The battered white pickup truck is bouncing across a pasture of sagebrush and alfalfa when Bronc Speak Thunder turns the steering wheel east and points to the far side of a creek bed. Scattered across a grassy slope are what appear to be a field of brown boulders — until they rise onto furry black legs and turn their shaggy heads in our direction. In another minute, the sun captures them in full relief, and we can make out the curving horns and distinctive humped backs of the American Plains bison.

Bronc turns off the engine. The only sounds are the fluty singsong of meadowlarks and the whoosh of wind across miles of Montana prairie. The thirty cows stand silent, staring at us in unison, while a dozen cinnamon-colored calves frolic around their legs.

For the calves, it’s just another day of play in a spring ritual as old as the prairie itself. But for Bronc Speak Thunder and his tribe, these animals represent the future of an epic experiment. They are offspring of the historic bison of Yellowstone National Park, the largest wild bison herd on earth and the last direct descendants of the wild bison that once roamed the Great Plains and defined the American West.

They also mark one victory in an emerging struggle to see if two endangered populations – Plains Indians and bison – can recover in unison after two centuries of devastation at the hands of European settlers. Speak Thunder’s reservation, the Fort Belknap Indian Community in north-central Montana, is one of a handful of Plains tribes that are adopting wild bison herds, hoping to rejuvenate their communities and preserve the fading culture of their ancestors while also helping rescue an animal whose history is so deeply intertwined with their own.

“Our lives ran parallel in American history,’’ says Mark Azure, who has shepherded the bison project and is now president of the Fort Belknap tribal council. “We were both run almost to extinction.’’

The tribal experiments, in turn, are part of a larger campaign by conservationists and biologists to save the Plains bison as a wildlife species and, by restoring bison to large swaths of the Great Plains, restore the region’s valuable prairie ecology. The Plains bison, or buffalo, have been described as the largest species extirpation in world history. Until the 19th century their numbers ran beyond counting – estimates range from 20 million to 75 million – and they traveled in herds so vast that pioneer witnesses describe stampedes that lasted more than 24 hours.

A century of slaughter pushed them to the edge of extinction. Their numbers, by some estimates, may have dwindled below 1,000 by 1900. Now, their restoration as a wild animal would represent one of the most dramatic species rescues on record. Their native habitat, the tall-grass and short-grass prairie that once swept from the Minnesota River to the Rocky Mountains, is endangered too. An ecological asset that has been described as matching the Amazonian rainforest in environmental value, it has been wracked by a century of grazing and plowing. Today, conservationists hope, restoring bison to large, grassy preserves could restore the lost ecosystem along with the animals.

Taken together, these efforts reflect a nascent but fundamental shift in the way Americans think about their relationship with the Earth – a repudiation of the idea that nature is something to be conquered.

“Over 150 years, we tamed a lot of wilderness and wiped out a lot of species,’’ says Jonathan Proctor, Rockies and Plains program director for Defenders of Wildlife. “Then we realized it was a mistake, and now we’re trying to bring them back.’’

Quite apart from their ecological significance, the bison projects tap into deeply-held American emotions – an affection for the buffalo as a touchstone of the nation’s past and an emblem of the rugged frontier.

“This is Americana,’’ said Cormack Gates, an international bison authority from the University of Calgary who is watching the experiments closely. “This is the history of a continent.’’

* * * *

The sun is just rising over the Absakora range at the northwest corner of Yellowstone National Park, but Stephany Seay is already on her walkie-talkie.

“Four-five, this Four-One. First Livestock truck arrived about 15 minutes ago, and a sheriff’s deputy is pulling in now. Over.’’

“Got that, Four-Five. Do you want us to stay where we are?’’

“Affirmative.’’

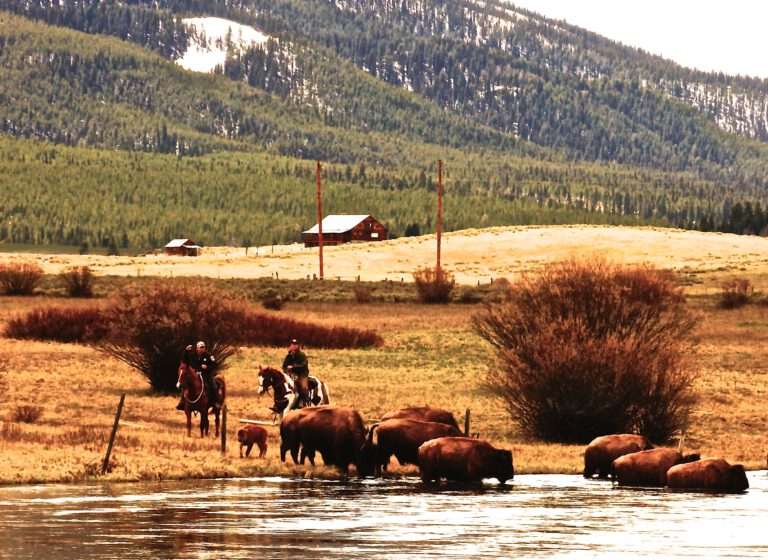

Seay is a patrol coordinator for the Buffalo Field Campaign, a group of mostly volunteer conservationists who have established themselves as the protectors of Yellowstone’s great bison herd. Early each spring scores of bison, hungry after a winter of foraging grass under Wyoming’s deep snows, wander down from the park’s high elevations to graze and give birth. Following migratory instincts laid down though centuries of evolution, they often roam beyond park boundaries. Every spring, in what has become a ritual reflecting the stubborn conflicts over land use in the American west, a team of Montana Department of Livestock employees and National Park Service rangers saddle up to haze them back into the park. And each spring for the last 18 years, the Buffalo Field Campaign has set out on mountain bikes and in SUVs, equipped with video cameras and walkie-talkies, to document the roundup – and its sometimes cruel results – while building a case that bison should be left free to roam.

This annual rite is a source of longstanding friction between the nation’s conservationists and Montana’s ranching community. But it is also a symptom of a remarkable success in saving the buffalo. In 1905, after seven decades of extraordinary slaughter, William Hornaday, a Smithsonian Institution naturalist, and Theodore Roosevelt proposed establishing a protected herd at Yellowstone, the nation’s first national park. Sheltered there – sometimes fed, sometimes left to their own devices – the bison multiplied over the decades to a healthy herd that today numbers between 3,000 and 5,000 animals.

By 1990, the herd had grown so large that its spring migration out of the park triggered a backlash among Montana ranchers and nearby landowners. In Montana, where cattle are king and gun ownership is endemic, the solution was simple: Hunters and ranchers would line up along Highway 191 near West Yellowstone and shoot any buffalo that stepped across the park boundary.

After a decade, this annual slaughter had triggered a national uproar, and the shooting came to a halt when a judge ordered a compromise among the National Park Service, the U.S. Department of Agriculture and two branches of Montana state government. Under that agreement, known as the Interagency Bison Management Plan, state livestock employees and park service rangers wouldn’t shoot the buffalo, but would herd them back onto park land, with some loaded onto trucks and shipped off to slaughter.

Meanwhile, however, the annual showdown had captured the attention of conservationists and Native American leaders across the country. Saving the Yellowstone bison became one focus in a much larger set of efforts to restore bison across the Great Plains – and a larger movement to save the prairie ecosystem itself.

Bison are what biologists call a “keystone’’ species: Wherever they flourish, a large and complicated ecosystem grows up around them. Wild plovers and buffalo birds follow them, eating insects from the dust beneath their hooves and grubs from their droppings; prairie dogs build cities where the grazing bison have cropped the grass short. Soon predators follow – black-footed ferrets, coyotes, wolves and hawks. Where bison carve “wallows’’ into the tough prairie turf – shallow depressions where they thrash about in the dust – rain collects and creates temporary watering holes for other animals and habitat for prairie amphibians. And when a buffalo dies, its carcass provides days of nourishment for wolves, coyotes, hawks and other species that could never survive without a massive mammal that converts grass into meat.

Because they are an extraordinary study in adaptation to hostile conditions, the great ungulates also began to draw more and more attention from wildlife biologists. A bison’s fur is ten times more dense than that of a cow, and provides such perfect insulation that snow will collect on a bison’s outer coat and sit for hours without melting from the animal’s body heat. Biologists use a yardstick called “lower critical temperature’’ to describe a species’ hardiness; it’s the temperature at which metabolism has to accelerate simply to keep the animal warm. For a human being, for example, that threshold is 85 degrees. For the North American bison it is estimated at 40 degrees below zero, perhaps lower. Naturalists in Canada were once trying to take a winter count of moose and wolves by flying overhead with an infrared camera that would detect warm bodies against the snow; the plane flew over an entire bison herd without picking up a signal – their insulation is so perfect that no heat escaped to trigger the lens.

While North America’s bison population has recovered dramatically in the last few decades, to roughly 500,000 animals, all but a few thousand are held in livestock herds, raised for commercial meat production. Almost all of these bison have been cross-bred with cows and most are bred for desirable commercial traits, such as meat production and docility. If bison are to survive as a wild species, the nation needs an entirely new and different effort, says James Bailey, a retired biology professor from Colorado State University and author of “American Plains Bison: Rewilding an Icon.”

“It is the whole animal we try to perceive and preserve for others to ponder,’’ Bailey writes. “We cannot preserve wild bison without wildness.’’

That’s exactly the sentiment behind projects taking place across several Midwestern and Plains states. The Nature Conservancy has established about a dozen preserves populated by bison in North Dakota, South Dakota and other states as part of its larger campaign to re-establish and protect native prairie. In Canada, the government has established Woods Bison National Park as a preserve for a related species, the North American Woods Bison. And in north-central Montana, 200 miles north and east of Yellowstone, a nonprofit known as the American Prairie Reserve is buying up and leasing parcels of land to establish a large-scale wild prairie, and has started stocking it with wild bison and other native species. And in June, the Obama administration threw its support behind the movement, releasing a report that lists 20 federal sites that would be suitable for reintroducing bison as a wild species.

But to cattlemen such as Kerry White, a third-generation rancher and a member of the Montana Legislature, these efforts sound a death knell for a life that he and his family have built up over three generations. Alarmed by efforts to expand the range of wild bison, White helped found an organization called Citizens for Balanced Use, which has filed a series of lawsuits to block the Yellowstone bison.

To White and his allies, a bison is two thousand pounds of trouble – an unruly neighbor that will wreck his fences, trample the pasture and upset his cattle. Their core argument is that many of the Yellowstone bison carry brucellosis, a bacterial disease that can cause spontaneous abortions in mammals. Even a few cases in cattle could endanger Montana’s certification as a brucellosis-free state and pummel a hugely valuable beef industry.

“We’ve got nothing against the buffalo,’’ White says. “It’s a noble animal, a beautiful animal. We just want it managed properly.’’

Bison advocates such as Proctor and Bailey point out that no case of bison-cattle brucellosis transmission has ever been documented in the field, and argue that the ranchers’ real motive is to protect valuable grazing rights they have husbanded for decades.

Nevertheless, their fierce opposition has worked. After a decade of joint management efforts marred by frequent lawsuits and factional warring, the interagency bison group made little progress in finding a safe zone for the bison to graze outside Yellowstone. And the annual hazing ritual continued. Then, about a five years ago, a coalition of wildlife groups asked what to them was an obvious question: Why would you slaughter or haze animals that are widely loved and represent the world’s last surviving gene pool of what was once North America’s greatest mammal?

In 2010, the conservation groups appealed to Montana Governor Brian Schweitzer. Schweitzer comes from a family of cattle ranchers, but he was also a Democrat with abiding respect for Montana’s Native Americans and the nation’s conservationists. Schweitzer proposed a solution to the brucellosis deadlock: A sample of bison from Yellowstone would be held in quarantine just outside the park and tested regularly for brucellosis for three years until proven healthy, and then turned over to the conservation groups for the establishment of new satellite herds outside Yellowstone.

The Park Service established a special pasture just north of Yellowstone, but when the first group of bison were ready, it wasn’t easy to find willing hosts. Managing a herd of wild bison requires a large expanse of prairie, a significant investment in fencing and a certain amount of bison expertise. CNN magnate Ted Turner, himself a major landowner in the West, was the only person to take the first generation of quarantine animals.

Then Proctor had an idea: Who on the Great Plains has large swaths of open land and a longstanding interest in the survival of bison? A second round of bids went out, and in 2011, the Fort Peck and Fort Belknap reservations in Montana – which had run tribal herds with bison from other sources for more than a decade – stepped forward with proposals.

“We had the land. We had experience with a bison herd,’’ said Azure. “And we have a historical connection to the buffalo.’’

In March 2012, the first truckload of quarantine bison arrived at the Fort Peck reservation; in 2013, after another bitter year of litigation between ranchers and conservationists, the Montana Supreme Court said the experiment could continue, and a caravan of bison arrived at Fort Belknap from Fort Peck.

“There were crowds of people lined up along the highway and in the meadow,’’ Azure recalls. “I wasn’t expecting anything – I was just exhausted by the long battle and relieved that we made it. But we came over the hill and into the pasture – they burst into cheers and applause.’’

Azure, who had spent hours, days weeks at the Montana Legislature lobbying for the bison experiment and even had to convince some members of his own tribe, takes a quiet satisfaction today. So do others in his community. Ray Gone, a Fort Belknap businessman and the reservation’s tourism director, says the bison are already improving the prairie ecosystem in their rolling pasture. Wild plovers and cowbirds have returned, and native grasses are sprouting here and there. Prairie dog colonies are springing up where bison have cropped the grass short, Gone said, and hawks are swirling overhead. “It’s changing our land in ways I haven’t seen since I was a boy,’’ he said.

At nearby Fort Peck, wildlife manager Robert Magnan echoes the sense of stewardship: “For hundreds of years, the bison kept our people alive. Now it’s our turn to save them.’’

This year, about 100 Yellowstone bison from Ted Turner’s ranch will become available for new homes, and the state of Montana is taking proposals. Fort Belknap will request a second batch, but finds itself competing with major conservation groups such as The Nature Conservancy and well-funded nonprofits such as The American Prairie Reserve – all eager to give the animals a home.

Azure sees that as a victory that goes well beyond his tribe.

“I’d like to think that we should be first in line,’’ he said. “We have the history and the experience.’’ He pauses and glances out the window. “But these animals belong to the American people.’’

David Hage and Josephine Marcotty, both of the Minneapolis Star-Tribune, are examining the fate of the Great Plains bison during their APF fellowship.