Washington, Dr. Stein’s notes “clearly indicate a severe and life-threatening deterioration of Eric’s condition. Dr. Stein completely failed to recognize and/or treat this condition…Dr. Stein’s notes document self-destructive behavior of drinking glasses of undiluted liquor, mixing alcohol with drugs against the doctor’s advice, and over-medicating himself with the prescribed medication…The drug regimen prescribed as inappropriate, particularly in light of Eric’s abuse of the drugs and his use of alcohol.”

David and Rose say they didn’t know the extent of Eric’s drinking. They also knew little about what Eric was talking about in therapy. “After that first visit, Eric just shut me out,” recalls Rose. “I didn’t know anything. Eric didn’t want to talk about it. (Monadnock Family Services) didn’t tell me anything about any drugs. I just thought he was going to see a therapist to talk about whatever he was feeling. I just thought a therapist was someone you go to see for a few sessions, and then you feel better.

Nobody realized that Eric was a perfect candidate for suicide: More than 90 % of teen suicide victims have a mental disorder, such as depression, and/or a history of alcohol or drug abuse. Eric had both. Still, Eric didn’t exhibit many of the other characteristics of a depressed or suicidal teenager. He didn’t seem sad. He didn’t have visible mood swings. He didn’t express self-hatred, harass others, or withdraw noticeably from friends and family. He didn’t talk about death.

When Rose told David in mid-August about what Eric had told her on Hampton Beach, David was stunned. “The whole thing was just so off the wall,” recalls David. “I spoke to Eric for about 30 minutes that night, and he blew the whole thing off. He said he was a little bit stressed, but now he was fine. I just accepted what he said on face value. I didn’t know about any drugs. He was still always smiling.”

In the week before Eric died, Monadnock soccer coach, Chana Robbins, didn’t see Eric’s smile as often as he would have liked. In fact, Robbins and Eric were frequently in disagreement, with coach wanting more hustle form his best players, and player wanting less lip from his vocal coach. On Sept. 27, 1999, four days before his death, Eric brought his girlfriend, Denene Groat, on the team bus with him to an away game. Eric played poorly, and Robbins, furious when Eric drew a yellow card for roughly tripping an opposing player in the open field, benched him. On the bus trip home, Eric rested his head in Groat’s lap. “I’m so depressed,” he told her. Groat assumed he was talking about soccer.

Three days later, Eric quit the team after Robbins took away Eric’s captain status for two games. The next day, Eric left school early with no explanation. Worried, Groat drove to the condo Eric then shared with his brother and father. David was at work, Greg was at school, and the door to Eric’s room was locked. She walked downstairs, where she found a single-page, hand-written note signed by Eric: I can no longer watch depression win me over and destroy my opportunities…Soccer plays no part in this…I am sorry you cannot fully comprehend my situation for just one second…I was not chemically meant for this world.

Depression? Chemically meant for this world? Groat didn’t understand a word of it. She grabbed a coat hanger from Greg’s room and unlocked Eric’s door, using the technique Eric – prone to doing absent-minded things, like locking himself out of his room – had taught her. When Groat opened the door, she found Eric dead on the floor, his father’s .44 Ruger by his head. (When he died, Eric’s blood-alcohol level was at 0.41 percent.)

At Monadnock, the soccer team was midway through practice when David came sprinting down the hill and called Greg off the field. “By the way David came running, we knew something had happened,” says Josh Tong, then the team’s senior goalie and a friend of Greg’s. “We thought that maybe Eric had gotten into a car accident. They rushed us all over to the side of the field, and you could see David and Greg talking. Then Greg just dropped to his knees.”

To everyone who knew him, Greg was a different person after Eric died. “Part of me knew on some level that Greg would probably end up killing himself,” says Josh Tong, a good friend of Greg’s. “I had never seen someone so sad and angry.”

Three weeks after Eric’s death, Greg told a friend, Lindsey Jernberg, that he was going to overdose on pills. “Greg and I had talked every night since Eric’s death, usually about Eric,” recalls Jernberg, then a popular Monadnock senior who played softball, field hockey and basketball. “So I called him about 8 the night of his last soccer game and he wasn’t himself. He wasn’t talking at all. I knew something was wrong. I kept hounding him, asking him what was wrong. Finally, he just lost it. He started yelling at me and swearing at me. He said, ‘I can’t believe you fucking called me! You ruined all my fucking plans! I had everything fucking planned!'”

Greg was hospitalized for ten days. When he returned home, he began seeing a therapist and a psychiatrist, who prescribed him Paxil. Greg told friends he got little out of his therapy sessions and didn’t like taking his medication. “He joked a lot that he couldn’t get an erection on Paxil,” says friend and then Monadnock senior Tim Wilder.

Much of Greg’s anger (and friends say he had a lot of it after Eric’s death) was aimed at his mother, whom he never forgave for not telling him that Eric was depressed. Still, not every day was bad, and Greg’s two closest male friends last year – Jordan Self, then 14, and Casey Gallagher, then 16 – said they never consciously feared that Greg would commit suicide. (Greg told them several times that he wouldn’t.)

The three boys spent most of their free time joking around and bonding over their difficulties with girls, which were endless. For whatever reason, Greg – who had a body that turned heads – was rejected by several girls he had crushes on. “He would always say, ‘Girls don’t go for nice, romantic guys like me,'” says Greg’s friend, Christen Arrow. “And he was right. In high school, most girls go for the cocky jerks. But I think a lot of people also got weirded out by Greg toward the end. He was a lot different than he was before.”

For one thing, he started to look eerily like his brother. He wore Eric’s soccer uniform during games, sometimes wore Eric’s clothes to school, and grew his hair long like Eric’s. “It spooked people out,” says friend Kris Kesney. Greg also became obsessed with studying suicide: He read books about suicide, depression and bi-polar disorder and wrote a 13-page paper for English class entitled, “The Social Enigma of Suicide.”

“Even with all of the opportunities to identify and prevent suicide,” Greg wrote, “teenagers still complete suicides and throw their friends and family into turmoil and an endless void of ‘What ifs?'”

School officials say they carefully considered letting Greg play the role of Conrad. “Paul and Greg’s therapist felt strongly that the play was going to be therapeutic,” says Principal Daniel Stockwell. “His parents had been consulted. In my mind, I’m thinking, “Greg’s out there, he’s able to express himself, don’t take that away from him.’ Keep in mind that the ending of the play is the surviving boy coming out mentally strong. This could have been a very positive story – if it had stayed to script.”

There were countless signs that it wouldn’t: Greg was hospitalized a second time by his therapist, who considered him dangerously suicidal. A week before his death, Greg cut his wrists – a school guidance counselor confronted Greg and called his therapist, but David and Rose say they were never told. This was typical of the misinformation and silence surrounding Greg’s behavior: David and Rose knew very little about what Greg was doing or thinking.

“When I saw the marks on his wrists and confronted Greg,” recalls David, “he said he had gotten cut at work. We didn’t find the truth out until after he died.” Greg later told Katharine DePew that he was living for the play, and that once it was over, he would kill himself. Again, no one told David and Rose. “Everyone was so worried about the week after the play,” says DePew. “No one expected he would do it before.”

Greg also told several friends that he didn’t want to live to be older than his brother. True to his word, he lived one week less.

Like news of Eric’s suicide 14 months before, Greg’s suicide spread through Swanzey in a matter of hours. “People couldn’t believe it,” says the mother of one Monadnock student. “And people were so angry. Everyone wanted to find something to blame.”

There were two main targets. The first was “Ordinary People.” Angry students and parents – most of whom didn’t know Greg was playing the role until after he died – wanted to know why Greg, a suicidal teenager, was playing a suicidal teenager in the school play. “The first few days of school after Greg died, I talked to so many people who said, ‘I can’t believe they did that play! They shouldn’t have done the play!'” recalls Christen Arrow, who played the role of Conrad’s mother. “I couldn’t believe people were blaming his death on that.”

But people did, and David added to the anti-play sentiment when he talked to the Boston Globe two days after Greg’s death. “When I heard about the play, I thought it was a sick joke,” he told the Globe. “I couldn’t believe it. I blame myself for not stopping it outright.” David says he regrets making that statement. “The reporter talked to me as I was going to my son’s funeral,” David says now. “I don’t blame the play for what happened.”

Neither do most of Greg’s close friends, many of whom angrily defend Greg’s role in “Ordinary People.” “I am so sick and tired of all these people who didn’t even know Greg saying that the play killed him,” says Katherine DePew. “The fact is, if they had cancelled the play or told Greg he couldn’t act in it, he would have killed himself the next day.”

To hear most of Greg’s friends tell it, there was little doubt that Greg would kill himself. But they express anger and astonishment that David kept his gun in the house after Eric’s death, making a suicide easier to complete. (Teens are much more likely to kill themselves when they have access to guns.) While David insists there was no ammunition in the house and that the gun – which he bought in 1988 as a security device, and occasionally used for target shooting – was locked in the attic and had a trigger-lock, it’s an explanation that Greg’s friends say falls short.

“Who the fuck keeps a gun in the house after your first kid kills himself with it?” says a close friend of Eric and Greg’s. “When I heard the way Greg died, I was like, ‘Are you kidding me?’ Why would David do that? Why would he even take that chance? What purpose did it serve? It’s not like the gun is a memento. I guess my question is, does he still have it?”

David says he doesn’t. “With 20/20 hindsight, I would have removed the gun, but I am quite sure that the result would have been the same,” he says. “Greg stressed many times how easy it was to commit suicide, and he was an expert on various methods. Greg believed in personal responsibility and liked the saying, “Blame the finger, not the trigger.’ I understand that people want to blame one thing so they can say to themselves, ‘This can’t happen in my life because I don’t own a gun, or because my kid isn’t in a play about suicide.’ The truth is, I’m not sure anyone could have stopped what happened. Eric died because he didn’t think he could live with his illness, which none of us knew about. And Greg? Greg died because he couldn’t live without his older brother.”

The deaths of Eric and Greg Kochman left several of their friends suicidal. Three years later, the brothers’ deaths still invade their friends’ dreams. Kris Kesney has a recurring dream involving Eric: It’s a cold, dark, quiet winter night, and he and friend Travis Smith are relaxing in front of an old ski cabin. Slowly, a police car pulls up. “Shit, what did we do now?” Kesney thinks to himself. Nothing, it turns out. Out of the cruiser’s driver seat steps Eric Kochman, beer in hand and grin on face. “I can’t stay long,” Eric says, lighting a cigarette.

The boys drink a beer together, after which Eric says he better be going. “I feel okay now,” Eric tells them. “I’m all right.” As Eric walks back to the cruiser, he stops, pivots, and look at Kesney. “Kris, you better do your goddam schoolwork,” Eric says. “You be well with yourself. I don’t want to see you fail.” With a beer in one hand and a cigarette in the other, Eric steps in the car’s driver’s seat. He sits down, shuts the door, smiles, and drives into the black night.

Greg Kochman also had a dream after Eric died. Greg’s dream, according to a suicide note he wrote before he was hospitalized, goes like this: In my dream, I had killed myself but had come back to Earth as an observer. Eric and I were reunited and it was the happiest dream I have ever had. We talked with people, talked to each other about things we had done, and my death seemed almost like an unreal inside joke between the two of us.

©2004 Benoit Denizet-Lewis

Benoit Denizet-Lewis, a freelance writer living in New York City, is researching teenage behavior during his fellowship year.