Photos by Marc Geller

The first time I saw Jim Corti was in Miami, on a hot, sticky night in May 1989. We were both seated in the restaurant at the Howard Johnson’s motel on the north edge of the city, a rather sad establishment that had seen too many humid, tropical summers since the last paint job. We were at separate tables, eyeing each other from time to time. I was alone. Corti sat with three other men. We had not yet been introduced and were not sure how to recognize each other.

I had come to witness and record an underground treatment of four HIV-positive gay men, two with AIDS, who had volunteered to be injected with a promising but possibly deadly Chinese drug. Corti, I had been told, was a famous, or at least notorious, crusader. A doctor, one person told me. A nurse, said another. In fact, by his own account, a nurse and a smuggler.

Corti and a small alliance of gay men have been pressing the limits of the federal Food and Drug Administration’s tolerance since 1985 when they began importing unauthorized drugs for friends and acquaintances dying of AIDS. They have gone to Mexico City and Tijuana to obtain a drug called ribavirin, wearing color-coded pins on their collars to identify each other and their Mexican pharmaceutical contacts. They have negotiated discount deals for dextran sulfate from Japan. And they have organized networks of secret laboratories where they analyze and refabricate experimental drugs unavailable through legal pharmaceutical outlets.

Altogether these AIDS activists are key players in a larger and even more unlikely movement through which gays who until very recently were integrally defined as “diseased people”-have challenged some of the most fundamental tenets of the American health care system. Stigmatized at the beginning of the epidemic by local and federal agencies who were embarrassed or uninterested in the disease, they launched unprecedented self-education and prevention campaigns, challenged complicated protocols of academic research, and invented caregiving models which both reduced healthcare costs and permitted the sick to remain within their own homes and neighborhoods. Along the way they found their own values, behaviors and relationships transformed.

Few activist operations spread as much excitement as the underground testing of Compound Q. Derived from the root of a stubby Chinese cucumber, the first reports about it sent shock waves of anxious anticipation through AIDS-decimated gay ghettos of New York, Los Angeles and San Francisco. People were so desperate and the disease so overwhelming that even the most sober-minded and intellectually skeptical men were ready to anoint it as an almost mystical elixir from the East–from China–which would save all their gay brothers whom Western science had failed. One friend, head of a nationally prominent AIDS service organization, had needed to believe in the cure so much that he told me AIDS would be a dead issue within a year. That was April 1989. On his tip I made the contacts that would lead to the shabby Howard Johnson’s which, for one weekend, would be a makeshift AIDS clinic under the direction of nurse Corti.

This HoJo’s is stashed between a freeway interchange and a putt-putt miniature golf course. Outside, sleepy-eyed Cuban security guards lounge on bent folding chairs, tossing cigarette butts under the bougainvillea. The elevator reeks of too much spilt beer. Tropical mold seems everywhere on the march.

Three rooms are reserved and registered to one man with a phony name who has directed no maid service for the entire weekend. In many cities such requests might alarm the management. In Miami, gateway to the global cocaine market and staging ground for most of the covert operations against Central America over the last quarter century, hotelieres take off-standard bookings and requests in their stride. Miami is still America’s Casablanca.

I call the name I’ve been given at 8 p.m. and am invited upstairs where I meet a young, doe-eyed man named Paul Ellis, Corti’s co-conspirator who sometimes prefers the name Paul Sergios. Both men have worked the AIDS drug underground for several years. Their room is clammy cold and stays that way thanks to an old fashioned air conditioner inserted in the wall. Ellis is laying out an array of syringes, swabs, thermometers and IV bottles obtained through a friendly local doctor.

“This is totally illegal, essentially holding an experiment, which is not FDA-approved,” he advises. There is eager petulence in his voice. He is thriving on the film noir ambience of the operation. He also makes regular complaints about how horny he has grown since his return to Miami from Los Angeles, a complaint he emphasizes by regularly groping beneath the elastic band of his red short-shorts. Several times over the next two days he emphasizes that he is a medical revolutionary, a man who has undertaken great risks not only to save lives but to remake the way this nation does medicine. “This is part of a revolution against the FDA, and I’m happy to be a part of that,” he proclaims. Yet if Ellis/Sergios is the orchestrator of the operation, nurse Corti, a bear of a man, 230 pounds, six feet, two inches tall, is the boss. He has flown in from Los Angeles to administer the drug. He moves about the room in a black and white Japanese kimono and sandals. He carries with him the calm but intense bedside manner of the doctor-as-favorite-uncle. The bathroom sink is his lab table where he opens up a box of glass ampules containing the miracle drug, formally known as trichosanthin. There are two sets, one a dilute solution which he will use to test for allergic response, the second for a full strength infusion.

All four volunteers pass the allergy test and by 10 o’clock are ready to take the treatment. The two who have full-blown AIDS, Bob and Nick, know that this may be a last-ditch gamble. Both have essentially no immune systems left in their bodies and could suffer a fatal disease at any time. They also know that trichosanthin is itself potineially lethal and has never been formally administered to AIDS patients. The excitement it has provoed is based soley on test-tube experiments in which is seemed to kill the AIDS virus, and they understand that many, many drugs which work in the laboratory have little or no effect in the body.

Nick, a trim, tall man with deep inky eyes, is first. He drops his pants down about his knees. Brownish-purple spots, the cancerous lesions which are the mark of Kaposi’s sarcoma, disfigure his back and legs. At 47, he has moved to Ft. Lauderdale to live with his elderly mother who is herself frail. They are in a ghoulish race as to who will leave life first. Nick grips hard onto the shoulder of a friend, squints and sucks in a sharp breath as Corti presses the plunger of an inch-and-a-quarter hypodermic needle into his left buttock.

“O.K., honey,” Corti says, giving a friendly slap to the other buttock. “You’re a done deal.”

For the next two days there will be little to do but wait as Ellis/Sergios, Corti and two other volunteer nurses monitor the four men, note vital signs and pray that none will lapse into shock, or worse, the coma that an earlier volunteer had suffered, before they fall asleep. Fortunately, none has had a bad reaction, nor will they throughout the weekend aside from slight fevers and extremely sore buttock muscles at the site of the injections.

This weekend in Miami proved to be a rehearsal for the most remarkable, and in many eyes scandalous, operation of the AIDS drug underground. By the end of the month Corti and other activists launched a totally unauthorized treatment study of Compound Q, involving doctors, nurses and more than 40 patients in three cities, New York, Los Angeles and San Francisco. Some of the experimental treatments take place in doctors’ offices, some in “motel clinics,” and some in other elegant condos and houses of rich gay men. What is revolutionary about the underground operation is that unlike every other AIDS research trial, it is not sanctioned by the FDA, by state authorities or even by a local medical society. What is scandalous about it is that other, authorized safety studies of Compound Q underway at San Francisco General Hospital have only just begun. To encourage sick, even dying, patients to take a drug which is known to be lethal at sufficient doses, violates the most basic tenet of conventional medical research, namely that doctors must first do no harm.

Two years after the underground Q study ended, the drug has shown limited value. Some who continued using it, but who were generally healthy at the time they began, say they are better. Those who were sickest when they took it got little benefit. Most of them have died.

The formal, sanctioned studies which followed have shown mixed results at best. More telling than the clinical effect of the Compound Q operation, however, is its bearing on the place of disease in the lives of gay men. For of the hundreds of thousands of Americans infected with HIV, it is gay men almost exclusively who have entered into the universe of exotic medical treatments and who through force of will have reordered the way much of America thinks about medicine and care-giving.

Jim Corti, the smuggler nurse, says bluntly that for gay men, “there was no other way.” Born into a society whose medical establishment told them that as homosexuals they were “diseased,” then let loose as young men into the orgy of the bathhouse era, when gonorrhea was a minor inconvenience resolved with a cheap shot of penicillin, American gays have had fair reason to see themselves as outside the medical codes and systems that most other people lived by. It was not until 1973 that the American Psychiatric Association removed homosexuality from its catalogue of pathological conditions. Gays found little reason to expect equity or support elsewhere in the medical profession. Even in his famous, and at the time (1969) groundbreaking book, “Everything You Always Wanted to Know About Sex, But Were Afraid to Ask,” Dr. David Reuben dismissed “homosexuals” as sick, miserable people suffering from stymied development. Thus, to be homosexual was to be “unhealthy,” beyond the pale of medical normalcy. By the time of the great gay sex explosion in the mid-70s, it was no surprise that gay men with plenty of money, health insurance and prestige sought out public VD clinics–or private gay doctors running what amounted to commercial VD mills–rather than carry the annoying foibles of their sex lives to their regular straight doctors.

To most Americans, confessing a case of the clap was deeply shameful. Quite apart from homosexuality, it was a confession of consorting with the wrong kind of people. That you had the oozing pus repeatedly, four, five, six times in as many years, was not the sort of information you wanted your own doctor to know. And so, as in many other areas of gay life, homosex was cut off from the conventional territory of medicine and good health.

When the first purple lesions announcing AIDS, or as it was first known GRID (Gay Related Immune Deficiency), appeared, and men on the two coasts began losing their friends, the sex frenzy was at its height. VD clinics were running at peak capacity. Even though gay men were graduating from medical and nursing schools in greater numbers than ever before, there were not nearly enough of them to serve the rapidly expanding gay enclaves in New York, L.A. and San Francisco, much less the second wave communities in Miami, Houston, Atlanta, Chicago and New Orleans. Doctors and gay men remained, at best, suspicious of each other. When a handful of men organized the Gay Men’s Health Crisis in New York in 1981, they did so precisely because they saw too many of their friends dying and too few doctors and public health officials paying any attention. Not only did city health officials in New York and San Francisco show little interest in the fledgling AIDS epidemic. There was in fact, little they could say that would carry much credibility; the doctors seemed always to have been preaching against gay sex. Warnings that sex could give you cancer–in the form of KS lesions–sounded like just another barrage of homophobic prudery.

Even the gay activists who founded GMHC were denounced. One gay New York writer accused activist Larry Kramer of self-hating emotionalism because of his attempts to draw attention to the mounting toll of KS cases. “I think the concealed meaning of Kramer’s emotionalism,” Robert Chesley wrote to the New York Native, “is the triumph of guilt: that gay men deserve to die for their promiscuity …. Read anything by Kramer closely. I think you’ll find that the subtext is always: the wages of gay sin is death …. I am not downplaying the seriousness of Kaposi’s sarcoma. But something else is happening here, which is also serious: gay homophobia and anti-eroticism.” Kramer, as reported by writer Randy Shilts, responded that it was “stupid to rail against the very presentation of these warnings.”

The division between Kramer and Chesley over eros and disease, the tension between medicine and sex, ran through gay neighborhoods all over the country, especially in the major cities, and it shaped both the progress of the epidemic and of gay men’s eventual activist response to combating the epidemic. The most rancorous of the battles in San Francisco centered around the closure of the bathhouses in 1984. Leading gay activists denounced the bathhouse operators as little more than profiteering murderers, while the activists themselves who assisted the city health department in winning closure were called self-hating “quislings” who would eventually lead all gays into quarantined concentration camps.

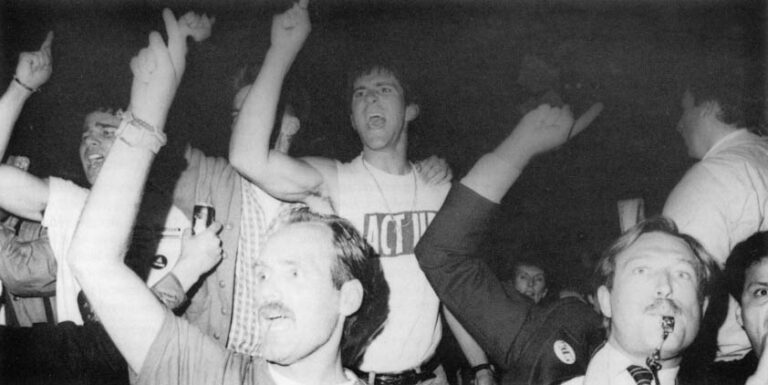

From within the rage, paranoia and confusion that marked the gay confrontation with AIDS, there emerged what can only be described as a land-shift in the dynamics linking homosexuality and health care. AIDS activists–almost all of them gay, ranging from the smugglers to the nurse caregivers were challenging nearly everything about the way health care is organized and medical treatment is delivered.

Never before had the patients hired their own buses to haul them hundreds of miles to Washington, D.C. where they would storm the government bureaucracy which regulated the drugs they could get. Never before had they organized their own international pharmaceutical distribution system to import the drugs. Never before had they sat on the official regulatory councils which designed the policies and regulations governing how doctors and hospitals and health insurers should treat them. And more, as they gained power over the vision and practice of health care, they managed not only to salvage but even to intensify the place of eros in health care, making hot sex central to a campaign for good health. Any residual doubt about the place of sex–hot, sweaty, raunchy sex–in the AIDS prevention campaign disappeared at the fifth global conference on AIDS in Montreal. For five days the discos were packed with gay doctors, nurses, activists and researchers shamelessly cruising each other. A nearby bathhouse was doing land-rush business. A JO (Jack-Off) Club posted promotional flyers in the conference exhibit hall. And in the middle of the conference exhibit hall there was the “safe sex” video sponsored by a West German health agency. It ran for two days, all day long and seemed never to have fewer than 25 or 30 viewers- men, women, straight, gay–gathered about the screen in a fidgety semicircle. Two blond men who might have been Michelangelo’s models were the stars, demonstrating a wide array of “safe” erotic possibilities. Many non-gay researchers and reporters at that conference were deeply puzzled over the amount of attention given to steamy sex by men who had such direct experience with the effects of this sexually transmitted disease. Yet to a considerable degree, those gay men who have committed themselves to trench duty in the battle against AIDS have done so exactly because they would not and perhaps could not relinquish passion to death. Simple survival as the whole gay men they were becoming forced them to face AIDS squarely and determine the limits to which they would permit it to control them.

Yoel Kahn, the young gay rabbi of Congregation Sha’ar Zahav in San Francisco’s Castro district addresses the issues of sex, death and identity straight on. As he sees it, AIDS has produced a spiritual and existential response directly parallel to the Holocaust.

“AIDS is like the Holocaust,” he says, “in that we have to go on living as though it were not happening, just as Jews in the camps could bear their existence only by living as though they were not facing death in the gas chambers and the ovens.” To live in the face of AIDS, to live in the communities where one of every two gay men had been infected and seemed, without a cure, sure to die, is to live a life of resistance. That life of resistance was at once spiritual, militantly political, and irrepressibly intimate in its sense of collective nurturing. Yet nurturing of what? Of sick individuals, surely. AIDS has flushed the newspapers and the airwaves with tales of great suffering and personal sacrifice, of heroic and tireless hospital teams like those on San Francisco’s famed Ward XX. The rabbi was claiming more: Not only to care for the fallen, but to go on living, as an act of positive resistance, not in denial of death and disease but in spite of it, knowing elsewhere in your mind that you will probably succumb to it. The act of resistance is the active assertion that gay human beings have not disappeared and are continuing to pursue the fullness of their physical, political, spiritual and emotional existences, acknowledging that the alteration of any one of these is not the same as the elimination of it. For the activists, nurses, researchers and community workers fighting AIDS to have excised sex from their lives would have meant succumbing to an existential death in advance of biological death.

Reed Grier was 30 when he first began to confront death among those closest to him. It was early in the epidemic, 1983, and Leo, a doctor, fell first, to cryptococcal meningitis, a fungal infection of the brain and spinal cord linings. Leo and Reed were part of an extended network of lovers and sexual playmates, the sort of arrangement that writer Edmund White once labeled the “bannion tree” model of gay family life. Five men were at the core: Reed, Leo, David (Reed’s original lover), Don (David’s final lover), and Stephen (David’s earlier lover who owned the duplex Reed and David shared and lived in the apartment below them). They were all white, all professionals, and all held advanced degrees: a health policy analyst, a doctor, two urban planners and a psychologist. Both Reed and David had had affairs and occasionally a joint tryst with Leo; it was Leo’s passing that removed death as an abstraction for them.

By 1983, Reed had finished a masters degree in planning at Berkeley, returned from fieldwork in Micronesia and in his own words transformed his relationship with David, a city architect and planning official, into “brother love.” They kept house together, ate most meals together, shared finances, but slept in separate rooms. Reed even introduced David to Don, also an urban planner and rugged outdoorsman. Don became David’s final lover and took a small room in their house. “It was an emotional menage a trois,” Reed says. “David and I were married. We shared a household together. We were family. I took care of him and he took care of me. I was his confidant in ways that Don never was. I knew his spirituality, inside and out. I knew all his fears and all his shadows, and he knew mine. He was there as a financial support and buffer for me. He really took care of me … to such an extent that he made provisions for me in his will.

“David was one of these people where every one of his ex-lovers turned into family, turned into this sort of brother-sister-friend who never left his life. David and I previously had been involved with Leo. Leo was our doctor.” Reed picks up a small figurine. “That’s where that came from. The bookcase behind you was Leo’s too.” He returns to David’s illness.

“First, David had to have an emergency appendectomy. He collapsed in the doctor’s office… a full-blown ruptured appendix. It was a four or five hour procedure, a type of surgery people don’t survive well that involves removing the entire intestinal system from the cavity and brushing it off centimeter by centimeter, flushing out the cavity so there’s no more gut in there. Then they don’t stitch you closed. They put in about five suture bars for spacing to kind of bring it together and put two drain holes in with tubes and then send you home. You take baths several times a day in a salty, sterile solution to draw the stuff out, and eventually you close from the inside out. That was the beginning of the caregiving.”

From that point on, Reed became David’s chief nurse and lifeline. At first a visiting professional nurse came to take David’s vital signs, and the service provided a social worker for counseling. “He’s going to die,” she told Reed one day. He fired her and the service, insisting that David was only in post- surgical recovery. In fact David never regained his health. “She was right,” Reed says in remembrance. “It ended up being one year of one thing after another until he died.”

The final siege came in the spring of 1986. Reed had been downtown at a conference on aging, discussing parallels between AIDS care and geriatric care. At 4 o’clock in the afternoon he called his answering machine and heard an urgent message. Don had taken David to the doctor where he had again collapsed and been rushed to Pacific Presbyterian hospital. Diagnosis: pneumocystis carinii pneumonia, PCP, the infection that most often kills AIDS patients.

Don and David’s sister Shelly were with him when Reed arrived. The doctor was explaining that David’s lungs were so blocked with pneumocystis that they showed white on the X-ray.

“What do you want us to do?” the doctor asked. “Do you want to fight one more time? Do want to go for it again? Or do you want to give up now?” “I want to go one more time,” David answered. “Let’s try one more time.”

David survived the hospital though he never regained memory of being there.

“I don’t know whether it was brain damage from oxygen deprivation in the [treatment] process,” Reed says in recalling the experience. “I don’t know whether it was HIV getting into his brain and causing dementia. I don’t know whether it was the cryptococcal meningitis reaching his brain. It don’t know whether it was MAI (a form of tuberculosis) which he also had getting into his brain. But he never recovered mentally from that hospitalization.

“We had to spoon feed him. Tapioca. Apple sauce. We had to toilet him … pick him up and put him on it. His digestive system failed. We had to give him medication a half hour before eating to start the process, then give him an anti-diarrheal after the meal to stop the whole process.” Meanwhile, David’s mind had gone away.

“Oh, gee, it’s really lovely,” he would say, looking out to the windows at blooming flowers. “This must be Switzerland.” Sometimes he thought he was in Australia. The more David lost his mind to dementia, the more Reed lost himself in saving David. Feeding. Wiping. Changing. Counting pills. Fixing doses. Only rarely did David speak. The David who was Reed’s soulmate, confidant and sustainer became the object of Reed’s care.

“I was in such denial about his dying, I couldn’t face it or see it coming,” Reed would tell his friends later. He found himself forcing the medication into David, on time, around the clock.

“I’d wake him up, lay all the pills out, give him a little sip of water, actually put it on his tongue. It got to the point where he was tonguing them. They’d go to the side of his mouth. They wouldn’t go down. I was almost sticking my finger down his throat to push them down.

“Then one night I screwed up. I’d put [the midnight dose] off to 2 a.m., and he was actually refusing. He said ‘NO!’ Like, ‘No, I don’t want to,’ or ‘No, not any more!’

“It was the first coherent thing we had in weeks. It was like, I’m PISSED. YOU’VE GOT TO DO THIS! YOU GOT TO STAY ALIVE! And it’s like, he won’t. Don is saying, ‘Let’s just let well enough alone’ and I’m insisting, ‘WE’LL AT LEAST GET THIS SERIES DOWN. WE’VE GOT TO GET THIS ONE DOWN! And I say, ‘I’ve got to tell the doctor about this.’ I go to bed furious. Angry! I’m angry!

“I call the doctor in the morning. And he says, ‘Stop all meds (medications)! He has told you it’s over. Stop all meds!'” From then on there was nothing to do but maintain David’s morphine-based pain relief.

A few nights later, around midnight, Reed heard light groans coming from David’s and Don’s bedroom. He went in. It was two hours early for his next morphine. David’s breaths were rapid, shallow, short, then followed by a deep gasp, then rapid, shallow, short, and another deep gasp, the Cheyne-Stokes syndrome that presages death. Reed gave him a half dose more morphine, checked his oxygen flow. At 2 a.m., Don came to wake Reed. “David’s died,” he said. “I just woke up. He’s gone.”

The two men cleaned their dead lover, wiped a drool of saliva from his mouth, put him in an old pair of jeans and a tee-shirt and wrapped an ace bandage around his jaw to hold his mouth shut. Then they placed coins on his eyelids.

Five years after David’s death, Reed’s voice breaks often in retelling the story. Midway through it, a watch alarm sounds. He pauses to take an AZT tablet, one of the many powerful and expensive drugs which have kept him relatively healthy. Drugs have not, however, saved the rest of his family. Stephen died six months after David. Don died last, three months before our conversation. Two years after David’s death, Reed entered an affair with a man named Ron. The first year was blissful, he says, but early into the second year Ron fell ill and died a few months later. There have been 38 deaths in Reed’s life. His remaining old close friends are heterosexual.

All of the dying has had a double impact on Reed. He seems reticent, even fearful of entering into any new gay relationships. He is not particularly optimistic about how much time he has left himself. AZT usually loses its protective value after two years, and at the time of our conversation it had been that long since be began using it. His T-cell count has remained strong–a good sign that he has at least a few more years of active life. Yet within that time, he explains, he cannot risk becoming the caretaker for another dying mate. The lesson of the last five years is that those he loves will leave him, that he will survive only to bury himself. Intellectually he knows that not every man he might meet will get sick. “I know it’s not true, but I’m afraid of connecting with people.”

There is another side of the relentless and premature gay death. For Reed Grier and uncountable others, AIDS became the agency of collective transformation. Not of an anti-sex maturation, as many straight observers began to report after the closure of the bathhouses in the mid-1980s, but as an integration of sex and communal caring. “Sex and desire are still a major portion of what makes us a community,” he says, “but it’s not the only thread anymore. Something else happened. You no longer necessarily look at another gay man as a sexual object, but as a brother, as someone who’s in this together with you, someone who has gone through this thing with you, someone who is facing the same issues of mortality, who is there to be cared for, cherished, nurtured, someone to be intimate with. Those are my brothers out there. There is a qualitative shift in the nature of the relationships between men in this city in the age group who’ve gone through this.”

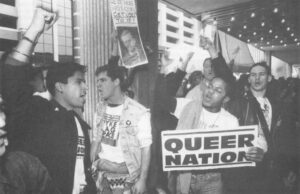

There are obvious examples of the institutions that gay men and lesbians built to defend and provide for gays stricken with AIDS. Food distribution. Home nursing. Legal aid. Shelter. Medical clinics. Even volunteer pet care services. Not to mention the activist organizations that smuggle drugs, stage street demonstrations and lobby city, state and federal governments.

The signs of transformation that Reed Grier sees take on a subtler and more intimate color. They are at once communitarian, spiritual and sexual. One of those signs is the emergence of new kinds of recreational sex clubs. Next to bars, bathhouses were the most prominent gay commercial institutions of the 1970s. Without their advertising dollars, few of the fledgling gay papers would have survived. Most of the bathhouses have closed, but in their place have emerged sex clubs. Like the baths, they are hunting grounds for recreational orgasm, and the men who use them are looking for something besides intimacy. Unlike the baths, where men walked around clad only in a towel, sex club patrons are generally fully dressed. The cold, objectified tyranny of the naked body that so dominated the bathhouses has been sheltered and clothed, and the responses between hunter and hunted have become more complex.

Men of varying ages (though mostly young) come in groups, talk and spend social time with each other, then wander off into quieter halls or corners. If the most common experience among men in the youth-obsessed baths was cold, public rejection, the more common gesture in the clubs is the affectionate caress which may or may not go further. The style of competitive prowess seems to have been supplanted by an ethic of shared adventure.

For Reed, the appearance of the clubs represents “a qualitative shift in how you relate sexually and personally. Everyone of these places has a different place on the continuum of desire, but the interesting thing about them as an archetype was this wonderful combination of a jackoff party where you’re getting down and dirty and being sexual, a cocktail party where you’re politely and very charmingly standing around and dishing things, a church social where you just hang out with a bunch of buddies-all wrapped into one. It’s all going on simultaneously. Somebody you start having a cocktail party chat with may end up 15 minutes later holding, cuddling and jacking you off and then later still come back and talk about the kind and price of fertilizer you’re putting on your garden.”

©1991 Frank Browning

Frank Browning, a freelance journalist from San Francisco, is examining gay culture in America.