Seoul–

This is the Oriental Year of the Boar, and throughout the Far East the English-speaking punsters are having an absolute circus with that one. But here in Korea – no matter what the zodiacal charts decree – it always seems nowadays to be the Year of the Tiger.

That statement might well ruffle the oracular dignity of the soothsayers who still ply their art within the gates of this 579-year-old capital. Yet, on the basis of national character alone, the analogy holds up. With a tenacity rarely equaled in today’s fiercely competitive marketplace, the Korean people have scratched and struggled their way from the chaos of war to a rising place in the international sun.

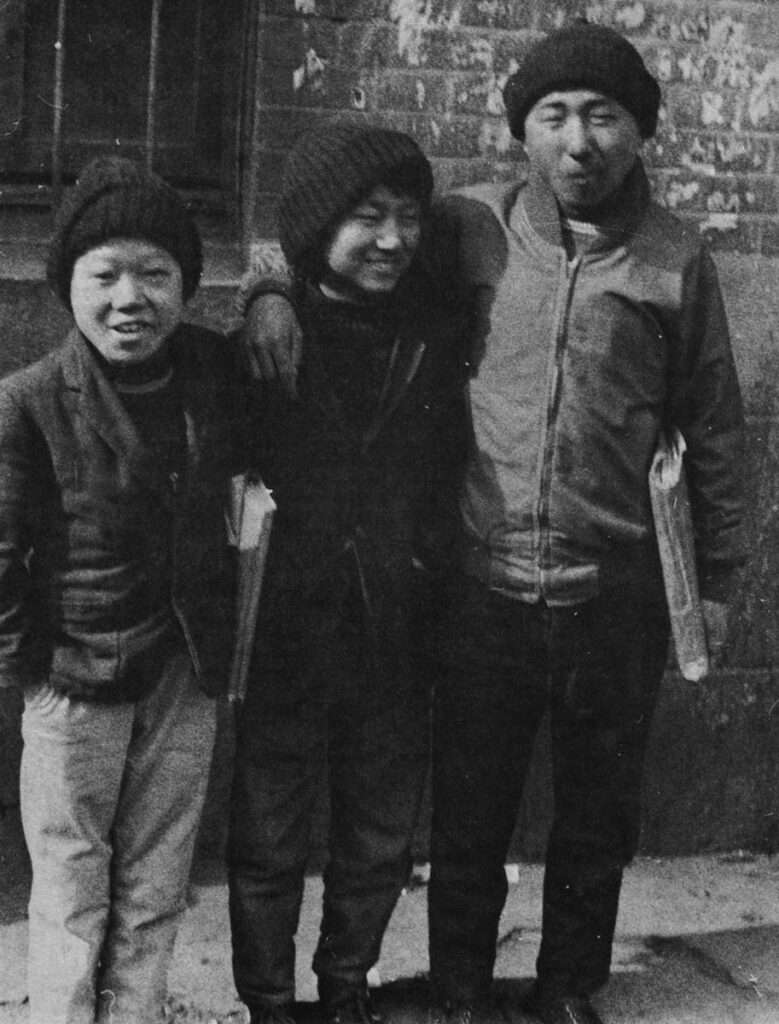

The Koreans are sometimes called “the Irish of the Orient,” and their ready humor and even readier courage has been summoned into full play during their nation’s metamorphosis from battleground to burgeoning industrial prodigy. The people laughed a lot – especially at themselves – but the transformation was not easy.

“They have pulled themselves up by their bootstraps since the war ended in 1953,” an American correspondent told me over a bottle of OB Korean beer at Seoul’s new Chosun Hotel. “And for the most part those straps were connected to combat boots. They were covered with the red dust of Korea’s mountains and in some cases with the blood of the men who were wearing them.”

Admittedly, that view smacks of the romantic. But the facts, even without embellishment prompted by the heady domestic lager, are sufficiently eloquent. Few countries, East or West, can match the Republic’s post-1960 economic revitalization.

The statistics provide documentation:

Per capita annual income, at the empty-rice bowl level of $94 a decade ago, now exceeds $200. By 1976 it is expected to top $370.

Exports have been rising at around 40 per cent yearly. Five years hence, Korea – whose exports totaled a mere $32 million in 1960 – hopes to ship about 43.6 billion worth of products abroad.

European markets are being developed rapidly, an area, which traditionally has been standoffish to Korean goods. Total exports to Western Europe last year nearly doubled the sales tallied in 1969.

In the past decades Korea has multiplied her export figures by a fantastic 3,400 per cent.

The real index of Korea’s resurgence, however, comes from a comparison of the economic phenomenon here with the postwar “miracle boom” in Japan. Korea, although beginning from a much more modest bases has actually outstripped her neighbor and former overlord in the rate of climb of Gross National Product.

Today Japan, after the United States, is Korea’s biggest market and major source of commercial credits as well. Up until 1962, not one yen of Japanese investment was present in Korea. By last year, Nipponese Investments In a wide spectrum of Korean Industries surpassed the half-billion mark.

But economic bonds sometimes fail to heal old wounds; and one senses in Korea strong tracings of anti-Japanese sentiment, especially among those over forty. The citizens who are middle-aged and beyond often retain bitter memories of the Japanese occupation which began In 1910 and lasted until the end of the second world war.

“I simply cannot bring myself to trust the Japanese, no matter how much capital they dangle at us, ” a successful Korean businessman said in his paneled offices in the KAL Building in downtown Seoul. “They are tricky, cunning and cruel. They also have conveniently short memories. Japan forgets that it was the Korean War and the million America spent in Japan staging that war that started her whole boom. Japan made the profits and we inherited the misery.”

Korean television dramas and movies often play on a theme keyed to Japanese atrocities and wartime misbehavior. But, grudgingly, traditional enmities seem to be cooling if not completely dying. This is indeed a hopeful trend, underscoring as it does the similarly directed, if not commons destinies of the two nations.

That destiny is forged geographically as well as economically and socially. At one point a mere stretch of thirty-five miles separates The Land of the Morning Calm” from Japan across the Korea Strait. Too, there are some 600,000 Koreans living in Japan and typically as Asian people they have clung to the strong family linkage with their homeland.

Japanese technological know-how, in this era of transistorized frenzy, might well be Korea’s most valuable import. Some observers feel, for example, that Japan’s maritime acumen will be the spur needed to get Korea’s budding shipbuilding Industry under full steam.

Further, the Republic’s low wages and highly-qualified working force make Korea the natural heir to the labor-geared enterprises, such as textiles, which flourished in Japan in the earlier phases of her development. Japan knows how to make that kind of peculiarly Asiatic enterprise hum; and Korea Is eager to learn.

All of this is not to say that Korea is offering herself as a kind of economic satellite of Japan. Far from It. Fiercely proud and competitive, the Koreans are making the Japanese zaibatsu, or corporate combines-, sit up and take notice, ROK textiles and electronic products are beginning to carve sharp inroads In some markets once held In a judo-grip by Japan.

Even when it comes to Oriental exotica, Korea is not to be outdone. Her export roster includes such items as grass wallpaper, mushrooms (a $10-million-a-year goal has been set for the fungus growers), agar agar, human-hair wigs and false eyelashes. And last year something like half a million chipmunks, at 600 hwan (42) apiece, were shipped to Japan. Despite the suggestion by some wags that the critters occasionally end up in the sukiyaki pot, the chipmunks are much favored by the Japanese as household pets.

Only a dishonest, or unaware, commentator would say that all is bliss between Korea and Japan. Tokyo businessmen on trips to Seoul are careful to avoid spots, such as workingmen’s bars, where their presence might start a hassle. And Japan is certainly no paradise for the Koreans who live there. To quote one of them directly, they are “nothing but second or third-class citizens.” Good jobs are hard to come by, even if the Korean is qualified. For many it there remains little choice but to join the “Japanese Mafia,” a loose federation of gangsters and strong-arm types whose bosses are often fellow Koreans.

There is reason, however, for optimism – thanks in large measure to the efforts of Korea’s dedicated and often maligned president, Park Chung-hee.

Odds are that Park will go down in history as the leader who put Korea on the map economically and militarily. But the fact remains that his first-hand knowledge of Japan and the Japanese people has been an important adjunct to Korea’s upsurge since the last World War. And that knowledge underlies in large part the continuing normalization of relations between Tokyo and Seoul.

While the rest of Korea’s future leaders were either actively resisting Japanese domination at home or from exile abroad, Park was wearing the uniform of the conqueror. Prior to World War II, he attended Imperial military academies In Manchuria and Japan. He later fought with the Japanese in China as a first lieutenant. At war’s end he returned to his homeland.

Then began what has come to be known as Park’s “mystery period.” He joined the South Korean Army but was dishonorably discharged and sentenced to death for allegedly collaborating with Communists in the Instigation of a revolt by an army regiment. Park’s political opponents, who have made much out of the affair over the years, claim he won a reprieve by informing on his fellow conspirators. His own version, when challenged publicly, was that all he had done was give refuge to some Red suspects who were friends of his brother.

Whatever the facts, Captain Park reappeared in the army shortly after the outbreak of the Korean War. He came out of that conflict a brigadier general and was promoted in 1958 to major general. In May of 1961 he was a frontal figure in the coup that overthrew the regime of Dr. Syngman Rhee. Two years later he was voted in as president – after repeatedly declaring that he would never run for that office – and is expected to win handily in this summer’s elections as he bids for an unprecedented third consecutive four-year term.

To Western eyes, Park is indeed something of a mystery leader. A British journalist – after drawing a rather unfavorable profile of him as a small, dour chap who rarely smiles and flits about the country making wooden speeches once described Park as “an enigma behind a pair of dark glasses.”

True, Park has little Sukarnoesque charisma or swagger. But to some that is a point in his favor. Charisma, all too often, has a way of turning into megalomania. Park is an austere man, a dedicated man, a tough man. He drives himself hard and expects his subordinates to keep pace.

“He who quits In the middle of the road,” Park Is fond of proverbizing, “will never be the victor.”

“And the road the President Is talking about,” says a young economics professor at Seoul’s Yonsei University, “is the road of Korea’s future.”

As Park sees it, that road lies along a two-fold path: economic development and the building up of his country’s military strength.

His concern with the former has resulted in a triumvirate of five-year plans, which have fostered land reclamation, the building of a modern highway network and a shift to heavy and chemical-oriented industries. Iron and steel, oil refining and petrochemicals also rate high on Park’s list of priorities.

The president, through the burning of a lot of midnight oil in the Blue House, his official residence, has become an adept economist in his own right. The walls of his office reportedly are plastered with graphs and price index charts. And the exporter who fails to meet his promised targets can figure on hearing from Park – personally.

According to one ROK Army subaltern – who asked not to be identified – a dressing-down from Park is an experience to diligently be avoided. Korean tempers have often been likened to the fiery kim-chi, or fermented spiced cabbages that Is one of their dietary mainstays. The officer would not go that far in evaluating Park’s flap ability. All he would concede was that “the President is a quiet man. But still water runs deep – and sometimes with a violent current.”

Militarily, there can be no doubt that Park’s patience. If not his temperament has been sorely tried of late. The chief Irritant Is the pullout, already under way, of a third of the 60,000 U.S. troops In Korea. Park has 600,000 soldiers – well equipped and most of them trained in taekwondo the native martial art that combines the more lethal elements of judo and karate – on active duty, ready to defend the 155-mile demarcation line that bisects North and South Korea. The ROK Navy boasts 20,000 men and a flotilla of fast, maneuverable interceptor craft. The Air Force, armed with American jet fighter-bombers, Is 15,000 strong.

Communist-watchers seem to agree that North Korea cannot match such muscle. The consensus also is that the Reds, with both Russia and China opposed to another 1950-type confrontation, will not be so foolhardy as to start a second Korean War.

But the statement one hears often In Seoul today is, “Uncle Sam has pulled the rug out from under us. Why?”

The hasty answer Is, In a word, economics. Economics as opposed to any snap judgment by Washington concerning the genuineness of the threat that the North Koreans may once again come swarming out of the ridges above the 38thParallel. The U.S. obviously is not turning South Korea to the wolves, but rather is trying to pare its overseas budget while stressing a policy of Asian self-help.

So the argument goes. But there is no escaping the fact that U.S. troops withdrawals will tug heavily at Korean purse strings. Invisible earnings from American forces come to about $100 million a year. That is a considerable sum in a country whose foreign exchange earnings are around $1.5 billion.

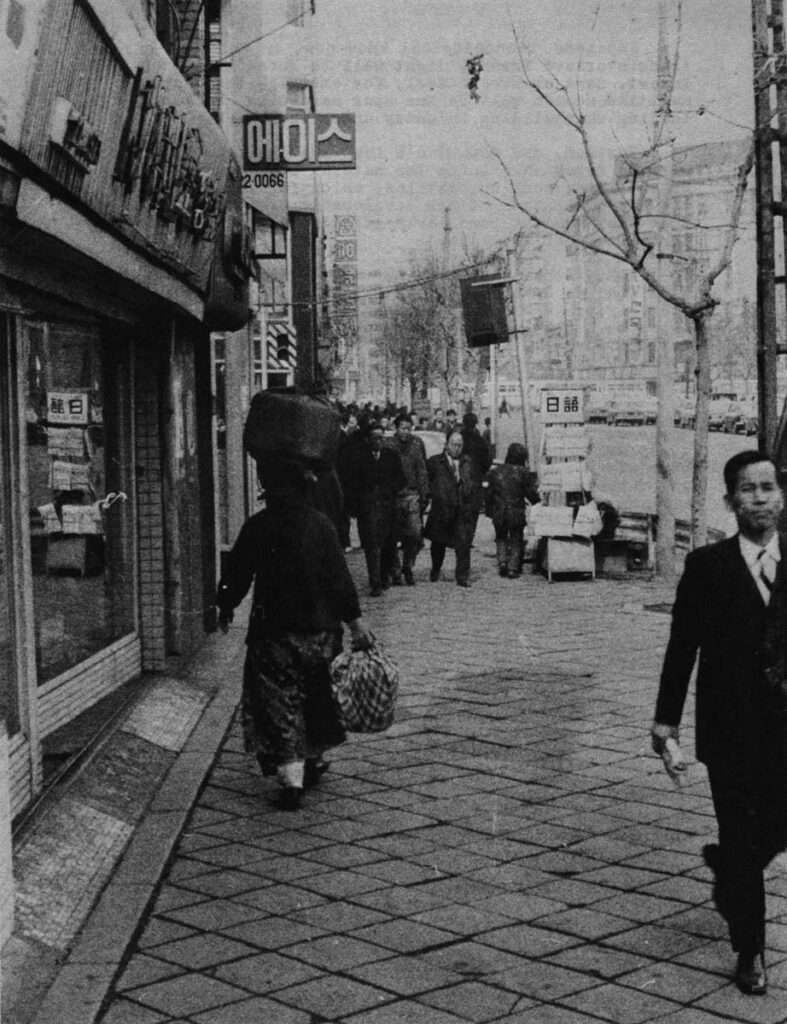

Despite the U.S. pullbacks, the specter if not the actual threat of war hangs heavy over the ancient city of Seoul. It is a city that has known conflict for five centuries. Mongols, Manchus, Japanese warlords and Chinese bandits have stormed its portals. Today, one sometimes gets the feeling that Kublai Khan himself were once more at the walls of the Kyung-Bok Palace.

Barbed wire entanglements are everywhere, and machine guns bristle behind them. Well-starched olive drab fatigues, set off by Ridgeway visored caps and loaded sidearms, are the uniform of the day. Seemingly the soldiers outnumber the civilians.

There is a midnight curfew, which extends until four in the morning. A Korean slow in putting away the “11:30 round” in his favorite cabaret faces the prospect of spending the night sleeping In a booth or atop a barroom table. If he is caught on the street after midnight he runs the very real risk of being shot as a Red infiltrator. An American tourist might get away with sightseeing past 12 o’clock, but few take the chance. Trigger fingers are itchy In Seoul these days.

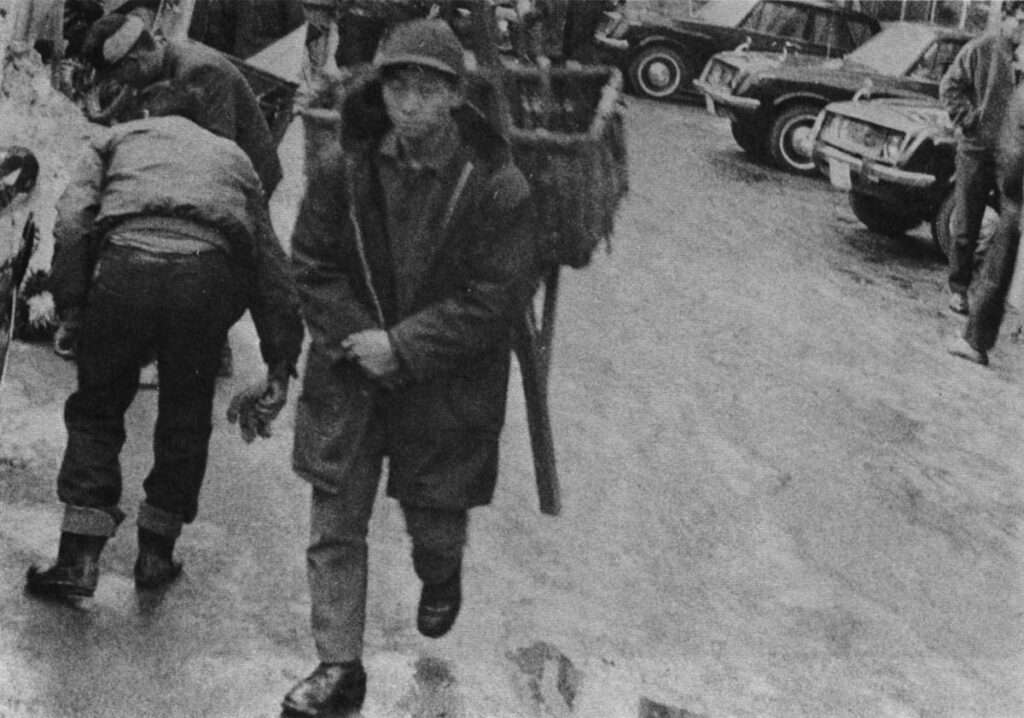

All of this takes a definite psychological toll on the populace, touching everyone from the patriarch in his stovepipe hat to the lowliest porter lugging his stupendous loads on an “A-frame” backboard.

To the foreign traveler, though, Korea is a land of many enticements – and not a few frustrations. The zealous frisking of passengers by hijack-conscious guards at Kimpo Airport, outside, Seoul, is a nuisance. They go at it with a zeal that would make Mike Hammer yelp. And the payment of a 300-hwan (99-cent) “airport tax upon departure seems a little ridiculous. But whether one prefers driving along the new Seoul-Pusan superhighway (266 miles – and no speed limit), chancing the roulette wheel at the Walker Hill casino (where the chorus line, called the Honeybees, makes the Rockettes seem somehow undernourished) or sampling bulgogi barbecue, Korea, as the brochures promise, has something for every taste.

Many a GI stationed here Is quick to agree. A sergeant in the Men’s Bar of the Bando Hotel summed it up, in a very quiet voice;

“The girls in Korea are the prettiest, the friendliest, and the loyalist in the world,” he said. “The duty over here is so choice that it’s the best-kept secret in the United States Army. I don’t even know why I’m telling you.”

American soldiers like the appreciative sergeant figure to be on the scene in war-divided Korea for a long time to come. But the pendulum is lobbing toward self-help – and self-reliance.

The props, which the U.S. has provided over the past quarter of a century, are gradually being nudged aside.

President Park’s road to national destiny is not without its chuckholes. In Korea, where democracy is much discussed as a theory but rarely put into actual practice, politics can sometimes turn into a rock fight. Opponents of Park, for example, have charged him regularly with election rigging. They also feel that he is engaged in the same sort of tampering with the Constitution (particularly after the referendum allowing him to run for a third straight term) that in part was responsible for the collapse of the despotic regime of Dr. Rhee.

Right now, Park’s government Is facing a crisis involving the murder of a popular, and wealthy kiesang girl, the Korean equivalent of a Japanese geisha. Former premier Chung Il-kwon has been dismissed in a cabinet reshuffle as rumors persist that he fathered the murdered courtesan’s three-year old son, Song-il. Park, an austere – and careful – politician, has thus far stayed above public reproach.

Despite such painful sidetrackings, the future of the Republic of Korea and its 33 million Industrious, strong-willed people can only be colored promising.

There is a new dawn sweeping the Land of the Morning Calm. And, as Kipling wrote of another brilliant advent, it has indeed come up like thunder.

Received in New York on March 15, 1971.

©1971 Darrell Houston

Darrell Houston is an Alicia Patterson Fund award winner on leave from the Seattle Post-Intelligencer. This article may be published with credit to Darrell Houston, the Post-Intelligencer, and the Alicia Patterson Fund.