Ridgefield, CT-The cute Puerto Rican girl from the Bronx perched atop her bunk bed in a boarding house and pondered her ambivalence toward this affluent, mostly white town where she attends school.

Ana Negron, 17, delighted in the academically challenging school. She adored the local host family that welcomes her on weekends. She abhorred the prank telephone callers who nearly four years ago threatened: “All “n…..”s die.”

“When I first came here for some reason, I didn’t really notice that everyone is white,” said Negron, who hopes going to Ridgefield High will help fulfill her dream to become a psychologist. “I guess I saw coming here as an academic opportunity to go to a better high school and to get into a good college so that’s all I was thinking about.”

“But we’ve had really bad experiences, especially the phone calls,” Negron continued, her voice carrying the cadence of hip street vernacular. “I didn’t think that I would have to take all of that just because of my skin color. I started to just go back home after the phone calls. Then I realized, hey, I can’t always run away from my problems. I called my mother and told her I was staying.”

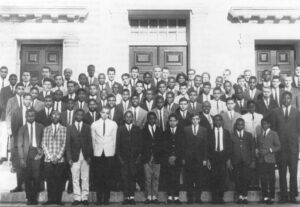

Negron and her five roommates at the Ridgefield ABC House are among 180 gifted minority students mostly from New York City and New Jersey, who attend selected public high schools in 24 affluent New England and Midwestern towns. They are enrolled in ABC-A Better Chance Inc.’s Public School Programs.

Since 1964, the primary mission of ABC, a private non-profit Boston-based agency, has been placement of disadvantaged minority youth in the nation’s premier private preparatory schools. In 1966, ABC developed the public school concept to pull more academically promising students from inadequate inner city schools.

In each town, volunteers initiate. organize and operate the program. They assume full responsibility for the youths’ education and welfare. First the volunteers must obtain a tuition waiver from the local high school so the non-resident ABC students can attend.

Then it must raise up to $70,000 annually to operate the ABC House where students live with a “resident director” and tutors. Expenses include purchase of a home to be used as the dormitory, food, utilities, a cook. ABC headquarters offers no financial assistance to the towns.

Its major role is to approve the school’s academic quality and to recruit the students who participate in the program. Most are in the top 10 percent of their junior high school. In pursuit of a superior education, they exchange family and urban life to learn and live in villages where they feel as alien as an extra terrestrial.

Like most pre-revolutionary settlements along Connecticut’s “gold coast,” Ridgefield is a fortress of white flight: Middle class Italian-Americans, landed WASP aristocrats, and corporate CEO’s. According to a 1986 census report, only 100 blacks were amongst the town’s 21,000 inhabitants. Blacks and Hispanics are so few, said one businessman, that employers bus them in from nearby Stamford to fill menial jobs.

Nestled in the opulent, green hills of Fairfield County where income exceeds $18,000 per capita, Ridgefield is the twelfth most wealthy municipality in the state. Pillared mansions and horse ranches line the landscape. Townspeople joke that the rich even go to jail here, recalling Rev. Jung Sun Moon’s stay at a nearby federal prison.

In 1984, a faction of local progressives agreed that Ridgefield was too wealthy and too white for its own good. They formed the Ridgefield ABC Board and launched a battle to build a program here. It pitted newcomers against townies, old against young, and ignorant against sophisticated.

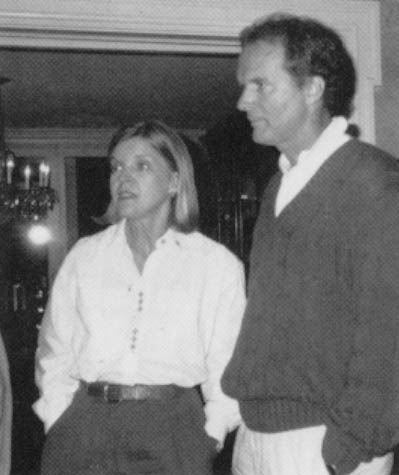

“This is a very homogeneous place. We’ve got people in this town who have never seen a black person,” said Phillip Lodewick, president of a national leasing firm and vice-chairman of the Ridgefield ABC Board. “This program allows for a cross-pollination of cultures. It’s enrichment for the girls. It’s enrichment for the town of Ridgefield. Many people here do not perceive it that way, but that’s what it is.”

Lodewick and others made an uncommon commitment to overcome racial and cultural ignorance, albeit at their convenience and under their control. Amongst the well-to-do, such reaching across class, cultural and racial barriers had gone out of style a decade ago.

“Let’s face it, six kids in a school isn’t exactly integration. But at least my kids will have a chance to know a black or Hispanic person,” said Sharon Dornfeld, an attorney and ABC Board member. “We believe in equal education. We have an excellent school here. Why shouldn’t others use it?”

For the girls, the program has stirred the exhilaration of academic and intellectual challenge. These children of immigrants and the underclass see ABC as their one chance to make real dreams of becoming doctors, executives and lawyers. “I know if I were in New York City 1 would be cutting classes, partying right now and still getting A’s,” said Negron. “There is more competition here and you really have to study.”

But at times, they suspect that they are cultural specimens imported to satisfy the curiosity and assuage the guilt of the privileged. “I feel comfortable here, but sometimes I wonder if people only want to be my friend at school because I am an ABC girl and they feel sorry for me,” said Carlina Santos, 17, also from the Bronx.

Said Diana Ward, a businesswoman who volunteered to take girls to her home on weekends, “I don’t feel guilty about what I have. We worked very hard for it. But we do want to share it with these very deserving young ladies.”

The Ridgefield program is the newest ABC public school project. It came to be a decade after ABC administrator Tom Mikula and a surge of upper class activism produced 36 Public School Programs from Longmeadow, Mass., to Appleton, Wis. Enthusiasm died in the 1980s and a dozen programs folded.

But the seven programs in Connecticut never faltered. Among them was the Public School Program in New Canaan, about six miles from Ridgefield. For 16 years, New Canaanites, the wealthiest residents in the state whose per capita income exceeds $37,000, have lavished their program for boys with philanthropy and affection.

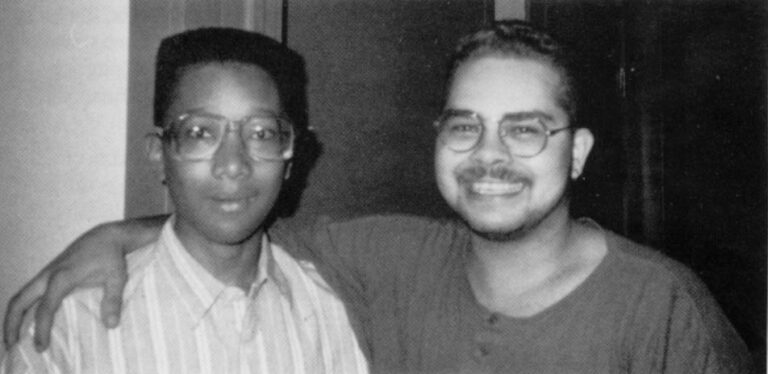

One night at dinner, the boys at the New Canaan ABC House suggested to resident director Steve Blumenthal that starting an ABC program in Ridgefield for girls “was a great idea because it would give us some black girls to date,” recalled ABC alumnus Bernie Haynesworth, then 17.

Blumenthal, school teacher and activist, jumped on the chance to help more needy kids.

To that cause, he marshaled an eclectic assortment of Ridgefield’s good Samaritans, graying hippies and kinder, gentler Republicans. They included Wulf Polonious, a German-born pharmaceutical executive who once led fund-raisers for a Brazilian leper colony; Dornfeld, who was a veteran of Vietnam anti-war protests; and Bob Jones, a jazz impresario.

Blumenthal invited them and a dozen others to dine with the eight students at the New Canaan ABC House. Each boy recounted his story: A deprived upbringing in the streets and the undaunted quest for a good education that led him to ABC.

Haynesworth told the saddest story.

“I told them how my older brother and I had made a pact not to get involved with drugs and to make something out of ourselves,” recalled the softspoken graduate of Wesleyan College.

“I kept my end of the deal. But Raymond, he didn’t make it,” Haynesworth said. “He committed suicide while I was up at New Canaan. He jumped off the roof of this building. I think it was drugs–cocaine. He died in December two days before my birthday. He was 19.”

Haynesworth’s will to succeed as an ABC student despite personal tragedy galvanized the group. Three months later, they formed the Ridgefield ABC board, to organize and operate the program, and raise funds.

The newly formed board’s first step was to obtain a tuition waiver ($6,149 per pupil) that would allow the ABC students to attend Ridgefield High, since they were technically non-residents.

“At every meeting we went to, someone stood up and said, ‘Why are we doing this? It’s a burden to the taxpayer. It’s fine if you want to do it. But don’t charge us,’” said Diana Ward, who was also school board chairwoman. “I would stand up and refute that, saying that every time a student entered school didn’t mean an increase in the school budget.”

To the ABC Board’s surprise, the nine-member school board approved the request unanimously and gave the program its blessing.

The Friends of Ridgefield, a fledgling taxpayer lobby, clamored when the board won tax-exempt status that later freed the ABC house from property taxes.

“I have very strong objections to the establishment of a tax-exempt organization,” said one resident who asked not to be named.

“I live in Fairfield County, a very inflated real estate market. Not everyone is rich. I want them (ABC) to pay taxes ($17.74 per $1,000 of assessed value) like everyone else. A family would have to pay taxes to live in that house. Our taxes just keep going up. The pie gets bigger. If you subtract one piece, you’ve got to make it up somewhere else.”

Opposition mounted when the board began searching for a house to serve as the ABC dormitory. “We encountered the classic ‘not in my neighborhood,’” recalled Dornfeld, who volunteered legal services to the effort to find a home.

The Hanneman House, a historic home conveniently located in the center of town, seemed ideal. A city-owned property under the jurisdiction of the Department of Parks and Recreation, it had been rented for years.

The ABC board requested a 10-year lease on the house and offered a $95,000 renovation. But officials of the Parks Department said a soon-to-be-unveiled plan to convert the home to senior citizen apartments was top priority. Park Department officials asked the town’s board of Selectmen to decide.

After a fiery public meeting that drew scores of residents, the Selectmen called for a town referendum. Citizen votes on the annual school and town budget were common. But other issues rarely went to the voters.

The opinion-seeking ballot asked voters whether the Hanneman House should be leased to ABC or converted to senior apartments.

Senior groups campaigned against ABC, contending that young outsiders would use the home at the expense of the town’s needy elders. Eleven days before the election, the ABC board pleaded its cause in a half-page ad in the Ridgefield Press.

On April 26 1986, mini-vans shuttled the elderly to and from the polls all day. The issue drew 1,792 voters. The town has 12,792 registered voters, but in referendums, all adult citizens may vote. ABC lost by only 56 votes: 924 in favor of senior apartments and 868 for ABC.

To this day, the plan for senior citizen apartments has yet to be implemented. Parks officials said a sewer moratorium halted the project.

“They were all very careful about it. At all the town meetings we had, no one would come out and say they were scared of these black kids from the city,” said Christine Lodewick, current chair-woman the Ridgefield ABC Board. “Thank God, we weren’t trying to get an ABC House for black males. They would have thought that boys would rape every white girl in sight.”

Undaunted, the board scouted for a new location. About $75,000 raised from board members, churches and businesses, including a $20,000 loan from Blumenthal, provided enough for a house downpayment.

The successful fund-raising efforts signaled town approval, yet the “not in my neighborhood” sentiment continued.

A large Victorian house on Gilbert Street was the board’s next target. The board made an offer to the seller. Through a newspaper ad, the board then invited a dozen Gilbert Street residents to explain the new project in the neighborhood.

“They went universally nuts,” recalled Dornfeld. “They figured we were having kids in from the South Bronx for the sole purpose of selling huge quantities of drugs to their children and to steal from their houses.”

The seller rejected the board’s offer of $350,000. Gilbert Street was calm again. ABC looked elsewhere.

Board Members found 32 Fairview Ave., a $325,000 duplex that could easily be converted to a one-family. This time the board decided against a neighborhood meeting.

“It was sneaky the way they did it. I look up and there it is in the newspaper that they have bought a house on my street,” said Earl H. Sturges, an 80-year-old town resident, glaring at 32 Fairview from his backyard. “My feeling was that it would devalue property because this is not the proper place for a boarding house.”

“Now I never see or hear those girls. But that porch is within six feet of my property line,” he said shaking a gnarled finger at the grass.

Sturges hired a lawyer and summoned the ABC board to a meeting for an explanation. Two dozen neighbors organized in opposition.

But Sturges’ group could do nothing to halt the purchase. The board’s final hurdle was a zoning variance to convert the home to one unit. It was denied on appeal. ABC moved in anyway.

By the summer of 1987, broad town support was evident when time came to renovate and furnish the home. Carpenters, wallpaper hangers, painters, plumbers and electricians donated services. Bunk beds, computers, typewriters, dining tables, sofas, fancy draperies, quilts, dishes, a microwave and refrigerator also were given to complete the residence.

In late August, six slight girls from New York City, recruited by ABC headquarters, arrived at the house. They were oblivious to the battle that had gone before them.

The first months were difficult. On her second day here, Santos was struck accidentally by a car and received 12 stitches for a gashed leg. “When I was in the back of the ambulance I just kept thinking if I had stayed in New York this would never have happened. My mother told me to leave, come home,” recalled Santos. “I said ‘no, I want to stick it out.’”

Lamented Dornfeld, “They didn’t know how to walk on streets with no sidewalks. Everyday the board learns something new that we can do to ease the adjustment.”

After five months, one student, who did poorly academically, left the program. She denounced the town in one of many newspaper articles that have chronicled the program’s progress.

“’I’m not saying there’s anything bad about it, but the people here are-I don’t know-just unaware,’” Simone Page-Janello,15, was quoted as saying. “’In their hearts they try to be nice, but they are not aware of what good things other cultures can bring you. This school is so good academically, but I think I’m one up on them on the cultural scene.’”

Three years have passed since the girls received the threatening telephone calls. Neighbors who say they remain opposed to city youths being transplanted to their block, can’t resist waving when they see the girls waiting for the school bus.

“Me girls are not like I thought they would be,” conceded Patricia Ligos, who lives down the street from the ABC House.

And when they arrive at Ridgefield High School, where they are among eight minorities in a student body of 1,294, the cafeteria bulletin board no longer displays watermelon jokes.

Their academic performance has been stellar. The first group of girls made the honor roll three years straight. Last June, three were graduated and headed to Georgetown University, Vassar College and University of Minnesota. In September, three new ABC students replaced them.

Still lessons in pride and prejudice, class and culture are as much a part of their curriculum as math and science.

On a recent afternoon, Lizzette Charles, a tall thin girl from Brooklyn, moped into a bedroom at the ABC House. Dejection darkened her almond-shaped eyes.

“My teacher told this boy to pick ten people to be on a team for a special project,” the 15-year-old pouted. “I raised my hand, it was right in his face. He counted one, two, three and skipped right over me. The whole class was waiting for him to pick me. He didn’t even look at me.”

Said Elizabeth Arnethe, who teaches American Studies at Ridgefield High, “In my class, the girls talked about what a culture shock it is coming to Ridgefield. It helped the kids here to see somebody of another race as a human being. These girls had to work very hard to go beyond any stereotypes and I think they did it because they are very decent, very dignified young women who have tremendous moral fortitude.”

The girls are growing up fast as they deal with the unique pressures of the program.

At times, they are embarrassed by the board’s endless efforts to raise funds. Annual expenses total $70,000: including $35,000 mortgage, $8,000 food, $3,650 utilities, $7,000 cook’s salary. One anonymous donor gave $25,000 last year.

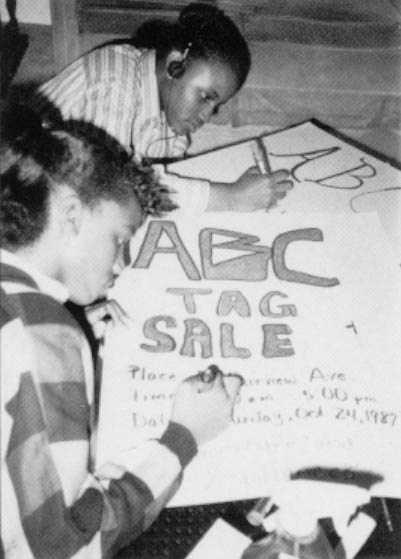

To drum up other support, the girls make occasional appearances before churches, businesses, parades, the Rotary and White Lions clubs. Their classmates donate money from school organizations. At least twice monthly, the girls’ picture appears in the town newspaper, with articles announcing yet another fund-raiser or the program’s financial woes.

“We feel like the UNICEF kids or something with our picture always in the newspaper begging for money,” said Santos. “Sometimes I get the feeling people think our families are starving and we take the money home to New York to feed them.”

Negron chimed in, “And I hate it when they say the ABC girls need this or that. I’m not an ABC girl, I’m Ana.”

On the other hand, said Shauna Daniel, a senior from Brooklyn, “I think we all communicate well because we have had so much practice presenting ourselves at fund-raisers and board meetings.”

The girls are grateful to the board members for the ABC opportunity, but annoyed with the amount of power it seems to exercise over their lives in Ridgefield. Their major complaint: They yearn to go home to the city to visit friends and family more than the four holidays that the board currently allows.

“They have it set in their minds that once we decided to come here, our lives in New York would completely drop. They think, ‘Connecticut is your home now,’” said Santos.

Robert Cox, a board member and former resident director at the ABC House, agreed: “One of the things that the girls have encountered from the board is the vague notion that they are being saved from the city.”

“The girls would like to spend time with their families. This is not a bad thing,” said Cox. “They are simply making an honest effort to do what any kid wants to do–sustain the most important relationships of their lives. It is important for us to support the girls in their efforts to do this.”

To fill in family affection that the girls are missing, each weekend locals volunteer as host families, sharing their home life with the girls.

“I am very close to my host family. There is not one second in my life where I ever thought they were prejudiced,” said Negron happily.

“My host mother does this because she thought it would be a good experience for her and her family,” she said. “She loves different cultures. She doesn’t treat me special, like an ABC girl. I clean dishes and everything. She treats me like her own daughter.”

©1991 Charlise Lyles

Charlise Lyles, a reporter with the Virginian Pilot and Ledger-Star, is researching the educational experiment, A Better Chance, Inc.