In the last three months of her life, Christine Skubis Whitman passed through the layers of dying from the AIDS virus in much the same way a newborn infant learns to live.

She had regressed to baby steps, which she attempted only with the help of the able-bodied propping her on each side. At first, the loss of control had her seething. Later, when that limited mobility deserted Chris and it came time for adult diapers, there was a defeated acceptance, then ceding of control, and finally, a defeated indifference. It was a shocking change in a woman once noted for her ability to catch the spotlight.

Just after New Years Day of this year, she retreated into the fetal position on a pink-mattressed daybed, one of the prizes wangled from a local charity for her twin daughters, Megan and Melody, also infected with the virus. Chris’s last defiant act had been to move into that bed where Megan had spent her last weeks the previous summer before dying of AIDS. Chris rejected the rented metal-framed hospital model that was cranked up to the picture window framing back yards of run-down homes on a slope above Pittsburgh’s South Side.

So her husband, George, dragged the pink, little girl’s bed into a corner of the tiny living room of the one-bedroom house, even though he was exhausted himself from fighting the virus and caring for his wife and their remaining four children. He picked Chris up to move her to the other bed, injuring a knee and nearly dropping his wife in the process.

On Jan. 17, 1995, the evening she died, Chris was wrapped snugly in a favorite blue quilt, watched over by a few people who loved her. She was 42.

In the life of a family untouched by AIDS, the death of a wife and mother so young would be a devastating loss. In the Whitman family, struggling six years since the virus took hold of them, Chris’s death was just one in a series of traumatic events, yet another family mutation in response to the virus.

Their stories are windows on how AIDS is defined in the 1990s: a disease as inevitably fatal as it was a decade ago but now with a killing time stretched out by medical advances; a disease as stigmatizing as it was a decade ago but now in a much more insidious fashion; a disease that has jumped the physical boundaries of the body to take horrendous emotional tolls on the uninfected.

These new definitions are brought to life each day in the personal struggles of individuals who make up the Whitman household.

There is George, now 46, who was banished from the family by Chris in January 1989, after doctors discovered HIV as the cause of Megan’s chronic illnesses. He had unknowingly passed it on to his wife several years before after returning home from a prison sentence for a burglary connected to a drug habit. Chris in turn passed it on to the twins when they were born in 1986.

But instead of disappearing into the shadows as social workers say most fathers in his situation do, George, eventually returned to his family as Meg was beginning to lose ground and Chris was beginning to lose control. He came home to take charge, a shock to social workers involved with the family. He came home to make amends where he could and to find comfort himself. But there is no program, no counseling session yet devised to help him deal with the pain of knowing.

There is Chris, who roller-coasted from deep valleys of depression to mountain-tops of empowerment, taking her five children along for the ride. But even in her moments of greatest clarity, she could not bring herself to decide custody arrangements for the children, especially for her three uninfected sons, Ryan, 15; Corey, 14; and Matthew, 10. She did not want to face her own death in such stark terms, nor did she want to face the embarrassment of discovering that no friend or relative would be willing to take her children.

There are Corey, Matt and Ryan, middle-America AIDS orphans-in-waiting. Corey is smart enough to know what AIDS is doing to those he loves but he is emotionally unable to handle the loss. Before his sister Meg’s final hospital stay, Corey’s psychiatric bills eclipsed total medical costs for all infected family members. He has had so many school-related behavior problems and a bout with drug use. He is teetering on the edge of being judged delinquent by the court system.

Unless the course of the epidemic changes dramatically, experts predict that by the end of the 1990s, it will leave 125,000 emotionally wrecked, motherless children under the age of 18.

While the majority in that group are uninfected, there are also children like 8-year-old Melody, Chris and George’s surviving twin who is HIV-positive and symptom free. It is likely that she will outlive her father and, with her illness and age, become impossible to place in the Allegheny County social services system.

In tears after her mother’s death, she asked adults around her why the virus that killed her sister and mother has not yet taken her. “I go to my friend’s house and I’m afraid to leave because I might go home and find out that my Dad is sick,” she said after her mother’s funeral.

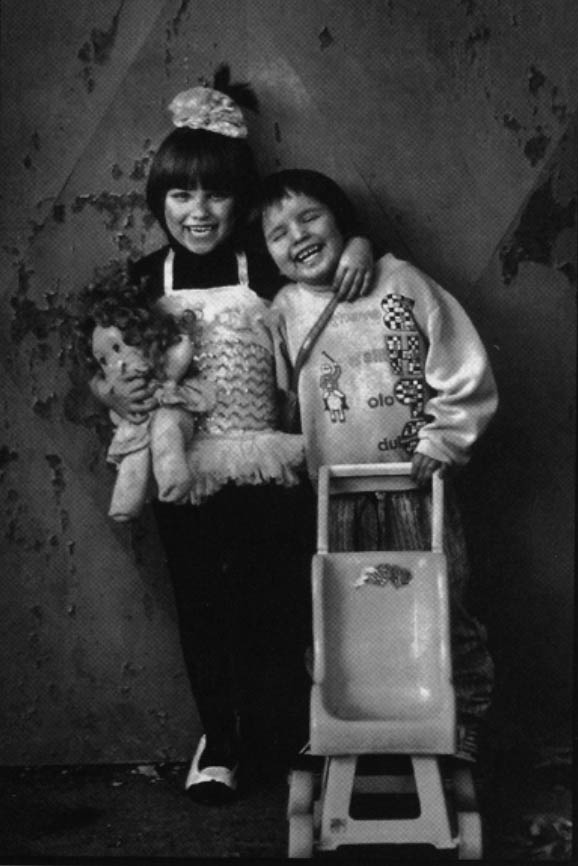

Despite these devastating individual problems, the Whitmans have survived as a family. There are stretches of time when their home is no different than those of healthy children in Pittsburgh. There are five brands of cereal in the kitchen and occasionally, spilled milk; there is bed jumping, bumps and bruises; hockey posters on the boys’ side of the bedroom, Barbie Dolls on the girls’ side; there are selfless acts and missed opportunities; ugly fighting words and lavish birthday parties; wishes fulfilled and denied and terrible dreams in the middle of the night.

There were many legacies that Chris failed to leave but this one — to keep some semblance of family life — is still in force. Chris, with her energy and street smarts, was so central to holding her family together, that with her death, social workers worry about how long the family will stay together. They admire George’s resolve but he is not as experienced with the children and his health status is a sword hanging by a thread.

If there is a single family portrait that emerges from the years spent with Chris and George and their five children, it is a snapshot of survival in the present. The nature of the AIDS virus makes the past too painful to re-visit and the future a place to be loathed. The degree of family survival has often depended on how well Chris managed each day; how well social service and health care professionals managed her.

In a Pittsburgh household running on AIDS time in the 1990s, the lives of the infected twins have come first. Every week spent without talking to a doctor is a victory; a full month without missed school is a win at the lottery; every birthday is a celebration on the order of Christmas.

It was this way for Megan and Melody, often wildly out of proportion to the lives of the three boys, who have suffered from lack of attention.

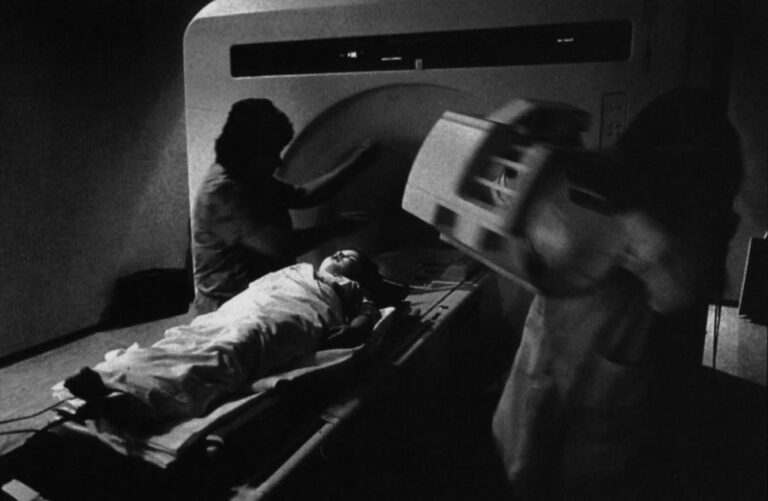

For her daughters, Chris was scrupulous about getting every bit of medical care due them. She could recite their medical histories in the clipped jargon used by clinicians, and in such detail that doctors made notes about her ability. In the early days, Chris administered most of Megan’s care at home and often called upon her oldest child, Ryan, then 11, to pin his screaming sister to the floor while she forced the bitter-tasting liquid AZT down the child’s throat.

For Megan, who averaged a week’s worth of hospital stays or out-patient procedures every six weeks of her eight years of life, Chris was especially vigilant. No needle penetrated her child’s skin, no tube was inserted, no drug administered, until she was satisfied it was needed.

The story of how the Whitman family manages to function in the grip of AIDS is the story, too, of more than a dozen health and social service professionals struggling with paltry resources to keep the family intact. “When we sit in meetings and check our progress, we argue about what has been accomplished,” says Carol Lukoff, a social worker at Pittsburgh’s Children’s Hospital. “Are these kids worse off for having been in the same house? We argue about that among ourselves. We’re operating in uncharted territory here.”

Wrestling with doubts, the social workers continue to do their jobs. On the night Chris died, Mary Anne Fisher-Cerra, a caseworker with the Pittsburgh AIDS Task Force, had to cancel a family evening out with her husband and daughter to help George round up his children and dispatch his wife’s body to the funeral home.

As funeral home attendants placed the body on a stretcher and wheeled it out the door, George picked up Chris’s battered leather purse and took it with him as if to follow her out. He was confused in his grief then, but lugging her purse for her had become a habit during the previous six months when Chris ventured out for a doctor’s visit or a hospital procedure. Like so many young mothers, she was lost without that large handbag.

Later that night, when tears were beginning to well-up in George’s eyes and he was searching for a constructive task, he dumped the purse’s contents on the empty pink bed trying to find the book of important phone numbers. It was time to start spreading the news.

The image of that deflated purse lying useless at the end of the bed, brought home the finality of Chris’s death. Some of its contents represented dreams unfulfilled and goals unmet. A few items were trophies from small victories in a larger war she could not win.

I remember joking about the size of that handbag – saying it looked like a baby sitting in her lap — in that first meeting with Chris, a sweltering June day in 1991. She was burrowing into it in search of a loose cigarette and I was searching for something to cut the tension in the tiny office of her caseworker from the city’s AIDS Task Force, one of the few places she felt safe in those early days. She was supposed to decide whether to let a writer and photographer do a story on her life and the lives of her children.

Over the next few months, as she grew to trust us, I began to keep a list of the handbag’s contents, a telling mix of the ordinary and extraordinary:

the latest school photograph of each child, a prayer card from her mother’s funeral; a half-used book of food stamps and crayoned drawings made by her daughters; phone numbers of social workers and doctors accessible in a crisis; phone numbers of bar friends to help her escape. There were travel brochures for a fantasy beach vacation and a pack of unpaid utility bills; AIDS drugs for her and for Megan, and a five-year date planner book.

It wasn’t until her death that I realized what Chris had been toting around wasn’t really a handbag. This daughter of Pittsburgh’s rough-and-tumble North Side was carrying a hope chest on an arm strap. Only now, does it seem so extraordinary that this welfare mother, this head of an AIDS-shattered family, would dare to hope — indeed to expect her family to stay together under one roof.

For a family living on AIDS time, even the few drugs to offer hope were regularly cursed. Not only were small children repulsed by the taste of AZT, the drug has serious toxic side-effects including corrosion of baby teeth, forcing some children to undergo painful extraction procedures.

Chris lasted only 15 minutes into Meg’s first tooth-pulling procedure. “Between all the blood and her screaming, it was just too much. It had to be done but I couldn’t take it.” she said afterward. It was the only time I ever saw her leave Megan’s side in a medical setting.

Her first-hand knowledge of all the pain Megan endured and the limitations placed on the child’s life because of AIDS fueled an activist temper.

In the twins’ names, Chris forced school administrators to adjust written AIDS policies to real life; relentlessly pursued charities to win clothes and furniture and appliances; snatched up trips to Disney World, to the eastern shore, to an AIDS summer camp in the Sierra Nevada mountains of Northern California. She also became a street-level spokeswoman for mothers of children with AIDS, warning them to “fight like hell now for what you can get because there is no later on. You’ve got to be a pain in the ass to get what you want for yourself and your kids.”

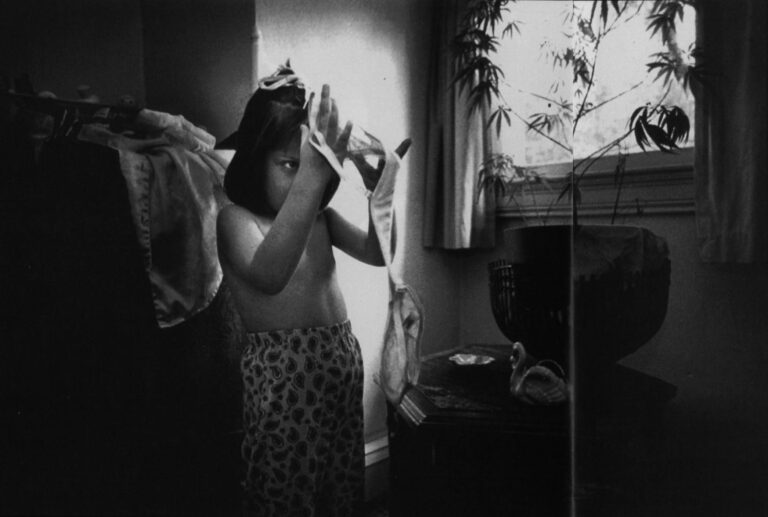

In a household running on AIDS time, the plea of then 6-year-old Melody to wear a bra “just like mommy” was enthusiastically embraced by Chris. She took her daughter to a department store to indulge in this mother-daughter ritual, ignoring the stares of other shoppers and the disapproving looks of clerks.

At lunch in a neighborhood restaurant a few days after that purchase, Chris broke into tears trying to explain it all.

“If I could figure out a way to send my girls down the aisle in wedding dresses I would do it,” she said wiping her nose with a napkin. “People who don’t have to live with this don’t understand. There is this pressure to cram everything in that you can. You want their lives to be as complete as possible.”

“Isn’t some of the cramming for your benefit, too?” I asked.

“Well, sure. So what?” If people want to criticize, she said, “let them spend a week in the hospital watching a kid with AIDS.”

It is this inability to translate the mother-AIDS-child experience to outsiders that draws so many HIV-positive women and their children into deep, almost familial bonds. Children’s Hospital social worker Lukoff noticed Chris’s social nature and her activist spark early on and recruited her to meet with young mothers reeling from an HIV diagnosis.

One of those was Sherry Hopkins, a 29-year-old mother of a one-year-old boy who had returned from Atlanta to her parents’ Pittsburgh after being told of the infection. A week before Christmas 1990, Sherry met Chris in a corner of a large conference room at Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh. On the surface the two were mismatched. Sherry’s roots were in rural southwestern Pennsylvania. She was a black woman, tall — over 6 feet — and thin. She had a quiet demeanor and a soft sense of humor. Chris’s roots were urban Pittsburgh. She was white, of medium height and stocky. Lukoff introduced them and left the room.

It was an awkward first few minutes until Chris pulled her children’s pictures out of the ever-present handbag, spread them out on the table and began running through their biographies. Sherry responded with a picture of her son, Jesse.

A friendship sparked by the common bond of children deepened during the next two years as the women compared notes about their children’s ailments and shared their own heartaches. Sherry was grateful to have her parents’ help but she needed someone who wasn’t afraid to talk about living with AIDS. She needed Chris to help her confront hard truths and teach her survival skills.

Chris desperately wanted a companion who spoke the language of AIDS: someone who knew what a CD-4 cell count was, who knew which hospital workers to avoid and which to seek out. She wanted to be able to connect with someone separated from her husband because of the AIDS virus, someone who spent too many days sitting with a sick child and too many nights retreating to bed alone.

As Jesse’s health declined, Chris was a steady source of support. She and the children would often visit in the hospital or babysit at home, allowing Sherry time to herself.

In one hospitalization the winter before Jesse died, Sherry told Chris that her son had never played in snow. Chris, with all five children in tow, filled hospital wastebaskets with snow and carried them to the room. They lined Jesse’s hospital bed with plastic garbage bags, dressed the boy in a snowsuit and plopped him into the melting mound where he squealed with delight.

Standing vigil with Sherry throughout her son’s decline, propping her friend up at the funeral when the boy died in March 1992, just a month away from turning 4, Chris thought she was banking strength — an emotional insurance policy for her own inevitable loss of Megan.

Two years after Jesse died, Sherry died and Chris realized after that funeral that there wasn’t any insurance to ward off the pain. Too many people dear to her had died; too many more were dying. “They’re all leaving us, Meggie,” she whispered, while hugging her daughter on the couch the night after Sherry’s funeral. “I know this,” she told me while staring at the TV after her children had gone to bed. “I’m not as strong as Sherry. I don’t want to go on without my Meg.”

@1995 Douglas Root and Randy Olson

Douglas Root is a freelance writer in Pittsburgh. Randy Olson is a freelance photographer in Pittsburgh. They are Josephine Patterson Albright fellows of the foundation.