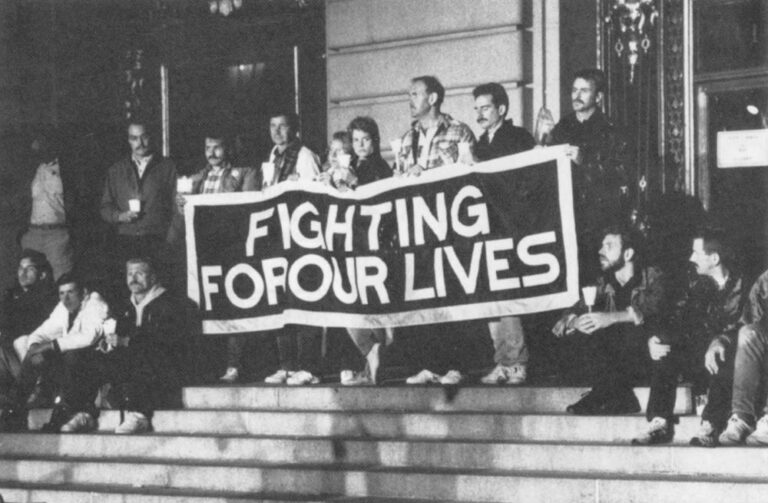

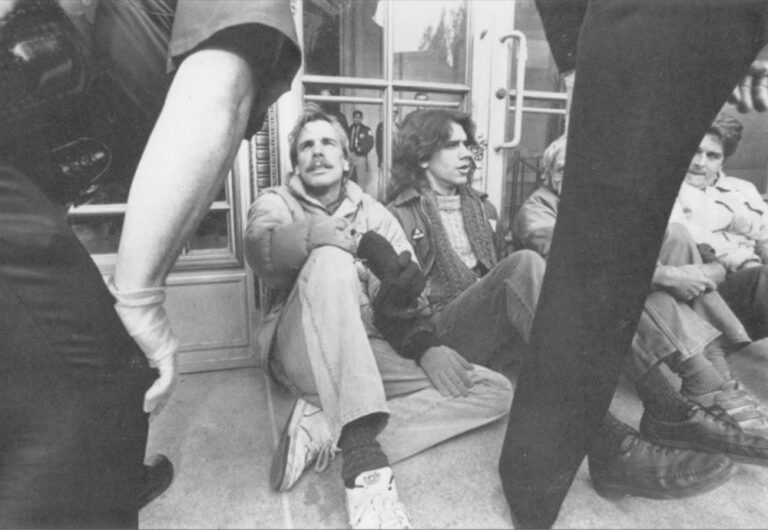

Photos by Marc Geller.

DISNEYLAND, CA–Eighteen-inch golden tresses fall softly atop the pleated, puff-shouldered blouse of an immaculately scrubbed and smiling Alice-in-Wonderland. Nearby, Cinderella, her hair in a bun, a black choke-band around her neck, looks on as Alice smoothes out the mock-linen gloves of a large, black-nosed six-foot mouse wearing a pointed Dutch-girl cap.

Closing in from behind the mouse comes a cheery young man, white shirt, bright spackled tie, creamy pleated trousers, carrying a thick docker’s rope.

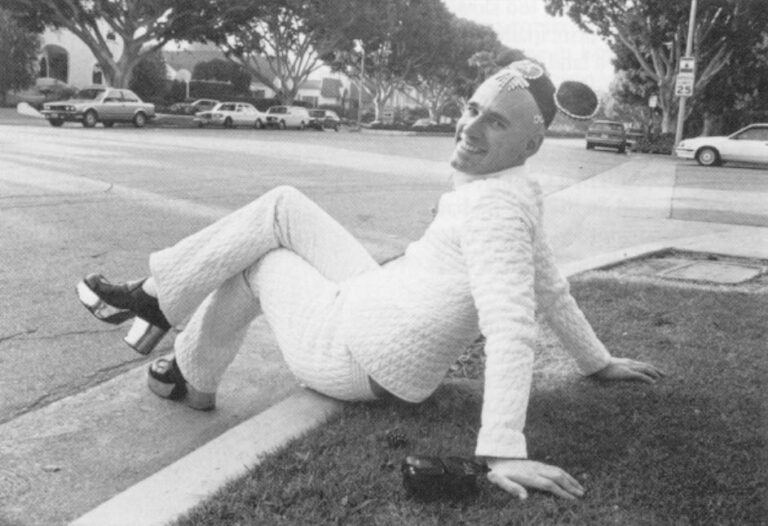

“Are you from Wonderland?” asks Alice, in the most incredulous sing-song voice, her query directed at the peeled head of a young man in a white-quilted leisure suit and 3-inch blue-mirrored platform shoes, the leader of a troop of drag queens and leather-boys who’ve staged this mid-winter raid on America’s most wholesome fantasyland.

“N-o-o-oh,” he answers with a verbal dip. “I’m from San Francisco. Can’t you tell?”

“Well, we simply must talk later,” Alice answers, traipsing off with Cinderella and the mouse behind the man with the heavy rope.

“Sometimes it’s hard to tell who’s really queer,” Ggreg Taylor, the man in the platform shoes, says later, adjusting his leather biker cap.

Ggreg-he always signs with a double-G–had hired San Francisco’s infamous hippy bus, the Green Tortoise, which for nearly two decades has criss-crossed the country as a rolling museum of the counter culture. For the weekend he renamed it the Lavender Tortoise and hauled 37 “fags, dykes and drag queens” into that heart of blinding cultural darkness, Southern California.

It would be, as one traveler wrote in San Francisco’s Bay Times, “a respite from the battles within battles facing this community’s various political activist groups, the occasional dreariness that sets in on our usually vibrant club scene, the sorrow of the constant loss of many loved ones, or the slings and arrows of life during wartime.” Or, more simply, a party.

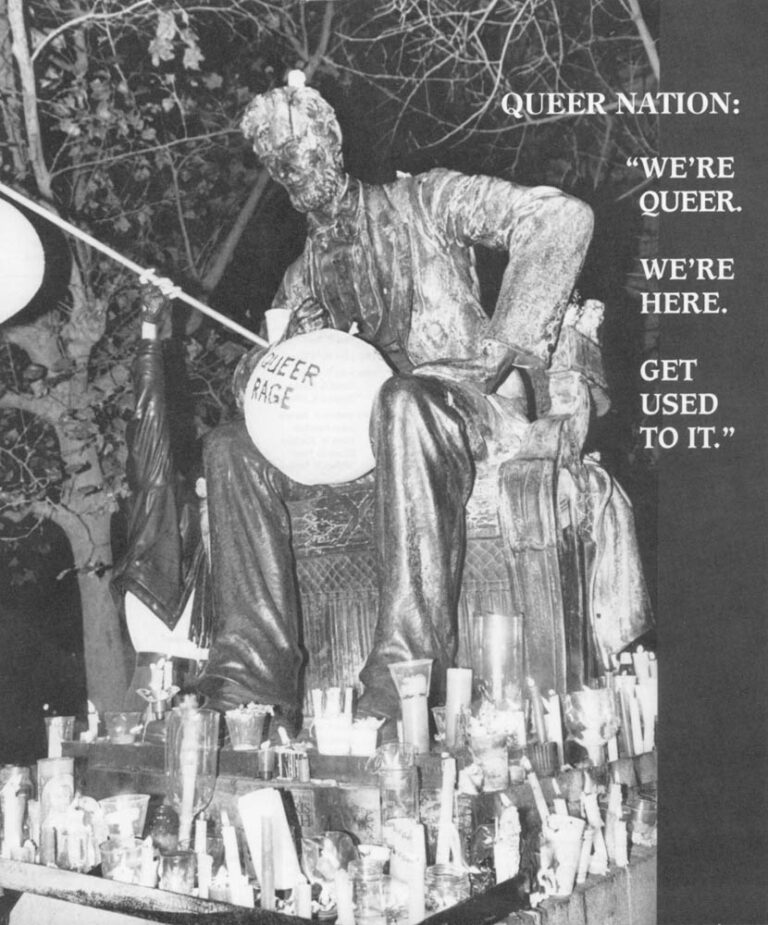

Ggreg Taylor and his band of kindred spirits are the court-jesters of a new, and growing “queer movement,” a young, angry, and at the same time irrepressibly playful part of the American gay movement. Reappropriating the most hateful words of homophobic denigration, they embrace the word “queer” and pin it to themselves as a badge of pride, visiting amusement parks, shopping malls and straight bars where they hold hands, caress, hand out peel-off stickers reading, “Promote Homosexuality,” or chant, “Fag Power! Dyke Power! Q-u-e-e-e-r NATION!”

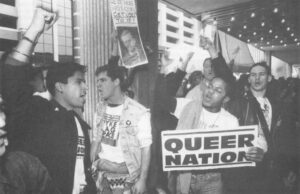

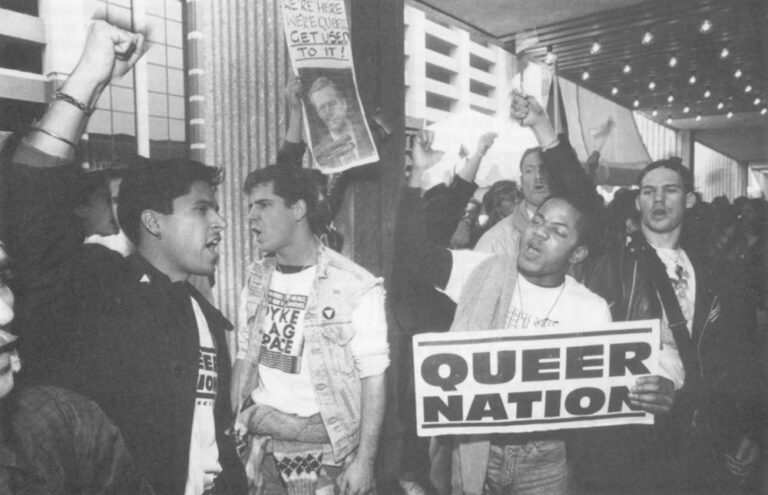

Queer Nation-a phrase which embraces both anger and irony- is also the name of the fastest growing gay organization in the country. In March 1990 it had not been born. By March 1991 more than 50 Queer Nation chapters had been established, not only in the predictable metropolitan centers but in more provincial cities that haven’t been used to seeing lumberjacks in sequins, towns like Salt Lake City, Albuquerque, New Orleans and Little Rock.

QN was invented as the stepchild of violence and television.

Early in 1990, Andy Rooney, the CBS “60 Minutes” funnyman, made his now infamous remarks about how blacks had “watered down their genes because the less intelligent ones are the ones that have the most children.” Rooney made the statement to a reporter for the Advocate, the national gay magazine.

The Advocate published the story in part to demonstrate that while racist statements from celebrities and public officials draw quick condemnation, antigay statements get almost no reaction at all. Gay activists had protested several times to CBS that Rooney regularly made anti-gay slurs, including one in his 1989 year-end commentary equating “homosexual unions” with such self-destructive behaviors as drug abuse, drinking and smoking. Rooney was temporarily suspended from the air, but nearly all the criticism of him–both inside CBS and in the subsequent press commentary–was just as the Advocate article predicted it would be. Rooney was condemned for his racial comments, but almost no one spoke of his hostility to homosexuals.

New York activist Alan Klein told a reporter that he realized there was “no mechanism to do direct action around homophobia,” and he began calling friends, many of them AIDS activists. Then a few weeks later the bombing of a Greenwich Village gay bar provoked an angry protest march. “I used ‘Queer Nation’ on the bullhorn that night, and it kind of took root with crowd…. It was a direct progression from AIDS activism to direct action for lesbians and gays.”

By July half a dozen “Queer Nations” had been organized across the continent. Jonathan Katz, a midwesterner by way of Washington and New York, helped create San Francisco Queer Nation. He sees QN and the new “queer movement” as a radical departure from older legal and civil rights styles of activism.

“We will not lobby Congress in the suits and ties of the dominant culture,” he explained at a gay and lesbian writers conference last winter. “We’re saying we refuse to accept the terms of the dominant culture. We’re here. We share the planet. If you don’t like it, fuck off.”

Katz, a 32-year-old with sharp-featured Tyrone Power good looks, was a young Washington lobbyist who tread the halls of Congress in suit and tie. That was 11 years ago when he headed a national association of student leaders. He went to the White House, took part in Democratic Party training programs, flew around the nation campaigning for student financial aid.

“I was sort of positioned in Washington to achieve what I had long hoped to achieve–a political career. Then I just decided that being queer basically made those goals impossible to achieve.

“I was not willing to be closeted [any longer] and I did not think that an uncloseted person could get elected to public office in the United States.” He adds that even today, Reps. Gerry Studds and Barney Frank, the only two openly gay men in Congress, were fully closeted when they were first elected.

Katz divides his time today between scholarship—he’s finishing a Ph.D. dissertation in philosophy and art history—and activism. He is not opposed to more traditional and polite forms of gay civil rights work, but he and others see the Queer Movement taking a much bolder step.

Surely the most vehement proponents of “queer power” are a group of New York AIDS activists who have begun talking seriously about arming themselves and taking target practice at Manhattan firing ranges. One of them is Robert Hilferty, a Princeton-educated filmmaker and veteran of numerous ACTUP demonstrations. Late last summer Hilferty was walking home on Houston street when a gang of six black and Latino kids attacked and brass-knuckled his friend in the head.

Neither man was seriously injured, but the steady rise in anti-gay assaults [a doubling of attacks reported to New York City police between 1989 and 1990] has convinced Hilferty that law enforcement is either unable or unwilling to protect gays. An unarmed patrol of men and women modeled after the Guardian Angels and calling themselves the Pink Panthers has been patrolling Greenwich Village streets since last summer. “But even that may not be enough,” Hilferty says. “I’m thinking of taking self-defense classes, even carrying a gun may be appropriate for some gay people who feel threatened.”

Hilferty acknowledges that most gays, and most of his friends, believe carrying guns would be counterproductive or might even provide an excuse to anti-gay police to fire against gays in street disruptions, but he warns that the level of anger over homophobic assaults within gay communities is rising.

“I won’t be surprised the day a gay man takes out a gun and shoots someone threatening his life…. I think it’s a viable self-defense option for many gay people. We’ve been talking about it. Let’s start doing it. What do you do if someone has a bat and broken bottles?”

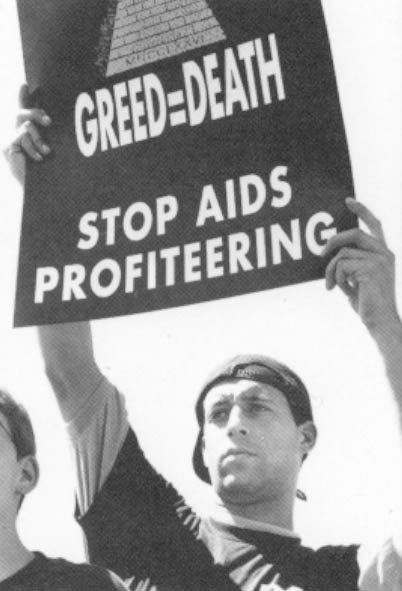

For Hilferty, for Jonathan Katz, and for many others there are sharp parallels between the gay experience of AIDS and the Jewish experience of the holocaust, parallels which led the activists who formed ACTUP (AIDS Coalition To Unleash Power) to adopt the pink triangle, the German death camp badge for homosexuals, along with the slogan, “Silence=Death.”

“Gay culture models itself on Jewish culture,” Hilferty says, “because they see the histories as similar. They see themselves as an oppressed people [who] have to politically organize themselves, make a place for themselves. [Gays] see themselves as wandering and scattered because gay people are born randomly around the world to heterosexual families and our sense of tradition has been scattered.”

In New York and San Francisco, where half the gay men have been infected with the AIDS virus, that sense of imminent death–of collective holocaust–is inescapable, and many of the angriest activists see the federal government’s slow response to AIDS in the early 1980s as a lightly veiled desire for the final elimination of homosexual people. “The perception is that real death has come from homophobia, because that’s what AIDS is, and fighting homophobia means saving lives,” Hilferty says.

There are other deeper, more complicated sources of the emerging queer rage. Part of it concerns dashed expectations- the promise of greater general tolerance built in the 1970s undercut in the 1980s by AIDS and rising anti-gay violence. Then, too, there is an absolute impatience with a consumer society that uses sex to sell everything from fancy wines to fanbelts, that posts sex-driven billboards next to every freeway but never publicly acknowledges the sexual existence of queer people themselves. As activist-artists like Hilferty put it, “queer people” are left to wander about in search of their own image, their own story, to seek and finally to invent new tableaux of their own identity.

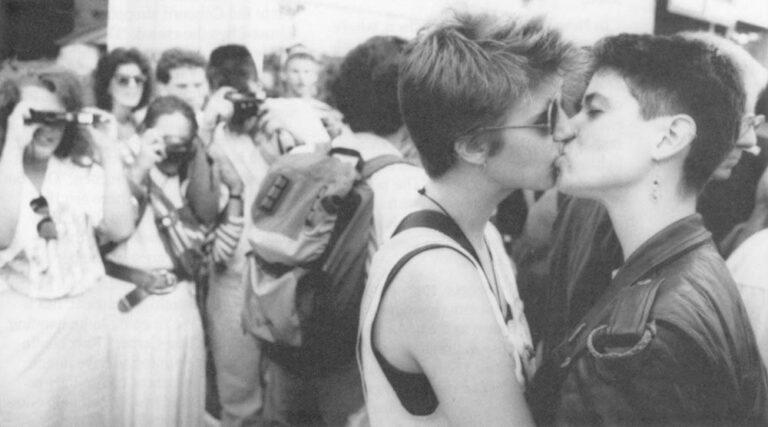

The scene is UN Plaza at San Francisco’s Civic Center last August a few days before schools reopened. About 45 men and a dozen women are milling around, some in black leather biker jackets bearing stickers that say “Promote Homosexuality” or “Fag Power” or “Queer Visibility.” A few other men in beards have donned plain hippy skirts. A lot of hair is bleach-blond and punk short-altogether a melange of Haight-Ashbury and Blade Runner.

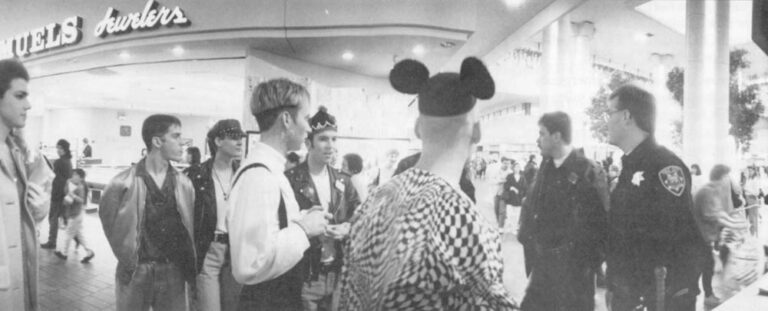

Jonathan Katz has the bullhorn, explaining that this Queer Nation back-to-school mission is there to introduce conservative suburbanites to the fact that queer people exist, and even more to let secretly queer kids who may be struggling with their identity know that they are not alone. The whole troop will board a noon BART commuter to head out to the Concord shopping mall. Katz admonishes the crowd: “Don’t go anywhere alone. We are deep behind enemy lines, in enemy territory–so don’t go anywhere without at least one other person.

Included in the literature they will distribute is a set of “math problems,” built around gay statistics. One goes, “One out of ten people is queer. There are 16 cheerleaders on the home team. How many queer cheerleaders are there–round off to the nearest whole person.”

The tone is non-confrontational, playful, ironic and thoroughly theatrical. But it has an edge. “We’re going to be handing out ‘Queer Calling Cards,’” Katz continues, “and they’re going to have phone numbers for all sorts of community resources … mental health, self help coming out groups.

“Again, we’re there for Back-to-School days, and we’re specifically there to recruit the kids. So we need to pass out that literature.”

Both Katz and the crowd know just how provocative that line is, how deeply it taps into and confronts conservative paranoia that all homosexuals are lecherous pederasts out to steal innocent children. They know they are playing with the same anxieties as they march through the mall chanting, “TWO, FOUR, SIX, EIGHT! HOW DO YOU KNOW YOUR KIDS ARE STRAIGHT?” The slogans and the tactics use playful, camp irony to shape the harder, more provocative edge of the new queer movement.

“I think we need to be understood as a threatening and perhaps unpredictable social force,” Katz said. “I’m entirely behind a politics that keeps them wondering about us. For me change is about power, and I want to protect that image of power.

“Playfulness is part of that unpredictability. What I’ve been trying to do within the group is to reinforce AGAIN AND AGAIN that my culture ain’t your culture, straight people. My modes of operation aren’t yours, and you better get used to seeing us the way we operate, according to our codes, according to our rules.”

Anger and playfulness merge in the movement: anger at their own memory of adolescent isolation and their continuing invisibility at shopping malls and supermarkets; playfulness as a technique for letting other young gays and lesbians know that they can find a rich, interesting and positive life once they leave their heterosexual families.

It’s 10:15 Saturday night at the Coral Sands, a just short of tacky gay motel in east Hollywood where “straight-acting” husbands, businessmen and tourists come for fun with men away from home. On this Saturday night, CNN is recording Gen. Norman Schwarzkopf’s rout of Iraqi troops from Kuwait, and Ggreg Taylor totters on his blue-mirror platform shoes along the pumice-stone edge of the pool, talking strategy for the next day’s queer excursion into Disneyland.

“Be positive, pro-active,” he instructs, going though his routine as drag adviser and tour coordinator.

“It’s the happiest place on earth,” shouts Tyler Bob, part of a punk performance group called the Popstitutes.

“Exactly,” Ggreg grins. “I want to be queer. I want to be militant, but we’re gonna have to cover it going in. Once I’m inside I plan on zipping up my jacket and start looking like I’m in a space outfit.

“Now one thing: We’re going to push the limits of heterosexism. You can do what the straight Couples can do there. Straight couples can’t deep-tongue kiss there. Nooooo! They can hold hands. They can pet. You can’t make out in the park–it’s a family atmosphere. So I encourage everybody to have your hands around each other. Hold hands!”

Somebody warns that if they start sticking the Queer Nation “Promote Homosexuality” stickers around Disneyland they could all be bounced out.

“Don’t sticker inside the park! If anything be educational not confrontational. It’s not that I want to be good queers, but I think that we’re groovy and we’re hip, and I’m out to use drag-outreach to fight queer invisibility and educate these tired people from Des Moines who’ve never seen a phenomenon like us. We are everywhere and we have come to you.”

Most everybody has heard Ggreg’s behavior litany before. No one disagrees with the keep-cool strategy, but after an hour or so, the meeting breaks. Ggreg announces it’s time to find his party clothes and hit Hollywood’s “underground” queer clubs. Most of the crowd heads for their makeup kits, a few to search out sexual adventures among the rest of the motel’s clientele.

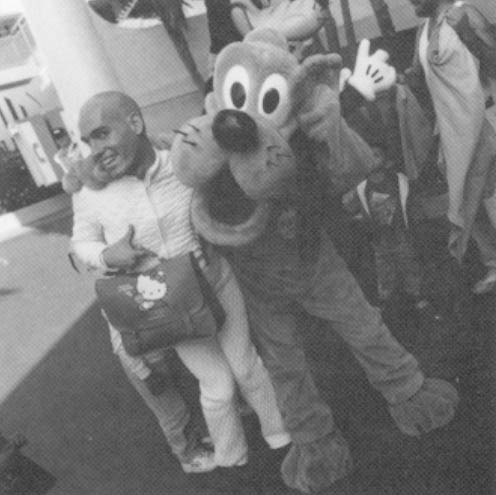

Next day Disney security people, their names inscribed on badges shaped like mouse ears, are ready when the Green Tortoise bus disgorges the queer entourage at the park’s monorail entrance. Despite park rules prohibiting visitors from wearing costumes, they stop no one, not even Rod, a tall man wearing heels, a purple brocade shirt, pancake makeup and dark glasses. The only person asked to change her garb is a young woman from Santa Cruz whose T-shirt reads, “Nobody Knows I’m Gay.”

Inside, other tourists seem friendly or curious or uncertain whether the queer folk are simply another part of the Disney show. Disneyland staff, especially those in animal outfits, go out of their way to be friendly, offering lots of nods and winks which lead Ggreg Taylor to wonder how many are actually straight.

A few minutes after Taylor, Cinderella and Alice (in Wonderland) finish chatting, several teenage boys draw close, staring at a man who goes by “Diet Popstitute.” (Diet’s name is spelled out in magenta hair on the back of his otherwise shaved skull; he’s wearing a green polyester suit, pink sneakers.)

“That’s BAD,” one of the teenagers says to his buddy. Then, looking closer, he gasps, “They’re fags!,” and gives out a delighted mock scream as though he’d just spotted an egret riding the roller coaster.

©1991 Frank Browning

Frank Browning, a San Francisco freelance writer, is examining gay culture in America.