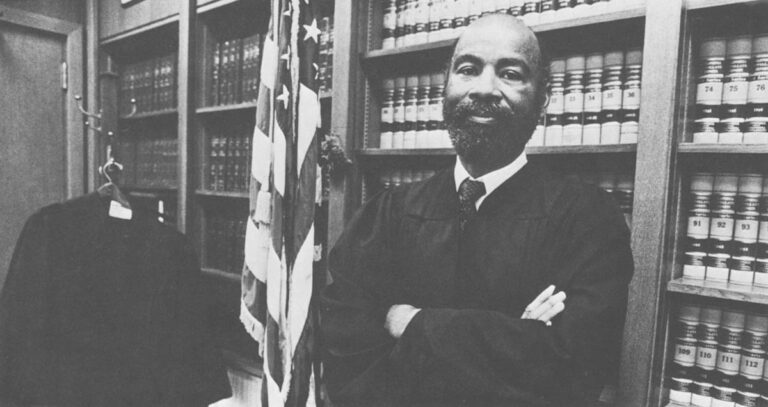

SAN FRANCISCO–The reminders and discomforts linger painfully close to the surface and can be aroused by something as seemingly simple as a case of mistaken identity. On a weekday morning last spring, a white attorney was ushered into Federal Judge Thelton Henderson’s decorous chambers and was greeted by a black man in a dark suit. On a nearby coat rack a judge’s robes hung still and lifeless. Both men took their seats, and a dialogue ensued concerning the case the counselor had traveled from a nearby county to discuss. Soon the attorney checked his watch. A few minutes later, he began drumming his fingers on the polished walnut conference table. The black man continued to talk, ignoring the visitor’s impatience. Seconds went by in single file; more talk and increasing agitation. Finally, the attorney asked, “Where is Judge Henderson?”

For a moment, a look of confusion crossed the black man’s brow and then he realized the attorney’s error.

“He assumed that because I was black I was not the judge,” Henderson later explained.

This was not the last time a white attorney would have difficulty believing that the stately 52-year-old Henderson is a federal judge. It happened again a few months later.

Both incidents lasted only a few minutes. But they were long enough to serve as reminders of the bittersweet irony enveloping America’s emerging black professional class. Career opportunities for this educated and select group continue to open, often in professions that only a few decades ago were closed to blacks.

These new jobs have offered financial benefits that have allowed many to move away from old neighborhoods to exclusive suburbs and areas of cities that held promise of a better quality of life.

But a troubling and enduring problem remains. Some have learned that there are paradoxes to being black and successful in America. They have found it difficult to escape the indignities, racial misunderstandings, and subtle indicators that they are somehow different in an unacceptable way from their white colleagues.

Of 23 black professionals interviewed in the San Francisco metropolitan area, all but two said covert racism prevents them from feeling fully accepted in American society. Their views reflect a far different picture from one widely held that financial and professional success can isolate blacks from racial discrimination.

But this is not merely a Bay Area phenomenon. Another 27 black professionals who live and work in cities throughout the country agreed. Like Henderson, the incidents generally catch them off guard. As professionals they have grown accustomed to being judged by the merit of their work. On the home-front, they have settled into comfortable friendships with their neighbors–black and white–based upon common lifestyles.

For many, their new lifestyles were made possible by changes brought about by the Civil Rights Movement. Before the 1960s, for blacks, class was largely defined by education. It was not unusual, for instance, to find a college educated chemist working as a postal clerk or railroad porter, a job that paid relatively higher salaries than most of those available to minorities.

Today, although their white counterparts remain far ahead, blacks have moved into professional, managerial and technological fields in record numbers–a rise from 8.5 percent of the black employed population in 1964, to 16.7 percent in 1983, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. According to these same reports, there has been a 57 percent increase in the numbers of black professionals since 1973.

U.S. Census figures also indicate that today, 11 percent of blacks age 25 and over have completed college, compared to 4.5 percent in 1970. Another key change occurred when the black suburban population grew from 2.8 million in 1960 to 6.2 million in 1980, according to Census reports.

Bert Johnson, publisher of the San Francisco based magazine B.U.M.P. (Black Upwardly Mobile Professionals) said that while black consumers spend about $200 billion a year in the United States, “the top 20 percent of black incomes make up half of that $200 billion.”

Over the years, the San Francisco Bay Area has become a microcosm of America’s black professional world. It is headquarters for several organizations representing blacks in many professional disciplines, including lawyers, psychiatrists, therapists, social workers, doctors, anthropologists, scientists, college professors and journalists.

They come or remain in the Bay Area for many of the same reasons as white professionals–career advancement, mild weather and relaxed lifestyles. Traditionally, there has also been an added bonus for minorities; it is a polyglot metropolitan area with a reputation for welcoming all ethnic groups. But Judge Henderson and others interviewed, feel it is no more racially tolerant than other cities and states in which they have lived.

Henderson, the son of a domestic and a janitor, grew up in a run-down black neighborhood in Los Angeles, only a few miles from the exclusive homes of Beverly Hills. He moved to northern California in 1951 when he won a football scholarship to the University of California at Berkeley. Drafted into the Army after graduation, he came face to face with overt racism when as an Army softball star, Henderson waited on a cold touring bus while his teammates trooped into “whites only” restaurants throughout Missouri. Today Henderson is on the bench of the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of California.

“Things were clearer then, racially,” said Henderson recently, punctuating his words with an index finger tapped in gavel-like motions. “Today, racism is still pervasive. There is no way a black person can insulate himself from it. I don’t have to have people calling me a “n…..”, my race is a victim of it. And those uncomfortable incidents I encounter are reminders of how unjust racism is.”

While financial planner Barbara Nappi of San Francisco says she is in a happy and sound interracial marriage and has many white friends, she would agree with Henderson.

“It’s just one more issue I have to deal with first,” said Nappi. “My blackness is not something I can talk about later. I have to get it out of the way first, before I can show my expertise. It costs me emotional involvement.”

She believes racism has also cost her at least one big account. Nappi is a second vice president of Shearson/American Express, an investment company. More than 90 percent of her business is conducted over the telephone, with Nappi keeping an eye on the stock reports she scrolls across the screen of her desk top computer. In lightning fast sentences, she makes projections, delivers pronouncements, advises, hedges, rushes out buy and sell orders via clerks, with barely a few breaths in between.

One client, a man whose stock portfolio she handled before coming to Shearson in 1979, invited her out to a celebration drink after she had nudged his profits up to a quarter of a million dollars.

“When he saw me,” recalled Nappi, “he said he didn’t know I was black.”

The meeting was strained, and the next day, Nappi said the man called to say he was pulling his account. Nappi asked him whether the fact that she’d made so much money for him didn’t count. He said it did not, and withdrew his business.

“Six months later he came back and wanted to do business with me again,” Nappi continued. “I refused. There’s just so much I’m willing to take.”

When municipal bond salesman and attorney Dave Alexander, 37, moved to the exclusive suburb of Moraga in 1976, he was prepared to deal with cultural isolation. “My neighbors were extremely friendly,” said Alexander, looking out the window of the office that houses his bustling private practice. From his desk, Alexander has an expansive view of downtown Oakland, which, on a recent Thursday morning, was being washed by heavy rains. “When I lived in Moraga,” Alexander continued, “except for me, every single solitary person that I saw was white.”

Eventually, a few racial incidents drove him out.

On a sunny weekend morning in 1978, Alexander was having a flat fixed on his car and happened to be riding on his bicycle past the garage where his tire was being repaired. At that moment a group of white men standing in front of the garage began shouting and calling him a “n…..”.

“I had never heard it used that way before,” said Alexander. “I turned my bike around and rode past again to make sure I’d heard it correctly, and there it was again. I got off my bike and started across the street to the garage, mad as hell. But there was a traffic light and it gave me time to think. Here I was in Moraga, with a gang of white people calling me “n…..”. I’m a lawyer. Was I really going to fight for this? By the time the light changed I recognized the insanity of it all.”

But this was not an isolated experience. A few months later, while commuting home on the public transit system, an intoxicated white executive asked Alexander in a loud voice, why he wasn’t getting off at the stops where the “rest of the blacks got off.” Alexander said some of the other whites on board were furious. But it gave him some thing to think about. A few months later he moved back to an area of Oakland that is more racially diverse.

Cassandra and William Hastie, both attorneys, live in the wealthy community of Mill Valley in Marin County, in a split-level situated only a few miles from the top of majestic Mt. Tamalpais.

The area’s abundant natural beauty draws thousands of tourists each year. But the Hasties believe it is impossible for blacks to go anywhere–no matter how high up or how exclusive a neighborhood–to escape racism. They say they have experienced many racial incidents in their lives, but Cassandra, 42, feels her recent problem with finding household help is most telling.

When the couple decided they needed a full time live-in maid, to help with their busy schedules, they advertised locally. After what Cassandra calls a few “uncomfortable encounters,” she began telling prospective workers over the telephone that her family is black. When they did finally hire a French woman from Quebec, she worked for awhile, then quit.

“She said she was embarrassed because people thought our daughter might be her child,” said Cassandra.

As in the case of the Hasties, many of the incidents appear not to be intentionally hurtful. More often they stem from ignorance based on stereotypes.

Sheila Stainback, who lived in Los Altos, is now a journalist in New York. She tells of arriving early at a hall to conduct a seminar. When she reached to hang her coat on a nearby rack, a group of white patrons attempted to hand her their wraps, mistaking her for a hat check clerk.

Codolezza Rice, a Stanford University professor who is an expert in Soviet arms policies, was interviewed for two hours by a white reporter. The next day she saw a copy of the story. The opening line read: “She has come a long way up from the ghetto.” The only problem is that Rice was raised in a middle class suburb of Alabama, and has never lived in a ghetto.

The stories abound. Sometimes blacks meet for social occasions and swap details to relieve the pressure.

One man, novelist Ishmael Reed of Oakland, writes about it. His latest book, “Reckless Eyeballin’,” tells a story about a black woman whose screenplay is produced in Los Angeles. But being black gets in the way of a trouble-free project.

According to Reed, “Explaining covert racism to someone white is almost impossible. How do you explain the constant rudeness? Sometimes you start thinking you’re paranoid.”

Apparently there are others who would agree. San Francisco therapist Brenda Wade said she is seeing an increasing number of black professionals who are having a hard time living and working in the emotional cold war they feel caught in.

“The myth is that if they work hard and become a success, they will eventually be judged by their contributions to society,” said Wade. “Then they come to realize that to some whites they will always be “the black” up the hall “the black lawyer,” etc. It’s like walking around in a giant gift box. A lot of people may notice the wrapping but they don’t care what’s inside.”

Wade said the racial incidents can take a toll, causing some blacks to feel inadequate, anxious and angry.

“That’s when I began to see self-sabotage and self destructive behavior. They became ambivalent about their work, forgetting important meetings and showing up late. Usually these people are so highly placed they can’t be fired for small infractions but they lose the respect of their co-workers.”’

Of course, not all black professionals feel this kind of tension. Nadine Watson, 42, of Oakland says she knows racism when she sees it. A native of Kentucky, she can remember Bourbon Street in her hometown of Lexington, where “whites walked on one side and blacks on the other.” As a child, when Watson integrated the local junior high school, whites burned a cross on her lawn.

“But that was then and this is now,” said Watson. “I’m sick of the word racism. It’s like an old record played too long. We’ve used the word so much it’s not effective anymore.”

Watson is married to a physician and lives in the Oakland hills. She said her two daughters have been raised to be color blind. “They date interracially and they have some white friends and we all get along.”

Watson, who is the director of volunteers at a local hospital, said it has been many years since she has encountered any racial hostility or insults. She believes some blacks bring negative attitudes based upon past experiences into their dealings with whites, causing misunderstandings. She hopes eventually to run for office, spreading the message that a new age requires new attitudes “but I don’t think I’d get many black people to vote for me.”

None of the others interviewed agreed with Watson.

And few were willing to put their pasts so completely behind them. In fact, Carol and Chuck Lawrence of San Francisco have made some conscious decisions about their daughter’s future based upon racist experiences in their pasts as well as those they say they encounter today. They hope to isolate Maia, 13, from the kind of social loneliness they have felt as blacks living in a white world.

Carol Lawrence, 43, is an award winning television producer, writer and director. She still has unpleasant memories about the boarding school she attended near Stanton, Pa., where the black and white students were not allowed to room together. “The administration has since invited me to come back for some honors,” said Lawrence, “but I wouldn’t think of it.”

Her husband, Chuck Lawrence, 43, who teaches law at Stanford University, has vivid memories of growing up in Rockland County New York, which at the time was predominantly white and working class. Lawrence’s family was different in many respects.

His paternal great great grandparents had been slaves who eventually bought their freedom and then taught other former slaves how to read. His paternal grandparents had run a black training school in Utica, New York. Lawrence’s father was the chairman of the sociology department at Brooklyn College, his mother a pediatric psychiatrist. Today, one sister, Sarah, is a professor at Harvard and recipient of the prestigious MacArthur award. Another sister, Paula, is a principal of a Quaker school in Delaware. Lawrence himself, won a Regents scholarship, was offered an appointment to West Point and attended Yale Law School.

“We were the guess-who’s-coming-to-dinner-family in our town,” said Lawrence, who has retained the slenderness of his youth.

In high school, during Lawrence’s senior year, he was president of the senior class, Sarah was president of the junior class, and Paula headed the sophomores. Also, Lawrence was captain of the football, track and basketball teams. But apparently, none of that made any difference to the parents of their fellow students.

“I had lots of friends but no one was allowed to date me,” said Lawrence. “I had a girlfriend for a while but we had to sneak to see each other. There was another black girl in the school who was more like a sister to me. She was captain of the cheerleaders. When prom time came we had to go together. She had no boyfriends either.”

Today, Carol and Chuck Lawrence feel it is their responsibility to protect their daughter from racism they believe still exists. Maia attends a racially mixed school, and the Lawrences say they will discourage her from attending one where she will be the only black or even one of just a few.

The Hasties also have similar plans outlined for their children, 10-month-old Carl and three-year-old Karen.

Cassandra Hastie was raised in St. Louis and did not attend an integrated school until high school. William, 39, is the son of William Hastie, Sr., the first black federal judge in the United States and a major strategizer of the Brown vs. Board of Education lawsuit that eventually brought about desegregation in the public schools. The Hastie family lived in an integrated neighborhood in Philadelphia but he said he felt the burden of racism.

Today, the couple hopes to provide “a rich cultural and historical base for our children,” said Cassandra. “If necessary, when it’s time for my daughter to go to school, we will drive her into San Francisco every day, if that’s what it takes to find a well integrated classroom.”

Sundays, the family attends church in a lower-income black community, a few miles from their luxurious neighborhood. “There’s a little girl there about the same age as my daughter and I hope they become friends,” added Cassandra.

Like the Hasties, all except two of the people interviewed said they socialize with whites. That is in keeping with the thesis of “Habits of the Hearts,” a highly celebrated book by University of California sociologist Robert Bellah, which explores characteristics of contemporary culture. Bellah believes that in addition to drawing attention to injustices, the Civil Rights Movement made many Americans, black and white, recognize that although they are different, they share many of the same concerns. This, he suggests, paved the way to the formation of lifestyle enclaves, a phrase he uses to characterize relationships based on shared societal conditions such as professional status, education and financial power. The theory asserts that today, many Americans base friendships on shared concerns, such as tax shelters or private schools for their kids, rather than common histories.

However, during a recent interview, Bellah said that despite their interaction within those enclaves, blacks, because of racism, are often “activist oriented,” generally working to assist poorer blacks.

Indeed, many of those interviewed said the racism they encounter sharpens their commitment to the black community. They reason that if they, as professionals, are not fully accepted, it is vital to help blacks who live in poverty, who are victimized by racism.

For those reasons, therapist Gene Mabrey, 40, volunteers much of his free time in clinics and attends special events in his old community. Mabrey was raised in San Francisco’s Hunter’s Point projects, fought in juvenile gangs, served time for petty crime, dabbled in drugs, and in general lived so hard that at 18 he wound up in the hospital with a perforated ulcer.

Today he has a Ph.D. and works for the county courts. He attributes his success to nurturing by blacks such as Congressman Ron Dellums, who in the ’60s, worked as a social worker in Mabrey’s old neighborhood.

Said Mabrey, “I’d never even seen a black professional before that. Their message that life could be better kept me going.”

Twenty years later, Sheila Stainback believes that as a role model for so many, she still needs an optimistic message to take back to her old community. But she worries that the racism she and other high echelon blacks feel will send a confused message to those who have been left behind, ultimately impacting all of society.

“Any degree of hope that we share should not continue to be dashed. Our message filters down. We pass on the word that there is a chance for other blacks, that they should press on and continue striving for success.”

©1986 Brenda Lane

Brenda Lane, a reporter on leave from the Oakland Tribune, is reporting on America’s new Black middle class.