HANFORD, Washington — The mulberries happened to be ripe. They caught the eye of a hell-raising physicist by the name of Norm Buske. He picked a quart and rushed home to make what turned out to be high-anxiety jam.

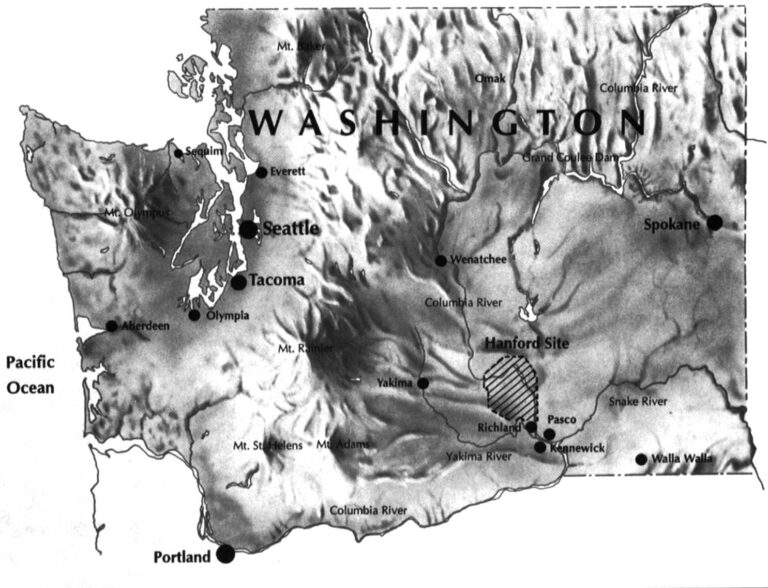

The berries grew here along the banks of the Columbia River, where it arcs across a sagebrush desert in southeast Washington State. The river borders the Hanford Site, America’s largest and leakiest repository of nuclear waste. After Buske made his jam, which was radioactive, he mailed it to the governor of the state of Washington and to the secretary of energy in 1990.

So it was that two jars of ruby-red preserves gave birth to the mulberry syndrome.

Within hours, emergency mitigation began. Hanford workers, wearing blazing white radiation suits and wielding chain-saws, rushed to the west bank of the Columbia. They mowed down every mulberry bush in sight. They stuffed severed branches, fallen leaves and bruised berries into concrete coffins.

As part of an “Expedited Response Action,” the government hatched several multi-million-dollar schemes to prevent hot jam from again reaching the desks of higher-ups. One plan under high-level review would insulate the west bank of the Columbia from radiation by quick-freezing dirt.

Norm Buske’s jam points to the high costs, low comedy and insidious health risks that are daily fare at Hanford, where the federal government is struggling — and, by most measures, failing — to control the most expensive environmental cleanup project in American history.

Until the summer of 1993, conventional scientific wisdom had set the price tag for the 30-year cleanup at an astronomical $50 billion. But that figure is too low by a factor of six, according to a new University of Tennessee estimate that federal officials say is realistic.

Three hundred billion dollars, for purposes of perspective, is three times the total cuts in federal defense spending planned through 1998. That much money over the next five years would employ 200,000 people in the armed services and 1.9 million workers in the defense industry. Yet, even $300 billion does not count the demolition and removal of radiation-contaminated buildings from the Hanford site.

Hanford is where the U.S. government chose to produce the bulk of its weapon-grade plutonium, for the atomic bombs that ended World War II and for the hydrogen bombs that sustained the Cold War. In their top-secret rush to produce fuel for weapons of mass destruction, technicians at the 560-square-mile federal site dumped at least 440 billion gallons of contaminated water into the sandy dirt. Another 61 million gallons of waste were pumped into 177 underground tanks, some of them as large as the Capitol dome and at least 68 of which leak.

An unknown percentage of this waste, poisoned with radioactive elements, toxic chemicals or both, has seeped into the ground water beneath Hanford. Plumes of the stuff have found their way into the Columbia River, the great river of the West. The Columbia is the primary source of hydroelectric power and irrigation for nine million people in the Pacific Northwest. About a third of U.S. wheat exports move on the river. Hundreds of thousands of people get their drinking water from the Columbia. They also swim in it, wind-surf on it, fish out of it, and pay top dollar to build houses with views of it.

So far, to the immense relief of the Department of Energy, the huge flow of America’s second largest river has managed to dilute and detoxify seepage from Hanford. Down-stream health risks are not considered significant. Yet state health authorities are nervous.

“Our concern is that the enormous amount of contamination introduced in the soil at Hanford will at some point find its way into the river and cause us trouble,” said Ralph Patt, a hydrogeologist who monitors Hanford for the Oregon Water Resources Department. The Columbia reaches Oregon about 40 miles downstream from Hanford.

Patt said the U.S. Department of Energy has a responsibility either to prove that dangerous concentrations of waste will never reach the river or to act quickly to sponge up percolating poisons.

The Hanford cleanup is supposed to do just that, but federal watchdog agencies and some members of Congress say they are disgusted by how little actual cleanup action is underway here.

“A toxic abyss of unimagined depths,” Sen. Mark Hatfield, a Republican from Oregon, grumbled this summer at a hearing on Hanford held by the Senate Energy and Natural Resources Committee. Committee chairman Sen. J. Bennett Johnston, a Democrat from Louisiana, said “the frightening thing is nothing has been cleaned up. There is paper pushing, there are clouds of dirt out there, but nothing is being accomplished.”

The record of Hanford’s commitment to safety is not inspiring. In the 1940s and 50s, more than 500,000 curies of radioactive iodine 131 were released without warning into the atmosphere, contaminating a broad downwind swath of Eastern Washington. The size of the release exceeded the 1979 Three Mile Island accident by a factor of at least 20,000. After Three Mile Island, local residents were evacuated and milk impounded. Those who lived downwind of Hanford were not even aware of their exposure until decades after it occurred. They did not receive official word of the cancer-causing potential of the releases until 1990. Federal studies are underway to assess the validity of what “downwinders” claim has been an alarming pattern of cancer, thyroid disease and other diseases in their families.

An unknown percentage of this waste, poisoned with radioactive elements, toxic chemicals or both, has seeped into the ground water beneath Hanford. Plumes of the stuff have found their way into the Columbia River, the great river of the West. The Columbia is the primary source of hydroelectric power and irrigation for nine million people in the Pacific Northwest. About a third of U.S. wheat exports move on the river. Hundreds of thousands of people get their drinking water from the Columbia. They also swim in it, wind-surf on it, fish out of it, and pay top dollar to build houses with views of it.

So far, to the immense relief of the Department of Energy, the huge flow of America’s second largest river has managed to dilute and detoxify seepage from Hanford. Down-stream health risks are not considered significant. Yet state health authorities are nervous.

“Our concern is that the enormous amount of contamination introduced in the soil at Hanford will at some point find its way into the river and cause us trouble,” said Ralph Patt, a hydrogeologist who monitors Hanford for the Oregon Water Resources Department. The Columbia reaches Oregon about 40 miles downstream from Hanford.

Patt said the U.S. Department of Energy has a responsibility either to prove that dangerous concentrations of waste will never reach the river or to act quickly to sponge up percolating poisons.

The Hanford cleanup is supposed to do just that, but federal watchdog agencies and some members of Congress say they are disgusted by how little actual cleanup action is underway here.

“A toxic abyss of unimagined depths,” Sen. Mark Hatfield, a Republican from Oregon, grumbled this summer at a hearing on Hanford held by the Senate Energy and Natural Resources Committee. Committee chairman Sen. J. Bennett Johnston, a Democrat from Louisiana, said “the frightening thing is nothing has been cleaned up. There is paper pushing, there are clouds of dirt out there, but nothing is being accomplished.”

The record of Hanford’s commitment to safety is not inspiring. In the 1940s and 50s, more than 500,000 curies of radioactive iodine 131 were released without warning into the atmosphere, contaminating a broad downwind swath of Eastern Washington. The size of the release exceeded the 1979 Three Mile Island accident by a factor of at least 20,000. After Three Mile Island, local residents were evacuated and milk impounded. Those who lived downwind of Hanford were not even aware of their exposure until decades after it occurred. They did not receive official word of the cancer-causing potential of the releases until 1990. Federal studies are underway to assess the validity of what “downwinders” claim has been an alarming pattern of cancer, thyroid disease and other diseases in their families.

By the standards of hydrogen-burping tanks filled with millions upon millions of mysteriously explosive nuclear waste, Hanford’s mulberries are small potatoes.

Even the worst of the berries, before the rampage of technicians with chain-saws, were only marginally radioactive. Norm Buske admits that he would have had to eat an entire jar of mulberry jam every day for a year before a health risk emerged. But in environmental politics, where nuclear paranoia is a given and distrust of government runs deep, media perception can outweigh science.

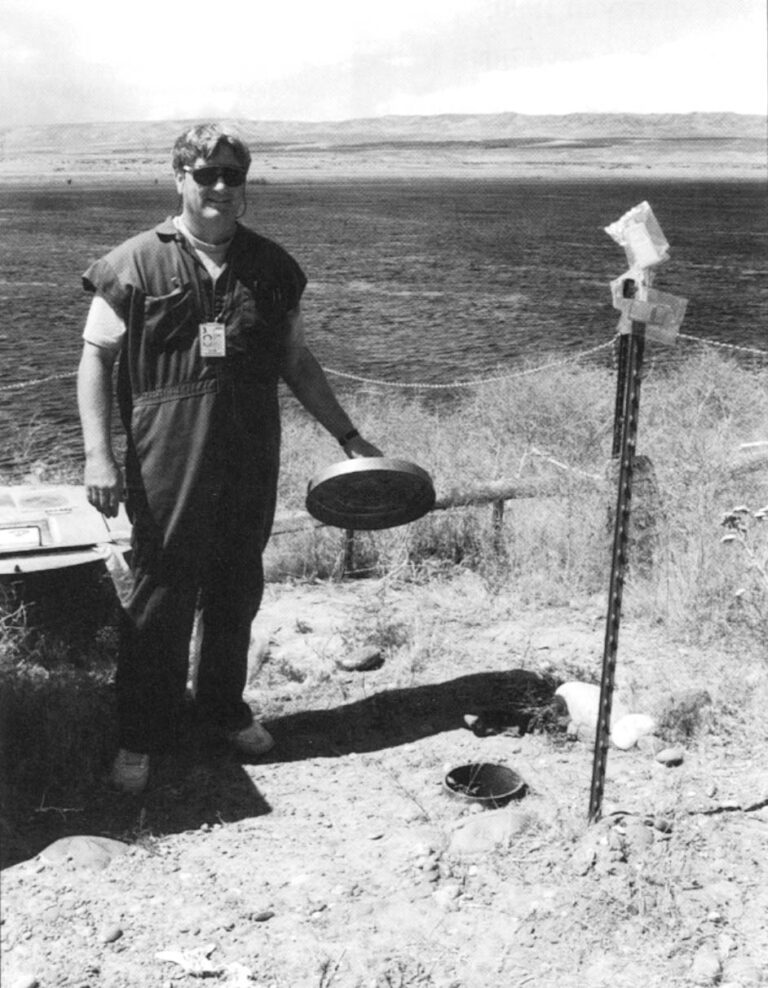

Buske and his then-wife, Linda Josephson, were searching for a suitable media perception when they paddled their rubber boat three years ago into the shallows on the Hanford side of the Columbia. Buske, 49, a physicist and oceanographer, has experience in a generating a good media perception. The Washington State resident was chief scientist on the 1989 voyage of the Rainbow Warrior, a Green Peace ship that made headlines around the world when it challenged French nuclear testing in the South Pacific.

“At Hanford the government position was there is no problem along the Columbia. The government said there is nothing to look at. What we intended to do was to see if there was anything that might be interesting,” recalls Buske, who was working for Green Peace in 1990 when he spotted the berries.

“We had no idea the mulberries were there. They were ripe, and the river was high. To pick them, we didn’t even have to get out of our boat.”

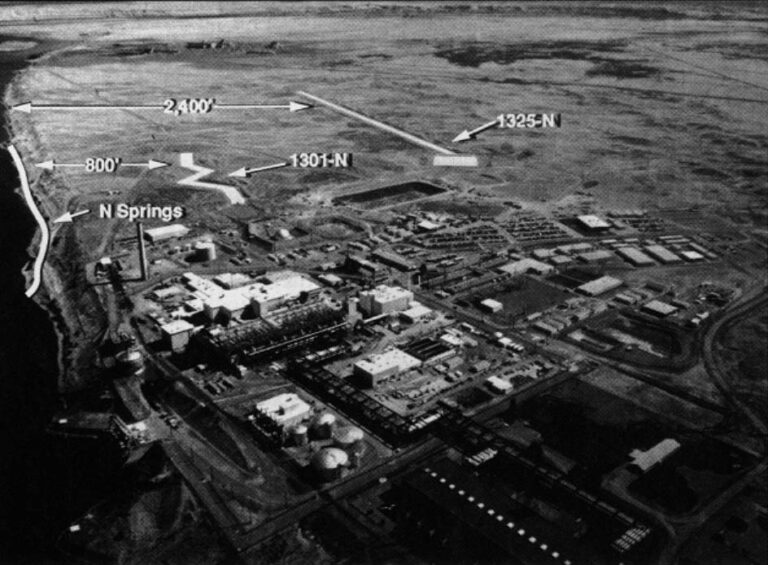

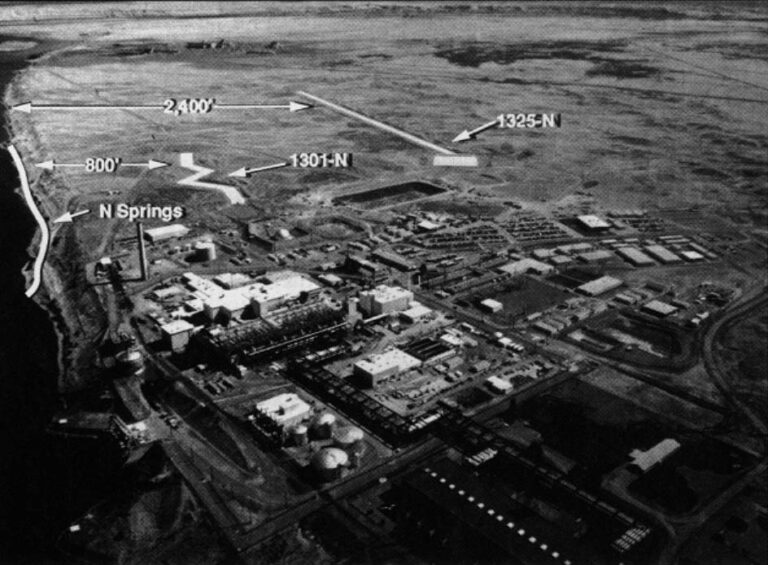

The roots of the mulberry bushes drew moisture from an underground spring that lies in the shadow of a hulking concrete structure called N Reactor. It once was the U.S. government’s premier source of plutonium for nuclear weapons.

“N Springs,” as Hanford technicians call it, flows beneath the reactor’s two waste-water trenches. Then it seeps out along the river bank and drips into the Columbia.

During the more than 20 years that N Reactor produced plutonium, a billion gallons a year of contaminated water were pumped into the trenches. The oldest and most heavily contaminated of the trenches is less than the length of a football field from the river.

After N Springs runs underneath these poisoned trenches and before it meets the big river, it carries about 900 times the safe drinking water concentration for strontium 90. A by-product of plutonium production, strontium 90 is a highly carcinogenic radioactive element with a penchant for seeking out and lodging in the bones of animals and human beings.

Battelle Northwest Laboratories, the main environmental contractor at Hanford, had long been aware of the radioactive bite in N Springs. To mitigate it, Battelle suspended waste-water dumping in the trench nearest the river in the early 1980s. Like the entire Hanford Site, N Springs and nearby vegetation were (and still are) off-limits to the public. The area is posted with no- trespassing signs that advertise the radioactive threat.

But the Columbia, as it passes Hanford, has been open for recreational boating since the 1980s. There is nothing illegal about paddling around on the Hanford side of the river, as long as you stay in your boat.

Buske was doing just that, when the unexpectedly juicy mulberries insinuated themselves into his antinuclear imagination. After picking the berries, making two jars of jam and mailing them to the governor and the secretary of energy, Buske took time to alert the media.

“This mulberry jam is a token of the future hazard of unidentified, uncontained and unmanaged radioactivity at Hanford,” Buske wrote in a letter.

Within a few days, alarmed consumers swamped the Washington State Department of Health. They wanted to know about the safety of the state’s celebrated apples and peaches. Agribusiness got angry, politicians demanded action, and Hanford technicians started spending money in search of solutions.

After the chain-saw massacre, bits and pieces of mulberry bushes were collected in 20 four-by-eight-concrete burial boxes. Those specialized coffins are to be transported to Oak Ridge, Tennessee, where there will be burned in the nation’s only government-certified incinerator for low-level radioactive materials. The ashes of the mulberry bushes will then be brought back to Hanford for burial. The price tag for cutting, shipping, burning, reshipping, and burying the mulberry bushes, according to Westinghouse officials, will approach a half million dollars.

The cost of stanching the radioactive dribbles that nourished the mulberries will be much, much higher.

N Springs has jumped to the head of the queue for the 1,100 separate sites at Hanford in need of cleanup. Eventually, the underground plume of radioactive material near N Reactor may be dug up and moved back from the river. In the short-term, there are high-tech proposals to block the offending water.

The ice-wall solution, which Westinghouse says would cost $15 million, involves sticking a series of pipes in the ground, pumping in refrigerant and freezing the soil into a solid wall. Other schemes include excavating a trench along the river and replacing dirt with waterproof clay ($34 million), injecting cement in the ground ($20 million) or making a wall of water that would make N Springs flow away from the Columbia ($20 million, plus maintenance of $30 million a year).

“It is not cheap, it will be an expensive action,” says Ralph Johnson, a nuclear engineer who manages the Environmental Remedial Action Group at Hanford, which focuses on urgent cleanup needs. He said work at N Springs will begin this year.

Meanwhile, no one is happy about N Springs. Although its impact on Columbia River water quality is next to nil, it is a highly visible and, for Hanford officials, highly irritating symbol of environmental negligence.

At lower levels, longtime Hanford employees complain about wasting money on a minor problem that will cure itself with time, as the half-life of radioactive pollution runs out. These engineers cringe at the mention of concrete coffins full of marginally toxic mulberry remains.

“Buske and his tactics have probably extracted a half million dollars out of taxpayers,” says Jerry Erickson, a retired engineer who spent most of his career at N Reactor and is now a consultant in its cleanup. “These environmentalists feel proud of themselves because they have done something to big bad government. Well, everybody has to pay.”

Buske, himself, is outraged that the Department of Energy and its contractors murdered the mulberries.

“After the jam, they were really freaky,” Buske said. “My feeling is they should have left the mulberries alone. Chain-sawing them merely killed the messenger.”

©1994 Blaine Harden

Blaine Harden, on leave from The Washington Post, is examining the Columbia River and its environs.