On a Saturday morning late in December, hundreds of black parents, including many professionals, and their children, attended a cultural event at the American Museum of Natural History in Manhattan. The occasion was a Kwanzaa festival, an African-American holiday that celebrates the richness of black culture with the lighting of candles, poetry and feasting.

To the beat of a Stevie Wonder tune, three brown face puppets performed a skit depicting a black teenager arrested on suspicion of robbery after innocently walking through a white neighborhood. Eventually, he was sentenced to prison.

In the back row of the auditorium, an adolescent giggled. His mother, dressed in a costly Burberry raincoat, glared at him.

“Better not laugh,” she said. “That could happen to you.”

Her message was understood by many nearby. It carried a warning often repeated by black parents, cautioning that success cannot insulate one from the complications of being black.

The youth fell silent and looked perplexed. Ironically, when he and his mother departed, home was in a predominately white neighborhood, if they were like many of the blacks in attendance. Pockets of black professionals have existed in the United States for more than one hundred years. But today, as a segment of the first generation not born into segregation, thousands of black middle class children live and learn in neighborhoods where only decades ago their ancestors worked as domestics.

Sometimes these privileged offspring are called BAPs, black American princes or princesses, for they stand in such sharp relief to the black underclass and they seem to have it all. But there is little cause for celebration.

Many are the sons and daughters of black Baby Boomers who came of age during America’s Civil Rights Movement. While the adults’ afros and dashikis may have gone the way of mini-skirts, their insistence on maintaining cultural roots has not. This can be emotionally conflicting for the children.

On one hand, they are offered opportunities made possible by victories of the 1960s and 1970s, such as enrollment in prestigious schools and comfortable homes in upscale neighborhoods–often in predominately white environments. On the other hand, these children are encouraged to think of themselves as part of a universal black family, a sweeping throng of Africans, islanders, and black Americans, both the achievers and the disadvantaged.

But given the reality of racial problems in this country today, those dual expectations suspend these youngsters between two worlds that are engaged in a cold war. They are immediately identified with one world because of their skin. In the other world, they are encouraged to mix but not to become immersed.

The split cultural personalities these children are manifesting might sound unhealthy, says San Francisco therapist Brenda Wade. But she said middle class blacks have been handling similar situations for years without sustaining emotional damage. “These kids learn to be more flexible culturally and are able to deal with a broad range of people and curricula,” she said. “But they also develop a healthy paranoia about whites. That may be necessary if, as adults, they are going to survive racist situations that are potentially dangerous.”

From Harlem to Queens

Most young people experience emotional conflicts, but this group has an additional burden. Their confidence in the future is tempered by reports of the past and dulled by a racial climate increasingly less tolerant of differences. Their plight makes telling commentary about American society. For them, seemingly ordinary circumstances can be unsettling, as was the case for four-year-old Masud Freeman of New York.

When it came to child rearing, his mother, Karen Freeman, had decided years before his birth where he was going to live. She is a 38-year-old attorney, who wanted to raise her son in a neighborhood atmosphere different from the one she had known in her youth. In the 1960s, when Freeman was a girl, her family moved from Harlem to Queens. Freeman views it as a mistake. She is still haunted by the greeting she received from some neighbors in the then all-white Cambria Heights neighborhood.

“They threw rocks, broke into the house, scrawled on the walls, chased me down the street and made bomb threats,” said Freeman.

After finishing law school and building a successful civil rights practice, Freeman headed for Harlem to a middle class enclave.

“My mother can’t understand why I want to live here,” said Freeman. “Well, I have a very negative attitude about integrated neighborhoods, and besides, I like living around black people. Also, I wanted Masud to know that because of racism, a lot of black folks may be poor in this country, but they still have much to offer the world culturally and historically.”

Freeman said she is teaching Masud about his heritage by pointing out global events concerning blacks, and taking him to South African demonstrations. “I want him to feel a sense of struggle, because black people have had to struggle to survive.”

Unfortunately, Freeman said that on the streets of Harlem they often pass through scenes that confuse the boy.

“We see blacks in wasted lives,” she said.

So despite her efforts, she said that recently when a black friend knocked on the door, Masud hid behind her skirts and screamed, “Mommy, don’t let that black man into our house.”

Lately, Masud has been saying he wants to be white, like Nicholas, his best friend at nursery school. Freeman discussed this with a counselor. “She told me not to worry because most black kids in predominantly white schools do that,” said Freeman. “Well, that may be typical but it’s not normal. All of this puts parents in a real dilemma. Our children will have to develop strengths to survive all of this.”

Seventeen-year-old Nichele Guiton of Washington, DC began her life much like Masud. “When I was a kid it didn’t matter what my mother told me,” said Guiton. “I saw myself as being white like my classmates.”

Guiton, the daughter of a federal commissioner and business entrepreneur, is a senior at Georgetown Day High School who seems to have survived it quite well. She is a leader on her volleyball team, feels comfortable around both whites and blacks, and is hoping to attend the University of Virginia in September to major in architecture.

Her relationship with other blacks has not always been smooth. “When I visited my cousins, their friends teased me about acting and sounding white,” said Guiton.

Years later, at a program for black high school students, she had similar problems. “It was the worst time of my life. Some of the kids threatened me and wanted to beat me up,” said Guiton.

Now at Georgetown, an elite prep school with a small minority enrollment, she said she sees some racial hostility. “In the lounge, the black kids sit on one side, the white kids sit on the other.”

Guiton said many of the black students feel they have to act tough and angry, and the white students react with hostility.

Guiton’s first heart throb was a white boy. He reciprocated and their parents thought the idea charming. But by the time she reached junior high, Guiton experienced what others interviewed have described as a social separation along racial and gender lines. The black boys were viewed as acceptable by white girls, but black girls were socially ignored by whites.

Loreal McDonald, 12, who attends Packer Collegiate Institute in Brooklyn, described the phenomenon. “It was suddenly as if my white friends had been told something.”

McDonald said one white friend, Julia, tried to buck the trend by inviting her to a birthday party at a country club. But McDonald said once there, students she had known for years acted strangely.

“I was the only black person,” said McDonald. “People treated me as if I had come to sweep the floor. Girls kept asking sarcastically if I belonged to the beach club.”

McDonald refuses to be typecast. She said there is a look favored by white girls at her school, and another by blacks. She said she won’t wear the “Esprit look” that some white girls favor, nor will she wear the “black princess” look. She describes this style as “hair in French braids, ski pants with matching sweaters and leather sneakers, gold necklaces and earrings and sheepskin jackets.”

McDonald said she works hard at just being herself. At lunch time, when students split up into groups according to racial lines, she heads for “the mixed table,” where a group of blacks, whites and Asians gather.

McDonald is also defying the social convention that says black kids should take chorus, instead of classical instruments, and that they shun gymnastics. She plays the cello and is a gymnast.

On the evening of the interview, McDonald was spending the night with Jennifer, a white girl who lives in the same high-priced neighborhood. But their friendship has cost Jennifer some invitations, said McDonald. “She is not part of the ‘in’ group at school.”

Straddling the fence is not always an option. Guiton, five years older, felt she had to choose.

At home, in a spacious condominium with a spectacular view of Alexandria, Va., her lifestyle has assumed no particular color. It could be that of any privileged American youth.

On a typical school day she hurriedly made the bed in her cream-toned bedroom which has fabric-covered walls, a stereo, television and telephone. As she reached for her fur-lined leather jacket, 40 teddy bears stared blindly ahead. Then Guiton raced to her Honda coupe. The drive to school takes 30 minutes.

“Me getting a Honda was no big thing at my school. A lot of the kids drive Jaguars and Porsches,” said Guiton.

Her friendships, however, have assumed a definite hue. When it came time for dating, she did not want to always be at home. “Now most of my friends are black,” she said.

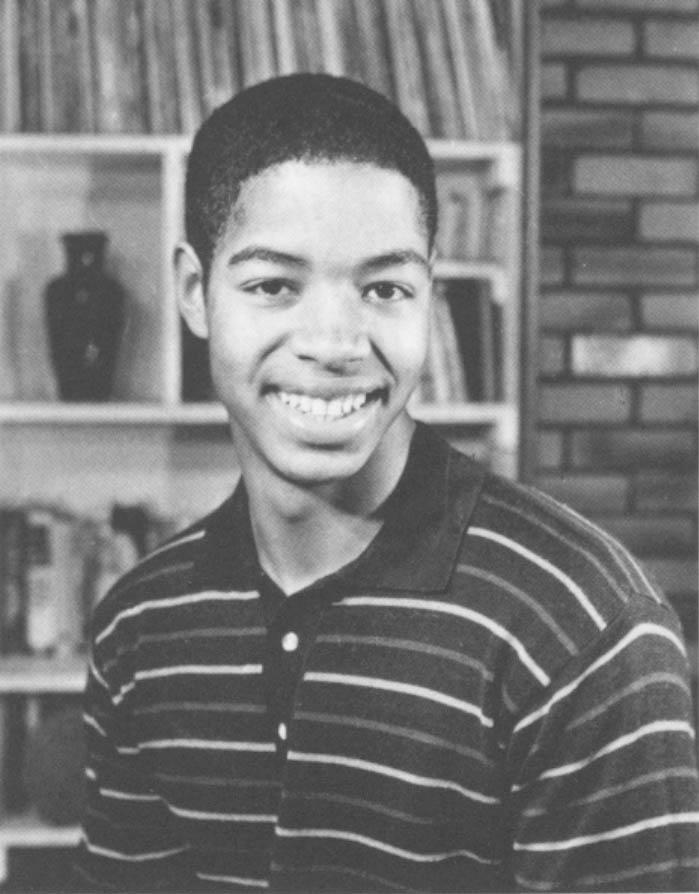

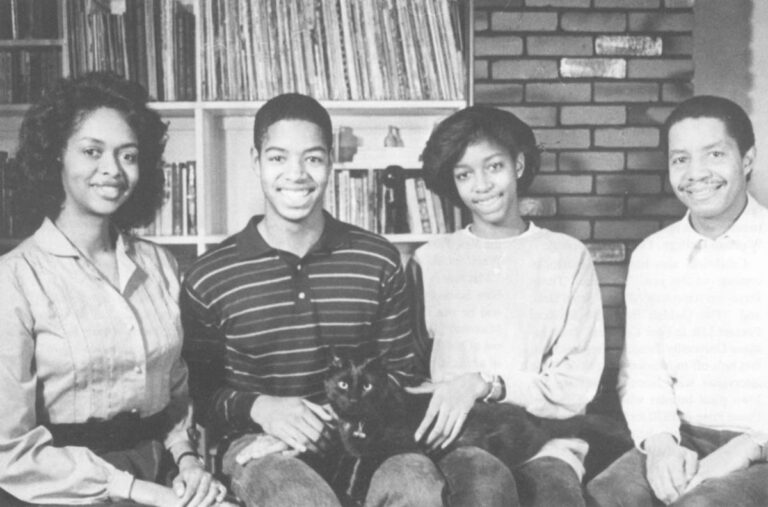

Bert Gibson, 17, did not make such a clear-cut choice. Most of the boys, at the Quaker high school he attends in Manhattan, are white. Like many teenagers, he wanted to fit in.

“When I was 14, one of my white friends used to tease me and call me a ‘spear chucker’ and a ‘chocolate bunny.’ I got angry. But I wondered if he knew I was upset whether he and his friends would still want to be my friends. So I laughed it off,” Gibson said.

He is miffed when his white basketball coach says Gibson doesn’t “sound black.” The implication, of course, is that to sound black, one must speak in dialect.

But once away from school, Gibson feels forced to live out that stereotype, and so does his 14-year-old sister, Erika. They live on Manhattan’s upper west side in a comfortable co-op apartment, with their mother, Nell Gibson, 44, an administrator for the Episcopal Church: and their father, Bert Gibson, 47, a financial planner.

Both children, products of private schools, have two groups of best friends. At school, those friends are white. Weekends, holidays and vacations, they are black.

For Erika, having two groups of friends, and adhering to an unwritten social code, means some subjects are taboo with even best friends. “When I talk about boys, I can’t talk to Katherine (who is white). But I can with Dyan. It’s hard to explain why.”

Although the Gibson children agree that their parents and relatives don’t have an “ethnic” way of talking or walking, they act out the stereotype in fear that they will be shunned by some blacks.

Like others interviewed, the Gibson youngsters said they can assume “black” and “white” mannerisms, depending upon who they’re with.

“When I’m with my black friends I don’t walk straight, my shoulders are down, I kind of bob up and down when I walk, and I dress and speak differently,” said Bert Gibson. “The black kids wear white sneakers and are furious if someone steps on them. The white guys wear Izod shirts and sweaters tied around their shoulders.”

Like chameleons, they move spontaneously between what they perceive as racial mannerisms–a cultural schizophrenia.

A few days earlier, Erika had run into Michelle, a black girl, “I said ‘hey, how ya doin’. Whuts up.”

Moments later, Erika said, she ran into Katherine. “My speech pattern, my whole attitude changed.”

Sometimes the Gibson teens practice dances together that black friends will expect them to know. Bert plays basketball in Harlem and learns the moves up there.

“I won’t do that dance at my school until it catches on with white kids,” said Bert. “Then I pretend I’ve just learned it.”

The Gibson children feel the duplicity is necessary if they want to hide the differences friends notice, but occasionally they forget. “When my white friends see me doing my black walk they tease me,” said Bert.

A few years ago, Nell Gibson gave a party for the black track team Erika belongs to. Mrs. Gibson said one of the members, who is from a financially disadvantaged family, looked around their apartment and whispered, “No wonder Erika talks so funny.”

Raising black children in an upper-echelon world can get so complicated that Mensah Wali, 44, who raised one daughter and then later had two more children, opted for cultural isolation. Today, this Brooklyn based public school administrator and his family live in a black neighborhood and attend Ghanaian religious services. Nanyamka, 8, and Jaja, 9, attend a black nationalist school.

“They have very little contact with the white world,” said Wali. He added that he doesn’t teach his children to hate white people. “We talk about angry, irate whites, like those in Howard Beach, as well as well-meaning ones, like some of the people on my job.”

As for his children learning to exist in the broader American culture, Wali is not concerned. “They’ll learn that anyway.”

None of the other parents I interviewed had chosen lifestyles similar to Wali’s. But all of the others felt certain that a solid grounding in their own culture was necessary for survival as adults functioning in predominantly white worlds. The key, they agreed, is unity among blacks in the face of a society that discriminated along color lines.

Nell Gibson, 44, believes the way she was raised in Jackson Mississippi, “gave me the faith and courage to succeed in life,” and she plans to pass that on. She is the fourth generation of a college-educated family of black activists. She said one of her grandfathers was the first field secretary for the Urban League and a friend of Mary McLeod Bethune, the civil rights leader, educator and adviser to presidents.

“I can remember as a girl, sitting with a cup of tea, as she told me what is was like when she was young,” said Mrs. Gibson.

Later, while in college, Gibson took part in the Civil Rights Movement.

Today she teaches her children about black authors and poets, and each year the family hosts a Kwanzaa celebration, inviting black and white friends. Three years ago, the Gibsons, along with parents and grandparents, traveled to Africa.

“I didn’t want our kids growing up thinking Africa was full of savages,” said Gibson. “If I can teach these children the love and spirit and joy of being black they will be able to survive. That’s a basis of operating in this world that no one can topple.”

Gibson’s pro-blackness does not mean anti-white. She said for 30 years she has maintained a close friendship with a woman who is white. And Alice McDonald, Loreal’s mother, who is a public school teacher, said she also has white friends. Both mothers said they would not oppose their children marrying whites. But McDonald admitted that she would be suspicious of a white man’s motives.

For years, her 16-year-old daughter was best friends with a Jewish boy. “They were on the phone forever,” said McDonald.

But when romance crept into the picture, McDonald interfered.

“I told her to be cautious, that he might be planning to get some experience from her and then begin dating white girls,” said McDonald. “I suggested she read a book on Thomas Jefferson and his slave concubine Sally Hemmings.”

She said her daughter followed her advice and recently told her that as a result, she “could never let a white boy kiss her.”

Asked if she was teaching her children racism, McDonald said, “It has been documented that black women have been used and abused. From the days of slavery we were violated. I have a right to teach my daughters to be cautious.” Like McDonald, few parents said they would counsel their children to transfer to predominately black schools.

“They may have to risk getting their feelings hurt sometimes,” said McDonald. “It’s the only way they’ll learn to play the same games as the future leaders of our country. I want my kids to know the language the leaders use, and I want them to have the advantage of having rubbed shoulders with them.”

None of the young people interviewed blamed their parents for the cultural conflicts they feel. Instead, many would agree with one teenager, who said. “Their plans would have worked perfectly if only blacks and whites had learned to really like one another.”

Therapist Wade stresses that all children should be raised with the idea that they are part of the human family.

“Unless you emphasize a solid inner sense of self, it doesn’t matter what group you see yourself belonging to,” she said.

Lawyer Beverly Baker Kelly of Oakland agreed. Her daughters, Kara, 15, and Traci, 18, have lived in Vienna, Paris and Florence. The Kellys chose Oakland as their home base because it offered the girls positive black role models. She, and her husband, Paul, a dermatologist, have worked to bring their children up as citizens of the world.

They began an education for their children that included a predominately black school from working class families.

Her father was active in the NAACP during the 1950s, a time in Mississippi, when such activities could be dangerous. “They are the real backbone of our race,” said Mrs. Kelly. Summers, the girls attended elite private schools in the East, and one summer the family lived in Montgomery, Alabama in former slave quarters. Another summer found them in a Yoga camp in Montreal “interacting with people from around the world,” said Kelly.

Today the girls can speak five languages. Traci is attending a black college, Spellman University in Atlanta, and Kara hopes to go to Brown University in Rhode Island.

Even with these backgrounds, both girls felt social pressure to choose friends along racial lines. Both gravitated toward a black social circle.

All those interviewed expressed a pessimistic view about the future of race relations.

Loreal McDonald said that when her mother went to school and prejudice was more overt, not much was done about it.

“Now things have changed, sort of,” said McDonald. “Today we can all drink from the same water fountain but there are hidden feelings. You can’t change those feelings.”

Bert Gibson said future generations may have to stage a civil rights movement that will benefit all minorities.

Added his sister, “Hoping for racial harmony is like hoping for world peace. I don’t believe it really can happen. It isn’t consistent with human nature. But not achieving it is not the kind of thing you cry over because it’s such a long shot.”

©1987 Brenda Lane

Brenda Lane, a reporter on leave from the Oakland Tribune, concludes her reporting on America’s new Black middle class.