On a typical weekday morning, black women are blazing new trails across America.

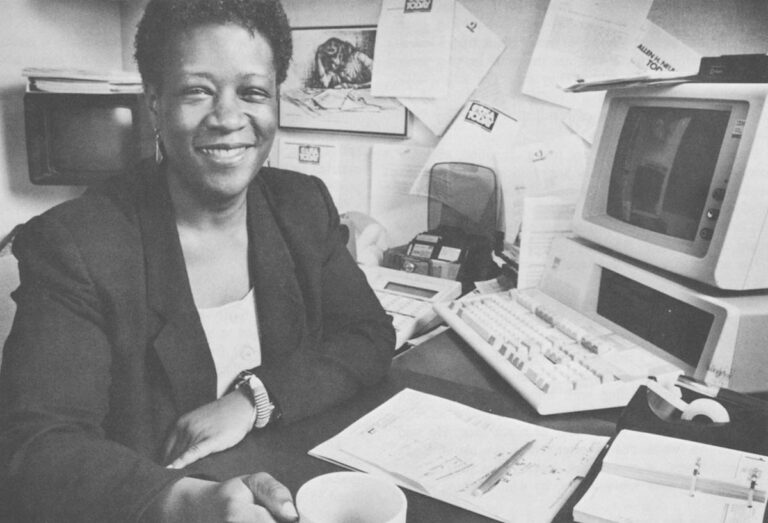

In the nation’s capital, Karen Howze, 35, a managing editor for USA Today – circulation 1.4 million – joined the paper’s other editors for a daily story conference.

At the U.S. Senate, Deputy Sergeant-At-Arms Trudi Morrison, 36, prepared for a working lunch with Senator Robert J. Dole. As second in command for administrative and protocol needs, she oversees 2,200 employees and a $ 100 million budget.

In New York, Mary Ann Spraggins, 38, vice president for Salomon Brothers, the big investment banking firm, received a call from the director of the state agency her company has been wooing. Spraggins’ bid for a $200million municipal bond deal has been approved.

In Lawrence, at the University of Kansas, vice-chancellor Marilyn Yarbrough, 40, turned to draw a chalk diagram during a law seminar outlining the details of a runoff primary.

Young, gifted and black, they seem to have it all. But except for Morrison, their personal lives mirror those of many other black professional women. Many have had to postpone or abandon plans for marriage and family. In their strivings to succeed they have separated themselves from the bulk of America’s black men.

Statistics explain part of the story. To begin with, there are 1.5 million more black women than men. According to a 1985 survey by the U.S. Department of Labor, only 47 percent of black professional women are married, compared to 62 percent of their white counterparts. The study also indicated that while there are 560,000 black women professionals, there are only 287,000 black men professionals–little more than half as many.

And the future is not promising. According to the 1980 U.S. Census, black males are not entering white collar fields as rapidly as black females. Of all blacks enrolled in colleges, 60 percent are women. Of those blacks who graduate, 70 to 80 percent are women.

Hidden beneath the numbers are the problems black men have faced in American society. “Their numbers have been decimated by homicide, suicide, casualties in Viet Nam and unemployment,” says Bebe Moore Campbell, an author who specializes in ethnic issues.

During a period of two months, I interviewed 19 black women whose names I chose from lists compiled by acquaintances from around the country. In their mid-thirties and early 40s, they represent the best in American education. They are graduates of universities such as Harvard, MIT, University of Pennsylvania, and Bryn Mawr. Seven completed law school and three medical school. Their average salary is $61,000. All but five came from a two-parent family. Seven are married, seven divorced. Of course, not everyone wanted to be married. But of the 10 who do want marriage, half said they have given up trying to find a mate.

In Lawrence, Kansas, professor Yarbrough, who is divorced, shares a roomy house built in the 1850s with her two teenage daughters. Downstairs, in the stone basement, there is a sealed-off passageway.

“It once led to a tunnel,” explained Yarbrough. “This house was a stop-off point for the underground railway.”

The irony is not lost on Yarbrough. She, and other blacks have worked hard and come far since the days when that tunnel meant the difference between freedom and a life of auctions and beatings for blacks. She has come so far, yet her strides have put her an arm’s length from a mate.

“The fact that I’m not dating anyone is not unusual,” said Yarbrough, whose earlier marriage to a black professional ended in divorce. “My friends in Tulsa and Charlottesville aren’t either.”

Their dilemmas are caused partly by disparities between the romantic visions of who they want, and the realities of who they are. Practical options for them would be working class black men or interracial marriages. But they generally find neither acceptable. Some of the women have dated blue collar men but none have married one. They want men who have similar backgrounds: college educated, high salaried, living in upper-scale neighborhoods where they are enjoying the good life. And overwhelmingly, the women I interviewed said they want those men to be black. In fact, many were willing to forsake their dreams of marriage and children if it meant not having black men for husbands.

As a result, the high demand for black professional men has become emotionally expensive to those not fortunate enough to meet the right mates.

In Washington, DC, USA editor Howze said competition for professional black males has hit an all time high.

“A lot of black women in this town will do anything to have a black man who is a professional,” she said. “They buy them cars, pay their rents.”

Last year, Howze adopted two children. These days, her early morning weekdays are spent performing the tasks she watched both her mother and father share when she was growing up in Detroit. First she readies two-year-old Karie and three-year-old Charlene for the day, drops them off at a nearby child care center, then rushes to the office. Howze said she can’t imagine herself married anytime soon. She is not willing to dive into the diminishing pool to struggle for a man.

In Los Angeles, Cassandra Durant, 34, a staff assistant to the owner of a textile company, feels the competition edged her out of her marriage to an up-and-coming politician.

“Women used to leave their telephone numbers on his car,” Durant said. “A flight attendant slipped him a note on the plane. When I went to City Hall, young black women were all over him.”

Some social critics believe that a profound distrust exists between many black men and women as a result of the violent and ugly slave history they share. This tension forestalls many lasting relationships, critics say, and the career imbalance only exacerbates the problem.

The theory became the subject of national discourse in 1979 when Michele Wallace wrote “Black Macho and the Myth of the Superwoman.” Wallace attempted to show how tension developed between black men during slavery, as black women were abused by their white masters. The men were virtually unable to protect their women and the women may have been somewhat resentful that they could not.

Recently talk of that kind of tension has resurfaced with the movie, “The Color Purple,” based upon a book by Alice Walker. Black intellectuals such as Wallace, have debated the script’s portrayal of black men. Some feel the movie was rife with symbols of emotional castration–a long-standing complaint about black women by some black men, who accuse them of being too bossy and too pushy in relationships.

Vice Chancellor Yarbrough said tension between black professional men and women has resurfaced. “I’ve gone to restaurants, parties where I’ve heard black men I know to be generally very rational get involved in very irrational arguments,” she said. “They say, ‘I’m angry with Alice Walker.’ But I think it’s really symptomatic of an underlying problem. A lot of black men are angry with black women for succeeding.”

One woman, who asked not to be identified, said her success is causing problems in her relationship. “My husband is loving and supportive. But I feel tension in the relationship each time I get a promotion,” she said. “I can understand it. He’s just as motivated as I am, even works longer hours. But he’s tall, dark and handsome. Those are qualities that may spell success for a white man but not for a black one.”

While racial prejudice creates a web of complexities in the workplace for blacks regardless of sex, one psychologist believes black men face special problems. Ron Brown, who owns a management consulting firm in San Francisco, where he works with Fortune 500 executives, focuses on issues dealing with minorities in the work place. Brown said a seldom discussed but major issue in corporate America is sexual fear of black men. He said many of his white clients often complain about black male employees or co-workers, fearing that they’re preferred sexually and romantically, by white women in the office.

“They ask me questions like ‘what do the women see in him? What’s so special about the way he looks?’ “

Brown said another factor that keeps black men from moving up the career ladder is that racial stereotypes cause white supervisors to misinterpret their body language.

“Even something as benign as pounding a fist on a table can generate anxiety among white males,” Brown said. “When these men raise their voices or ask difficult questions, they are perceived as threatening.”

But even before they make it to the lower rungs of the corporate ladder, Bebe Moore Campbell, the author, feels black men start out at a cultural and historical disadvantage.

“Except for the middle class, intellectual competitiveness is not one of the devices used by black males to tout masculinity,” said Campbell. “The typical working class male favors being athletic, fearless and sexual. And as a people we tend to listen more to music than read books. All that is fine, but it doesn’t help to pass college entrance exams.”

Campbell said historically, black women were given incentives to go to school, while black men were not. “After the slaves were freed the women were able to get jobs as maids and cooks. And at home, they were told by their parents that if they wanted to get up off their knees from scrubbing Mr. Charlie’s floors, they’d have to go to school, become teachers. The men went in the direction of the fields, not toward schools. Even today black males have the highest high school drop-out rate.”

In the black community, the shortage of men is nothing new. What’s changing is the insistence by many black women on having a mate of equal or higher professional status. And it reflects a fundamental shift in the way potential partners are viewed.

As a child growing up in New York during the 1950s and 1960s, I knew black professional women who were married to blue collar men. Back then, however, the word professional had a narrower meaning for blacks. They were registered nurses, teachers, and social workers working in jobs that seldom paid enough to support a family. Most of the married men were the major breadwinners.

In my own family, an aunt who was a nurse was married to a carpenter. My best friend’s mother, a social worker, was married to a musician. And my mother, a divorcee, was a legal secretary and self-styled entrepreneur. She managed to buy our 13-room house in Flatbush with money earned from her book of children’s poetry, and sent us to college with profits from one of the first jazz and exercise records that she composed and produced. During these ambitious projects she dated a janitor, then a subway conductor.

The expression that we were “all in the same boat” was almost literal. Except for the few of us who lived in integrated areas, most of the middle class black population lived in black ghettos. Even if one didn’t live there, the rest of the family did. Although it was not talked about, there was the understanding that because of racism, black people, no matter how hard they worked, would not be able to rise in large numbers through the professional world.

Those women not “lucky’ enough to be married to one of the lawyers or doctors but who still wanted to fulfill their middle class yearnings dressed up, and on Saturday nights they went to a fancy but usually segregated club. Sunday mornings they attended churches with other people of their ilk. The support they felt from the black community helped to affirm their marriages, no matter how professionally unbalanced they might be.

Many of the changes accomplished by the Civil Rights Movement were ushered in by the emerging black professional class. For the first time it was no longer acceptable for Audrey, the executive, to marry Sam, the truck driver. Audrey and her friends were learning a new language, that of corporate culture, one that dictated that if Audrey was invited to a company outing, she would be expected to arrive on the arm of a man who could converse intelligently with the other guests, whomever they might be.

Although they are seldom discussed, there are victims of this change. When Bebe Moore Campbell wrote a story on what she called “cross class dating” for “Essence” magazine recently, she said she received several letters from black men “who are very hurt.” They feel looked down on. A few men told me that when they meet a woman, the first thing she wants to know is where they work and what they do.”

Although most of the 19 black women interviewed said they would be willing to marry across class lines, none had. Those who were married had found equally successful and ambitious men.

Trudi Morrison of the Senate, for example, was trained as a lawyer and as a classical violinist. At one point she dated a janitor. The relationship eventually faltered, but not because of the kind of work he did, explained Morrison. Today, she is married to an attorney.

Vassar educated Jo Ann Gray-Murray, 36, who is a director of admissions at Williams College in Massachusetts, said she also tried dating blue collar workers.

“I felt I had to suppress certain ideas or put on a mask,” said Gray-Murray. “When I dated one man I pretended I wasn’t very smart. Then the next day I’d go back to work and be myself again. Soon I started feeling schizophrenic.”

In Roritan, NJ, Nancy Lane, 40, a vice president for Ortho Diagnostic Systems, will not consider a blue collar man.

“I’m only interested in men who are high achievers,” said Lane. “I’ve worked hard to achieve a certain lifestyle and I want whomever I’m with to feel comfortable in that setting.”

In Los Angeles, Cassandra Durant is no longer looking for a mate. She recently became engaged to a bus driver. The two are learning from one another, Durant explained. She is teaching him the fluent French she speaks, and introducing him to the joys of vegetarian cooking and ballet. He, in turn, is teaching her about southern-style food, football and western movies.

Durant believes a lot of black professional women are missing out on meaningful relationships by eliminating working class black men. She feels that lack of education and job status does not have to mean lack of intelligence and sophistication.

“I feel as if I’ve stumbled across a new flavor of ice cream,” said Durant. “My friends are looking at it warily. They don’t want to taste it, but I feel like smashing it down their throats to just make them give it a try. I tell them there are black bachelors all around us. They’re in elevators, grocery stores, libraries, parking lots and gas stations. It’s as if these women are wearing glasses that filter out everybody except the men in three-piece suits.”

Durant believes that many black women suffer from low self-esteem, and that affects their choices in mates.

“Black women have not awakened to the reality that a man is not going to elevate us in society,” said Durant. “But we keep trying. We have big gaping holes inside us. We live in a society where we’ve been told that our breasts are too small, our buttocks too big, our noses too wide. We are looking for men to make up for our deficiencies.”

Interracial dating patterns are showing no signs of change. For years however, some social observers predicted that as black women continued to move up, they would become part of the “Lena Horne syndrome.” The term sprang from an Ebony magazine interview with the star. Horne explained that she had married a white man because as she moved up the ladder of success there were fewer black men to choose from. Thus, the theory went, with continued ascents, black women would begin to marry more white men.

But that did not happen. According to the 1980 Census, the percentage of interracial marriages has remained steady in the last decade. With 175,000 black-white marriages in the United States, only 64,000 are black women married to white men. Also, 17 of the 19 women I interviewed said they would not consider marrying out of their race.

“Absolutely not!” said investment banker Spraggins, when questioned about interracial marriage.

“I may be a vice president of one of the most powerful and prestigious firms in the world, but when I walk out of here and try to get a cab the drivers don’t stop because they assume I’m going to Harlem,” she said.

“As long as my fate depends on how fast I can whip out my Salomon Brother’s card, I know it’s an arbitrary fate. But it’s a reminder that my future is tied in with other black people.”

Some black women believe there is a special communication between black couples that is lost in interracial marriages.

Mindy Fullilove, 35, a psychiatrist practicing in Oakland California, is mulatto. Her mother is white, her father black. Her former husband, to whom she was married for 10 years, was white. Fullilove is now married to a statistician who is black.

“There is a covert language that exists between blacks,” said Fullilove. “When you’re married to someone white you have no one to share the dialogue with. That makes it harder to cope.”

Seated in her office, Fullilove was wearing her long, light hair pulled back into a bun. “The other day, after I’d seen several clients, I got a flat tire on the way home. I came home exhausted. But I told my husband that at least I’d been lucky in one way. A man had pulled over and changed a tire for me. And Robert said, “Honey, luck doesn’t have a thing to do with it. That man pulled over because you’re fine. You’ve just got to accept the facts.’ “

“That was all he said,” continued Fullilove. “It was not what he said as much as how he put the words together. He was rapping. And it made me feel good. Rapping is not something that’s limited to teenagers hanging out on corners. It’s part of our way of communicating. A word like (fine) can have many different meanings. And that day they all made me feel comfortable.”

Fullilove continued, “A black man who is accomplished and sure of himself, who can articulate his feelings and ideas, is inimitable. He’s a winner, and he’s someone everybody wants.”

But Barbara Nappi, 32, an investment counselor for Shearson Lehman investment bankers in San Francisco, is married to a white man with whom she says she has no problems communicating.

“It’s unfortunate that people attribute that kind of communication to race,” said Nappi. “My husband comes from an Italian background. His grandmother only speaks Italian and it is spoken regularly in his parent’s household. But he and I communicate just fine.”

Nappi had always said she would never marry or date anyone white. In fact, she said marriage was the last thing on her mind when she met her future husband. They both worked in the same office, where he was communications director. Thinking his manner too abrupt with her and other co-workers, Nappi tried consistently to have him fired. Eventually, mutual friends got them together.

The issue however goes beyond black or white, working class or professional. The question may be whether or not women are too complex to sustain a relationship. Therapist Brown said because of the double whammy facing black women–of racism and sexism–they require almost a single mindedness to move up.

The 19 women I interviewed are driven. Some feel they have to be three times as good as whites to succeed. Commissioner Sandra Brown Armstrong, 39, of the Consumer Product Safety Commission, was working full time as a policewoman in Oakland, when she entered law school. By working all day, attending classes at night and studying until the wee hours, she graduated seventh in her class.

Investment banker Spraggins was not merely content with one law degree from New York University; she went to Harvard for another.

Newspaper editor Howze, who spent seven years in a convent preparing to be a nun, eventually joined the staff of the San Francisco Chronicle, covered the criminal courts, and also earned a law degree.

The lives and psyches of black women like these were explored in 1981 by clinical psychologist Diane Adams of San Francisco for the University of California. Adams found them to be unrelenting competitors who had been encouraged by their parents to achieve, and who saw hard work as a way of earning affection.

“They were depressed when not able to achieve,” said Adams. “They drove themselves. Many worked 14-hour days.”

That kind of ambition would appear to be at odds with the traditional role of a wife, but said that was not the case with the women she studied.

“In fact,” said Adams, “they worked overtime to be the most attentive parents, the most loving wives, the greatest community activists. They feel a need to always be the best at whatever they do.”

Adam’s report is limited to the psyches of these women. Not enough time has passed for an intelligent observation of how this group will evolve, or how American life will continue to be impacted by their developing numbers.

By casual observation, most of the women I interviewed seem almost Victorian in their insistence on marrying men of the same class. But closer scrutiny did not point to elitism. As high powered executives, many felt it almost impractical to marry men who couldn’t comfortably fit into their lifestyles. They wanted men with whom they could discuss business strategies, men with their own corporate savvy and know-how. And many felt their career accomplishments could easily overwhelm blue collar men.

Like many successful women, most had enjoyed nurturing relationships with their fathers. It is probably not surprising then that psychologists and the women themselves say they are looking for updated versions of their fathers. That was one of the explanations given for their feelings about interracial marriages.

But there is also bitterness about whites. Theirs is the last generation to have first-hand knowledge of segregation. They have not forgotten. And they are sensitive to racism that still affects them, and other blacks, in their neighborhoods and on jobs. In short, their experiences have made them racists.

According to Diane Dean, 36, a program director for an engineering council for minorities in New Jersey: “I have been asked out by white men on several occasions but I always feel suspicious of their motives. I’m not against interracial dating for other people, but I simply haven’t been able to come to grips with it. In the back of my mind, when I think of black women with white men, I’m reminded of times I’ve read about during slavery when the masters used us to instruct their sons–for the purpose of teaching their offspring about sex.”

Their rigidity on these issues may well give way in coming generations. Or perhaps, now that the problem is being discussed, new options may become available.

©1986 Brenda Lane

Brenda Lane, a reporter on leave from the Oakland Tribune, is reporting on America’s new Black middle class.