PHILADELPHIA – The monastery’s gray stone mother house stands stoically amid lonesome pine trees and statues of saints. At one time, the Sisters of St. Basil the Great on Fox Chase Road numbered about 150. Today most sisters have quietly retired from the monastery’s college and high school. Others have died and are buried in the nearby cemetery. For decades few women joined the monastery, causing the sisters to worry that their Ukrainian legacy would end with them.

But the collapse of Communism has provided a new source of life for the aging monastery. Recently, the sisters have tapped the resurgence in religious interest in Ukraine by aggressively recruiting young women in hopes of injecting vitality into their community in America. The result is that after 13 years with no new recruits, the sisters imported a half dozen possible nuns and are expecting another four Ukrainian women to arrive shortly.

Like many Catholic religious orders in this country who are facing declining numbers and possible extinction, the Sisters of St. Basil have taken drastic steps in order to try to assure their future. With 69 sisters now attached to St. Basil’s, the average age is 75 years old — above the national norm of 68 years old for all Catholic religious orders. Only one St. Basil sister is under the age of 50. And their most recent entrant into the monastery is a 62-year-old widow.

In the last three decades, religious orders in this country have decreased by more than 50 percent. Some, like the Visitation Sisters in Washington, Illinois and Kentucky have closed. Others, such as the Sisters of Mercy of the Americas and the Dominican Sisters of Hope in New York and Massachusetts have merged. The situation is so dire that the Benedictines in Madison, Wisconsin are welcoming Protestant women in order to keep their small community in existence.

The Sisters of St. Basil have tried to attract American women but there are few who have even heard of the Eastern Rite church, a small ethnic minority in the Roman Catholic family. For decades, St. Basil’s depended on the daughters of Ukrainian immigrants to enter the monastery and carry on its mission. To this day, the sisters maintain their Ukrainian customs and chant half their prayers and liturgies in the mother language.

The demise of the monastery would eliminate a major unifying force in Philadelphia’s dispersed Ukrainian culture.

The sisters’ decision to reach out to Ukraine comes at an extraordinary time as Ukrainian young people are entering religious life at record numbers because so many are eager to live the religion that was denied them for 45 years under Soviet domination. Young women in Ukraine see the sisters’ invitation as a chance to come to America to receive a free education and fulfill their missionary zeal. These women, like Natalia Taraschanska, a 20-year-old who at age 17 decided to give her life to God, display a deep hunger to help other Ukrainians learn religion, a fervor akin to Protestant evangelizing. For some, the trip here is an acknowledged adventure, an opportunity to escape overly protective parents and a country that is economically strapped.

The decision isn’t without its sacrifices, though. Mariana Romanivna, a tall 21-year-old Ukrainian with cascading black hair and blue-gray eyes, gave up prospects of marriage and a family to immigrate to Philadelphia to consider life with the sisters. The women left behind close-knit families and lifelong friends, many of whom they may never see again. They are required to learn English, live in tight quarters and get up early for morning prayers.

While religious orders over the years have tried — and mostly failed — in attracting newcomers, St. Basil’s approach is among the most innovative. Launched in 1911 by three Ukrainian sisters, the Philadelphia province mostly took in orphaned Ukrainian children. The sisters educated them and depended on some to stay on as nuns. Later, the daughters of Americanized Ukrainians became the order’s lifeblood. But now the community has come full circle, adopting young women from Ukraine in hopes that they too will become the order’s future generation of nuns.

“I think it’s rather unique,” said Sister Catherine Bertrand, executive director of the National Religious Vocation Conference, a Catholic organization that oversees recruitment of women to religious life in this country. “I have plenty of reservations in terms of the various reasons why people would chose to come. For very young people it would be more a ticket to the United States than it would necessarily be an entrance into a congregation.”

The sisters acknowledge their investment is an uncertain venture that may not yield a single vowed nun. And in fact by the beginning of the summer, some would decide to return home. Moreover, the spiritual journey to becoming a fully professed nun takes about eight years.

“The community, and personally I, look upon this as an investment into the women’s movement and into the commerce of the Ukraine,” explains St. Basil Provincial, Sister Dorothy Ann Busowski. “And we realize that they all won’t stay. Maybe none of them will stay. But, it’s our contribution to women of the world and to Ukraine.”

The relationship isn’t without tension. In the first year, the sisters have paid out more than $75,000 to educate, house, feed and clothe the Ukrainian women. Some sisters question whether the order is doing more for “the girls” — as the sisters call them— than the “girls” are doing for the order. Some of the nuns have questioned the motivations of the young women who range from 20 to 23 years old. The average woman entering religious orders in this country now is 39 years old.

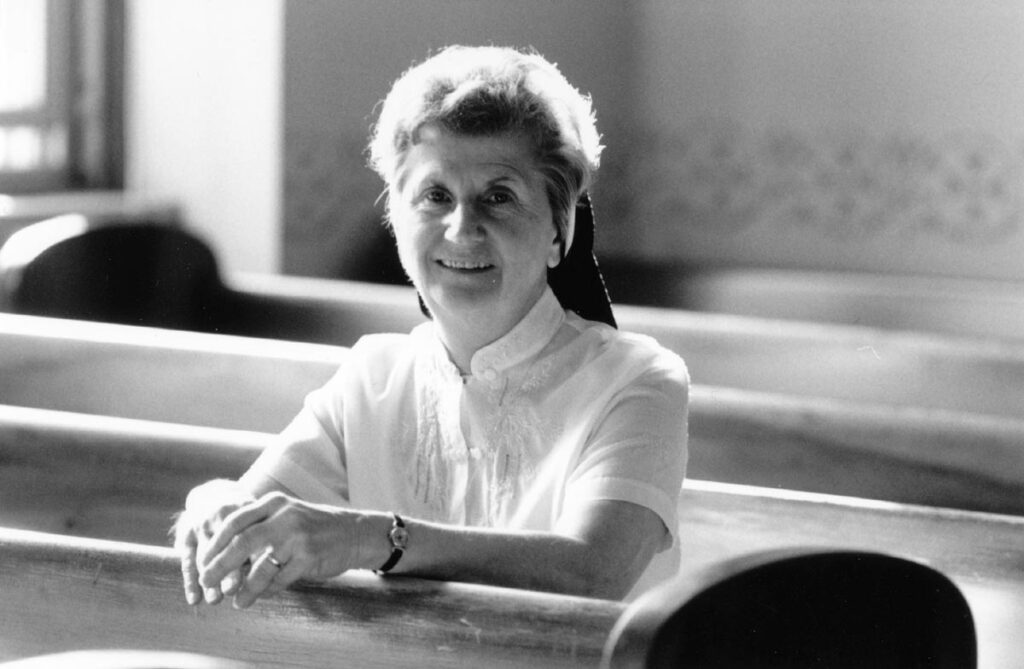

No one was more skeptical about the project than its leader, Busowski, who eight years ago seriously questioned her own religious life. Then, at the age of 51, she was among the order’s youngest members — and also one of the most progressive.

Busowski welcomed the church’s controversial changes in the late 1960s that gave nuns more freedom in what they wore and what jobs they did. She is a feminist in the polite sense of the word; she believes in equality in the church.

A practical, no-nonsense, focused woman, Busowski has shouldered some of the monastery’s biggest responsibilities — running the order’s all-girl high school and overseeing the $3 million project of gutting and renovating the 60- year-old mother house. When the building was finished in 1990, Busowski felt drained. She was disillusioned and hurt when several friends decided to leave religious life, despite her efforts to convince them to stay. When her order asked her to take over as provincial, she knew she had to decline.

Busowski retreated for a year to a priory in Dover, Massachusetts, where she spent hours walking in solitude. She reflected on the religious communities that were closing amid a negative backlash against religious life. She questioned whether her order was progressive enough to survive.

Busowski also was angry that the Roman church didn’t seem to appreciate or understand the Eastern Rite church in which priests can be married and pictures of saints are venerated. Most confused the church with its domineering cousin, the Eastern Orthodox Church. Though there is little difference in theology, the most significant distinction is that Eastern Rites believe in the authority of the pope while the Orthodox do not.

It was a struggle that had plagued Busowski her whole life. As a child growing up in Pittsburgh, she didn’t attend the Roman Catholic school near her home. And when her best friend asked her what religion she was, a young Dorothy tried to describe her Eastern Rite beliefs. When her friend kept insisted that Dorothy was Orthodox, she grew more frustrated.

Even as a nun, she often has had to explain to other Roman Catholic nuns that they are part of the same church. Eastern Rites often feel misunderstood. In the early days of their immigration to America, many were severely misjudged. In the 1880s, Roman Catholic bishops protested the married Eastern Rite priests and many would not allow the newcomers to practice as priests. In 1929, the Vatican ruled that Eastern Rite priests could not be married in America. In Philadelphia, some Catholic nuns warned Catholic students not to attend St. Basil’s Academy because they mistakenly believed the sisters there were Orthodox.

Yet, in recent years it has become almost faddish for Roman Catholics to take up painting icons, sacred symbols used by the eastern church. Busowski felt the Roman Catholics didn’t really understand the eastern spirituality connected with iconography, and worse, their proliferation of icons was tainting the ancient eastern practice.

“It was a struggle for me. I love my heritage. I love my church, and it’s my fault if people don’t know about it,” Busowski explained.

When she returned from her sabbatical, Busowski put some distance between her and the sisters, shuttling for five years between the Basilian province near Pittsburgh and St. Basil’s.

Then, in 1995, her sisters again asked her to become provincial. This time she agreed.

“I never would have become provincial if I thought there was no hope for us,” she said.

One of her first acts after taking office was hanging eight-by-ten portraits of all the previous provincials in the monastery hallway. “We have all the bishops up, why not have all the women up?” she reasoned.

All her predecessors’ photos are in black and white and the all women are wearing black habits — except Busowski. Her picture is in color and she’s wearing a white suit. Was she trying to send a message?

“Maybe subconsciously,” she says. “I think it’s more vanity. I liked the way I looked in that one.”

A slight woman with pale brown hair and fierce blue eyes, she wears her veil for official functions, but rarely in the privacy of the monastery.

“I don’t feel that’s what makes me a sister,” she said, gesturing to her black veil resting on the English settee in her office. “I don’t hide who I am. I’m an outspoken person. (The community) knows what’s in my head.”

Though Busowski had reservations about bringing over young Ukrainian women, she had been given a mission to make it happen.

A few months after her election, Busowski sent Sister Theodosia Lukiw to Ukraine. Officially Lukiw was the acting dean of the Catechetical Pedagogical Institute in Ivano-Frankivs’k, a southwestern city two hours from Lviv. But unofficially, Lukiw was scouting for women interested in becoming sisters in America.

The Ukrainian religious institute consists of about 350 women who are studying Eastern Rite theology so they can teach in parishes and schools. Since independence, public schools have begun hiring qualified religion teachers.

“This was ideal picking grounds,” recalls Lukiw. “These are ambitious young women. We often hear from the girls: I want to do something more with my life.”

When Ukraine gained its independence in 1991, many expected nuns who had gone underground during Communism to come out of hiding. During Communism religious sisters occasionally met in secret, but they didn’t wear habits. Sometimes even their own families didn’t know they were nuns. The women maintained regular jobs and didn’t live together because the authorities were suspicious of groups.

But after independence, many, particularly the older sisters, had a hard time leaving their little apartments, leaving their families. Yet they wanted to be considered religious. Eventually the sisters repossessed their monastery that had been taken by the Soviets, and the women had to relearn monastic life. Perhaps the most jarring part of that culture was responding to the clanging monastery bells that call the nuns to prayer, to liturgy, to eat, to sleep. Ukrainian sisters pray together at least 10 times a day, each instance marked by the bells.

They also wear full habits, long black dresses and veils. The sisters leave the monastery infrequently. If a sister is unable to attend a prayer service, she is required to get the provincial’s approval, a stark contrast to St. Basil’s which has two formal times of prayer each day. At the Philadelphia monastery, a sister can miss services if she is tired or working.

For the 65-year-old American nun, living in the Ukrainian monastery was physically and mentally challenging.

“It was a little bit awkward,” Lukiw says. “Our sisters of the Ukrainian province are running this institute. They are taking vocations into their community and here I’m a Basilian too and I’m saying come with me to the United States. Nobody ever said that it was competition. But I’m sure they were thinking those thoughts.”

Though they had running water in the monastery, hot water was available infrequently. Heat was undependable and city authorities turned off the electricity every Wednesday and Saturday evening to conserve energy.

At night in the monastery, bishops and their guests had to be fed first. The sisters’ meals consisted mostly of breads, soups and some vegetables. Meat, eggs, fish and milk were rare. Sometimes the sisters fared better, particularly if a student couldn’t pay for her classes and offered potatoes, rice or sugar instead.

Of the dozen or so “girls” who Lukiw met with weekly, she became particularly close to Mariana, whose father became a priest after the country’s independence. Mariana shared her father’s love of religion and music. The two sang duets together and he often asked her to critique his poetry and short stories.

“She wasn’t afraid to come to me often and just talk for no reason at all — just to see how I am doing,” Lukiw remembered. “I knew about her boyfriends,” she said. “I told her: ‘You can’t have him on a string. They should know you’re coming to a monastery. As far as I know there were no big tears shed, nothing traumatic.”

Mariana’s friend, Olexandra Pryimych, 21, also called Lesia, was part of the weekly group that met. She had worked in a medical clinic as a secretary and doctor’s assistant after she twice failed to score high enough on the medical school application test to get accepted.

Another member of the group was Tetiana Bober, 21, who as a child moved 12 times because of her father’s job as a priest.

Olexandra Hynpiuk, 21, a pretty blonde-haired woman with a friendly smile was considered a woman with many ideas, a thinker. She learned religion from her grandparents and her parents. After her parents died, Olexandra lived with her older married sister and her family. She entered the institute with visions of teaching religion in the public schools.

Luba Beley, a 23-year-old student from a village outside Ivano-Frankivs’k, was considered the most serious of the group. A quiet, bespectacled woman, she often hung her head in shyness. Luba’s mother was a beautician and her father a chauffeur. She had studied to become a lab technician before she entered the institute.

Lukiw told the women they had to love prayer and they had to be able get along with people from all kinds of backgrounds in order to come to the United States. They also had to have a missionary spirit and be prepared to leave everything they loved behind them to work for the Ukrainian church in America.

Not long after Lukiw formed the group, Busowski went to the Ukraine for the first time. She wanted to see for herself if the women were trying to escape a shaky economy where most people aren’t paid for months at a time and where women choose a husband by the time they are 20 years old or risk having their parents arrange a marriage for them.

Busowski tromped through muddy roads, ventured through small villages and found her way into farmhouses in the Carpathian mountains where she met parents of some of the women.

“I did a complete turn-around big time,” Busowski admits. “I saw that they were deeply spiritual. And I felt the sincerity from them. That’s where I really felt that I wanted to do something for them no matter what their motivation is.”

Several parents wouldn’t give their daughters permission to leave. For other women, the wait to come to America proved to be too long, so they entered the monastery in Ukraine.

“Two of them got married on me,” Lukiw said. “But that’s okay. I should have expected that.” In one case, a woman was extremely devout and committed to coming but her father objected and arranged a marriage with a seminarian. Of the dozen or so women she started with, six emerged as the first group to come to America.

Lukiw remembered telling the women in a sing-song voice: “It’s time to say good-bye to your friends, to your family and to your boyfriends. You have to leave them behind. They just smiled and nobody made a fuss over it.”

Originally the women were to arrive in the United States on the Fourth of July in 1997 and then return to Ukraine the following June in 1998. They were to spend their first year learning about American culture, religious life and the English language. It allowed the women a chance to observe the sisters and the sisters to observe them before either made a commitment. But no decision about formally entering the monastery would be made until the women returned home for the summer.

Not everything went as planned.

In April 1997, three months before they were supposed to arrive in the U.S., the women boarded a train headed for the American Embassy in Kiev. They left at 2:30 p.m. one day and arrived in Kiev at 7 a.m. the next. After standing in line for seven hours, embassy authorities denied their request for religious visas.

Thus began Busowski’s year-long battle with immigration to secure cheaper and less stringent religious worker visas. Finally, Busowski relented in August and the women were given student visas, with the caveat that the monastery spend $3,000 per woman for a 10-week language class — much more than the monastery had budgeted.

On Sept. 26, 1997, all six women were up by 5 a.m. though few actually slept the night before. They drove to the airport in Lviv, about two hours north of the institute. Mariana starred out the back windows of her parents’ car through the darkness and the pouring rain. At the airport, the women stood together with their families, crying and hugging each other. Mariana’s mother offered her daughter last minute instructions: “Do you have everything? Be careful. We love you.”

As the women passed through security, they could still see their families on the other side of the windows. Tetiana’s parents pressed a hand-written message to the glass: “Call when you get there. We love you very much.” As the women lugged their bags to an airport bus that would transport them to the plane, they stopped and kept looking back for as long as they could see their families.

After an hour-and-a-half flight, the women arrived in Warsaw where they had a lay-over until their plane to Newark, N.J. In the airport bathroom, Mariana and Lesia watched in amazement as the water faucets automatically turned on. They stood back for awhile before bravely putting their own hands under the faucets.

On the flight to the United States, few could sleep.

When they arrived in Newark, Natalia acted as the spokeswoman with customs because she knew a little English. On the other side of security, stood Busowski, Lukiw and the two women who would become their surrogate mothers, Sister Paula Jacynyk and Sister Joann Sosler.

A couple hours later, they arrived at the gray and white Mary Martha Inn, a six-bedroom home the sisters purchased as an investment and as a place to house the Ukrainians. Inside, seated around the kitchen table were ‘Little Soul’ dolls, two-foot high figures with faces similar to Cabbage Patch dolls. They were gifts from the sisters.

At lunch the next day at the monastery, the Ukrainian women were faced with the dining room smorgasbord of meats, sweets and a variety of vegetables. “Can I take a little or a lot?” Mariana asked.

One of their first outings was to buy new clothes. Sisters Sosler and Jacynyk took the women to the Franklin Mills mall where the women stood starring at the lights and the vast selection of clothes. There were so many choices they couldn’t make up their minds. In the Ukraine there are no malls and few choices to make.

“I kept trying to hurry them along,” recalled Sosler. “The next thing I know they’re standing in front of a department store window taking their pictures with mannequins in evening gowns.”

Eventually going to the mall would become one of their favorite hobbies, along with shopping at Genuardi food stores and the Dollar Store. They’ve acclimated to America in fairly traditional ways: their favorite food is Domino’s Pizza, they are fascinated with Buffy the Vampire Slayer — although they rely on a sister to translate the television sitcom into Ukrainian. Their English has progressed slowly — much more slowly that the sisters anticipated. None can carry on a conversation in English.

The hardest part about their transition to America, says Lesia, was learning to live together and being separated from their families. The next difficulty was getting up at 5 a.m. to pray at the monastery at 6 a.m. While the American sisters wear little or no makeup and their hair is covered by a veil, the young Ukrainians spend their early morning hours primping in front of a mirror, curling their hair, applying mascara.

At times, the Ukrainian women are distant and reluctant to trust their hosts— a trait the sisters attribute to their having grown up under Communism.

“There’s a difference in mentality,” explains Busowski. “Although we are Ukrainian and our heritage is Ukrainian, we are more Americanized and I think we share more easily than they do. So there is a difficulty in getting them to reveal their true feelings. I think they’re so used to hiding things, you never knew who was going to turn you in.”

In interviews for this article, the women were reluctant to speak openly. They said Communism isn’t really dead in their country, and they fear that someday those in the former Communist party may regain power.

Under the Soviet regime, the women were secretly baptized. And before 1989, most Eastern Rite church services were held in woods or in someone’s basement. After the Berlin Wall fell and the Soviet Union began to lose its grip, Ukrainians started worshipping more openly, but there were still problems.

Natalia attended church with her grandmother, but she always was coerced afterwards, she says.

“I got some problems in school with director,” she says in slow and broken English. “My director ask me: Why are you going to the church?” It wasn’t really allowed.”

She later met a monk from a Basilian monastery who helped get her accepted into the religious institute in Ivano-Frankivs’k. There she studied grammar, Greek, Latin and English. Her best friend, who was a nun, inspired her to consider becoming one too.

Like most of her Ukrainian house mates, Natalia hasn’t decided for certain that she will take religious vows. She knows it’s a big decision. All the women had difficulty articulating —either in English or Ukrainian — why they wanted to become sisters.

Luba, the oldest of the group at 23, says she feels God is calling her to this life, a common answer shared by American women who aspire to become nuns. Like the others, Luba is eager to wear the habit.

“To be a sister, you have to have a habit,” she says in Ukrainian.

Mariana says she wants to become a sister because she has seen people suffer and she wants to help.

“I live with my parents and I know that if I were at home, I would not be able to move far beyond my parent’s wing,” Mariana says in Ukrainian. “So I tell you truthfully that is my reason for being here.”

Since their arrival, Busowski has succeeded in securing three religious worker visas. But lawyers warned that there was still a chance that the women might not get back in the country if they went home.

“They had to make a decision,” Busowski said. “I told them: ‘If you really want to stay, you will have to stay without going back home.'”

In June, the two women who decided to return to Ukraine said their good-byes. They were not ready to make a commitment just yet, they said. One wanted to finish her last year at the religious institute and the other missed her parents. They might return, they said.

That afternoon the community held a prayer service in the chapel for the two women. Only hours earlier, several sisters had gathered around the body of Sister Veronica Hanich in her room in the infirmary. At 88 years old, the sister had fallen in her bedroom and suffered a stroke.

“It was like a double death,” remembers Sosler. “We lost one of our sisters and we were losing two of the girls.”

For Sosler, the Ukrainian women had become her surrogate daughters. She had cared for them for nine months, taking them shopping, helping with their homework, monitoring the incessant phone calls and sorting out the conflicts that arise when six young women have to share a bathroom. It was the closest the 57-year-old Sosler had ever felt to being a mother.

“The group is not the same,” Sosler lamented a few days later. “It seems as if someone is missing,” she said looking around the kitchen. “They miss them. They need to gather together. Some of the ties have been broken.”

The spaces where Natalia and Tetiana had sat were now empty.

Busowski isn’t ready to say she has found the fountain of youth for her order. It’s still too experimental, she says. What she’d like to emphasize is what the young women are doing for the sisters now.

“It has revitalized our community,” she says. “It’s livelier. I think there’s some hope for the future. I think the mothering instinct has come out and people kind of look over them and for them. I think they just brought a whole new dimension of youth and life to the tired old ladies — including myself,” she adds with a little laugh.

©2001 Cheryl L. Reed

Cheryl L. Reed is a freelance writer based in Minneapolis. She is traveling the country documenting the lives of modern Catholic nuns with the support of an Alicia Patterson Foundation grant.