Photos and text by APF Fellow Dorothea Jackson

The Old South Carolina highway that snaked through the first wave of the Blue Ridge Mountains ends now in Lake Keowee. Literally, just short of where a covered bridge used to span the formidable green torrent that was Keowee River, the crumbled blacktop now descends into depths of aquamarine.

As the farms and timberlands were being leveled in the 1960s for the two-dam Keowee-Toxaway hydroelectric project, a new Scenic Highway 11 was built three miles south.

For a long time, then, after Duke Power Company closed the floodgates on the river in 1968, and after traffic began to cruise smoothly over the long new concrete bridge and speed-tolerant new road, far back in the woods one could walk the old road’s yellow center line out into the clear lake water, deeper and deeper.

Few adventures were more surreal, more other-worldly (or more chilly) than a barefoot hike as deep as one dared go. On the road that used to take its sweet time winding down to Grandma’s, in this new age fat, pearlescent minnows nibbled at one’s toes.

It was too weird and popular to last. Beleaguered lakeside neighbors threw up a barricade after years of calling the law to haul out cars that kept on rolling down the road toward Meaningful Experience, usually occupied by persons seeking thrills even more psychedelic than the kisses of small, moon-colored fish.

That old road of course was not the only thing that ended with the lake. Across the Southern Highlands, the continuing push for cheap hydroelectric power that could be marketed far away began early in the twentieth century, and since has shadowed many a populous river valley with the threat, if not the fact, of social rupture.

On Keowee, broken with the old highway was the link of community that for well beyond a century had joined the valleys on either side. Families whose lands were not flooded by the lake still faced an eight or ten mile trip, by way of new road and new bridge, to see over-the-river neighbors and kin they once could holler to.

The Eastatoee Grocery closed, cutting off the only nearby source of cold drinks and loaf-bread, candy bars and gas. For a while, until a new crop of folk descended upon the valley, tendrils of kudzu licked threateningly at the severed length of road.

Yet in truth the outmigration from this rustic, stream-washed paradise started long before the dams were ever mentioned. The post office, called “Nimmons,” was long gone: the railroad that took cars of huge logs off of the mountains had been riddled and twisted in a flood in 1928, and never was replaced.

The Methodists had long since abandoned the valley to the Baptists, leaving behind the little white frame McKinney Chapel that once served also as the school and survives, now, for the principal community event: the world’s most unaffected Christmas pageant.

The lure away from here was jobs. Money. Those were matters of little consequence two hundred years ago, when white settlers surged into mountain lands fast on the heels of the departing Cherokees. But then those people pulled their own teeth, brought their own babies, paid no income tax.

Furber Whitmire, displaced by the lake from his Keowee River farmland, was 96 when asked to share a memory of his lifelong neighbors.

Back before everything cost money, he answered, people very well took care of themselves. The river yielded trout and “blue cats,” his personal favorite. The fields and woods provided game. “Public work,” he went on, was something most eschewed in favor of nearly total fiscal independence.

“Those people all lived at home,” Whitmire said. “They growed their living. They growed their hogs and cattle and their corn.”

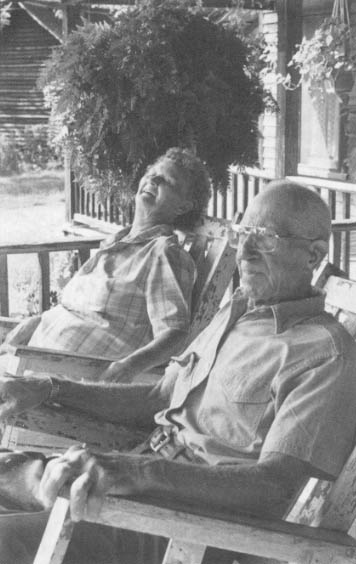

A descendant of Whitmire’s self-sufficient neighbors, Paul Bowie still lives at home, with his wife Mildred, in the eloquently rambling, roomy and unpainted Eastatoee Valley farmhouse where he was born some 80 years ago.

As Bowie himself would do later, his father taught school, raised a lot of corn and a few acres of cotton. Cotton was not a mountain crop but Bowie the elder found it could be petted into producing enough cash to buy the family’s shoes and cloth to make their clothes.

“He ran a store in one room of the house, the same room where my mother ran the post office,” Paul reports from the comfortable station of a rocker on the long, long porch. The rising moon is shining through a big old hemlock tree; pauses in the memoir are filled the chirr of evening bugs and the rustle of a mountain breeze bearing the scent of creek-damp earth, new hay and honeysuckle.

“He made a little off of coffee. It came by the 50-pound bag; some of it came roasted and some of it green. People’d buy the green and roast it in their oven. Most everybody had their own little grinder.

“And in 1910 my daddy was the census enumerator. He kept his little badge that said, ‘Census 1910.’ We raised sorghum cane and made syrup. ‘Course we raised hogs. The only beef we killed was Jersey calves: we’d kill a couple of calves in October or November, and we’d dress ’em and put ’em in the wagon on a clean white sheet with another clean sheet on top of ’em, with a meat saw and a butcher knife, and we’d go down the road.

“We’d stop and ask people if they wanted beef. If they did we’d cut ’em what they wanted, weigh it on a little scale and take 15 or 20 cents a pound.”

Money was a novelty. So was the idea of leaving the valley to earn it. “Buddy and Mack Reeves, they were the first ones I can remember,” Bowie says. “They went down to Easley and got a job in the cotton mill. I don’t know when that was, but it was when they drove a Model T Ford and it ran on red top Fisk tires with red inner-tubes. Then Henry Bowie moved to Easley, to work at Glenwood Mill…”

The exodus had begun.

The two world wars had a profound effect, as young men saw for the first time the lands and opportunities beyond the mountains. Some married outland girls, took outland jobs. Some were rather like a cousin that South Carolinian Ben Robertson wrote of in “Red Hills and Cotton,” a youth of the hills who took a drink before church, got possessed of a certain spirit, went to the crossroads and hitchhiked all the way to Macon, Georgia.

“I went to cafes and picture shows,” the penitent young man later confessed. “I like that sort of life.”

The coal mining sections of Kentucky and West Virginia would suffer their most massive population losses later. Harry Caudill noted in “My Land Is Dying” that “between 1950 and 1960, entire communities in Appalachia were all but depopulated as men, women and children climbed into their old cars and headed for a new life in Indianapolis, Cleveland, Detroit or Chicago. The population of Leslie County, Kentucky fell from twenty thousand to ten thousand in those ten years; in Harlan County it dropped from seventy-six thousand to thirty-five thousand.”

Because the population of the more southerly highlands was diffuse and almost wholly agrarian, the visible impact of out-migration was less dramatic. And it peaked earlier, as ruined land and a farm depression that preceded the 1929 Wall Street crash by nearly a decade sent a flood of the young and able to the textile mills of the Piedmont.

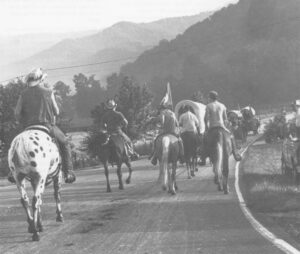

During the Depression, travel on such narrow dirt and gravel roads as served for mountain highways (and in a few instances still do) was made the slower and more perilous by feral stock, from mules and hogs to roosters, that simply had been abandoned in the flight to the mills of Greenville and Gastonia.

It was sometime around 1920 that Bertha Meece’s Aunt Delphie left the family’s Transylvania County, North Carolina home and went to Pickens, South Carolina to work in the mill.

“When we were little we used to make a playhouse in the chimney corner. I was the oldest; I was always the doctor,” she says. “I’d boil some peach tree bark, grape vines, all kind of things in an old rusty can in the fire. Then I’d give the other children a spoon of it for the toothache or the stomach ache. One night after I’d give ’em a terrible, bitter dose they all got sick and started to vomit. They all about died!”

The only “doctoring” people got on the ridge where her parents raised their dozen children was herb medicine. With a few discomforting trials and errors, Miss Bertha learned herbs from her father.

Though she won’t call herself an “herb doctor,” as those so close to the earth used to do, people still come to her to get a little dried offering of bloodroot (sore throat, sore gums, poison oak), or yellow-root (throat and digestive complaints) or snakeweed (snake bite, spider bite, hemorrhage and stings) from the muslin sacks that hang on the kitchen wall of her house near Table Rock, on the South Carolina side.

“It was so steep over there where my mother and daddy lived,” she says, “that when they’d take me to the field with them, when I was a baby, they’d dig a little hole to set me in so I wouldn’t roll off the mountain.”

What did the family do for money? “My sister and I dug grub root to buy the cloth to make our clothes. It was a little small plant about the size of lettuce and I believe they used it to make that female medicine, ‘Wine of Cardui.’ Mother made every bit of our clothes and she sewed for other people. Sewed the quickest, with her fingers. Never had a sewing machine.

“We would all hoe corn for 50 cents a day. We had plenty of land but my daddy never had to pay taxes. He worked on the roads. You could work on the roads to take the place of taxes. Really, we didn’t worry about nothing back then…”

It is hard to say exactly when the worrying began.

For Fred Weaver, who lived nearly all of his 100 years on the New River at Piney Creek in Allegheny County, North Carolina, it began in the early 1940s after his son, just out of college, developed an abscess on the brain.

“He laid in the hospital six months. And then he died,” Weaver said. During that illness, Weaver spent much of the time by his son’s bedside while the 260 bottomland acres of the ancestral family farm languished, unworked. For the first time in his life, Fred Weaver found himself in debt.

“For the first time, I had to go to public work. I had to leave home. Oh, I can’t tell you how that hurt me, to leave home. I went over to Fontana, where they were a’ building that dam. I was gone four years, but when I come back home, I didn’t owe one dime.”

For many a mountain widow with young children, economic anguish began the day she found herself bearing, alone, the crushing physical burden of her family’s survival. No wonder she gathered a scant bundle of belongings and herded her brood onto the cotton mill’s labor-scouting wagon or rickety truck, when its rasping clarion sounded at her gate.

Such promise did that journey hold, for the thousands who made it. Manly Wade Wellman recounts in his book “The Kingdom of Madison” the arrival in Madison County, N.C. of a New Englander named Thomas Robinson Dawley, Jr., a federal bureaucrat sent south in 1907 to study the wisdom of permitting child labor in the textile mills.

Study seems hardly to have been the object. “He applauded the hiring of children at 40 cents a day,” writes Wellman, “reasoning that a family with several young earners could live more comfortably than on a remote farm; and he came to a deep philosophical conclusion:

“‘Were I a Carnegie or a Rockefeller seeking to improve the condition of our poor mountain people, I would build them a cotton-mill. I would gather their children in just as soon as they were big enough to doff and spin, and instead of feeding them on homilies and panegyrics, I would pay them a stipend that would bring them more than “bread and meat.” I would teach them with real money what real money brings….'”

As eight-year-olds were sweeping lint from cotton mill floors, in the Piedmont, and their only-slightly-older siblings were doffing and spinning from before dawn till after dark, the people of eastern Kentucky and West Virginia were learning their own harsh lessons about what “real money” sometimes cost.

As elsewhere in the highlands, timber-buyers combed the Cumberlands and Allegheny’s, offering landowners rarely as much as a dollar apiece for massive, virgin hemlocks and poplars. That sounded like a lot until the land was nothing but stumps and gullies and the “fortunes” were all spent.

Later the generous buyers came for mineral rights. Often, through indecipherable deeds, mining companies based in far-removed cities claimed for themselves the right not only to mine the underground–harmless enough, from a farmer’s point of view–but to scalp from the land with strip-mines the trees, topsoil and pastures, even the tiny cemeteries.

Nearly everyone has long agreed that new industry, new business, new jobs are desperately needed for mountain people trying to live at home, and some enterprises that have come in are exemplary citizens.

Yet a few bad apples, some of them large enough to hold a wide-spread job base and local economy as hostage, have fouled clear rivers, spewed stench into clean mountain air or strewn toxic wastes over the landscape.

Plainly, bigger is not always better when it comes to industry in Southern Appalachia. It may well be that the future, like the pioneer past, lies in the hands of individuals, or those who think “small,” and with great care; entrepreneurs who live at home, hire at home, keep the profits at home, and at the base, take care of home.

Increasingly, they are here, at work. The Appalachian story of this decade may be theirs.

©1991 Dorothea Jackson

Dorothea Jackson, a writer in Six Mile, South Carolina, is focusing on the economic conditions in the Southern Highlands.