Globalization is hardly a new force affecting India. To think so is to ignore a diverse and pluralistic long-standing civilization that was shaped by a long list of “invading” (globalizing) cultures that became what we now know as India. The previous globalizers of India include the Aryans, Hindus, Dravidians, Greeks, Buddhists, Turks, Afghans, Scythians, Muslims and most recently, the Europeans, Portuguese, French, Dutch and finally the English. One has to understand that as India has been globalized it has also been a globalizer too, with millennia of colonialism across Southeast Asia, with temples like Angkor Wat left behind as a reminders of India’s one time presence.

Long viewed by the West, as “poor and impoverished,” to its neighbors such as Sri Lanka, Bangladesh and Pakistan, India is wealthy and powerful. To these smaller neighbors, India is a great power, a globalizer of its own, which expects deference from them and is sometimes angered when those nations downplay their Indian lineage. They prefer to play up their own local cultures, which are frequently hybrids of the larger Indian culture and their own indigenous ones.

India, knowing its past as a globalizer, sees itself as one of the great nations of the world. But today, India has yet to build on the onetime greatness of its civilization to earn international influence and respect. India sees itself as equally important as Russia, China and the U.S., believing it has much to offer the rest of the world. Historically this has a basis since important aspects of trigonometry were developed in India, as was the decimal system, which, was later taken from India by Arab mathematicians, and on to Europe in the 10th century, only to come back to India through books from the West. Similarly, at the start of the 18th century, India was a major economic power with 23 percent of the world’s GDP according to some economic historians and over 25 percent share of the global trade in textiles. By 1995, this had declined to less than 5 percent of world income and less than half a percent of world trade.

The most recent wave of globalization affecting India came with the British who were important to Indian development, in positive and negative ways. The British consolidated a land of many separate regions and kingdoms into what we know of as modern India. While the British exploited India’s population, economy and resources as colonial rulers, they also left India, after two centuries of rule in 1948, with democracy, laws, a judiciary, and a free press, 40,000 miles of railroad track, canals, and harbors. English as the language of Indian business and the English language schools are arguably some of the most important remnants of the British, giving India a linguistic global gateway not found in former French, Spanish or Dutch speaking colonies.

Another British relic is cricket, which has largely displaced local games in rural areas, in both Nepal, a land not known for interest in cricket and in India. The place of cricket in Indian life exemplifies a unique aspect of “Indian-ness,” the ability to absorb outside influences and to transform them through a peculiar Indian magic into something else that becomes a natural part of India.

The experience of McDonald’s, one of the ultimate globalizers, illustrates the idea of Indian adaptation to globalization. While McDonald’s can boast of selling billions of hamburgers worldwide, they have not done nearly as well among the one billion Indians. In deference to local religious sensibilities — and finicky taste — the burger giant has radically revised its lineup. Since Hindus avoid beef and practicing Muslims do not eat pork, only mutton satisfies religious restrictions and thus the Maharaja Mac was born. It is considered too bland for the taste buds of some consumers in the land of hot curry and sharp Cardamom. McDonald’s struggle in India makes it one of a number of fast food companies that despite such troubles, has an appeal as foreign food, conferring status on the flush with cash Indian middle-class.

The former globalizers that came with invading armies have increasingly been replaced by less violent but equally powerful globalizers. Television is arguably the most dominant gateway of globalization affecting India today. While TV was launched in India in the late 1950s it only became widespread in the 1980s, after the governments ended their monopoly as the only broadcaster. Satellite TV arrived in 1991, bringing with it Indian versions of MTV and later “Who Wants to Be a Millionaire?” Because of the abrupt end of the monopoly of the state channels, the instantaneous arrival of satellite TV has been more disruptive and far reaching in India than elsewhere in the world. According to reports, traditional dress is increasingly displaced by Western dress seen on TV. In the southern state of Kerala, a study showed that teenage abortions rose by 20 per cent in a year, as teenagers feel pressure to have sex, purportedly due to the explosion of sexually explicit imagery from sources like MTV and the Indian equivalent channels.

Another example of TV’s globalization in India can be seen in how India globalizes neighboring nation’s media markets. While English may be perceived as the dominant language of TV, in South Asia, India’s Hindi is TV’s dominant language, transforming neighboring countries into little more than passive recipients of Indian Hindi TV and displacing local languages like Bangla in Bangladesh and Nepali in Nepal. Increasingly, local languages, inside India and across South Asia fade under attack from Hindi as Indian film and sports stars are made as familiar to Bangladeshis and Pakistanis as they are to Indians.

The other way TV globalizes is in how it helps keep NRIs (Non Resident Indians) in contact with their culture of origin. These people, who are of Indian origin (and are also derided as Not Really Indian) make up the great Indian Diaspora, an estimated 15 to 21 million people spread across the world who are often better educated than the dominant populations they live amongst. NRIs are the third largest direct foreign investors in India after the U.S. and Britain. They stay in touch with India by viewing regional language in their homes across the world. Subhash Chandra, founder of the most famous of these channels, India’s Zee Television, offers the popular Indian cable channel in many parts of the world. Similar globalization occurs through the spiritual gurus, whose discourses are available to the Western and Indian global community through cable TV and the Internet. Similarly, Indi-pop music is the fusion of Indian popular music with Western rhythms that first emerged among Indian youth in England and then successfully traveled back to India.

Likewise, Westerners and NRIs have rediscovered classical Indian music, which went global a generation ago at the time of the Beatles, with Ravi Shankar and Ali Akbar Khan. Today is has become big business as some classical musicians devote a third of their time to overseas concerts. With globalization’s economic and communications revolution, Indians abroad (and increasingly their Western friends and neighbors) feel closer to India than ever before with a growing appetite for things Indian. The explosion of interest in Indian cinema, known as Bollywood film, is prominent particularly in the U.S. and the U.K. The thousands who similarly come to India to study Yoga, Buddhism and other important under appreciated aspects of Indian culture highlight the fact globalization is more of a two way street than most people realize.

To understand the NRI community in America, note that Indian immigration to the United States has been particularly related to the high-tech sectors. Until recently, about 25% of the graduates of India’s four most prestigious technology institutes immigrated to the U.S. This has lead to a situation where more Indian technological talent is in the U.S. rather than India. Business Week reported that an extraordinarily large number of enterprises in Silicon Valley–more than 30 percent–were started by Asians, with the overwhelming number being Indian. Some argue that the globalization of this migration was a way for talent to find opportunities. The argument goes that some Indians were already more ambitious and hardworking than their compatriots back home, but they often saw their efforts being obstructed or under valued in India.

Though even this is changing as NRIs, in some ways the ultimate globalizers, who alter India when they return with western goods, values and spouses, are returning to India to run for election there, starting on local levels, promising to apply the expertise they learned in the West. The prominence of NRIs in America and the West is growing rapidly as seen when Pulitzer prizes, Nobel prizes and other important awards are increasingly bestowed upon Indians, in India, the US and across the world.

While India clearly has access to important gateways of globalization, such as well-established channels of media and commerce, it also has its own unique, large NRI community, a large and potentially important gateway of globalization. The ultimate question is whether these gateways of globalization will bring real progress and modernity to India. While India has some characteristics of modernism one can not yet call India modern. Modernity is not just Westernization, with Japan being a modern country that has its on values at its core rather than Western values.

In classical social theory, modernity increases the credence given to status of education or other merit based achievements while it reduces the credence given to birth status. The psychological concept of intersubjectivity, the ability to empathize with and share in another’s plight and fate, is at the heart of modernity and lacking it, many argue modernity in a society degenerates to crass commercialism. Likewise, if consumer items remain in the hands of the few rather than being disseminated among the many, such a society has the visible signs of modernism but not the ideological underpinnings. Some ask if the caste system, which came to India through previous invaders, the Aryans, will continue to keep the different classes divided or will modernism’s system of meritocracy finally tear caste’s walls down? Only time will tell if India’s gateways of globalization will spread ideology and not just consumption throughout the Indian subcontinent.

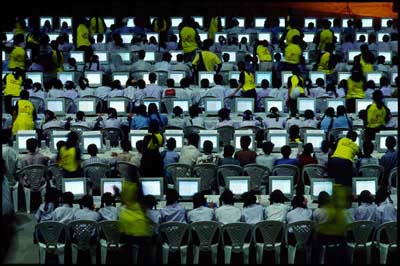

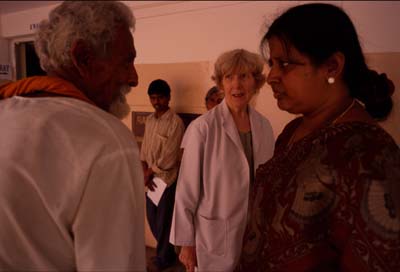

Photos