Here is the dream that kept coming back to Corey Whitman in the fall of 1991, a few weeks after he turned eleven:

He and his parents and his four brothers and sisters are camping out in the woods in a motorhome, a spanking new vehicle with a powerful engine, a kitchen area, TV, stereo and bunk beds with spreads in the colors of his favorite pro football team, the Pittsburgh Steelers. But Corey doesn’t want to sleep in the trailer, he wants to be out under the stars.

That is where the dream continues – at night, under the stars. Corey is lying on his sleeping bag at the edge of a campfire where the entire family – his Dad, George Whitman; his Mom, Christine Skubis; siblings, Ryan, now 16; Matthew, 11; and twins, Megan and Melody, 8 – has gathered around to sing songs. He dozes off to sleep to the sounds of their singing and is jolted awake to the sounds of the motorhome’s engine.

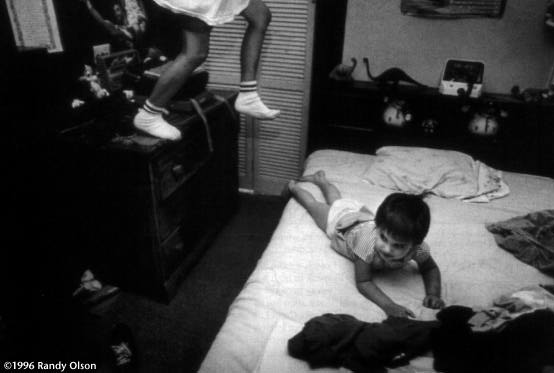

At age 11, Corey attempts to fill an adult role and helps his mother care for Megan.

He can make out the faces of his twin sisters and his parents in the motorhome’s windows. They are waving as the vehicle pulls away from the campsite. His two brothers have disappeared. The stars are gone and the campfire is dying. He is alone in the woods.

Corey did not understand what the dream was about back then but it bothered him enough that he told his mother. It bothered her to the point of tears as she re-told it to me. She realized that he had figured out on his own what she could not bring herself to tell him for two years – that she and his father and two of his four siblings were infected with the AIDS virus.

He wasn’t versed in the details but he was quick enough to put together the clues. Chris was continuously involved in working with one AIDS group or another, even being flown to other cities for entire weekends as a leader in a parents AIDS advocacy organization.

He saw too much fretting over his sisters, the fraternal twins, each time they were sick; too many social workers knocking on the door; too much family socializing with people who had some connection to AIDS; too much reverence given to the wicker basket on top of the refrigerator stuffed with prescription drugs.

Corey suspected everything and was told nothing.

He knew better than to ask, so he confronted the truth in his dream. It was a frightening combination of fantasy and nightmare – a family camping trip as a luxuriously normal vacation for a teenage boy in an abnormal household. Thrown into this dream was a child’s paralyzing fear of abandonment.

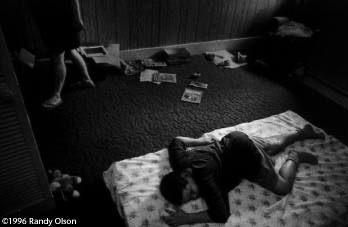

Now nearly 15, he says he does not remember the dream but he does remember the effects of it: waking up in the dead of night yelling for his mother, clutching the sweat-drenched sheets of his bed and refusing to let go; doing this so frequently that his siblings put pillows over their ears to block him out.

There is no good reason why he should remember, as so many more cataclysmic events have occurred in the years since that his dream is now just a footnote. It became a harbinger of real life rather than a subconscious release from it.

Corey Whitman is a 1990s child of the AIDS pandemic. His connection to the virus comes not from physical infection but emotional connection through family blood. The hundreds of pages of medical charts, psychological assessments, school reports and social service notes filed under his name dwarf the case histories of many people in Pittsburgh with full-blown AIDS.

In the span of four years, as his school friends moved into adolescence fretting over making sports teams and attending first dances, Corey was enduring traumas that would bring most adults to their knees.

For more than a year, Corey secretly believed he was the cause of his younger sister Megan’s chronic illnesses when he passed along a case of chicken pox. In March 1991, the virus put her in the hospital for a week and nearly caused her death. It wasn’t until Corey was put under psychiatric treatment in the spring of 1992, after several violent attacks against his siblings in the home, that doctors implored his mother to tell Corey the truth – that Megan’s illness was caused by AIDS.

There have been three psychiatric commitments for Corey, including a five-month stay at a state hospital. His behavior problems caused transfers through four schools in Pittsburgh’s public system. At state expense, he is now attending a private school for children with emotional problems.

Last summer, as he rebelled against outpatient sessions with psychologists, he endured Meg’s death. During the next six months, he was a silent observer of his mother’s steady decline and death. Her last weeks were spent on a daybed in the living room of their tiny rented home on the city’s South Side. While his brothers and sister regularly have attended sessions with a bereavement therapist supplied through efforts of a group of social workers, Corey stubbornly has refused to see her.

He still has his father, who remains relatively healthy and is now the family’s primary caretaker, but the two have a strained relationship. The pain of losing two family members to AIDS is still fresh and Corey, like many children destined to survive their AIDS-infected parents, he has been reluctant to forge emotional attachments with yet another he is likely to lose.

Corey Whitman is among the first generation of Americans who will likely grow into adulthood as an AIDS orphan. What there is available on the statistical map provided by the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention suggests that he is in the older ranks of a group expected to swell to 125,000 by the end of the decade.

A recent Journal of the American Medical Association study offers an estimate of 80,000 and backs up other studies that show the majority of these children are well under the age of 15, raised by single mothers and in need of so many services that a few dozen cases alone can overwhelm social service agencies.

In all, more than a dozen health and social service professionals in Pittsburgh meet monthly to try to assess the Whitman family’s needs. The group’s goal has been to keep the family functional and under one roof, to keep the children in school, to keep Corey and his brother Ryan out of juvenile hall. At least three professionals in that group are focused primarily on Corey, It is a daunting task for each.

At the mid-point of this decade, the number of women diagnosed with AIDS is growing by about 18 percent a year, compared with 3 percent for the general population. Yet there are few programs available, especially in mid-sized American cities like Pittsburgh, that target this growing group.

Social service and health professionals have little research to guide them and few funds available to deal effectively with AIDS-infected women and their AIDS-affected children.

“How do I reach a mom like Chris, who is willing to speak to high school students about every personal detail of her family’s AIDS situation but she can’t tell her own son?” asks Carol Lukoff, a Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh social worker, echoing the frustrations of colleagues from San Francisco to Kansas City to New York City.

Lukoff, who has been working with the Whitman family for four years and handles about 40 other AIDS-affected families, says social workers also are searching desperately for more effective ways to assist fathers who take over from the mother but lack home management and child-rearing skills. In the case of George, he has been successful managing the house, less so at managing the household.

It is a sweltering afternoon in early June, a few days after the end of Corey’s school year. He is slouched against a railing in front of the house. The bangs of his brownish-blond hair fall over deep, blue eyes. He jerks his head back frequently, throwing the hair back over his head. He is waiting for a visit from the police.

Corey is grinning slightly at Mario, his best friend in the neighborhood, who is sitting across the street at the edge of a neighbor’s front yard. He is able to make eye contact with Corey but he is a comfortable distance away from the lecture being leveled by George, who is standing on the front porch.

George is a tall man, about six feet, and very thin. He wears a baseball cap on top of thinning gray hair and he is rubbing his short salt-and-pepper beard with one hand, waving a hand at Corey with the other.

“All you had to do was call the house and tell me you were staying over at this boy’s house,” he says, pointing to Mario. “But you didn’t want to be bothered, did you? And so we spend half the night looking for you and I have to call the police and tell them you’re missing. And now you can just wait all afternoon for all I care until they get here to talk to you.”

“Ain’t waiting no all afternoon,” Corey mumbles while looking at the ground. “I’ll leave first.”

“Ya, you just go ahead and do that and you know what they gonna do? They are just gonna bring you into that juvenile court, the one you like so much, and they’ll bring you before Jaffe and he’s gonna be real pleased with you. He’ll just lock you up.”

“No they won’t. I’ll just run away. Hey. I called, OK? No one was home and I don’t like to leave messages. I don’t like answering machines.”

George turns away and laughs. There is silence for a minute or so as the waiting continues. Then George begins to pester Corey about taking his daily dose of a drug prescribed by psychiatrists to flatten out his mood swings. Corey finally relents and goes inside.

Later, George tells me he trusts the officers who are supposed to pay Corey a visit. They had been very cooperative when George found out that Corey was smoking marijuana. Earlier in the summer, he had gone charging up the steep hill in Arlington to the local convenience store where Corey said the drug had been sold and found the same neighborhood officers in the parking lot.

“I told them I’ll make you guys a deal. I’ll give you a chance to bust those guys selling the stuff to my son and then I go up with a baseball bat.’ They said they would be the same way if it was their kids.”

The day after the incident, George rode the bus with Corey to school and signed forms to have him tested for drugs.

Unlike his brother, Ryan, who as the oldest was the surrogate father and blames George for his lost childhood, Corey desperately wants a father-son relationship. But the years of separation and the resonance of his mother’s anger have put up some high walls.

Its beginnings go back to when Corey was 5 and his father was banished from the house by Chris after a prison term for a burglary related to drug use. He has had to work through his mother’s vilification of George as the cause of the AIDS infection in the family and the cause of their slipping from a blue-collar lifestyle to a welfare existence.

But as Chris’s health declined and her coping abilities diminished, George returned to the home, gradually taking over the role of primary parent. Chris needed his help but she did not make it easy, often berating him in front of the children, telling them they need not obey him, and reminding them that she considered their marriage finished.

George would defend himself only occasionally. Most often, he would leave the house and go for a long walk, eventually returning to finish the household chores – washing, cleaning, cooking. He fed and bathed Chris, supervised his children’s homework, attended their parent-teacher conferences, organized the household finances and worked odd jobs on the side. Corey, always the careful observer, was confused about the two disparate pictures of his father.

George’s attempts to place limits on his son’s freedom have caused explosive confrontations between them – bursts of temper, swearing, even physical threats. On other occasions, Corey has surprised George by washing a load of clothes, mowing the patch of yard or preparing school lunches for his younger sister and brother.

“Now Dad, you’ve got to just eat all of this, eat it all and make sure you eat every day. Just, you know, take care of yourself so you don’t get sick,” he told his father recently after making him a sandwich. Corey is old enough to know the personal consequences to him if his father becomes seriously ill, but he is young enough to indulge in the belief he can stave it off indefinitely.

When George can no longer hold his own, the children will likely be split up and moved into group homes or, if they’re lucky, farmed out to relatives in eastern Pennsylvania.

In a society where adolescence is usually a process of limited exposure to adult independence, always with secure grounding in family and daily routines, Corey’s has been thrown into reverse by the virus.

His teenage years thus far have been marked by intermittent exposure to the security of family and the continuity of routine. His only certainty about the future is that he must rely on himself.

“You look at this kid and you wonder: what is the first thing he thinks about when he wakes up in the morning? There is such a long list of worries that have no business being in the head of a 12-year-old,” said psychiatrist Dr. Humberto Quintana, shortly after Corey’s release from Mayview State Hospital. “And how much thinking does he do about the future? Probably as little as possible.”

Chris never really came to terms with the reasons for Corey’s psychological problems. She insisted her son was suffering from Tourette’s Syndrome and that given enough treatment and the proper medications “everything would be back to normal.”

Her sideline diagnosis was an exercise in denial. Chris refused to accept the possibility that her son could be so affected by AIDS when he didn’t have the virus himself.

“I think Mom had the idea that you put a kid in the hospital for enough treatment and honesty doesn’t matter,” said Quintana. “We patch him up and he goes home and that’s it. She came to understand otherwise. What we need is some real punch to get into the homes where all this craziness is going on and stabilize things before a kid like Corey ends up in a state hospital.”

©1996 Douglas Root and Randy Olson

Douglas Root is a freelance writer and Randy Olson is a freelance photographer, both based in Pittsburgh. They have been examining the impact of AIDS on a Pittsburgh family for the last several years.