Photos by Marc Geller

NEW YORK-The walls of the elevator were polished mahogany. Inside stood four people. A somewhat severe elderly woman in a business suit was coming home at day’s end. An unmistakably wealthy gentleman with a maroon silk ascot and yellowish white hair made chit-chat with his companion, a young, very athletic Puerto-Rican man whose thighs pressed tight into his jeans and whose dress shirt opened deep into hairy cleavage. The young man in turn was visually grazing over and allowing his hips to drift against the body of the fourth person, a thin, middle-aged man who seemed to relish the spontaneous tableau of flirtation which remained invisible to the tired businesswoman.

The three men stepped out onto the fifth floor of this upper Fifth Avenue apartment building. A varied assortment of model-pretty young men took jackets, poured champagne, and directed the guests to silver and crystal bowls of caviar, cornichons and exotic canapes.

“So nice to see you again,” the host, an auction house executive greeted his guests, handing them a card and a pre-addressed envelope. “There will not be a pitch tonight, but don’t leave without filling out the card and writing a check,” he said with grace and a smile.

The gathering was not a fundraiser as such. It was one of the host’s regular, quarterly “gentleman’s gatherings,” where men of a certain age and status enjoyed the polite company of a couple dozen young men and each other. But in autumn 1990 even the most elegant gay men at the toniest parties were not separating themselves from their sense of political obligation: the defeat of North Carolina’s arch conservative senator Jesse Helms.

At gay bars and parties and bookstores and beach houses from Portland, Maine. to West Hollywood, California, gays and lesbians organized what is almost certainly the biggest electoral fundraising effort in the history of the modern gay movement. They poured an estimated $I million into Harvey Gantt’s campaign to displace Jesse Helms from the Senate.

Based on North Carolina’s previous senatorial campaigns, Harvey Gantt accumulated all the votes he should have needed to win-thanks in considerable part to the help he got from gay Americans. But that same gay help may also have cost him the election. The result has brought some campaign strategists to rethink the role of the apparently growing gay vote.

“People think it was the racism that was so devastating [to the Gantt campaign],” says Mandy Gruenwald, Gantt’s chief media strategist, “but the single toughest thing was a TV spot that accused Gantt of supporting mandatory gay teachers for our schools.” In that spot the Helms campaign equated Gantt’s support for gay anti-discrimination protection with requiring that public school teachers be homosexual.

“It was the turning point in the campaign when they put that spot on the air,” Gruenwald said. “We had been ahead until then by 4 to 8 points and then we were 6 points behind within breathtakingly little time. There was no other major factor that had been tossed into the dialogue.”

By pressing homophobic fear of gays, Gruenwald says, Helms was able to bring out voters who had never participated in an election. Gantt actually won 150 thousand more votes than North Carolina’s other senator, Terry Sanford, did in 1986 when 1.6 million North Carolinians voted. But in 1990, Gruenwald points out, 2 million voters went to the polls, “so it was enough of a gut hate in people, fear, that it could change the turnout in an election.”

Gay electoral strategists acknowledge that in conservative southern states, rightist reactions can sabotage gay electoral gains, but overall they say that gays are making major inroads into the calculus of campaign politics.

Of all the subgroups in the American electorate, gays are probably the most complex and difficult to assess. The old Kinsey studies suggest that about 10 percent of the population is gay, thereby suggesting that there are some 12 million voters. Yet a majority do not openly identify themselves as gay and are therefore hard to reach. At the same time, many of those 12 million identify themselves in other constituencies-black, Latino, Asian, or feminist. In short, it’s very hard to know exactly who, what and where the “gay electorate” is.

Despite all these complicating factors, self-identified gay voters and their political organizations seem to be growing steadily. Sean Strub, who advises candidates and also runs a national direct mail marketing firm directed at gay households, says that gay money and gay voters have become more and more important to centrist and liberal candidates.

“Straight politicians are now overtly courting the gay vote,” he says, and it’s not hard to figure out why. However difficult they are to define, there are about as many gay and lesbian voters as there are blacks and Latinos, and there are three times as many gays as Jewish voters. And gay middle-class men, lacking children and education expenses, may actually have more disposable income to spend on candidates than any other group of Americans. As a result, ever-hungrier politicians are beginning to realize that gays offer unacknowledged and untapped reserves of cash and votes.

The 1989 Atlanta mayoralty race offered a case in point. Though few people think automatically of this huge and increasingly sophisticated southern city as a “gay mecca,” there are an estimated 300,000 gay-identified people in the area-most of them white.That’s enough voters that neither of the two leading Democratic candidates dared ignore them. Both former mayor Maynard Jackson and then County Commission Chairman Michael Lomax offered clear platforms on gay issues, addressing issues of anti-gay violence, appointment of gays to public posts and provision of support to people with AIDS.

What gays offered in Atlanta-a predominantly black city-is the same thing they have offered to black candidates in Washington, D.C., namely, a large block of relatively affluent, white voters who would respond to issues of discrimination and social exclusion. “By appealing to the margins,” says Georgia State University political scientist Les Hough, “to the single issue groups, you can solidify your white support-and in a close race, it can make a difference.”

At a statewide level, however, the reverse may be true, and in a conservative state like Georgia, Hough says, candidates would almost certainly “downplay gay rights issues.”

While almost everyone agrees that the last two decades of open gay activism have turned gays into ever more important players, that success has produced a tricky and often very difficult balance between single-issue politics and constituency politics which almost no other group faces. Like the women’s movement, which has pushed hard for abortion rights and professional and pay equity, gays have been identified with key target issues–AIDS, personal safety, non-discrimination. But at no more than 10 percent of the population (of whom at most half are publicly active), their numbers are too marginal to force gay issues into major political campaigns. At the same time, while absolute numbers of gays equal or exceed the black, Latino or Asian population, gays have neither the history or the geographical concentration to guarantee electoral representation.

Even in San Francisco or West Hollywood, possibly the nation’s two most heavily concentrated gay cities, gays and lesbians equal less than a quarter of the population. And further, gay members of other ethnic and racial blocks very often look with suspicion on established gay groups as white, middle-class forces which offer them less support than their own natural communities.

The question of identity is critical to any level of political participation, whether it is with an issue, a party or a sense of ethnic heritage. The steady decline of American participation in formal politics seems almost certainly linked to increasing levels of division and confusion over the ability of parties to offer coherent visions in a time of divided identities. The challenge facing gay political organizers may be only a microcosm of the broader conundrum in American political life.

“Yes, there is the makings of a gay voting block,” argues Eric Rosenthal of the Washington-based Human Rights Campaign Fund, a gay political action committee, “but it can’t be quantified and proven. It’s not as strong as the black or Jewish or women’s voting blocks, and the reason is that people don’t become gay until 15 to 30 years after you’re born into other voting blocks. If you’re born black or Jewish, you get certain values of other black or Jewish people handed down to you from infancy on. But gay people don’t come to understand their identity until adolescence or adulthood. and so that sense of being a part of a group or a block takes longer to develop.”

If gays have already formed a political identity within the families and communities of their birth, then they must be lured away into new and much riskier political work. If, as seems increasingly the case, they have simply never developed strong political allegiance, they are even harder to reach when the demands, of mateship and career are high.

Rosenthal tells a story about a gay man he came to know at the Capitol Hill Squash and Nautilus Club who was working for the Republican National Campaign Committee.

“I asked him how he dealt with issues like [the effort to recognize gay couples as] Domestic Partners. ‘Domestic issues aren’t that important to me,’ he said.”

“Think of what he was saying, that the most intimate issues of his life, the recognition of his rights in the household with his mate, weren’t important to him. People are capable of separating parts of their lives from each other.”

Frequently, Rosenthal says, gays who work in state and national politics are still so fearful that they actively avoid focusing their energies on gay concerns. “I had a meeting with the legislative director for a southern congressman. This guy’s as queer as the day is long. When we sat down and started to talk, he positioned himself on the couch as far away from me as possible–and this is a guy who works for a congressman who’s supportive of gay issues. He did not want to be dealing with THAT issue-gay issues. It was just a general meeting in which I was laying out our program at HRCF. This guy could barely utter a word.”

Despite all these obstacles, gay issues have gained ground steadily with voters and legislators over the last decade. Anti-discrimination laws have been passed in four states and in more than a hundred counties, towns and cities, including Washington, Los Angeles, Chicago and New York. Most of those laws have been passed by straight politicians sympathetic to gay causes, but pressure has been mounting to win direct representation of gays by gay politicians.

Strub, the gay marketing expert and campaign consultant, decided to test the waters himself in 1990 in a contest for New York’s 22nd Congressional District in upstate New York. Strub claims being gay was an asset, that his knowledge and experience as a gay man won him respect and support from straight voters.

“When I talked to seniors, I said let me talk to you about national health care. When I talked to women and native Americans about stereotypes, they knew that I know what I’m talking about. The fact that I’m gay qualifies me for office as an expert on these issues. It gave me credibility.”

Strub lost the Democratic primary, but he believes that the 45 percent of the vote he won on his first time out as an openly gay man demonstrates the growing viability of gays’ place in electoral politics.

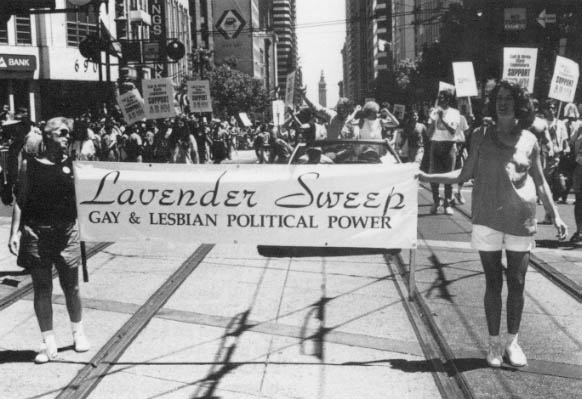

There are a handful of openly gay state legislators in Maine, Connecticut, Oregon, Washington, Texas, and Minnesota, but none of them are seen to have secure “gay” seats as do blacks in Detroit or Newark or Hispanics in Miami and San Antonio. This year in California gay electoral activists have mounted an unprecedented campaign to carve out actual gay state assembly districts within this year’s reapportionment negotiations. “The purpose of the project is to target those areas where we think we can have a viable gay or lesbian candidate,” explains John Duran, co-chair of WESPAC, a California gay political action committee.

The problem WESPAC faced is the inability of the Census–whose data determines electoral districts–to identify gay and lesbian voters. So it collected mailing lists from dozens of gay groups, from marketing companies. to older gay PACs to gay magazine subscribers to identify just over 200 thousand gay and lesbian households. It is the first time any such roster has been made, though the agreements made for its compilation excluded using individual names or making future mailings to the addresses.

“We know not only which areas of the cities are gay, but in which precincts gays live, and we cross-checked that data with [recent AIDS-related] initiatives showing how people voted,” Duran says.

What WESPAC also found was that those highly concentrated gay sections of San Diego, West Los Angeles, Long Beach and San Francisco were all broken up, divided into different state assembly districts. Their object now is to have actual gay districts redrawn in the reapportionment process so that gays can choose their own representatives.

“In 1980 (at the last reapportionment) most of us were still dancing in the discos,” said Duran. “We didn’t have a statewide effort. We’re only 11 years out of

Stonewall. The movement was quite young. I think we’re quite sophisticated now.

“We’re going to take our maps in, present our data and say this is where our people are. The next step is to say this is how we think our map should be kept together.”

The problem, political insiders say, is that gays, as the newcomers in the electoral system, are an unproven constituency. In West Los Angeles three liberal Democrats are already having to scramble to preserve their seats due to population shifts. Los Angeles’ other large gay enclave, Silverlake, is already divided among three Assembly districts with major claims from Asian and Latino interests. And in San Francisco, a preliminary outline of a gay Assembly district could divide current black and Latino constituencies.

Brandy Moore, a gay black activist with long experience in San Francisco politics, says that the Democratic state leadership is unlikely to tamper with existing district lines in any way that could jeopardize current assembly seats. ‘They’re not going to split the coalition they already have in order to accommodate us. Why create a new district when you know you already have a solidified district you can count on?”

The question emerged earlier this year when gay activist Cleve Jones announced he would challenge Assemblyman John Burton. Burton, a liberal whose elder brother, the late Philip Burton built the state’s most powerful Democratic apparatus in modern times, is the chief sponsor of Assembly Bill 101, the California Lesbian and Gay Rights Bill, a jobs and housing anti-discrimination act. Jones both worked in the statehouse and won national recognition as founder of the Names Project which sent the AIDS Quilt to cities across the country.

For Jones. as for WESPAC’s John Duran, the time has come for gays and lesbians to quit relying on straight liberal politicians to press the gay agenda. “When I unfolded the quilt in Washington,” he told a local reporter, “I believed in my heart that legislators would understand the epidemic and that they would be moved into action. But after four years of demonstrations, prayers, and voter registration, none of this has moved government. I want to bring that frustration and urgency to Sacramento and I believe I can do that in a unique way.”

Moore, a former aide to state Assembly Speaker Willie Brown, the most powerful politician in the state after the governor, says he warned Jones that state party leadership would oppose him.

“I told him sure you should run. Somebody’s got to run to begin the dialogue, but you’re going to get your butt kicked. He went to the Speaker, and the Speaker said, ‘You’re crazy. You’re not going to win in this city.’”

“But Cleve believes that there are enough gay votes to offer a challenge to the Democratic party.”

Moore argues that before gays make a mistake by pressing for gay districts where gay candidates are guaranteed to win only on gay identity issues. That, he says, is “single issue politics.” Even in heavily gay cities like San Francisco and West Hollywood he believes must work through minority coalitions. “The question is, do you have real commitment to human beings and to basic services like housing and education? We haven’t been able to prove that to the Democratic party. It will come–probably not through Cleve and WESPAC–but as soon as lesbians and gay people learn to build coalitions.”

WESPAC co-chair John Duran acknowledges that gay-responsive redistricting is an uphill battle, but he believes the effort will have proven valuable in any case. “I don’t know how serious they’re taking any of us. We think it’s worth doing, because if we don’t do it now, we’ll have to wait until the year 2000.”

At a minimum these new gay electoral initiatives amount to basic institution building which in and of itself may give gays and lesbians a stronger hand in any broader coalition they might join. Without the ability to identify and target its own people, it is unlikely to raise money efficiently, recruit precinct workers or produce votes–all functions which future coalition partners are sure to demand.

The lack of such basic political institutions has twice proved embarrassing to gays recently, first concerning federal rules which exclude AIDS-infected travelers from entering the United States, and second over support for the California gay rights bill.

Gay and AIDS activists believed they had finally succeeded in eliminating the HIV travel exclusions–as public health officials have long urged–when the Bush Administration announced proposed regulations dropping the exclusion. Then just before the changes were to be formally announced in June, the Administration announced a two-month delay. In the meantime, religious fundamentalists and supporters of Sen. Jesse Helms, who had introduced the exclusions several years ago, flooded the Administration with mail.

“We dropped the ball,” admits Fred Hertz, an experienced gay and AIDS attorney in San Francisco. ‘The right wing sent in 40 thousand letters and we didn’t send in any. Nobody had their finger to the wind. Somebody should have known that the Administration was getting 40 thousand letters and gotten off their duff.”

Hertz contrasts the gay response with standard Jewish political action. When then-White House chief of Staff John Sununu seemed to suggest in June that some of the embarrassment he suffered his personal travel resulted from enemies in the Jewish community, he found himself in a conference call with eight national Jewish leaders the next day. At a pivotal point in the 1980s campaigns for the release of Soviet Jews, Hertz notes, the word went out to produce mail.

“Within a week or two there were campaigns in every Jewish social organization, synagogue, educational institution. There were letter campaigns, poster campaigns, sermons at synagogues.

“In the gay community local organizations don’t belong to any national network,” Hertz said. “There is no national association of gay Democratic clubs so that notices could be sent to all the clubs nationwide. Secondly, most gay people don’t belong to any organization, so that even if a network developed, it would not reach those people.”

Just as embarrassing was the lack of grassroots support for California’s gay rights bill while it was moving through critical legislative committees. Then during the spring a one-page flier began to circulate around Southern California. Its three-word headline read: “Wake Up, Faggots!”

What followed was an impassioned, if not exasperated call to action for gay and lesbian support of the bill. Calls and letters were running 100 to one against the legislation from fundamentalist conservatives even though Republican Governor Pete Wilson had already indicated he would sign it.

“Whether we were busy feeding homeless people with AIDS or watching reruns of ‘Three’s Company,’ the message we are sending to Sacramento is that the gay community does not care, that the gay community cannot be bothered to support its most critical legislation,” the bill’s backers said.

Eventually, gay activists generated a statewide letter-writing campaign which matched the anti-gay conservatives, but the lethargic gay response–on an issue of direct interest to gays–raised sharp questions about whether gays can yet organize themselves as a significant force in American electoral politics.

©1992 Frank Browning

Frank Browning, a freelance writer in San Francisco, is examining gay culture in America.