I don’t trust any generalizations about organized crime, not even my own. It’s a subject that inspires extravagant overstatement. People discussing the mob become like blind men describing an elephant, giving the big picture when they’ve only felt part of the beast. Some examples:

I have a friend who spent a chunk of his life investigating organized crime for a federal force that never officially existed. He’s convinced that the new boss of bosses is a low-profile hood in Brooklyn who was given the title by a ruling council in Sicily.

I know a retired Scotland Yard detective who has become an expert on American mobsters. He says that anyone can see that Jews are the real bosses, and he names five men who run everything. But financial power seems to be the sole credential needed to make his list.

Then there’s a scholar whose writings on organized crime seem to be gaining in influence. He says the Mafia is a myth and mobsters are simply entrepreneurs who deal in the illicit. I had lunch with this man a few years ago and was surprised to find that he had never met a real, live hoodlum.

Maybe all three have a piece of the truth–I don’t know. I’m going to try to avoid error by sticking close to specific detail.

My purpose is not to glamorize nor to crusade, but rather to try to understand. I’ll be writing about people who became involved with the mob, hoods and their associates. All of these people examined the landscape, both external and internal, and made decisions that some might condemn. I can’t quite do that. Maybe it’s a legacy from a decade of investigative reporting. During the course of an investigative project, I used to use outrage as a tool to help me keep working, saying to myself: “This guy’s a real son of a bitch.” But toward the end of a project, before confrontation interviews, I’d turn the thing around and ask myself: “If I had lived this man’s life, and went through all that he’s gone through, would I have done anything any different?” I could never answer the question.

The first segment deals with motivation–why someone gets involved with the mob. The principal figure is a mob informer named Herb Gross, a man I’ve been talking with for seven years.

His recollections are supported by extensive court testimony and by other interviews I’ve had with persons who know him well: relatives, police, prosecutors, and crooks. Something about Gross seems to bring out the Biblical. Ocean County’s chief of detectives, Capt. William Gallant, says that Gross has the best recall he ever encountered, adding: “I can’t imagine that Herbie would ever bear false witness.”

Look what has become of God’s favored one, little Herbie Gross. He’s stranded among strangers in Middle America, trapped in a failing, flabby, 65-year-old body; trapped in a tiny, two-room apartment in a public-housing project; trapped near the end of a life that was supposed to turn out swell, but didn’t.

It’s an old story, maybe the oldest, about how pride can do you in. Let’s have an Old Testament version for Herbie–Ecclesiastes 1:1, modified:

Vanity of vanities, sayeth some ancient Jew, all is vanity.

And maybe so. Maybe vanity is a prime motive for us all, lurking there behind altruism, behind duty. We do what we do because we think it’ll make us look good. The millionaire drives himself not for the riches, but for the admiration riches bring. The lonely artist struggles for years, not for art’s sake but for anticipated glory. And Herbie joined the mob to be significant at last.

“You want to make some kind of impact in the world,” Herbie says now. “You don’t want to end up just dust-to-dust. That is something that has motivated me from let’s say my middle teens on. And I was conditioned by the constant praise that was heaped upon me ever since I was a little boy.”

Growing up on New York City’s lower east side, Herbie Gross came to understand that much of what his parents did, they did for him, so he could have better. His father and mother were both immigrants, Hungarian Jews. They met in New York and soon after their marriage, they opened a small tea room on East Sixth Street.

As a boy, Herbie used to enjoy watching card players who lingered at their tables in his parents’ place. He liked the gypsy violin music, too, and delighted his mother by scratching out a tune the first time he tried to play. His parents felt they should encourage a natural talent and money was found for violin lessons.

Soon Herbie was winning amateur-night contests in local theaters. At age 11, he appeared on a children’s radio show in New York and played so well that the station gave him a show of his own, “Herbie Gross and His Violin.” The program drew no sponsors and lasted only two months. Herbie continued his violin studies for years, attending the Juilliard School, aiming for a career in music. In his early 20s, he assessed his abilities and concluded he would never be a great violinist. He decided to put music behind him: if he couldn’t be outstanding, he would have to find something else.

He went to St. John’s Law School for two years. Then his enthusiasm faded and he dropped out, disappointing his parents, particularly his father. The treasured son tried to explain why he had given up, finding factors outside himself. He said that he had become cynical about lawyers, judges, and the law. He saw deep significance in the indictment of a respected New York Judge on bribery charges.

There was a less idealistic explanation circulating among Herbie’s relatives. The willful young man quit law school because he was distracted. He was running around with a married woman.

Perhaps his parents had been too lenient and had given him too much. His sister Janet, two years older, always got less attention. She worked her way through college and law school, resenting the prodigy. She became a lawyer, married a lawyer, and her daughter is a lawyer.

The little tea room was just a beginning for Herbie’s parents. With family help, the Grosses were able to buy a 70-room hotel in the Catskills. That meant busy summers and unproductive winters. Herbie’s father, Martin Gross, began searching for a winter business to balance their lives. In 1941 he bought a 17-room hotel in Lakewood, New Jersey.

Martin Gross came to Lakewood near the end of the area’s boom as a resort. His son Herbie wasn’t much help with the new hotel. Herbie was an unhappy and aimless 24-year-old. He took off for Miami with Regina, the married woman he found so attractive. Regina was pretty, but four years older than Herbie. She was Jewish and her family came from Hungary, but Herbie’s relatives looked down on Regina’s folks as common people. Herbie became a cab driver to earn enough money to stay in Florida. Regina got a divorce and then she and Herbie were married, shocking his family.

Herbie Goes to War

World events were changing lives, altering plans. Hitler was advancing across Europe, Herbie, classified 4-F, thought he wouldn’t be drafted. But in July, 1942, the Army decided Herbie was healthy enough to fight. He served 28 months overseas, mostly in China and India.

It was a long war for Herbie. A severe case of dysentery left him too weak for the Army to discharge him until early in 1946.

“I went to Lakewood after I was discharged from Fort Dix,” Herbie recalls. “I spent the day there and then went into New York to meet my wife and also to buy civilian clothes and to get ready for civilian life. Eight days later, on the 19th of January, I got a call in New York that my father had been killed in an accident in Lakewood. I got the call at about 10:30 at night.

“Anyhow, I got out to Lakewood and discovered that he had been run down by a drunken driver as he was getting out of his car. My mother was describing the scene, and this affected me terribly. She mentioned that he was saying, right up until he drew his last breath: “Murderers! Murderers! They killed me!…”

“I went to the hearing in municipal court. The following day, it was a Sunday, they held a hearing, a special hearing. And his license was revoked for drunken driving and he was held for action by the grand jury on a charge of causing a death by auto. On Monday, my father was to be buried in New York, and so my mother, my sister, and myself had to leave. So I called the prosecutor in Ocean County…I gave him an address where we would be in formal mourning.

“Now, I tell you this story in detail because, actually, this was the start. This incident started everything going in my life that eventually led to joining with the mob.

“I told the prosecutor where we would be in case this guy took an appeal. And we would be there for several months, because we would have to straighten out my father’s estate in New York. In April, we hadn’t heard anything and we returned to Lakewood. I called the prosecutor’s office to inquire as to the status of this case against this 21-year-old kid. I’m told that he had what was called a triad de novo (new trial) and he was found not guilty.

“I said, ‘I want a copy of the transcript. I’ll pay for it.’

“They said, ‘You can’t have it. You’re not a party to the thing.’

“So I went to the local newspaper office was thrown out by the publisher himself, who turns out to be a County Court judge, the guy who sat on the trial dc novo. So, directly across the street was a weekly, the Citizen, and it was published by a man named Johnson. I went in there and told him the story. I said that it’s obvious that there was some kind of fix here….I told him that the prosecutor wouldn’t give me the transcript…He says, ‘Well, try to get the transcript and then come back to me.’”

“I went down to the County Court and I started to raise hell there. I had cash. I said, ‘Here’s my money. I want to know who the court reporter is. You don’t control him. It’s a public document. I want a copy of it.’”

“So, I got to the guy and I paid for it…I read it. They had all changed their testimony.”

“I went to Johnson at the Citizen. He said, ‘I’ll tell you what I’ll do for you. You write a letter to the editor and I’ll print it on the front page,’ which is very unusual. He put it in a black-bordered box, right in the dead-center of the front page. In it, I wrote this letter. I accused the County Court…the prosecutor, the police officers, and the police doctor.

“Now, I expected to be pinched for criminal libel…Not a word. Not one kickback from the public showing indignation and curiosity…Well, the upshot of it is that the boy’s father did call and he came over…‘Here’s my bankbook. I’ll sign over everything. I feel terrible.’

“I told him to jam it up his ass: ‘We’re not even going to sue. We don’t measure my father’s blood in dollars…'”

“I was going to take a job, which I eventually did, as a meat salesman in New York City, with a large company. And I told my mother…‘One day I’m coming out to Lakewood. I’m going to follow every individual and every politician in this county to their grave. I’ll have enough money. You’re going to help me. I will not work. That will be my life. Digging up records.’ “

Is it possible for any individual to know with certainty the motive behind a personal decision? We’re all experts at self delusion and rationalization. There’s a smorgasbord of reasons for every action. We pick the ones that are most palatable.

Eventually, Herbie did move to Lakewood, but not until 12 years after his father’s death. Vengeance may have been a factor, a simmering need. The way that Herbie reconstructs it now, he couldn’t move until he had put some money away.

Herbie looks back with pride on his early years in Lakewood, seeing himself as the community’s first citizen. He kept his vow and became a regular speaker at public meetings. Reporters covering Lakewood then found him to be a bore, but always logical and sometimes effective.

After a while, even his successes seemed empty to him. Herbie grew weary of the critic’s role. He wanted to be a star, run for office, make the decisions. But party leaders couldn’t see this loudmouth as a candidate. A rebuffed Herbie found another way. He became a bagman–the fixer who delivers governmental actions for cash.

He loved it. Herbie Gross, he was entitled, and he was finally pulling the strings. He already was a crook when the local mob boss reached out for him with an invitation to join forces.

Ecclesiastes 5:8–”If thou seest the oppression of the poor and violent perverting of judgment and justice in a province, marvel not at the matter; for he that is higher than the highest regardeth, and there be higher than they.”

Ecclesiastes 7:15–”All things I have seen in the days of my vanity: there is a just man that perisheth in his righteousness, and there is a wicked man that prolongeth his life in his wickedness. Be not righteous over much; neither make thyself over wise: why shouldest thou destroy thyself?”

It’s a gloomy book, Ecclesiastes, almost agnostic in tone. Herbie keeps driving me there, looking for understanding. He talks a lot about his Jewishness, about his pride in being born a Kohen, the priest and law-giver caste in Jewish tradition. But Herbie picks and chooses. Martin Luther said every man could be his own priest. Herbie goes further. He creates his own religion out of bits and pieces of Orthodox Judaism.

“My Uncle Was Moses”

“I’m a high priest,” he says in a confidential tone. “In the Orthodox community, especially when you go to synagogue on the high holy days, they get to know what crowd you are. And the high priest is the highest, not a rabbi. The rabbi is never the highest. The rabbi can not bless another Jew. Only I can bless another Jew.

“It’s handed down from father to son. I’m a direct descendant of Moses and Aaron. When Moses came down from the mountain with the tablets, and he told about the conversation with God, as he was being given the commandments, that his brother Aaron and his descendants shall be the high priests, the so-called circuit judges today, deciding disputes between Jews…

“And so whenever I would hear somebody say that their ancestors came over on the Mayflower, I would say, ‘My uncle was Moses.’ And it’s true. I mean, I can joke about it and laugh about it, but it’s true.”

How could a high priest become a bagman? How could a Kohen become the Jewish brains for some New Jersey mobsters, for that’s what Herbie became. I once asked him if God was looking over his shoulder while he was going through it all.

“I always felt that way,” Herbie replied. “I always felt when I reflected on it, even during these things, that eventually I’m going to have to answer for all these things. And I better have some good arguments for my God. I used to put it almost jocularly. When I appear before Him at the final judgment, we’re really going to have a wrestling match, because I’m going to justify these things, maybe not rightfully so, but I’m going to justify these things.

“I’m not going to stand before Him and say, ‘Well, I’m a crook. I’m a thief,’ I’m going to give Him the reasons why I embarked upon these ventures and changed my life…I always felt I was cut out for leadership. I always felt that I deserved recognition because of my mental agility, ability, and my own inner feelings that I am a cut above the average person. And I depended upon the average person to recognize these things and give me this eminence that I was entitled to. And I was not getting it. So fuck ’em all. I’ll get it this way.

“Now, I don’t say that I am right in the final analysis. I’m probably, almost definitely, wrong. But this is one of the major reasons that I say to myself that pushed me into that way. Recognition.

“I feel that God, one part of Him is a rational person who will tolerate discussion. He’ll hear you out…If anybody understands His own people, all His creatures, it’s God. If He doesn’t understand them, if He doesn’t make allowances for their shortcomings, He should have destroyed the people in this world a long time ago.”

He’s beautiful, my friend Herbie. He used to be a source of mine, but now he’s a friend.

I’ve known him for seven years. We were brought together by a man we both respected, Joe Cranwell, then head of the federal Organized Crime Strike Force in Newark.

Joe liked the idea of investigative reporting and he gave me a little help when he could. He arranged for Herbie to call me at work after I explained a problem I was having. I needed to “mob up” a minor figure in an investigative project. I knew that the guy was connected, but it’s difficult to identify someone in print as a racketeer or mob unless you have some hard evidence, such as court testimony or government reports.

Herbie already had turned informer and was part of a new and evolving federal program designed to convict mobsters, the Witness Relocation Program. The minor figure in my story was based in Lakewood and, from Herbie’s past testimony, I figured that he must know the guy. He did and his recollections helped solve my problem. In the years since then, Herbie has bounced around a bit, but he always stays in touch. Often my office phone would ring and the operator would say, “Will you accept a collect call from Herbie?”

I would smile and say, “Sure will.” He has always been Herbie, not Herbert or Herb. Even now, when he’s in his 60s, when he’s introduced to someone, he says, “Call me Herbie.” I think it’s a way of signaling openness.

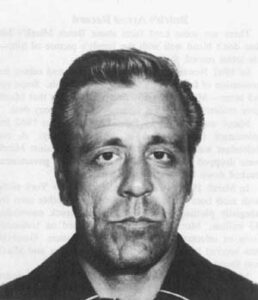

The name doesn’t really fit. He’s not diminutive. Herbie’s 6-foot-1, usually overweight, anywhere from 210 to 240 pounds. His face is pockmarked and he looks at the world with wet, self-pitying eyes. If it weren’t for those eyes, he could pass for what he might have become, a retired Jewish businessman. If not for the eyes, he would blend in well in Miami Beach, taking the sun, playing a lot of cards, occasionally getting to the track.

Instead, he sits in the north, in his public-housing project, near a hospital where he’s an out-patient. His health is poor. Surgery seems to have controlled cancer of the bladder, but the doctors can’t solve a spinal problem and his left leg is numb.

He’s just waiting for the end now, a lonely man, finishing his life among strangers, living under a stranger’s name. But he has planned a final satisfaction. He will be buried as Herbert Gross.

Herbie joined the mob almost the same way he left his wife, slowly, inch by inch. Both processes were taking place at about the same time, in those middle years as he was sliding toward his 50th birthday. Sometime along in there, married sex ceased to be a joy.

Herbie and his wife, Regina, thought they were destined to be childless. After all, they had been trying for 10 years, and, before that, Regina had tried for 12 years with her first husband. Then came the “little miracles,” first a daughter, and a few years later, a son.

Is it surprising that Regina became caught up in motherhood, a role she had yearned for? It seemed to Herbie that little else mattered to her. She certainly didn’t seem as eager for sex. But then, his invitations weren’t inspired:

“Come on, it’s time.”

And she would say, “I’ll be in soon.”

And Herbie would fall asleep and awake the next morning feeling that he had been gypped somehow. This was in the early 1960s, before supermarket magazines told husbands and wives to discuss their sexual needs. Herbie didn’t spell it out. He just moved some of his clothes from home to the hotel, so he could sleep over when things needed his attention. He began sleeping at the hotel more and more often, coming home for supper, playing the father, but not sticking around to be rejected as lover.

Herbie Meets Jimmy Sinatra

During this period, Herbie met the man who later became his boss, Vincent “Jimmy Sinatra” Craporatta.

(There’s no significance to Craporatta’s nickname. He’s not related to Frank Sinatra and he certainly doesn’t look like the singer. His nickname’s just a handle. Mob nicknames are functional, They’re devices that enable hoods to talk about each other with a blend of respect and intimacy. When underlings are discussing a boss, they can’t call him Mr. Craporatta, that would be too obsequious. But the last name alone would be disrespectful. “Jimmy Sinatra” solves the problem.)

Herbie’s first encounter with Craporatta came in a roundabout way. One day when Herbie was working at his hotel, a friend, Phil Katz, came to him with a business proposition of sorts.

Katz was excited. He saw a chance for big money, tax-free money: an opportunity to buy a numbers bank. Katz explained that the offer came from Ed Houston, a comparative newcomer to Lakewood. Houston, a huge black man with a menacing reputation, was an ex-convict who had served time for manslaughter.

Herbie and Katz decided they needed some expert advice. Herbie tried a local bookmaker. The bookie said he didn’t know anything about Houston, but offered to arrange a meeting with someone who should know, the bookie’s boss.

Herbie wasn’t thinking about organized crime as he drove out to meet Craporatta at a local dinner on a Saturday morning. He was just hoping for some straight talk.

Craporatta impressed him from the first. He was about 40, neatly dressed in working man’s clothes, a lumber jacket and boots. He wasn’t big, about 5-foot-10–a soft-spoken man with thick, horn-rimmed glasses. Over coffee, Herbie outlined Houston’s offer. Craporatta smiled a bit and gently advised Herbie to forget about it. “It’s probably all bullshit,” Craporatta said. He predicted that if Herbie went ahead with the deal, Houston would be back to him in a week with news that another unlucky hit had wiped out the operation.

Craporatta seemed to know what he was talking about. More than that, there was a warmth about the man and a candor that Herbie liked. When Craporatta smiled, Herbie found himself smiling, too.

Herbie took the advice of his new friend, Jimmy, and passed up the numbers racket. Events moved slowly for a couple of years. Occasionally, Herbie would see Jimmy in town and they would have coffee together. The conversation was casual, with Jimmy often kidding Herbie about his “conscience of Lakewood” role.

Regular attendance at municipal meetings had made Herbie an expert in how local government operates, all the trivial ins-and-outs of filing forms, who you see for what. Then, when he filed a rezoning application himself, he discovered the real secret of Lakewood government: you get what you pay for.

Herbie thought he saw an opportunity to make some money. An old, run-down hotel was for sale on a busy corner. The spot looked ideal for a gas station. The zoning wasn’t right, but Herbie figured he could get a variance because there were some other gas stations on the same road. He surveyed the neighbors and found no objections. But the Zoning Board rejected his plans in a 3-2 vote. Herbie hired a lawyer and appealed to Superior Court. Because the Zoning Board had made no transcript, the judge ordered the board to reconsider the case so he would have a record to review. Just before the new hearing, Herbie’s friend Phil Katz came to him, saying: “Do you want to win this thing, Herbie?”

And Herbie replied that he thought he would win-in court. Katz told him that he could win at the new hearing.

“How the hell are they going to vote against what they already decided?” Herbie asked. Katz gave a wink and suggested that Herbie talk with a former mayor. Herbie met with the man and was told that for $2,000, the vote could be adjusted from 3-2 against Herbie to 4-1 in his favor.

“Well, I only really need one vote,” Herbie said. “How about $1,000 and we make it 3-2 in my favor?”

No discounts, he was told.

Herbie paid the money and got his rezoning. He suspected that the men who changed their votes didn’t get the money. They were both well off, not the kind to scrounge for petty cash. But they were small-town, part-time politicians who had learned to follow orders.

This first venture in municipal corruption didn’t turn out well for Herbie. Just before construction was to begin, some residents filed suit challenging the rezoning. Herbie was surprised. One of the opponents was a local dentist whose office adjoined the gas-station site and who had supported Herbie’s application.

Herbie didn’t know another objector, Ed Freit, a real estate broker, but he called him anyway. Herbie asked Freit if he lived in Lakewood. Freit said that he did and added that he was active in the community as a member of the school board and a regional planning board.

“Great–you’re really civic minded and I respect you for it,” Herbie said. “But let me warn you about something. I think you got a few skeletons in your closet. Because you never appeared at that meeting and it was published in the paper that there was going to be a hearing on this thing…So, I’m going to watch you like a hawk, Mr. Freit, to see if you keep your nose clean.”

Herbie Loses His Rezoning

In Superior Court, Herbie lost his rezoning. Perhaps the board’s flip-flop made the judge suspicious. Herbie’s lawyer thought they could win on appeal, but Herbie told him to forget it. He was tired of spending money without a guaranteed return. Instead, he concentrated on vengeance.

Subsequently, he read in the paper that Ocean County was seeking federal funds to take over Lakewood’s privately owned airport. On a hunch, Herbie went to the courthouse and checked deed filings. He discovered that a few months earlier, the 240-acre site had been sold to a real estate investment group for $72,000. Only one investor was named on the papers–broker Ed Freit. Herbie checked further and found that the county had appraised the property at $358,000. That meant that Freit and his friends would make a $286,000 profit.

Herbie began blowing the whistle, softly at first. He stood up at the next Township Committee meeting and urged the town to investigate the deal. A little later, Herbie learned that two of Freit’s silent partners were county officials who had pushed the airport acquisition. At the next Township Committee meeting, he renewed his protests, now zeroing in on Freit’s potential profit. In the middle of all this, Jimmy Sinatra came to see him.

“Herbie, I want to ask you something as a personal favor,” Jimmy said. “I’d like you to back off on this airport thing. Some friends of mine are involved and I don’t want them to get hurt.”

The request came too late. Herbie explained to Jimmy that if the deal went through, everything would come out. He had made photostats of the key documents and had given them to the editor of a local newspaper.

Jimmy understood. His friends apparently got the message, too, and the county gave up on the Lakewood site. That meant disaster for real estate man Ed Freit. Within a short time, it was reported that he had pleaded guilty to a federal charge of income tax evasion. Later Herbie was told that the windfall profit could have meant a negotiated settlement for Freit, but without the money, there was no deal.

Herbie didn’t take much pleasure from his retribution over Freit.

“Personally, when I met his wife, who worked as a clerk in the high school there, and I though about his kids, I felt bad. Just like I feel for my family–what I did to them. I was a son of a bitch. He was a son of a bitch. Whatever we get and whatever he got, he deserved and I deserved.”

The rezoning fiasco had taught Herbie how to buy government. Soon, he began using that knowledge, playing middleman for politicians. It was a natural evolution. For years, little people had come to him for guidance through the maze of municipal government. But now Herbie could offer more than advice. He began dealing in results.

He had a partner in crime–Jimmy Sinatra. The alliance was born while Herbie was whistling down the airport deal. Jimmy had accepted Herbie’s explanation, but he invited Herbie to stop playing games and throw in with him.

“Look, you want to make money, don’t you? Don’t keep knocking yourself out for nothing,” Jimmy said.

For half the profits, Jimmy provided insurance. “In case of a renege or welshing, I’ll supply the people who’ll make the collection for you–for us–that’s what it amounts to–we’re partners.”

In Herbie’s memory, his decision to team up with Sinatra was influenced by the public’s reaction to his airport disclosures. He was disappointed when he didn’t hear cheering in the streets.

“I could see the public doesn’t give a shit. I got no reaction either way…At the Democratic Club meeting, no one paid any attention to me.”

And so at age 50, Herbie Gross became a mob associate. His justifications are every man’s alibi for adjusting the perception of right and wrong. He observed his world of Lakewood, NJ, and said two things to himself: 1) So that’s how it’s done, and 2) What a sucker I’ve been.

Later, his criminal activities widened. He became a financial counselor for hoodlums, and he engineered other crimes, including New Jersey’s biggest cash robbery–the 1968 holdup of Lakewood’s Fairmont Hotel. Thieves guided by Herbie escaped with $59,000 worth of jewels and $415,000 in cash. Herbie was a crook for five years. Toward the end, the mobsters didn’t bother hiding their connection with Herbie and he found himself in prison. He turned against the hoods. For 10 years he has been testifying against his former associates.

Herbie believes that his crimes seriously damaged his son, Marty, who was in high school when Herbie became notorious. At times, there’s a huge gap between father and son: they’re separated by almost 40 years and by widely different world views. Marty had to get tough quickly. His father’s activities made him a target for bullies. Marty turned to physical conditioning and martial arts.

Herbie talks with Marty in long-distance phone calls. Often, the conversation turns to religion.

“I tell him that he has a heritage that I hope will become a factor in his life sooner rather than later. ‘If you ever get to the point where you’re about to rip off someone or hurt someone for money, that’s the time I want you to sit down and say–Hey, God Himself made me something. What more can I want?”

Perhaps Herbie’s mood was somber because he had just returned from visiting his mother’s grave. She died a year earlier, but Herbie’s sister shielded him from the news. The Witness Relocation Program paid for Herbie’s flights to and from the cemetery after he threatened to quit the program. He was told that the program’s “resident Jew” had authorized the expenditure on humanitarian grounds. The cemetery was snow-covered when Herbie got there.

“I actually begged God in English for forgiveness for standing on contaminated ground, because one of the edicts is that I’m not to be standing where dirt is, dirt of a human being. If there was concrete there, I would be permitted to stand on it. It’s an awful responsibility, to be told that you may not be in the presence of a dead mother or dead father, because that’s mere dirt–the soul is God’s, that’s the person. And you, as a priest of all people, must keep yourself clean and pure. Because in the olden days, we were the judges. I think that is why I find it so easy, and it seems to come naturally, that I can judge people, because of heritage.”

He added, “I’ve told you many times that the thing probably of which I’m most proud is that I was born not just a Jew, but a high priest. While there were times when I lost sight of it, that’s when I was sucked in, eventually I saw there was no greater thing that I could claim for myself, than the fact that I was a high priest.”

The pride of being special–it’s a comforting element in many religions. But we’re all special and we celebrate the groups in which we can claim membership, the groups that help make us special, ethnic, national, regional, social–whatever we can use to distinguish ourselves.

Does Herbie push pride too far? Maybe so. He seems to be a man of his self-interested times. There’s a psychological phenomenon that may apply. In recent years American psychoanalysts increasingly have been using a new diagnosis to treat patients who search in vain for admiration. Such people are said to suffer from “narcissistic personality disorder.”

Among the symptoms: a grandiose sense of self importance, recurrent fantasies of unlimited success and power, a haughty indifference to criticism.

That sounds a bit like Herbie. But there are some more traditional explanations, an older diagnosis:

Ecclesiastes 1:9–”What has been is what will be, and what has been done is what will be done; and there is nothing new under the, sun.”

Ecclesiastes 1:14–”1 have seen everything that is done under the sun; and behold, all is vanity and a striving after wind.”

©1982 Bruce Locklin

Bruce Locklin, a reporter on leave from the Bergen Record, is investigating aspects of organized crime.