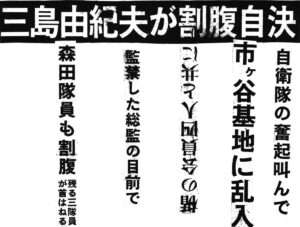

In the wake of the ritual suicide of Yukio Mishima, Japan’s leading novelist, a profitable – and at times macabre – cultural phenomenon has evolved. The Japanese, who are much given to instant labels, call it the “Mishima Boom.”

It is an apt designation. Mishima posters flutter overhead on trains and subways. Magazine articles cover his life, literally, from the cradle to the blade. His books are selling like rice cakes, something that rarely happened during the author’s lifetime. A hara kiri film, starring Mishima, has enjoyed a lucrative revival. Nippon Columbia has issued a long-play record of him reading his own works. Thankfully, nothing quite as gauche as Mishima sweatshirts has appeared. But at least three Japanese youths, inspired no doubt by the novelist’s example, have tried to disembowel themselves in public. All three managed to thoroughly botch the job.

As a further offshoot of this peculiarly Japanese obsession with Mishima memorabilia, a new intellectual parlor game bas been born. Its label might well be “Why Did Mishima Do It?” The game is a fascinating, if futile, pastime. There are neither rules nor restrictions on eligibility. You can be a fellow playwright who knew Mishima well. Or the proprietor of a gay “love motel” who claims the controversial writer was one of his steadiest customers. You can be a foreign correspondent who drank brandy with him often and remembers him as “a helluva good guy and a fine boozer.” Or the American matron who loathed him because he once posed for the cover of one of his novels in nothing but a headband and a jockstrap. You can be the young Japanese soldier who admired him “because he was so fond of Hitler and the Marquis de Sade.” Or you can be that soldier’s commanding general who dismissed Mishima and his farewell scene as the bizarre exhibitionism of a madman.

Everybody is getting in the act.

But it doesn’t matter who you are or how eruditely or glibly you play the game. Always, one constant emerges: No two persons ever come up with the same answer.

Hideo Nakai, a writer who was a close personal friend and confidant of Mishima, has a unique theory about the 45year-old Nobel Prize candidate’s suicide.

“I cannot help but feel that there may have been two Mishimas,” he says. “I know it sound mystical, but the other Mishima may still be alive, may appear anytime rubbing his eyes, which have become red after hours of writing, and say, ‘So he (the original Mishima) did that finally?’ And then he’ll start hurling invective at the original Mishima to set the public mind at ease. Then the other Mishima will disappear and kill himself in a lonely, less public, way.”

Taruho Inagaki, also a writer, feels that Mishima committed seppuku (hara-kiri) because of an inability to handle his-own deep-rooted narcissism.

“Narcissism is the mainspring of art,” Inagaki says, “but in Mishima’s case it was not introverted but rather was extroverted without restrictions. Mishima’s writing lacked nostalgia, so that the more he wrote the more artificial he became.”

Tokyo University’s Yuzo Horigome sees a definite parallel between Mishima’s suicide and the death of Thomas Beckett.

“Beckett’s death was described by a knight in Eliot’s ‘Murder in the Cathedral’ as suicide while of unsound mind,” Professor Horigome points out. “Beckett built his own religious world of fiction and met his death while fighting the deception of the secular world. In the same way, Mishima was so faithful to his world of fiction that he could not stand the real world of deception.”

Saneatsu Mushakoji, another intellectual, is eighty-five. But he still considers himself to be “too young to understand the true meaning of death.”

“Seppuku is a barbaric act,” Mushakoji says. Then he adds, as do so many of his confreres:

“But still I cannot help but admire the fact that Mishima did it in such a beautiful and aesthetic way.”

One intellectual, however, feels that it was Mishima’s artistic and personal aesthetic that led to his death. Masaki Kobayashi, who directed the film “Seppuku” in which Mishima played the ill-starred lead, says:

“I can understand Mishima’s suicide as a writer. But as a revolutionary or politician he was utterly childish. My opinion is that Mishima was under the spell of his aesthetic consciousness when he killed himself in the Ichigaya garrison of the Ground Self-Defense Forces.”

This seeming preoccupation with the aesthetic aspects of Mishima’s hara-kiri of last November 25 is by no means limited to the intellectuals alone. Japan’s revolutionary students, sensing that at long last a martyr to their cause has emerged, are equally sensitive to the “beauty” and “purity” of Mishima’s farewell drama. A letter from a young Tokyo student named Yoshinori Arai, written to the editor of an English-language newspaper, is fairly typical:

“Mishima…decided firmly to die beautifully and fantastically for his own happiness. His hara-kiri suicide may be a bad thing from a social point of view, but I consider that each individual is living for his own sake, seeking more happiness. He died happy.

“We should not try to think of or trace the reason for his death by logic, because logic is an imported study, not the traditional Japanese way. The Japanese traditional way of thinking is beyond logic, as is Zen.

“Mishima Yukio is my favorite person and author. It is now about nine years since I encountered his work for the first time. I have no doubt that I lived my youthful life with him. I can touch his death by feeling. The death of Mishima will be one of the treasured memories of my youth, which I am now leaving behind…”

A recent poll conducted by the mass-circulation Asahi Shimbun underscored the traumatic effect Mishima’s deed has had on Japan’s students. Leaving aside political judgment, nearly thirty per cent of those polled said they were in full sympathy with Mishima’s feelings. Another thirty per cent said the incident left them in a state of profound shock. Out of the remaining forty per cent some thirty-two per cent felt that Mishima’s hara-kiri was “a stupid thing to do.”

“The incident had a bad psychological effect on us students who are right now in our character formation period,” a second-year man at Tokyo’s Waseda University said. “I reject his actions because, although on the surface they seemed to be political, they were done for purely personal reasons.”

Aesthetics or politics aside, it has been said that if you scratch the skin of the average Japanese you will find the tough hide of a Samurai warrior underneath.

Japanese police, ever watchful of student activities and trends, are aware of the truth inherent in that cliché. Officials of the National Police Agency (NPA), citing the Mishima affair as one of the prime impellents, predict that 1971 will see an upsurge in student violence.

A report on the Mishima case published last December by the NPA provides documentation. The report noted that there are now more than 450 rightist organizations in the country – some of them openly patterned after Mishima’s private army, the Tate-no-Kai or Shield Society – with a total membership of 115,000. Also reported was a brisk increase in the number of leftist groups and a swelling of the ranks of those already in existence.

Police expect the student violence to crest with the reversion to Japan of Okinawa in 1972. Right now they can only sharpen training, beef up their ranks and keep their lines of information open.

“We have already reinforced the guard at the American Embassy in Tokyo,” says Kenji Tejima, deputy chief of the NPA’s investigative section. “Also, we will give the utmost protection to visiting foreign political figures, and increase the Embassy compound guard as necessary.”

Tejima admits that the specter of Mishima looms large behind the legions of both the left and the right, particularly the latter.

“Following Mishima’s lead,” he says, “they are calling for a revision of the Constitution and some are advocating action against political and financial leaders.”

Tejima continues: “It is true that many on both the right and the left admire Mishima and what he did. For instance, speculation about a ‘revival of the Bushido Code’ is very widespread these days.”

Thus Bushido, the Way of the Warrior, remains alive to many as a virtue – even though it long ago died as a system. But many in today’s Japan seem to be too dazzled by superficialities like Mishima headbands and Mishima wall-posters. They are forgetting that, for a true Samurai, to hasten death – and above all to court it – was considered the basest cowardice.

The highest valor in times of stress was to dare to live.

– the end –

Received in New York January 25, 1971

©1971 Darrell Houston

Darrell Houston is an Alicia Patterson Fund award winner on leave from the Seattle Post-Intelligencer. This article may be published with credit to Darrell Houston, the Post-Intelligencer, and the Alicia Patterson Fund.