Photos and Article by APF Fellow Dorothea Jackson.

It is spring and along the Daniel Boone Parkway, between London and Hazard, Kentucky, yellow wildflowers bloom from the fractured stone faces of mountains that have been dynamited open for the passage of the road. From ditches kept watered by the seeping rocks, peep-frogs sing earth’s oldest, shrillest evensong to passing travelers.

Beside small streams the willows come awake in neon green. Tiny cemeteries dot still-bare woods on the hillsides, bright with those botanical wonders known to florists as “permanent arrangements.”

Under these memorial sprays of wilt-proof pinks and lavenders and reds lie two centuries of stories of what it took to get into this hard, high land, and what it took to stay.

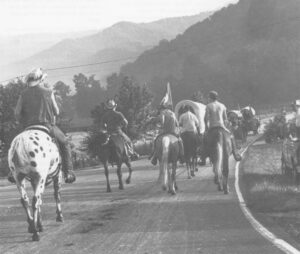

Here, the influx through Cumberland Gap began in earnest in 1775, behind Daniel Boone on the Wilderness Road. Other processions were moving down the valley of Virginia from Pennsylvania and up the rivers front coastal Virginia, Carolina and Georgia.

Whatever pioneers were looking for, they found mountains after mountains.

From Virginia, west beyond the Blue Ridge the geologically-younger Alleghenies and Cumberlands rose like the jagged walls of a fortress. While the weather-whittled hearthstone of the Blue Ridge predated life on earth, in their gestation these younger ranges had known ancient palms and ferns and bogs. What lay in pockets deep and wide under their scant soil was coal.

In North Carolina, like crossbars between the two great parallel ranges of the Blue Ridge and the Unakas stood such sub-ranges as the Blacks, the Balsams, Nantahalas and Snowbirds. For two hundred miles, east to west, over western North Carolina mountains rolled.

Out of the mountains rivers flowed. In the industrial age that would disrupt the largely-agrarian visions of these settlers, Carolina’s water would be Kentucky’s coal.

Rivers facilitated settlement. Sometimes. The rich valleys such as flanked the James, Potomac, Shenandoah, New River, the Holston, Clinch, Catawba and the Little Tennessee afforded at least some leisurely passage and incomparable homesteads.

The immigrants’ small craft embarked upon any stream that appeared even marginally navigable. Tow paths soon wound beside the deeper rivers to afford mule or oxen-powered movement upstream. Along stretches of rapids, visionaries designed canals with locks to make river commerce swift and smooth.

What was given, of Course, could unpredictably be swept away. Several times, most recently in 1936, the Potomac rose and devastated the historic town of Harper’s Ferry, West Virginia.

In 1916, the Catawba burst its bridges between Old Fort and Charlotte, North Carolina and started, among other more tragic and horrifying flotsam, a string of boxcars and a whole cotton mill on their way to the Atlantic Ocean. From that same deluge, untold bridges, houses, barns, livestock and at least one locomotive lie in the embrace of the French Broad River. No one will ever know how many people died.

Streams led the way for many through the Blue Ridge. But not without frustrations. A barrier stretching 800 miles from Alabama into Maryland, the front wave of the range looks down two to five thousand feet upon the gently-rolling piedmont.

Rushing out of these highlands, rivers plunge wildly down narrow gorges and over precipitous escarpments. At one point at the North Carolina-South Carolina line, Whitewater River falls in two major cascades that total over 800 feet.

Not that these impediments halted settlement; the newcomers just walked or drove their oxen up the hills and over.

Clarence Lusk, who lived most of his life almost close enough to hear the river roar, remembered an incident on the dirt road that used to pass right over the brow of upper Whitewater Falls.

A neighbor was coming down that track one cold January day, and just as his wagon approached the top of the falls, one of his steers slipped on the ice and went over. Wisely, the driver jumped out the other side. The steers went down, wagon behind them, smashing to splinters as it went. But miraculously, the steers met with a ledge and survived.

“He went and threw feed down to ‘em everyday,” Lusk said. “They weren’t hurt only their horns were broken off.” When at last the ice melted, rescuers climbed down and roped the captives out.

Those undaunted by such terrain, who crossed into uncharted coves and valleys, who made their way among understandably disgruntled native peoples and set their heels firm in the Southern mountains were not, by and large, a dainty folk.

Yet thousands who survived the rigors of that migration would later die prematurely of the killers of the times–typhoid, pneumonia, smallpox, tuberculosis. Women died in childbirth or afterward of childbed fever.

Gravestones bear witness to the dignity of the survivors’ grief, as in this tribute to Sallie Johnson, who was buried in 1853, at age 20, in a churchyard on Keowee River in South Carolina: “Early, bright, transient, chaste as the morning dew, she sparkled, was exhaled and went to heaven.”

Children died of diphtheria, whooping cough, mule-kicks and measles; whole families succumbed to obscure plagues such as “the milk-sick,” a milk-borne poison from a plant consumed by cows in shady woodlands.

Men died in accidents, or not uncommonly, of disagreements. The latter peril persisted far past frontier days in a few localities. An elder lady showing a visitor around her off-the-beaten-track community in western North Carolina observed, in passing the local cemetery, “Not a single man that’s buried in there died a natural death.”

Peculiarly to the coal fields would come more contemporary dangers. Kentucky writer Harry Caudill recorded that in Harlan County alone, by 1986, more than 1,200 workers had been killed in the mines. Nationwide, by 1977, mining deaths had passed 121,000.

Doctors in the remote hills were a varied lot before stern modern laws took hold. Some were medical college graduates who chose so rural a practice because it suited them. Mining and timber companies brought in excellent physicians who were a Godsend all around the countryside.

Others, wise perhaps in the uses of roots and herbs, practiced medicine as a somewhat arcane trade. Unflappable midwives called “grannywomen” commonly presided at birthings, often staying several days to manage the household after the baby was born. One thing was almost certain: no one practiced medicine long without a fight if his or her remedies consistently failed to bring relief.

Dr. Parker Ford, who made house-calls for many miles around the community of Grassy Fork, below Newport, Tennessee was likely the last of a breed when he quit practicing, officially, in 1977, two years before his death at 96.

Ford, a brilliant lover of poetry, dapper and handsome to his last days, had bypassed medical school. In his youth he apprenticed himself to a timber company physician, and “read medicine” as attorneys once “read law.”

By last count, he had assisted at the birth of 2,000 babies. Faced with illnesses and traumas, he could turn no case away, even when, as he said, “I didn’t know what I was going to do.” He told of a father riding to his house one afternoon to get help. The man had come many miles; his teenage daughter had stepped into a broken culvert pipe and had nearly severed her leg above the ankle.

“They lived way across the mountain,” Ford said; “It was night when I got there.” He had nothing to kill the pain. The calf muscle and ligaments, cut at the hamstring, had “rolled like it was on a spring” up the back of the girl’s leg. Using a surgical needle and strand of catgut, he fished for the severed ends, pulled them back in place and stitched them, closed and dressed the wound and bid the family farewell.

“I didn’t see that girl for 20 years,” he said. “Then one day I was in town and a married woman came up to me and said, ‘Look! Remember me?’ She turned around and showed me the back of her leg. There was the scar. But she didn’t even limp.”

The state turned its head while Parker Ford practiced, sans diploma. Not only was there no one better to bring care to his people; there was no one else. When he was 94, the state built a public health clinic near Grassy Fork so he could retire.

All across the mountains, the universal story of country doctor has been much like Parker Ford’s. With few exceptions, the venerable breed has become extinct.

“Rural health is not profitable and not glamorous,” says Susan Walter, executive director of the Shenandoah Community Health Center in Martinsburg, West Virginia. The Shenandoah Center serves 10,000 clients in three counties with a staff that includes three physicians and five nurse-practitioners, one of them a midwife.

To lure practitioners into communities that need them, West Virginia has begun a program in which the state pays off the education loans of medical school graduates and midwives who agree to serve for a specified time in rural areas.

Some small hospitals have had to close, not because people do not need medical care but because, increasingly, medical professionals are scarce and technology costs money. The frying chicken or the watermelon that paid Dr. Ford will not cut it in this new world.

And yet, remnants of the “old” persist among the coves. In the spring of 1989 J.D. Chappell, a life-long handyman in the serenely self-contained Eastatoee Valley of Pickens County, South Carolina, went to town to see a doctor.

J.D. usually walked the 15 miles to the town of Pickens, collecting aluminum cans along the way to bolster his slim budget. This time a neighbor had to take him. The problem, the doctor leveled, was a brain tumor. The outlook was poor. Treatment had to be radical and immediate.

Painful and futile was the way J.D. read it. He was without close family or insurance. At 64, he was one year short of Medicare. Being supremely at peace with the cycles of the earth, he chose to die at home.

So for eleven weeks, an organized corps of neighbors up and down Big Eastatoee Creek brought in meals, cleaned his little cabin, stayed at his bedside around the clock and fed and bathed him when he could do these things no longer. In August, they mourned his passing.

Only in the funny papers has the life of the Southern Highlander been “simple,” an idyll of carefree repose with gun and jug.

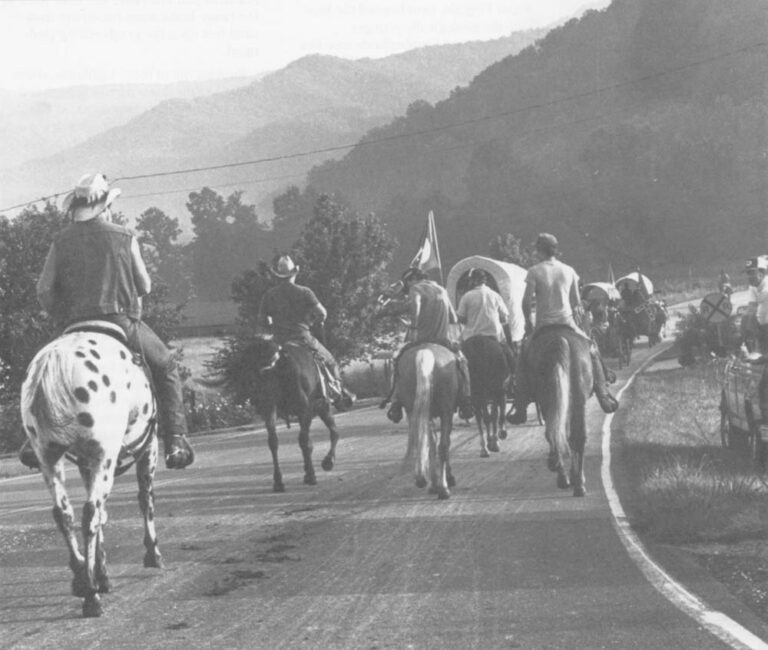

Most–though not all–primary highways are now paved throughout the Southern highlands. Road construction and improvement are expensive and often problematical; earthmovers literally move mountains to make new highways possible. The wise bear still goes over the mountain but human traffic more often goes through, in blasted canyons, or under, through tunnels.

By nature, this deceptively fragile land does not always cooperate. Bob Crisp, a North Carolina Division of Highways engineer, recalls a monstrous rockslide four years ago that for several weeks blocked Interstate 40 at the mouth of a tunnel near the Tennessee line.

“Nobody was hurt,” Crisp says; “I don’t know how it didn’t kill a week’s burying of people, but it didn’t.” The rebuilding costs were “colossal,” he says.

All across the highlands, emergency vehicles from county seats 20 miles or twice that far away share precipitous two-lane roads with creeping tractor trailers, farm machinery, school buses and terrified flatland tourists.

School consolidation, beginning in the 1940s, put thousands of buses on the roads. Sixty-mile round trips to school are still part of some mountain children’s day. The demise of the one-room, all-grades school where the morning bell echoed off hills for miles has had many and mixed effects, not the least the displacement of the centers of community.

Too rapidly for some, too slowly for others who want, principally, a better choice of jobs in a land where development and industrialization bring peril along with promise, things are changing.

A dozen years ago, Thomas Campbell of Buladean, Mitchell County, North Carolina leaned on the hoe he had just made, a hand-whittled handle fitted to new-forged blade, and looked back over his personal hundred years.

There were some “constants.” His bright blue eyes were sharp enough still that he could read the Bible every day without wearing glasses; he worked each day making tools, which he sold in shop, and farmed his 14 acres.

There was but one thing, though, that in his mind set Thomas Campbell, at 100, quite apart.

“I know,” he said, “that there’s people telling you all the time, ‘Oh, I remember the first automobile I ever saw.’ Well let me tell you – I remember the first horse I ever saw. And I was grown. We come into these mountains with sleds drawn by steers. That’s all the way we went. This land was too rough for a horse or a wagon.

“Lady,” he said, “you are looking at a man that has lived from before the wheel to putting a man on the moon.”

During the last four decades of Thomas Campbell’s lifetime, the exodus of the young and able from his homeland swelled and hit its peak. The going out was physically, at least, a far cry from the coming in.

As money has become the medium of solving problems that early settlers didn’t know they had, ingenuity often has become the ticket for survival.

Under his striped tent on the roadside at Vicco, Kentucky, thirty-year-old Loren Whitaker sells fudge. Five days a week, he makes fudge; weekends he sells to a brisk trade.

Why fudge? “Coal is about all there is here now. I just didn’t want to work in the mines.” Whitaker knows, he says, that if he wanted to leave here, with his college education, he could find a good job.

But, as his wife Debbie, who is on the staff of a nearby community college, says, “This is home. This is where our family is. There is no place like these mountains.”

©1991 Dorothea Jackson

Dorothea Jackson, a freelance writer, is examining the economic conditions of the Southern Highlands.