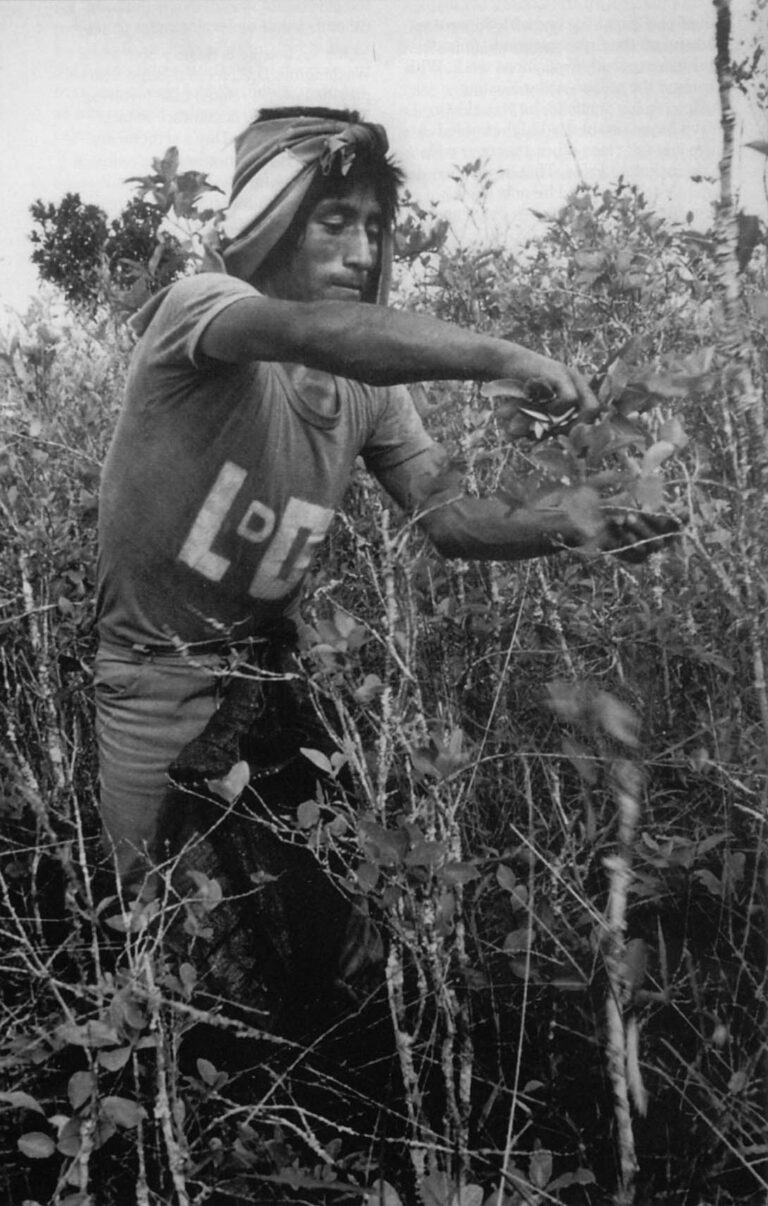

TINGO MARIA, Peru. – On her farm in a hollow in Peru’s high jungle, one woman’s pride are her tropical fruit trees. But she acknowledges that fruit doesn’t bring in money in. Nor does the coffee and cacao she and her husband grow. These days, their only cash comes from the hardy green coca bushes whose leaves, when beaten and soaked in chemicals, yield cocaine.

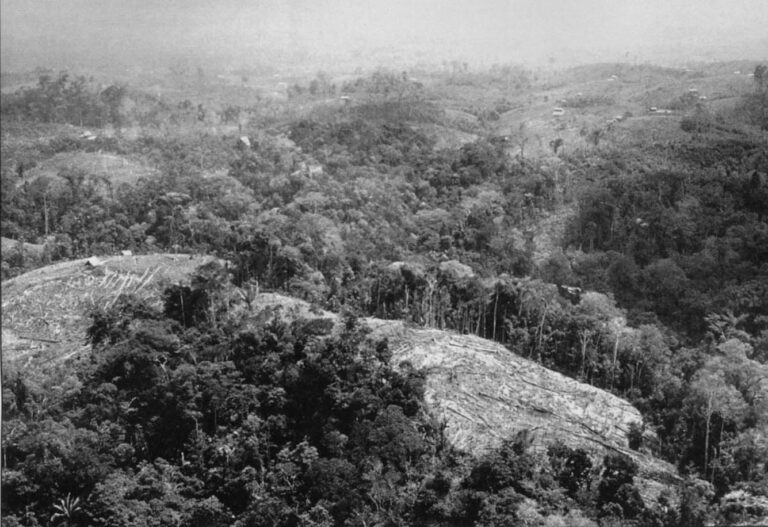

Her farm near the town of Tingo Maria is nestled in the Upper Huallaga Valley, an area where the Andes mountains plunge down to the Amazon basin. Here, climate and geography have created a unique zone of upland tropical forests which Peruvians call “the eyebrow of the jungle.” Once a paradise of rolling, forested hills, today the Upper Huallaga, covering an area just smaller than New Jersey, is best known for its most infamous crop — coca.

Coca has grown here for millennia, and Andean peoples have chewed its leaves as a mild stimulant since before the Incas. Farmers licensed with a government agency still grow coca for traditional use. But coca took on new meaning after a German chemist isolated the cocaine alkaloid in 1860. A hundred years later, the U.S. cocaine boom and the ensuing drug war made Tingo Maria synonymous with drug trafficking and U.S.-backed efforts to eradicate coca from the Andes. The campaign won a Pyrrhic victory, as coca declined locally but spread across the Peruvian Amazon. Most ironic of all, coca is now returning in force to places around Tingo Maria where, fifteen years ago, the drug war began.

On a misty March morning, the fruit farmer and her husband joined their neighbors to elect delegates to a general assembly of their farmers’ cooperative in Tingo Maria. Her husband, a rail-thin man with bushy gray eyebrows, was acclaimed as a candidate.

But turnout was poor, and the voters seemed to have a hard time taking the election seriously. “The cooperative is no longer a real option for the farmers,” co-op president Juan Francisco Enrique said sadly.

The Naranjillo coffee and cacao cooperative, which has been supported by the United Nations Drug Control Programme (UNDCP) for ten years, has fallen on hard times. Coffee prices were devastated in 1989 when, thanks to a big push from the United States, the International Coffee Agreement collapsed. Cocoa butter prices also fell in the late 1980s, and the co-op’s cacao production has fallen nearly 70% since then. The cooperative, whose membership peaked at 6,000 in the early 1980s, now has fewer than 1,000 members. Most of them, like this couple, have returned to growing coca, after having their fields forcibly eradicated in the early 1980s.

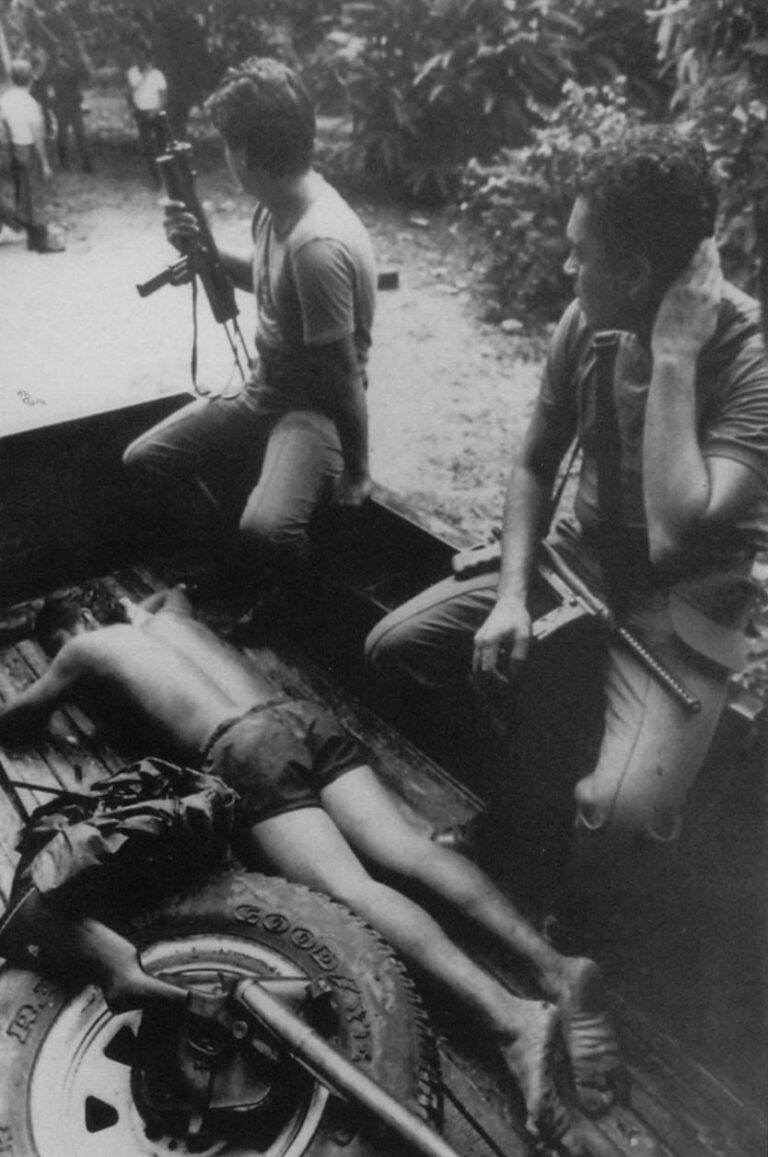

Surprisingly, the husband wishes, vehemently and bitterly, that the government would just get rid of “el narcotrfico” once and for all. “We would suffer, but in the long run we would be better off,” he said. Coca farmers live in fear, perched uneasily between the drug traffickers and the often brutal and corrupt police. But farmers who want to get out of coca face an economic and environmental labyrinth. Local labor costs more than legitimate crops can bear, as farm workers find higher wages harvesting coca or stomping the leaves in the plastic-lined pits where semi-refined cocaine is made.

Moreover, coca fields, having destroyed valuable virgin forests, tend to be useless for other crops. “No other crop provokes a similar degree of erosion,” wrote Peruvian environmentalist Marc Dourojeanni in 1990. Because coca is planted on steep slopes in area of high rainfall, is frequently weeded, and is stripped of its leaves 4-6 times a year, the soil around it is quickly washed away and leached of its nutrients. One researcher dubbed coca “the Attila the Hun of tropical agriculture.”

Whatever problems coca brings, however, the couple has no plans to give it up. There are no schools beyond sixth grade in the Tulumayo Valley, so their children had to be sent to live and study in Tingo Maria. “We wouldn’t need coca if it were just us,” the woman explained. “But when you have to send your kids away to school, where do you get the money?”

Not from coffee or cacao, despite the co-op’s efforts. Not from corn or rice, which can’t compete with cheap imports. Indeed, according to Ibn de Rementera, a development expert who has worked in the Upper Huallaga for several years, “World agricultural prices are key to the problem of coca. As long as agriculture is subsidized –until people pay what agriculture really costs– we’re doomed to fail.” He added that coca offers one more thing no other crop does–security. “The price of coca never falls below cost,” he said.

And then there’s the problem of infrastructure –the road, or lack of one. To sell his legal produce, the couple must carry sacks of coffee or cacao weighing as much 140 pounds out to the road. They will not say how they transport their coca, but most farmers around here process it into a crude gray paste, and then sell it to middlemen who send it to cocaine laboratories, in Peru or elsewhere.

“Let’s not kid ourselves,” said one of their neighbors. “We grow coca because they come to our doors to pick it up.”

Peru is the world’s largest producer of coca leaf, and the bushes grown in the Upper Huallaga Valley yield a high cocaine alkaloid content. So in the 1970s, as the cocaine boom started in the U.S., Colombian drug traffickers made Tingo Maria their coca supply center, launching “el boom de la coca.” Close on its heels, in 1979, came “Operation Green Sea I,” the first U.S.-backed effort to forcibly eradicate the coca crop. It was to be the curtainraiser for America’s long and inconclusive drug war in the Andes.

The battlefront centered on Tingo Maria. According to Peruvian government figures, in 1978 there were about 8,500 hectares of coca concentrated around Tingo Maria. By 1983, the town headquartered two new Peruvian anti-drug forces — a paramilitary police which evolved into the national anti-drug police, Dinandro, and the coca eradication force CORAH. Both were funded by the State Department –CORAH in its entirety– and the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) worked closely with the police on narcotics interdiction.

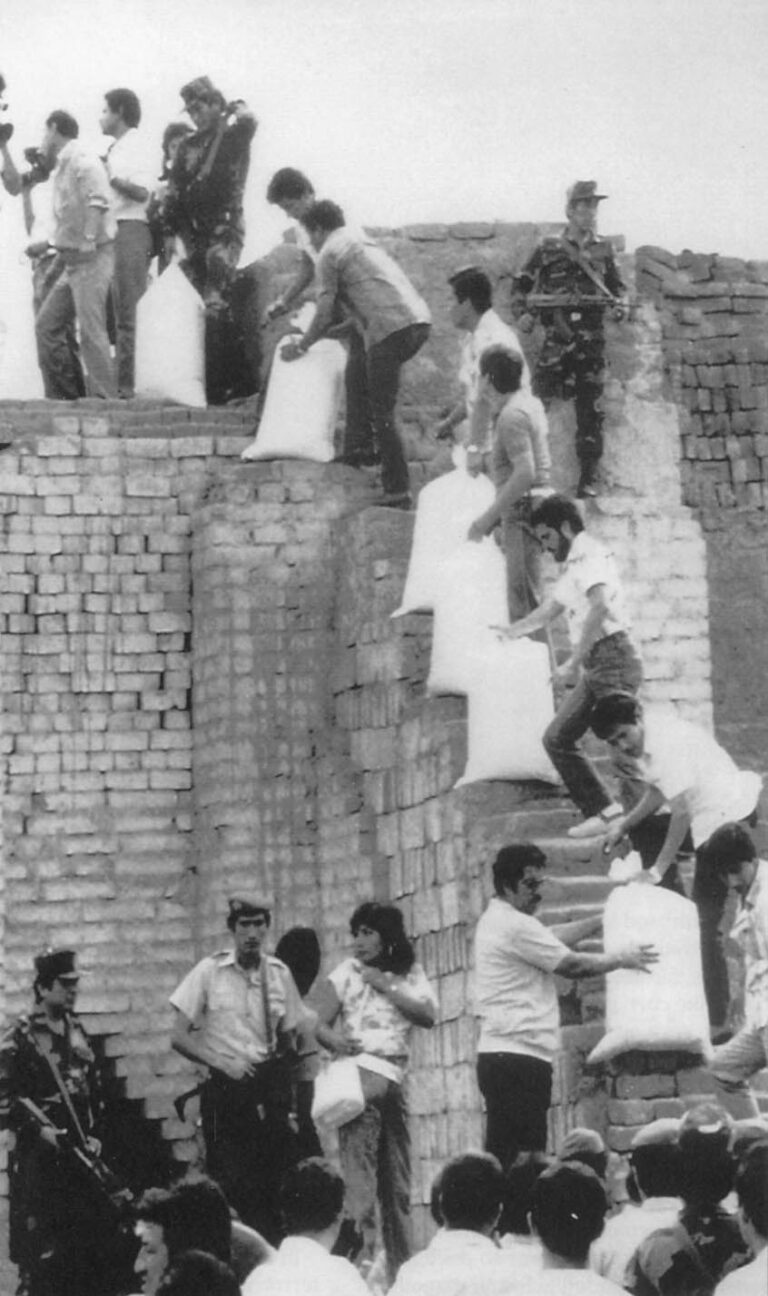

Between 1983 and 1986, CORAH’s workers tore up 8,664 hectares of coca bushes around Tingo Maria, as the farmers desperately searched for an alternative way to make a living. But while the State Department spent over $208 million on law enforcement between 1981 and 1994, the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) provided only $29.85 million on developing alternatives to the drug trade. Over the same period, the United Nations spent just over $22 million. Meanwhile, coca was bringing nearly a billion dollars a year into Peru.

Most farmers stuck with coca. “The repression centered on Tingo Maria, so people went to Tocache, Uchiza,” explained Felipe Paucar, a former coca grower who is now a radio talk show host in Tingo Maria. “Coca began to spread,” he said, opening his arms in the shape of an atomic cloud, “just like a mushroom.” By 1986, though coca was in decline around Tingo Maria, Peruvian government figures showed over 50,000 hectares of coca in other parts of the Upper Huallaga Valley.

About 80 miles north of Tingo Maria, around Tocache and Uchiza, farmers burned down thousands of acres of forest for new coca fields. In hot pursuit, in 1987 CORAH moved its operation and its 400 workers from Tingo Maria to a base called Santa Lucia, near Uchiza.

The U.S. government, under a revamped Andean counternarcotics drive called Operation Snowcap, turned Santa Lucia into a jungle fortress. Between 1988 and 1993, the U.S. spent over $50 million to fortify, operate, and maintain Santa Lucia. Along with money, the U.S. supplied DEA agents and helicopters worth about $13 million a year to run. The agents, dressed in camouflage fatigues, went out on jungle raids with the Peruvian police, burning down coca processing facilities and dynamiting clandestine airstrips. The choppers flew CORAH workers out to the coca fields, and in two years they eradicated 5,485 hectares around Santa Lucia.

But instead of going into decline, coca spread further, moving beyond the range of an unrefuelled helicopter flight, into the central and lower Huallaga valleys. Taking their cue from migrating coca growers, farmers there shifted from crops like corn and rice on the valley bottoms to coca on the hillsides. With economic crisis devastating Peruvian agriculture, as many as 100,000 more peasants arrived from around the country to cash into the boom.

As farmers slashed and burned their way northward, a 1989 U.S. congressional staff report noted that the smoke from the dying forests was so thick it sometimes grounded U.S. anti-narcotics aircraft. The farmers also surged east, towards the lowlands of Aguaytia and Ucayali, and south into the Apurimac and Ene valleys. As a U.S. congressman noted during one of an endless series of hearings on the Andean drug war, coca is like a balloon–squeezed in one spot, it simply bulges in another.

With the coca spread a revolutionary movement, the Maoist Shining Path, whose roots lay in the impoverished Andean highlands. By the late 1980s the Shining Path had established a reign of terror in the Upper Huallaga Valley, and coca growers began to flee their totalitarian tactics, spreading the coca zone still further. The Shining Path, by killing 10 development workers during the 1980s, also annihilated U.S. willingness to fund alternatives to coca.

In February 1989, faced with increasing terrorist activity and the murders of 34 CORAH workers in the previous three years, the U.S. suspended eradication efforts. Subsequent eradication campaigns focused on seedbeds, but after 1989 the mature bushes began dying from a mysterious fungus. By 1991 the fungus was epidemic in the Upper Huallaga.

The coca-killer is Fusarium oxysporum, a soil fungus common around the world. No one can say for sure why it suddenly turned so virulent against coca, or why it concentrated in the area around the Santa Lucia base. Most coca farmers blame the U.S.

But Enrique Arevalo, a professor at the agrarian university in Tingo Maria blames nature rebelling. Excessive pesticide use and massive coca monocropping created optimal conditions for an epidemic in the Upper Huallaga Valley, he said.

The United States government denies creating or spreading the fungus epidemic, though officials admit that the U.S. Department of Agriculture continues to study Fusarium as a biological control method.Ironically, Fusarium has done more to cut Peru’s coca production than anything the U.S. admits to doing. The State Department estimates that the number of hectares grown in the Upper Huallaga fell from 61,000 in 1992 to 28,900 in 1994. Over the same period, however, 22,000 hectares of new coca fields were planted in the lower Huallaga, Aguaytia, Pachitea, and Apurimac Valleys. These figures are from the U.S. government, but the Peruvian government and the United Nations believe the real amounts are considerably higher.

By 1993, budget cuts and the fact that much of the coca industry had moved away forced the U.S. to pull out of Santa Lucia. Today U.S. operations are based out the lowland jungle city of Pucallpa. The helicopters and DEA agents must travel far afield to the six regions the U.S. lists as growing coca.

With coca fields now scattered all over Peru, Juan Francisco Enriquez isn’t really surprised to see coca returning to Tingo Maria, where it was eradicated over ten years ago. “People still need eat,” he said.

©1995 Corinne Schmidt

Corinne Schmidt is a freelance writer in Peru examining the environmental consequences of the cocaine trade.