Tokyo

…They came, their legions undulating like animated kanji script, their shellacked helmets bobbing lavender, red, pink, orange, white, yellow and black, by the tens of thousands…. They moved like a cleansing wind. Their crusade banners, proud and lofty, rode the rising breeze from bamboo poles that cleverly unscrewed, on the order of trick pool cues, into three wicked clubs. It wasn’t long before those weapons were put to practical, and violent, use…. Counterpointing the guttural incantations of the serpentining marchers, the crescendo gave one the feeling that an entire emerging generation – a generation that doesn’t give a Buddha’s damn about tradition, the Gross National Product or Expo ’70 – had lifted its voice In one cosmic, gonadal shout of rage….

– From “The Armies of the Lafcadio Hearn Night,”

the author’s fourth newsletter report from Japan.

In Japan, television and the student riots go together like rice and soy sauce, or dried squid and beer. On a rating scale of ten, the demonstrations would score at least a high twelve. And why not? They’ve got everything: drama, sex appeal, suspense, action, a kind of kabuki choreography of tactic and deployment and, above all, enough violence to sate even the most battle-hardened of video zombies.

Since 1960, when the student street armies joined the campaign in earnest, the underlying issues have been muddled while the images of the snake-dancing, wild-haired Japanese rebels, flashing across countless TV screens around the world, have remained sharply focused In the global psyche. The script, like a singing detergent commercial, became an international cliché. Masses of helmeted students, chanting unintelligible slogans and carrying signs that, to foreign viewers, might just as well have been festooned with so much seaweed, swept toward a phalanx of braced police troopers. Shards of concrete, torn from the ancient streets of Tokyo, thunked against duralumin shields. Tear gas filled the air. A psychedelic jumble of neon gave the whole tableau a nightmarish pallor. Heads would be broken. And students, Inevitably, were dragged away, like so many sheaves of rice, to police dungeons where other and perhaps more exotic forms of punishment awaited them.

It is not surprising then that in some countries the suspicion began to grow that rioting, and not baseball, had become the most popular collegiate sport in this, the Land of the Rising Gross National Product. But the confusion and dismay was not confined solely to observers abroad. Even in Japan It is hard to tell the factions without a scorecard. New groups emerge almost daily, often as splinter groups flinting off as a result of the internecine strife that has marked the student movement in Japan since its inception during the American Occupation. Organizations with tongue-twisting names like Purogakudo, Shaseido Kaiho-ha and Hansen Seinen Iinkai do not readily become household words.

And the whys are almost as confusing as the whos. Essentially the Japanese student movement narrows down to two basic zones of combat: politics and education. The former struggle has as its epicenter that nationwide campaign against the U.S.-Japan Security Treaty, which was extended this spring amid a great mass protest that attracted close to a million marchers in the major cities and prefectures. The students, of course, favor more extreme action against the treaty than do other opposition cadres, including actual invasion of American military bases. And although no two student groups are ever in accord as to strategy, most of them agree that the present Japanese educational system – a hodgepodge of American, French and German policies – is in need of emergency surgery. Basically, the students seek a broader role in running the universities. Ironically, this desire is but an extension of the somewhat traumatic and often unrealistic democratization bestowed on Japan by General MacArthur’s GHQ “brain brigade.” Resorting to strikes, barricading and blockading of university campuses, the militant students have made some notable inroads – and driven more than one professor to the insane asylum.

But out of this plethora of violence and bickering, of skull-busting and stave-swinging, of rhetoric and rough-housing, one name has emerged as the symbol of the entire student struggle In Japan: Zengakuren.

Despite the fact that Zengakuren (fully, the National Federation-of Student Self-governing Associations) since Its emergence during the 1960 anti-Security Treaty outbursts has unhorsed one prime minister, forced the cancellation of a visit to Japan by President Eisenhower, shut down three fourths of the universities in the country and shocked the Establishment out of its ceremonial kimonos, it remains something of an enigma. Lots of people know how to pronounce It, but only a few know what it’s all about.

It is reported that an American political science professor, in a surprise quiz, asked his class to identify the Zengakuren. The students’ response ranged from “A form of Buddhist religion” to “A poem by Allen Ginsberg.” Apocryphal or not, that anecdote helps to trace the web of misconceptions and inaccuracies – perpetuated in part by the world press – that have always cocooned Zengakuren.

One of the most prevalent errors is to classify Zengakuren as nothing more than a puppet of the Japan Communist Party. Although it is true that Zengakuren, which began its stormy and often violent life as a non-political movement, did achieve maturity under the wing of the JCP, a majority of its factions are now in opposition to the Party. There is throughout Zengakuren’s myriad sects a proud awareness of their higher identity with the New Left, an awareness that likewise has led them to cut most ties with the Japan Socialist Party, which they consider anachronistic and “Old Left.”

Another common mistake is to assume that Zengakuren Is a tightly knit, cell-structured organization functioning as a reflexive arm tightly sinewed to Moscow and the international communist movement. In actuality, Zengakuren is composed of a wide spectrum of left-wing units, usually at odds with each other, often shedding each other’s blood with every bit as much zeal as they exhibit in their jousts with the riot police, and always vociferous in expounding their particular philosophies. If there is any alliance at all it is the same sort of ungentlemanly agreement that existed between the free-lance samurai of olden, less complicated times. All the factions agree, however, that Japan needs a revolution. The friction arises over when and how and, less frequently, why.

Due chiefly to the ganglionized nature of Zengakuren, it is impossible to piece together a composite of the “typical” member or to accurately articulate his motivations and goals. Indeed, the Zengakuren often seems to simply be striking out blindly, trying to beat the Establishment to death with bamboo sticks and rocks.

One Zengakuren-jin at Waseda University, a young man of 21 rather highly placed in the organizational hierarchy, told me confidentially that he joined in the riots and threw Molotov cocktails at policemen simply “because it’s fun.” But for most it goes beyond mere hedonisms although of course youthful brio and adventuresomeness is certainly not lacking. Aware that Japan, while theoretically a multi-party nation, is firmly in the grip of the Liberal Democrats, the student rebels seem to feel that since they have no real political base and little prospects of achieving one in the foreseeable future they can at least make their point by fighting for their ideals. The established left-wing, relegated to a role as a sort of tolerated irritant by the ruling LDP, has proved more of a shabby uncle than the father image it might have been. The Zengakuren is disenchanted with the left-wing elders and weary of their repeated impotence at the polls.

It is axiomatic perhaps to say that the Zengakuren movement was spawned by a montage of events and moods that are peculiarly Japanese. Founded in the hectic days shortly after the end of the war, Zengakuren, like the new religions that have sprouted by the shrilling dozens, drew its first breath amid a cultural and spiritual vacuum created by the humiliation of defeat and the utter despair of day-to-day survival. Traditionally, the Japanese intellectuals adhered to the “bamboo theory.” One bends before the winds of adversity, only to snap back with renewed vigor when the storm abates – as all storms must. The militarists had been toppled and idealism, the bent but far from broken bamboo, was still as deeply rooted as it had been before the war when Marxism’s first seeds were planted in Japan. Abhorrence of war became a passion with the young. As the only nation in the world ever to feel the wrath of the atom bomb, even the thought of nuclear weapons was appalling. Yet everywhere one looked, one saw the strange faces and even stranger Ike jackets of the occupying Americans. Defeat. Humiliation. A search for identity. An instinctive craving by the young to change the old order, to challenge the feudal authority of a generation that held the reins of power in its arthritic fingers, with absolutely no intention of giving them up.

All of this, and much more, helped to shape the entire character of Japan’s revolutionary youth.

And, coincidentally, it forged that many-legged dragon that has come to be regarded as the ultimate symbol of the Japanese student struggle – Zengakuren.

Zen Nihon Gakusei Jichi-kai Sorengo – thankfully shortened to Zengakuren – came into being on September 18, 1948, in Tokyo. one of the forerunners of Zengakuren, the National Student Self-governing Union, had been set up primarily – in the first flush of Occupation-dictated democratization to establish student councils around the country, make the nation’s campuses “more democratic” and to improve student life. The drive to amalgamate the student councils was led primarily by activists, most of whom were sympathetic to the Japan Communist Party. The JCP, riding high after a series of labor triumphs, had planned a general strike of government workers for February 1, 1947. The enthusiasm was catching; the students jumped on the JCP bandwagon with whoops of youthful joy.

Enter one Douglas MacArthur. As SCAP – Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers – and in essence the real Emperor of Japan in his own palace, the Dai-Ichi Insurance Co. Building on the banks of the Imperial Palace moat, the General banned the strike. Even democracy could be carried too far.

The students were caught in the middle. Strapped by sudden raises in tuition fees, prevented by the Occupation authorities from having even a remote voice in the running of the universities and now sold short by the over-extended JCP, they formed Zengakuren.

And Japan has never been the same since.

The founding, attended by some 250 representatives from 145 universities, saw the adoption of six basic resolutions:

Opposition to the fascist-colonialist reorganization of education.

Protection of the freedom of study and student life.

Opposition to the low wages paid for student part-time work and paid by the Occupation forces.

Opposition to fascism and the protection of democracy.

Unity with the battle line of youth.

Complete freedom for the student political movement.

Within this vague and admittedly idealistic framework, Zengakuren began its stormy existence. Ties with the Japan Communist Party tightened and the organization assumed a much more militaristic, and militant, stance. In one bizarre instance, it was found that Zengakuren students who had been expelled from Shizuoka University but refused to leave the campus were being advised and led by JCP members who had been repatriated from Russia and were former non-coms in the old Japanese Imperial Army.

Gradually, amid a long series of strikes and protests, the Zengakuren and the JCP began to fall out on both political and strategic counts. In 1951, following the formulation of the U.S.-Japan Security Treaty (Nichibei Anzen Hosho Joyaku, usually contracted to simply Ampo by the Japanese), Zengakuren began the first of its many splintering phases. Changes within the upper echelon of the JCP and the emergence of the Japan Socialist Party in leading opposition to Ampo created a series of explosive schisms within the Zengakuren structure. Old leaders were kicked out. New leaders – more militant, more strongly anti-imperialist and usually more physically violent moved in.

Zengakuren now entered into what has come to be known as its “period of extreme leftist adventurism.”

Slavishly copying the Chinese Communist tactic of setting up revolutionary bases in the country and then In the towns, Zengakuren students, still under the tutelage and influence of the JCP, began infiltrating mountain villages as so-called Maneuver Squads. Their mission was to stir up the farmers and persuade them to fight the landowners. At the same time, laborers in the cities would rise up against their bosses. The Japanese Revolution would be a reality instead of a dream.

The Maneuver Squad plan brought about further factionalization of Zengakuren, Nakaoka Tetsuo, one of the defectors, recalled the “Sino-ization” period of the Zengakuren in a book titled “The Ideas and Actions of Youth in Modern Times.”

“I can never forget the summer of 1952,” he wrote “…when I saw the students secretly slipping away to join the maneuvers. Their task was to plant the seeds of revolutionary thought among the farmers who lived in the mountain villages, applying Maoism to the plight of the farmers who were viciously exploited by the landowners in the half-feudal rural society of Japan….

“…Only three days later they began to straggle back, like the remnants of a defeated army, one by one. From morning to night they had been followed by the police and forced to find shelter in graveyards and abandoned mines. With such as their bases, who would accept them, the poor strangers; they were like the beggars one is wary about helping without first taking every precaution.

“…This more than anything else served to act as a symbol of our failure and pointed to the breakdown of our ideals.”

The year 1960 ushered in Zengakuren’s Anti-Ampo periods a decade of increasingly harsh violence that culminated In the massive demonstrations and widespread arrests of just last June. By 1960, JCP-cadred student groups had regained part of their lost strength in Zengakuren, claiming about 40 per cent of the leadership.

On November 27th, more than 500,000 persons, following the lead of the Zengakuren, protested the revision of the U.S.-Japan Security Treaty throughout the nation, an unprecedented number. (Nothing like it was to be seen in Japan until ten years later, when nearly twice that number turned out to oppose the automatic continuation of Ampo)

The first major hint of the fireworks to come occurred when the Mainstream faction of Zengakuren decided they would try to prevent Prime Minister Nobosuke Kishi from flying to Washington to sign the new treaty. Approximately 700 students holed up in the airport terminal, barricading themselves against counterattacks by police. Many were injured in the wild melee that ensued. Finally, Prime Minister Kishi – protected by nearly 7,000 bodyguards – entered Tokyo International Airport by a back route and flew off to Washington.

In April, the Mainstream Zengakurens, still not appeased, attacked the Diet Building, Japan’s Parliament. Most of their leadership was arrested, and the Mainstreamers lost most of their militant fire. But other students continued to harass the Diet, wearing black mourning bands on their sleeves and shouting anti-Ampo slogans. The television crews, of course, were out in force. The medium was being massaged – and it loved every violent moment of it.

Public opinion, a moody and powerful force in consensus conscious Japan, now shifted against Kishi and his Liberal Democratic Party. Many intellectuals, serving as spokesmen for citizens’ groups, appealed to the public. Kishi’s government, they maintained, must be dissolved if democracy was to continue. The handwriting, in language so plain that even the humblest rag picker could understand it, was on the sandstone Diet walls.

In June, James Hagerty, President Eisenhower’s press secretary flew into Haneda to help set the stage for a proposed visit to Japan by Eisenhower the following month. It was a big mistake. Anti-American feeling was strong in Japan then, and the militant students were waiting for him. It was a very warm reception indeed.

Police, however, had taken precautions. As soon as he arrived, Hagerty was whisked away in a black limousine – right into the churning middle of a mob of Zengakuren hotheads. What they did to his Lincoln Continental shouldn’t happen to a destruction derby Plymouth. They rocked it. They stoned it. They bent its fenders. They sat on its hood. They sang revolutionary songs and made faces at Hagerty through the locked windows. Hagerty, enduring what had to be the longest hour and a half of his life, displayed through it all a stoicism that can only be described as oriental. Eventually police rammed through the crowd to the car, extricated the sweating Hagerty, and led him to a waiting U.S. Marine helicopter.

The Hagerty incident made front pages around the world. The upshot of it all was that Kishi, writhing and helpless in the sticky lassitude of denouement, resigned. And Ike, whose bellhop jackets graced the backs of thousands of Occupation soldiers, never did visit Japan.

The past summer, which was to be the culmination of the Zengakuren’s anti-Ampo effort (although it is misleading to talk of Zengakuren as if it were a single cohesive entity), was longs rainy and violent. But in sum the students’ snake dances and skirmishes with the police seemed a little anti-climactic, a trifle forced. It was all slightly reminiscent of the fights of Willie Pep, the old featherweight champion. A lot of footwork but very little heavy slugging.

Mr. Sato, the prime minister, is the man who fouled up the script. He is no Kishi; he possesses far more charisma and political moxie than did his elder brother. His popularity, buttressed in part by Japan’s fantastic economic upsurge (her Gross National Product is the third highest in the world), remains high. By securing the return of Okinawa to Japanese rules Sato managed to muffle a great deal of the left wing’s summer thunder, effectively clouding in the process the whole issue of the revision of the Security Treaty.

1970, however, is not over yet. It appears that perhaps Zengakuren, or at least its more activist factions, will turn their considerable numbers and energy toward demands for drastic reforms In the university system. If they hold true to past form they will home in on the questions of campus autonomy, university administration, student participation In university affairs, lack of communication between professors and students, and the influence of industry on the universities. As in the past, the national universities will probably bear the brunt of the violence, but the private universities are also likely targets.

What does the decade holds then, for Zengakuren?

Well, for one things a lot of busted heads. The number of riot police has been increased to nearly four thousand, and they have been instructed to become more aggressively “offensive” in quelling student uprisings. Detachments of Ground Self-Defense Forces are on call to supplement the police in time of troubles even in situations where the prime minister has not issued a mobilization order. It is now open season on militant students, and the riot cops are simply itching to try out their new truncheons.

…The MPD riot corps is probably the best disciplined, and certainly the spookiest looking, force of its kind in the world. They resemble something straight out of a Burroughsian yage dream. Standing behind their eye-slitted steel shields (which reach to the shoulder, since the average cop is only five-foot-five), all one can see is a tough brown face masked in a plastic visor and encased in a black crash helmet. They have no visible firearms, other than tear gas guns, but carry long kendo sticks – nasty tape-handled things effective both as a spear and as a bludgeon – at the ready. The feudal leather armor buckled onto their wrists and forearms adds just the proper samurai touch to their black fatigue uniforms. They never smile, and one has the feeling that they are the only people in Japan who genuinely hate baseball….

–Also from the author’s fourth newsletter report.

The student movements however hardly figures to diminish either through fear of physical injury or for want of fresh recruits. Within Zengakuren, of course, new factions will emerge and new alignments will be effected. The writer’s view, based only on Interviews and late-hour coffeehouse conversations with Japanese students, is that the revolutionary armies will grow, and that the government, fearing adverse publicity, will hesitate to ban even the more outrageously militant splinters, such as Chukaku and Sekigun.

Instead, it is possible that the government, operating on a much more subtle footing, will attempt either to destroy the mystique of the Zengakuren (two possible tactics would be the banning of group uniforms and outlawing of military-type training by any political group) or to lure them from the violent road of revolution onto the smoggy path of such smokescreen issues as ecology and air pollution.

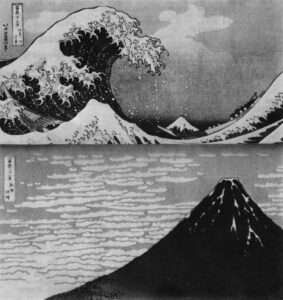

I doubt if the Zengakuren will go for it. They don’t really give a damn about remembering when one could look out one’s window in Tokyo and see Mt. Fuji rising majestic and virginal in the unfouled air.

No, their goal is revolution. And whether one likes it or not that goal, by any number of definitions if not ultimately in the political sense, has already been achieved in the Japan of the Aquarian Age.

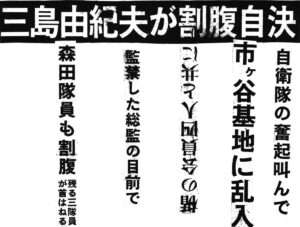

Received in New York on October 15, 1970.

©1970 Darrell Houston

Darrell Houston is an Alicia Patterson Fund Award winner on leave from the Seattle Post-Intelligencer. This article may be published with credit to Darrell Houston, the Post-Intelligencer, and the Alicia Patterson Fund.