– Hokusai

"Now the Self is the state of being of all contingent beings. In so far as man pours libations and offers sacrifices, he is in the sphere of the gods; in so far as he recites the Veda he is in the sphere of the seers; in so far as he offers cake and water to the ancestors, in so far as he gives food and lodging to men, he is of the sphere of men. In so far as he finds grass and water for domestic animals, he is in the sphere of domestic animals, in so far as wild beasts and birds, even down to ants, find something to live on in his house, he is of their sphere."

– The Brihadaranyaka Upanishad.

"ECOLOGY: Eco (oikos) meaning house (cf. "ecumenical"); housekeeping on Earth."

– Gary Snyder, "Earth House Hold"

"…Everything we have thought about man's welfare needs to be rethought…Let poetry and Bushmen lead the way in a great leap forward…."

– Ibid.

"Why don't they just hire planes and spray Chanel No. 5 over the country?"

– Jackie's response when told by President Kennedy of the growing danger to America's environment

Tokyo –

In Japan, pollution – whether you pronounce it with two l’s or two r’s – is a very dirty word. Because, for man and beast alike, there simply is no escape from it. It is in the air you breathe. It is in the rice and fish you eat. It fouls the beaches where you try to swim. It fosters some of the most baffling diseases in medical history. It pounds at people’s eardrums around the clock, accelerating the flow of adrenalin and infringing on their territoriality. Some, as a result, end up in mental institutions. Family cats begin to do strange midnight dances, then hurl themselves into the sea. Animals in municipal zoos have nervous breakdowns.

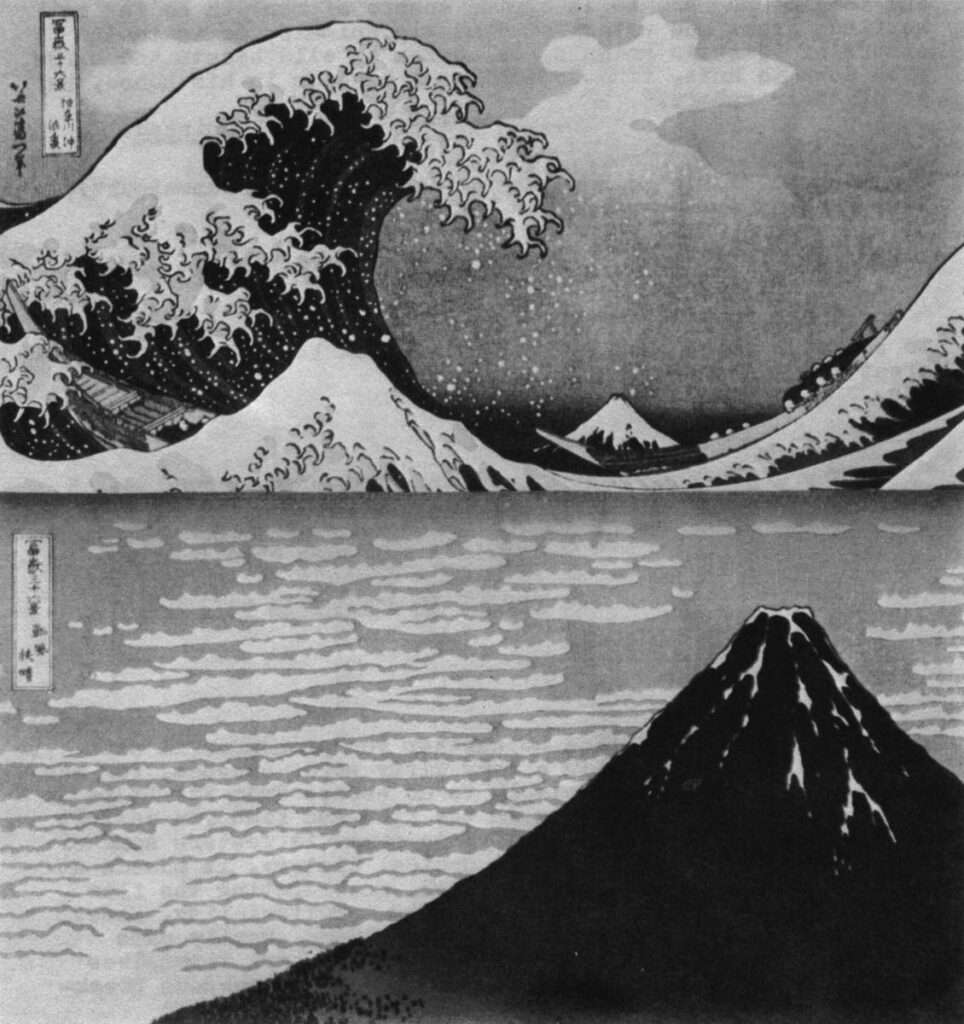

As if that weren’t enough, the scourge of kogai (pollution) has now desecrated the very symbol of Japan itself, Mt. Fuji. Not only are the slopes of that sacred volcano wantonly littered by the multitude of pilgrims who trudge to the 12,388-foot summit each summer. But the mountain has practically become invisible. Rare indeed is the day when Fuji-san, some sixty miles to the southwest and once a Tokyo guide mark, can even be seen through the smog cap of the world’s largest – and grimiest – city.

Traditionally, the Japanese have been almost fatalistically resigned to such malevolencies. Traditions here of late, however, have become a great deal like the cherry blossoms: once they start to fall there is no holding them back. No longer do the Japanese dismiss their ecological travails with a shrug and a blasé “Shikata ga nai” (“It cannot be helped.”) Today, with the same energy and sense of destiny that has skyrocketed their Gross National Product to the third highest in the world, they are in the process of applying some tough legislative judo to the whole gamut of pollution and pollution-related problems.

Japan’s environmental offensive thus far has been relatively low-key, and marred to a certain extent by charges of the Sato government “selling out” to the zaibatsu, the giant industrial combines, by inserting convenient loopholes in the recently-passed anti-pollution legislation. Certainly, the environmental strides that have been taken have not received the publicity given such foreboding episodes as outbreaks of Minamata and; “Itai-Itai” disease, the despoiling of rivers by lethal tracings of cyanide, the contamination of rice crops, or the rising number of deaths thirty-seven of them in the factory city of Yokkaichi – alone directly attributable to poisoned air.

But again like the cherry blossoms, hope is blooming amid the blight of Japan’s technological jungle. If all goes according to schedule (and schedules are so strict that if you catch the 5:16 commuter at 5:18 at Tokyo Central Station, you’ve got the next train) the indications are that today’s smoke-scudded industrial wasteland will become tomorrow’s Oriental Eden.

Futurologist Herman Kahn, in Tokyo for a business seminar, predicted that by the year 2000 Japan will have achieved a $3 trillion GNP and thus oust the U.S. from the No. 1 position. The 300-pound think-tanker also forecast that by 1980 Japan will spend $100 million to control pollution and transform itself into a veritable garden spot. “The central problem of the last third of the 20th Century,” Kahn said, “will be the ‘meaning and purpose’ problem. What constitutes a meaningful life, in other words? A meaningful life also means a pollution-free environment. In Japan their highways and urban projects look terrible now because they aren’t interested in solving these problems. When they decide to spend the money, though, they’ll sit down and do sensible studies. The same is true of the pollution situation.”

Ralph Nader, America’s self-proclaimed public protector also visited Japan recently for a first-hand look at consumer and pollution problems here. Nader too took a look into the future. “Japan is beginning to be very sensitive to pollution problems because of their small area compared to the density of the population,” he said. “They can’t afford the luxury of destroying their environment to the extent that we can in America because of the large spaces we have.”

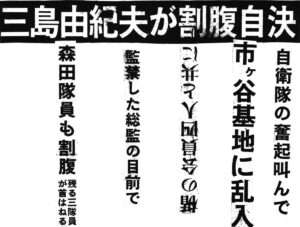

Since the visits of Kahn and Nader, Japanese government officials and legislators have to some degree made their prognostications look fairly good. During the recently concluded “Pollution Diet” (the first postwar Diet in which representatives from Okinawa sat side by side with their Mainland colleagues) fourteen environmental bills, ranging from control of sea and pesticide contamination to the curbing of traffic noise and the squelching of chemical odors, were passed. The session was of course somewhat upstaged by the hara-kiri suicide of novelist Yukio Mishima. Yet, despite howls from the opposition, that the government had capitulated shamelessly to the zaibatsu interests, the session at least made the first concerted effort to keep Japan from literally poisoning itself. Throughout, there was an awareness that the battle was one of life or death.

The most controversial item in the fourteen-measure package was the so-called “Crime of Pollution” bill. As originally drafted by the government it provided for up to seven years in jail or a fine of five million yen (approximately $16,000) for firms or individuals convicted of industrial polluting. In its initial form, the bill was Samurai-tough, with its key clause designating as liable for criminal action “those who have given rise to conditions with the possibility of causing danger to the lives of people in general or their bodies.”

The zaibatsu screamed – loudly and in unison. They were unanimous in labeling the “Crime of Pollution” bill as vicious and unrealistic, pointing out that it was without precedent in any other country. The Japan Chamber of Commerce and Industry and the Japan Committee for Economic Development (Keizai Doyukai) immediately went to top executives in the Liberal-Democratic Party of Premier Eisaku Sato and lodged angry protests. Keianren, or Federation of Economic Organizations, applied considerable pressure, too. That group, a powerful lobby force, in the Diet, maintained that the bill ran counter to the Japan Penal Code, which works, on the principle of “the benefit of the doubt.” It would not be easy, the Federation insisted, to distinguish between cause and effect when one seeks to brand an alleged polluter a criminal. “We do not want ‘instant pollution control,'” the lobbyists maintained. “It is absurd to institute penal provisions against the ‘crime’ of pollution when such a dearth of scientific evidence as to what relationship there is between cause and effect exists.”

Opposition forces – with some substantiation – claimed that the zaibatsu threatened to withhold election funds from Sato’s party if the “Crime” bill was not de-fanged. But whatever the cause in this instance, the effect of that behind-the-curtain intrigue was soon evident. Surgery was called for and performed with speed and precision, apparently along the lines sketched out by the opposition. With the amputation of three crucial words, the possibility of (causing danger to the lives of people, etc…), the penal clause of the “Crime of Pollution” measure lost most of its bite. The zaibatsu were appeased, for the time being. But the nation’s press and the ordinary Japanese, the Watanabe-on-the-street, were not.

A popular columnist in the mass-circulation Asahi Shimbun wrote: “There probably is no precedent in which a bill prepared by the government was revised so openly in front of everyone’s eyes as a result of outside pressure.”

A postal clerk, interview by a public opinion pollster for another large newspaper, gave further evidence that freedom of speech is liberally exercised in the New Japan.

“What is one to expect, after all?” he asked. “We are nothing but human guinea pigs as far as pollution is concerned.

“Recently I went to the mountains for a weekend outing with my family,” he continued, warming to his topic. “At first, I couldn’t figure out what that strange smell was. Then it came, to me. It was fresh air!”

Despite the political huffing and puffing, a rising zephyr of optimism has sprung up in the wake of the “Pollution Diet.” In one vital action, the basic environmental law has been broadened to give prefectural governors wider powers in the war against pollution. The governors now have the authority to restrict vehicular traffic if pollution levels surpass bearable standards. (Critics are quick to point out, however, that nationally no standard criterion for “bearable standards” has been established.) They also will function as pollution policemen, with the right to make spot checks on all facilities in their territory with the potential for over-polluting the air or the water system.

The significance of these now prerogatives is that, for the first time, the mandarin bureaucrats in Tokyo are at least making gestures toward giving the people and their elected representatives something besides words to hurl at the ogre of pollution. But although it is heartening that the prefectural cousins are at last to have a voice, sectional rivalries still greatly hamper the environmental pollution policies, and their effective execution. For example, the administrative control of water quality involves no less than eleven ministries and agencies. Relations between the national government and local autonomous bodies are outwardly polite but inwardly strained. In an ironic but confusing twist, some local agencies have set up tougher anti-pollution standards than those promulgated by the Tokyo government. Here, a vigorous schism of opinion occurs: one side argues that, since pollution problems are, peculiar to the regions in which they evolve, jurisdiction should be funneled from the government to local offices; the other side holds that administration of pollution restraints cannot be objectively handled locally because there will be favoritism shown to certain industrial enterprises.

While the wrangling goes on at the administrative level, the citizenry has likewise not been at a loss for words. The Home Affairs Ministry, much to its amazement, has noted that the once passive Japanese populace registered a total of 40,854 complaints against pollution to local government offices last year. And an even bigger flood of gripes is expected when the Environmental Protection Agency – which will function as a sort of ecological watchdog – opens its doors next October.

In one of the more bizarre of the rash of anti-kogai demonstrations, which, along with consumer boycotts, are, becoming almost daily occurrence in Japan was a march by Tokyo housewives. In the manner of militant students, they shouted slogans and wore headbands. Shaken government officials have yet to recover fully from the trauma of that tableau. Bands of saffron-robed Buddhist monks, intoning “Curse on thee, O polluting industrialists,” have taken to picketing outside the gates of smoke-belching factories and refineries. And one of Japan’s most honored “human national treasures,” 57-year-old Shohei Miyairi of Nagano Prefecture, has gotten into the act. Miyairi, designated an official “intangible cultural asset” by the government in 1963 for his skill as a maker of fine Japanese swords, laments: “My art, alas, is becoming nothing more than a craft. It’s all because of pollution. The, water and soil I use in my ancient hardening process – which involves the wedding of four hard and four soft plates of steel – is contaminated.”

One of the results of this public outcry was a promise by the government to study ways of cutting down the noise made by the 130-mph. Bullet super express trains as they zip along the 320-mile New Tokaido Line between Tokyo and Osaka. Residents near the tracks complained that the din was so bad they couldn’t hear their television sets and were forced to learn lip-reading in order to follow the dialogue of their favorite programs.

Also in response to the clamor, but in a somewhat less offbeat vein, the Construction Ministry has laid plans to build six pilot “play cities” around the country. Each will have “sun unobstructed by smog, luxuriant vegetation, clean air and water, and hotel and recreational facilities,” according to the Ministry. The cities – replete with such exotic diversion grounds as baseball diamonds, soccer fields, golf courses, snowmobile courts, surfing beaches, undersea pastures, man-made lakes and skiing grounds with perpetual snow – are blueprinted for completion by 1975. And this year a dozen scenic areas, including the Ogasawara island chain, which encompasses Iwo Jima of World War II lore, will be designated as either national or quasi-national parks.

In Fuji City, the building of a thermal power station by the Tokyo Electric Power Co. never got off the ground due to vehement opposition from a 5,000-member citizens council. The opposition to the plant was far from subtle; last year a band of aroused citizens rushed into the city assembly hall in a small-scale banzai charge and informed startled officials in no uncertain terms that the thermal complex was not welcome in Fuji City. In Chiba Prefecture, pressure from the citizenry has prodded the local government to not only shut the prefecture to “pollution-inclined industries” but to launch a scrupulous check of existing projects with pollution potential. At Iwaki City in northeastern Japan, citizen panels have held forthright talks with industrial leaders and forced them to spell out precisely their plans for circumventing environmental pollution.

Nationwide, big business has been quick to take the cue. The zaibatsu are quietly seeking ways to improve their public relations image through anti-pollution ad campaigns and by pushing research for equipment – such as an emission-free copper smelter being developed in British Columbia that will allow them to reap the profits of the postwar “Economic Miracle” without being publicly stigmatized – if not actually brought to task – as being of the new breed of civic criminals. An industrial manager at an executive seminar set the tone of the zaibatsu’s seeming about-face on the ecology crisis when he said: “Growth deserves the name of growth only when it can maintain a balance with society, environment and politics.” One cement firm outside Tokyo, however, carried its concern with pollution to the extreme. Under fire from citizens for the huge dust cloud its plant issued, the firm went all-out for environmental control. Management spent so much money – including its employees’ Christmas bonuses on filtering equipment that the whole outfit went bankrupt.

Labor Unions, much maligned as being “agog with apathy” toward their fellow citizens’ antipollution efforts, have also jumped on the environmental bandwagon. Whereas formerly the unions’ main facets of discontent were keyed to such topics as the high cost of living, a-shorter work week and the scrapping of the U.S.-Japan Security Treaty, now they, too, are talking about “meaningful lives!’ and the necessity of a healthful physical environment. Not all observers, though, are convinced that the unions’ sudden interest in Japan’s pollution ills is sincere. Tasuku Amisawa, a magazine commentator, has pointed out that many of the unions are organized as “tools” of specific enterprises and that their fight against ” public hazards” (a common catchall environmental phrase in Japan) is little more than political smoggery.

Bizarre though the campaign can be on occasion, the Japanese – against a media backdrop of almost incessant pollution appraisal and information – are probably the most kogai-conscious people on earth. (Unfortunately, as many a foreign visitor has commented, this doesn’t keep them from littering their parks and beaches into garbage dumps and heaping miniature Mt. Fuji of refuse on every neighborhood street corner.) One theory, admittedly far-fetched, has it that the zaibatsu are financially behind a campaign to media the anti-pollution drive to death. Still, only a very brash, or exceedingly stupid, public official would take lightly the emotional involvement of the populace.

Over the New Year’s holiday, the chairman of the National Public Safety Commission found this out rather abruptly. In Omuta City, Fukuoka Prefecture, Kyushu, to make a speech, the chairman was asked about environmental pollution – and. specifically about the rice in the region that is contaminate& by cadmium from the exhaust gases and waste waters of zinc refineries. Repeated outbreaks of Itai-Itai disease (a malady in which the victim “hurts all over.” In Japanese, itai-itai means ouch-ouch.) in Fukuoka and in Toyama Prefectures make the subject a very touchy one indeed. Purportedly a bit flush-cheeked from a few holiday toasts, the chairman replied that the rural folk should stop complaining so much. “The human body,” he said, “has functions to discharge foreign elements. I would say you people simply must have the spirit to eat contaminated rice.”

Fortunately, it was New Year’s and the holiday rather than the “let-them-eat-tainted-rice” spirit prevailed. But an embarrassed government is still trying to smooth that one over.

Even more dreaded than Itai-Itai (increasing distrust of “security levels” of cadmium density in unpolished rice by farmers and consumers has forced the Ministry of health and welfare to restudy the present standard of 1 part per million) is Minamata Disease. Minamata is a severe intoxication of the central nervous system caused by methyl mercury compounds in fish and shellfish. It was identified as a disease in May of 1956 by Dr. Hajime Hosokawa, then director of the Minamata Factory Hospital in Kyushu. On his initiative a local research committee was organized by physicians and district health officers. The following facts were established:

-

The first known case appeared at the end of 1953 and several cases subsequently were detected in the same district.

-

By 1956 the disease had reached epidemic proportions.

-

Observed symptoms were new and unknown to medical literature.

-

Somewhat similar symptoms were observed in cats in the same village before they were detected in humans. The felines often performed a wild gyrating dance and then plunged into the sea, apparently committing suicide.

-

Most of the human victims were fishermen and their families, and there was a distinct tendency for successive outbreaks in the same family.

-

The diet of all the victims – including the berserk felines – was fresh fish from Minamata Bay.

-

The disease is not infectious, the late Dr. Hosokawa found, and probably was caused by chemical intoxication from fish and shellfish.

The manifestations of Minamata are frightening. First, there is a numbness of the limbs and lips. Ataxia, or loss of muscular coordination, appears along with serious disturbance of motor functions. Speech becomes slurred. The simplest tasks – drinking a cup of tea or tying the sash of a kimono – become Herculean in scope. In extreme cases, victims lapse into a coma, twitching and shouting.

Dr. Hosokawa, surely one of the great names in modern epidemiology, turned to the dancing Minamata cats for the answer to this modern plague. Working in the company laboratory of the Shin-Nihon Chisso Hiryo Co., a fertilizer-manufacturing firm whose mercury effluents were being discharged directly into Minamata Bay, Hosokawa fed the tabbies a solution concocted from this waste. He discovered typical Minamata Disease symptoms in the cats in October of 1959. But his discovery was forcibly kept under wraps. The company ordered Dr. Hosokawa to halt his research and refused to disclose his preliminary findings. After long negotiations with Shin-Nihon, Hosokawa finally published a resume of his experiments, which conclusively linked Minamata Disease with methyl mercury discharges into the Bay, in medical journals. The public, however, remained apathetic – until 1965, when the disease erupted again. By now everybody in Japan knew about Minamata Disease, and what causes it. And it has become, an international phenomenon, with cases occurring in Sweden, the United States and, reportedly, even in Italy.

Since 46 persons have died from Minamata in Kumamoto Prefecture alone, and a further 75 there are still suffering from the affliction, the government has been closely involved in negotiations concerning compensation for victims. The usual solatium has been ¥ 2 million (about $6,500) for loss of life plus ¥ 380,000 as an annual pension and a single sum of ¥200,000 paid to survivors of the victims. Most of the public feels that these sums are ridiculously low and that the government is putting human life on a bargain-basement level. Several suits are now pending in court, and are being closely watched. The crux of these cases centers around the issue of whether the companies continued to discharge industrial waste containing methyl mercury even after they became aware of its direct causal connection with Minamata Disease. In addition to the Minamata suits other actions are pending concerning Itai-Itai (24 dead, and 97 affected in Toyama Prefecture) and Yokkaichi asthma (37 fatalities, more than 500 affected) at Yokkaichi City in Mie Prefeature,

(In one of those chilling, obscure footnotes to the chronicle of man’s tampering with the Great Cycle that is Nature, a small story at the bottom of the back page in a daily Tokyo newspaper tells of a seventeen-year-old lad in Yokkaichi, unable to breathe in the polluted air, hanging himself in his bedroom…)

At first scan it is hard to share Herman Kahn’s belief that by the end of this decade Japan will be the garden spot of the East if not the world. For one thing, no workable machinery for bearing the cost of anti-pollution measures has been set up. The zaibatsu, with their multi-billions, can afford their own preventive apparatus. But the small and medium businesses axe in trouble. They can apply for loans from the Public Nuisance Prevention Corporation, but the finances of that agency are skimpy, to put it kindly. Legal loopholes in the basic environmental control law – specifically the one that says all antipollution measures must be “harmonized with the sound progress of the economy” – give rise to fear that the current obsession with Gross National Product, often at the expense of human welfare, will not magically change overnight. Some members of Sato’s government have openly asserted that they will never “neglect the growth of the Japanese economy in order to carry out anti-pollution measures.”

The situation is taking its toll, too, on the national psyche. Dr. Masakatsu Shiozaki, chief psychiatrist at Tokyo’s Aisei Hospital, estimates that more than one-third of Japan’s working force is in the preliminary stages of neurosis. “All they need,” he says, “is one little push on the back to go round the bend.” Although the population is settling into a static trend, Japan still leads the world in population density on available livable land. The daily bombardment of traffic noises, industrial odors, vehicular tangles and rush hour scrumming has become an infuriating way of life. Dr. Edward T. Hall, the anthropologist, has said that every living thing has a physical boundary that separates it from its external environment. He calls that inner enclave territoriality. There are strong indications that the growing encroachment upon the territoriality of the Japanese is at least cursorily linked to their growing mental epidemic. The “Tokyo Resolution,” adopted at the International Symposium on Environmental Disruption in the Modern World last year, states that “to live in a comfortable environment is man’s fundamental right.” It is axiomatic to add that a meaningful life is one in which every citizen has room – and clean air – to breathe. Few in the New Japan possess those two luxuries today.

The pat remedies abound: Some hold that population redistribution and emigration is the answers. Others say the government must diversify, pay less attention to coping with actual environmental damage and introduce comprehensive and systematic measures to arrest pollution. A few would extend the joint U.S.-Japan Cooperative Program in Natural Resources, which has touched on everything from desalinization to the taming of earthquakes in the six years of its operation. None will deny that pollution education, beginning on a kindergarten level, must be implemented – if only to combat public littering and garbage strewing.

But the people, this observer feels, will win out as Kahn implies. Aesthetics, still the core of the Japanese character, will triumph over transistorized frenzy. And who knows. Someday you might even see Mt. Fuji.

Received in New York on January 13, 1971.

©1971 Darrell Houston

Darrell Houston is an Alicia Patterson Fund award winner on leave from the Seattle Post-Intelligencer. This article may be published with credit to Darrell Houston, the Post-Intelligencer, and the Alicia Patterson Fund.