In Judith Berry Griffin’s office on Boston Common, a watercolor called The People Could Fly hangs on the wall. It portrays blacks of every age and size taking to the sky like birds.

As president of ABC: A Better Chance, Inc., Griffin’s job is equally ambitious–to help minority children soar into high achievers at the nation’s premier college preparatory schools. Each year, her corporation places more than 300 inner city youths in private schools that are willing to subsidize black academic promise to the tune of $12 million in scholarships.

“We play a critical role in these children’s lives,” said Griffin, her dark eyes shining. “Every child, if he wants to live fully in America, has to step into the mainstream. Our goal is to help him jump into the river and get to the other side as quickly as he can.”

But she and others who have sat behind her desk have been accused of perpetrating a brain drain and other offenses on the black community, sometimes by the very students ABC sought to help.

“They were really training you to be black WASPs–that mentality is alive and well at Exeter, Choate, Deerfield and Nightingale-Bamford,” said Demetria Royals, a 1973 ABC graduate of the Putney School in Vermont. “There are black kids who come out of these schools saying, ‘I want to get as far away from the ghetto as I can.’”

In his book, “Best Intentions,” writer Robert Sam Anson charged ABC with generating “cultural schizophrenia.” The book traces the life and death of Edmund Perry, an ABC student from Harlem who was shot to death by police in 1985 only weeks after graduating with honors from Phillips Exeter, one of the nation’s most prestigious prep schools.

For 26 years, ABC has provided an elite passport to opportunity to more than 7,000 minority youths, mostly black and poor, from back-roads, barrios, reservations and public housing projects. Transporting them to private institutions that educate congressmen and presidents, like Choate and Phillips Exeter, ABC has been their ticket from poverty and powerlessness to access and achievement.

According to one ABC study, the results have been overwhelmingly successful with nearly 99 percent entering college.

Today, alumni are doctors, lawyers, scientists. Among them are: Jesse Spikes, a Rhodes Scholar from rural Georgia; Tracy Chapman, a Grammy Award-winning folk singer from the slums of Cleveland; and Francisco Borges, the Connecticut State Treasurer who grew up in New Haven’s impoverished Hill section.

In interviews with 40 alumni, half looked on ABC as an undisputed savior: “If it hadn’t been for ABC I would still be in South Bronx right now, somewhere probably dealing drugs,” said Quinn Eli, a writer and 1980 ABC graduate of the Promfet School in Connecticut.

But others puzzle over the hand ABC played in their destiny. “It was a very difficult experience,” said Janice Simpson, an assistant bureau chief for Time Magazine. She left Harlem in 1965 to attend the Wayneflete School in Portland, Maine.

“It changed me and was painful in ways that I don’t even know how to express,” she said. “I am a different kind of person because of it.”

ABC is one of the few survivors of the Great Society educational programs, thriving long after that era’s idealism and outpouring of federal funds faded.

Yet ABC has been on the verge of self-destruction more than a few times as its administrators and ruling board of directors battled over its identity and mission. Would ABC serve as an aid program for at-risk, underprivileged children or would it operate as a high-gloss minority recruiting firm for preparatory schools in search of the best black brains?

The ABC story warrants telling as the nation approaches the minority-dominated workforce of the 21st century; and educators seek ways to boost black college enrollment and rescue minority children trapped in a permanent underclass far from opportunity’s reach.

Last year, ABC chose 338 new students from 2,042 applicants. A total of 1,114 students were enrolled in 74 independent boarding schools, 52 day and 24 selected public schools.

ABC began in 1963, nearly 10 years after Brown vs. The Topeka Board of Education outlawed public school segregation. While the nation’s public schools moved reluctantly toward desegregation, a group of 23 New England prep school headmasters, spurred by a sense of noblesse oblige, moved speedily to open their doors to blacks. Howard Jones, then president of Northfield School in Massachusetts, a pioneer in admitting minorities, headed the group. They called themselves the Independent Schools Talent Search (ISTS). Their mission: “to create Negro leadership necessary if integration is ever to be achieved.”

“It was the Civil Rights movement and there was a fairly pervasive feeling that everybody had a role to play, even somebody at a sheltered, privileged private school,” said William M. Berkeley, then admissions director at Solebury School, among the first to accept ABC students. ” didn’t get on a bus and go down south. I didn’t teach at an inner city school. ABC was a pretty safe way of getting involved.”

Meanwhile at Dartmouth College, President John Sloan Dickey, frustrated with efforts to recruit blacks for Dartmouth, was convinced that improved secondary education was the key.

Dickey and Jones joined forces. Dickey designed Project: A Better Chance, an eight-week remedial summer program for boys at Dartmouth, funded by $150,000 from the Rockefeller Foundation. In the fall, ISTS would reward those who completed it successfully with full scholarships to prep school.

To recruit students, ISTS lured a young Harvard graduate, Jim Simmons, from the National Scholarship and Service Fund for Negro Students.

Simmons quickly spun a national network of school teachers, guidance counselors, ministers and community leaders who scouted inner cities and rural counties for promising male students.

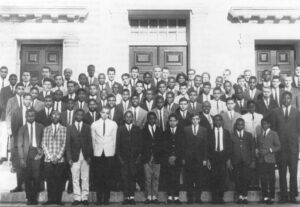

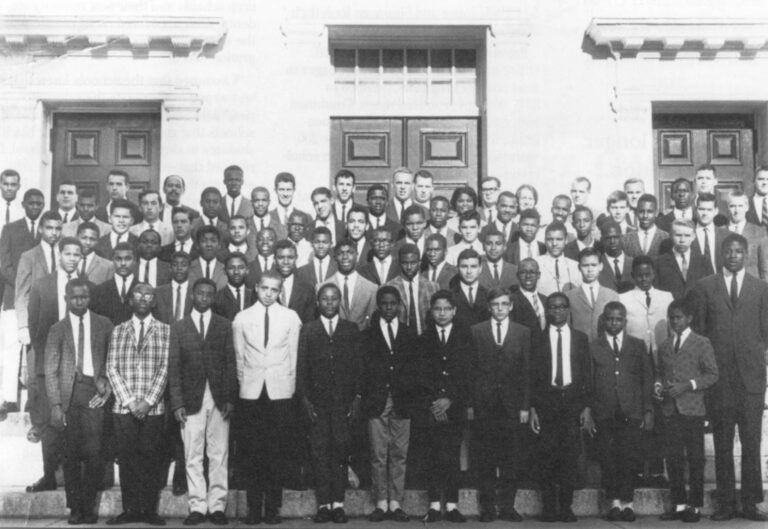

They found 55 boys–44 blacks, five Puerto Ricans, three whites, two Chinese and one Native American, ages 13 to 15. Most had good grades but low standardized test scores. Some were clear risks. They seemed motivated but were questionable achievers. Eighty percent came from families with annual incomes of $7,000 or less.

That summer, boys accustomed to running free in fields and city streets adhered to hours of intensive math, English, reading and a three-hour evening study hall. They received strict social grooming: suit coats and ties in class; white linen napkins and salad forks at meals.

“We had a meeting in the dormitory that first night,” recalled Charles Dey, then a Dartmouth associate dean whom Dickey put in charge of the summer program. “I said, ‘I’m holding your return trip tickets and if you are smart, you’ll take them and return home.’ In effect, I said you are giving up your family, friends and you are being asked to go into a white world with lots of unknown people who don’t like you or want you.”

Not everyone took the proposition seriously.

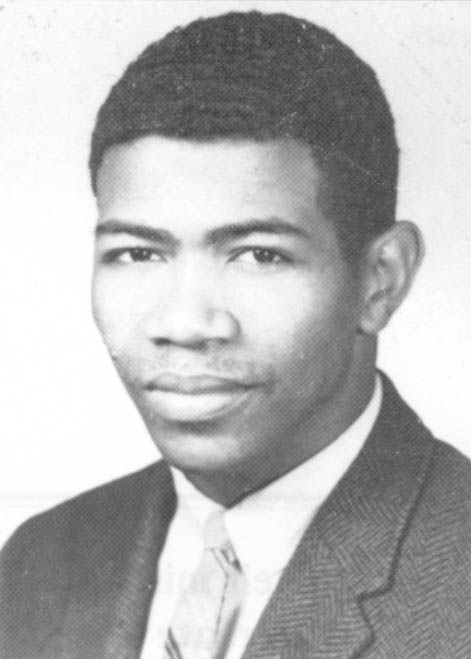

“I almost didn’t make it. Here I was a kid from Roxbury and these white people were telling me I was going to a fancy school and then to college. I just didn’t believe it so I was having trouble applying myself,” said Robert Johnson, a 1967 graduate of the Commonwealth School and a Boston attorney.

“I wouldn’t do the work and kept cutting up,” he related. “Then one night one of the tutors took me aside and said, ‘This is for real man and you are blowing it.’ I straightened up after that.”

That fall, 49 boys were chosen to attend Concord, Deerfield, Groton and other schools on full scholarship.

In 1965, Jones and Simmons took their fledgling mission to Washington.

President Johnson’s newly created Office of Economic Opportunity, eager to fund poverty programs, pumped in $377,000 and promised more. Combined with a second Rockefeller Foundation grant, there was enough money for 200 more students to attend schools on scholarship.

Government funding for independent school students was a new phenomenon and it enticed 48 more private schools to join ISTS/ABC, more than tripling membership.

But with the federal money came strict income stipulations. Eligible students had to be from “disadvantaged or underprivileged” families living at or below the federal poverty level. While the majority of the first group had been poor, poverty had not been a requirement. Now it was.

“A number of us welcomed the entrance of the OEO money on the scene because it made the emphasis on poor kids official,” said Berkeley, who succeeded Simmons as ISTS executive director in 1967.

Wary of dependence on federal funds, ISTS set up a development office. Other changes came as well.

At the insistence of girls schools that joined ISTS, a summer program for 50 girls began at Mt. Holyoke College in Massachusetts.

ISTS/ABC hired more staff, mostly young, white idealists who leaped into the program as their chance to be part of the new integrated America as President Kennedy had urged them to do before his death.

“We thought we were going to change the world,” recalled Gina B. Tangney, ISTS associate director from 1965 to 1967. A Wyoming native who attended Sarah Lawrence College, she found herself shuttling to the South Bronx to pick up students.

While the battle to desegregate the nation’s public schools played out violently and publicly, private school integration proceeded quietly but no less painfully. Peter Hans Sauer, hired by ISTS to investigate problems between the prep schools and their new minority students, soon uncovered racist practices at the very institutions that had touted integration efforts.

“I assumed that the schools knew that it was wrong to segregate their dormitories,” said Sauer. “There were a couple of schools that automatically put their black students in single rooms. At one school, I realized that every single one of the ABC students there was in a single room. I felt that was wrong. They were using government money to segregate these kids.”

Carolyn Barkley, a 1969 graduate of a Pennsylvania Quaker School said she learned years later at a reunion that “the school had sent my roommate’s parents a letter asking their permission for her to room with a black student.” Other students met with teachers who had stereotypically low expectations of minorities.

“Government-funded black students–If you were a headmaster, it was just an amazing, fantastic deal, which was one of the weaknesses of the program,” said Sauer.

“It was so seductive for the schools to participate that it was too easy for them to overlook the true difficulties that were involved in integrating: a school in a responsible way.”

When confronted, schools warned IST’S to stay out of their internal affairs, Sauer said. After a year he quit in frustration.

The program’s first failures surfaced among Native Americans. Almost half had dropped out of the program in the first 10 years, said George Perry, former ISTS director of programs, who conducted one, of the first student attitude studies.

“My culture and values were so different that I couldn’t get into the rat race of always competing. The people were almost plotting a graph to the right law firm,” said Robert Abrahms, a Seneca Indian who graduated from the St. Paul School in Concord, Connecticut. He has worked as a security guard for the last 13 years.

But with successes outweighing problems, the program grew. With an infusion of $1.6 million from OEO in 1966, ISTS accepted 400 more students. To stretch the funds as far as possible, each student received a $1,500 federal scholarship each year and the school paid the remaining tuition, plus paying the full costs for one other minority student.

The OEO money paid for more ABC summer programs at Carlton College in Minnesota, Amherst and Williams colleges in Massachusetts and Duke University in North Carolina.

The national recruiting network grew rapidly. More students applied. But schools were saturated, their scholarship funds exhausted. Trustees complained about setting aside large sums of money for blacks, said a former administrator.

In hopes of removing more students from poor inner city or rural, segregated schools, Dey designed a plan to send youths to reputable public schools in well-to-do communities.

He organized a citizens group, headed by the chairwoman of the Hanover, New Hampshire, school board. It raised money locally to purchase and run an “ABC House” where 10 students would live. Next he hired as resident director, Thomas M. Mikula, a stern-faced mathematics teacher from Phillips Academy, who had taught in the summer program.

Headmasters at traditional boarding schools called the idea preposterous.

“Anybody would be pessimistic about going into a community like Hanover and bringing in a bunch of black kids, starting a house and sending them to the local public high school,” said Mikula.

In fall 1966, Jesse Spikes from Georgia and Beverly Love from Alabama were among the first eight residents at the Hanover ABC House.

Spikes and others agonized over the isolation and rebelled against Mikula’s disciplined study requirements. In a basement powwow, unknown to Mikula, the boys plotted not to return after Christmas break.

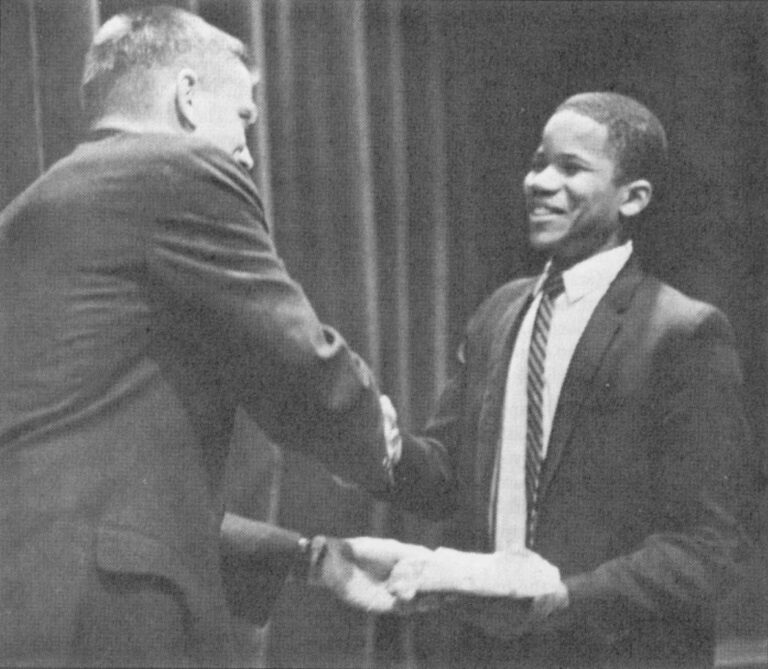

But they did. Spikes graduated from Hanover High School in 1968, attended Dartmouth and in 1972 became ABC’s first Rhodes Scholar. He is now an attorney in Atlanta. Love is now a physician in Montgomery, Alabama.

Dey dispatched Mikula to small cities across the country to launch ABC Public School Programs. First he drummed up support from Dartmouth alumni in the targeted cities, helping them form citizens groups to muster clout and raised money, as much as $100,000 annually to run the house.

Opposition was common. Residents flocked to city council meetings to block ABC’s requests for zoning clearance or to waive school tuition. One irate citizen showed up with a shotgun, Mikula recalled.

“They would never bring up race,” Mikula said. “It was not that there were going to be ten black kids living next door that bothered them. It was zoning, or increased traffic or property values dropping because of higher density. But underneath, I knew the whole issue of race was there.”

In eight years, Mikula set up 36 ABC Houses from California to Connecticut.

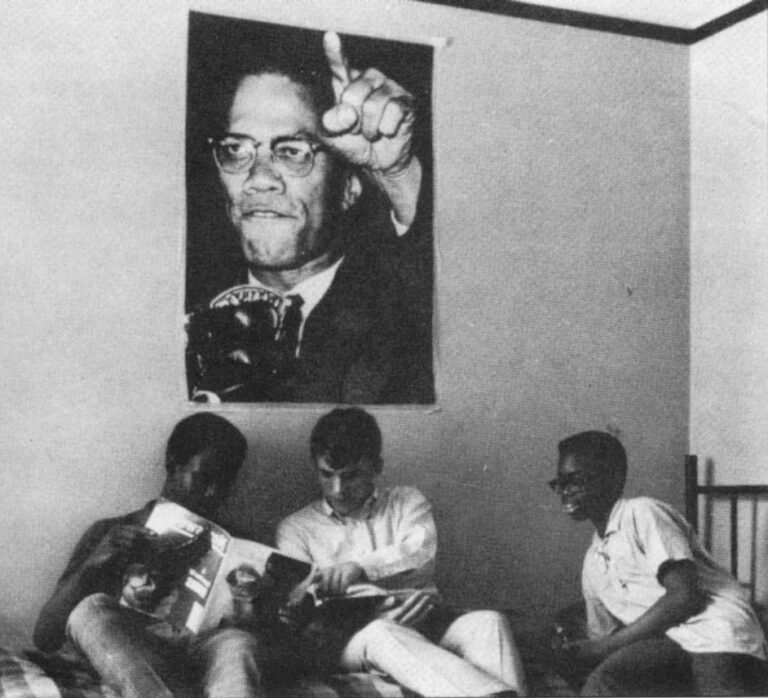

Students, once the instruments of integration for the elite, brought the battles of the Black Power movement to prep school campuses in 1969. They demanded black courses in the curriculum and black organizations. They wore afros.

“The critical mass of black kids reached the point where they had their first black tables at lunch,” said Berkeley. “Headmasters would call and say, ‘Integration isn’t working at our school. Why did we get involved with ABC anyway?’ “

Great Society idealism disintegrated. OHO abruptly cut ISTS/ABC funding as President Johnson funneled more money into the Vietnam War. Parents and activists questioned whether youths would return to their communities to provide leadership. Others labeled the program a drain of the black community’s brightest minds.

“We caught a lot of that rape of the black community criticism from the activists,” said Edouard Plummer, a teacher at Wadleigh Junior High School in Harlem, who has recruited nearly 300 ABC students in 24 years. “But a lot of those kids who didn’t go to ABC and could have, are in prison today. That’s no exaggeration. I wasn’t worried about my kids returning to Harlem.”

In 1971, ISTS/ABC and the Public School Program merged as A Better Chance, Inc. A headquarters office was located in Boston. A maturing ABC analyzed more closely the radical intervention it made into children’s lives.

Early studies showed that nearly 99 percent of the ABC students had gone on to college compared with 50 percent of a control group with similar standardized test scores and socioeconomic status. Twenty-one percent were accepted to schools classified as highly selective, such as Dartmouth and Harvard.

“We were playing God with the lives of kids we didn’t even know and that’s why our emphasis on kids who represented some degree of risk meant a lot to us,” said Berkeley.

In September 1972, with the aid of grants totaling more than $1 million from New York Model Cities Administration and the Upward Bound Program, ABC accepted 626 new students, its record year.

Admission standards became the program’s next controversy, when Berkeley called for a 3-year period of lower admissions standards. He believed them necessary if ABC was to accept poor kids sponsored by the federal Model Cities money. But ABC’s board of directors balked at lower standards, demanding selection of candidates with clear academic ability.

“Schools were quitting ABC or threatening to quit because the caliber of the students was getting worse,” said William M. Boyd II, then director of the Educational Policy Center and an ABC board member from 1969 to 1973.

“There were people within the board and the ABC staff who said that if we raised standards then we wouldn’t be serving the most disadvantaged,” he said. “People were equating economic disadvantage with intellectual disadvantage. I disagree with that. Some of the kids who have come out of dire poverty are the superstars.”

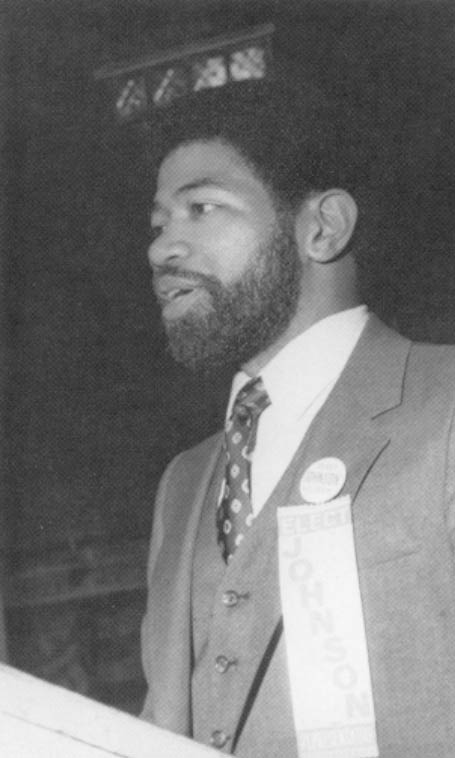

Boyd’s support of higher admissions standards appealed to the board. When Berkeley resigned as ABC executive director in 1974, Boyd, who had been the first black to attend Deerfield Academy in 1956, seemed a natural successor.

He immediately raised admissions standards much to the board’s relief. “Emphasis was placed on student ability rather than degree of poverty,” according to one ABC report.

Boyd implemented a partial scholarship program, in which parents of ABC students paid a portion of tuition. The black middle class had grown considerably and occasionally students applied to ABC who needed no scholarship, he said.

“Two-school teacher families would tell us they could pay something, but not $6,000 a year. We wanted to include that kind of kid,” said Boyd. “It wasn’t that we were trying to get brighter kids, but more middle class kids who could go on a partial scholarship.”

By 1974, the summer programs, once an ABC mainstay, had been reduced to three-day seminars at local colleges. Students came better prepared and schools were more experienced at helping them.

When Boyd left in 1981, twenty-three independent day schools had joined, bringing the number of ABC member schools to 150. The residential Public School Programs had become an albatross, triggering ABC budget deficits of more than $100,000. That year, ABC’s 12 regional offices recruited 515 students.

Under Griffin, a tenacious former staffer at the U.S. Department of Education who became ABC head in 1982, the development office matured, securing more than $l million annually from corporations and foundations from CitiCorp to Standard Oil Company. The money also began flowing from alumni, increasing from $247 in 1983, to $14,168 in 1987 as ABC graduates climbed into corporate and middle-class America.

ABC, the pioneer of immersion schooling programs, now faces new competition.

In recent years, Prep for Prep and the Oliver Program, both in New York City, The Link in Chicago and Alliance in Los Angeles have emerged with missions similar to ABC’s. Competing for the same corporate and foundations grants, they pitch on-going academic, social, vocational and emotional preparation and support as an edge over ABC.

Today ABC also competes with public schools for private giving. Philanthropists facing mounting pressure to support programs to better the nation’s ailing public school system, find elite alternatives like ABC less attractive. Said John Brown, ABC director of development, “Ideas like ABC just don’t grab the imagination the way they did 20 years ago.”

The 1980s also brought an end to government funding, as the Ford and Reagan administrations phased out Model Cities and other aid programs. In 1984, the ABC board, after much debate, voted that schools would foot the entire tuition bill for ABC students since government scholarship money was no longer available.

That decision gave ABC member schools a stronger voice in student selection. They apparently opted for more middle-class students who could pay a portion of tuition and were better prepared academically than poorer students from inadequate public schools.

“In the early days, the definition of an ABC student was underprivileged and disadvantaged,” said Barbara Booth, director of programs at ABC. “That is no longer the definition. It changed when we stopped getting government funding. Probably today, 40 percent of ABC families pay something toward tuition. They can’t afford much–maybe $100 to $2,000.” Annual tuition can cost from $6,000 for some day-schools to $16,000 at Choate and other boarding schools.

At least 30 percent of ABC students are on welfare, Griffin said. Or Students may come from families earning $30,000 to $40,000 a year. But such income spreads thin in three and four children households in expensive metropolitan areas like New York City and Chicago.

But alumni, who assist in promoting ABC, say many of today’s recruits bear little resemblance to the inner city youths ABC rescued from dire poverty in the 1960s and 1970s when government money was abundant.

Three years ago, “I volunteered to interview prospective ABC students and it seemed to me that at least half of them were from middle-class families,” said Edna Triplett, a 1979 graduate of Lawrence Academy.

This departure from its early mission troubles many who believe ABC is the only chance for talented youths to climb out of the underclass.

“They were not kids like I was with nine brothers and sisters growing up in the ghetto on the west side of Chicago,” Triplett said. “Who is going to help the kids who are like I was?”

©1990 Charlise Lyles

Charlise Lyles, a graduate of the ABC program, is examining its impact in the last 25 years. She is a reporter for The Virginian Pilot and Ledger-Star.