October, 2013

Muern Sarun’s parents had turned down several offers of marriage when they asked a motorbike mechanic named Rous Savy to take their daughter’s hand.

Rous had taken a liking to Muern after she parked in front of his house in Cambodia’s Kandal Province on her way to weave scarves on a friend’s loom. Rous began visiting so often that the neighbors began to gossip: “Who would marry [Muern] if there is a man that goes to her house so often?” Rous quickly got the necessary permissions from the police and village chief, who granted the marriage certificate after Rous was able to reassure them that he would be able to support a family. Rous’ mother helped organize the wedding, which included blessings from four Buddhist monks.

This would be a fairly typical story about a Cambodian marriage, except that Rous Savy was not born male. He had long dressed like a man and referred to himself in male terms, but he was what is known in Cambodia as a “tom.” Gender and sexual orientation categories in Cambodia — as in much of Asia — don’t neatly line up with the terms used in the West. Some toms would probably identify as butch lesbians in the West, while others, like Rous, speak about always feeling “like a man” and would probably be considered trans men.

The wedding caused a sensation in Muern’s village as gossip rapidly spread about her groom’s gender. Muern recalls “4,000 or 5,000 people” came to witness the curious event. Muern had shelled out to hire a special band for the day, but the gawkers showed little interest in the expensive entertainment. Instead, many of the guests were occupied by placing bets on whether Rous was really a man or a woman. Muern remembers many people approaching her to ask: “You are so adorable! Why would you marry someone of the same sex?”

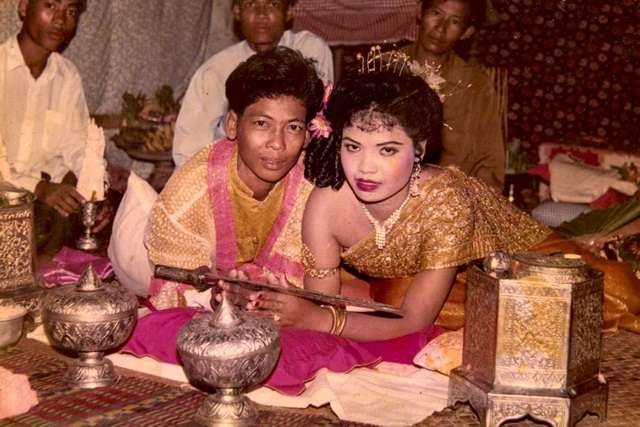

Muern, who was 17 when she married, looks regal in photos from the wedding. Her black hair, swept high on her head, is crowned with a tiara, and her cheeks and lips are painted a rosy red. She wears a beige skirt and a lacy wrap with golden bangles around her wrists, upper arm, and neck. Rous wears a blue double-breasted suit, which hangs loosely on his wiry frame. Though he was a decade older than his bride at the time, in the photos he looks like he could be her kid brother.

What makes their wedding even more remarkable is that it took place in 1993. Same-sex marriage was just beginning to become thinkable in the West; it was only in 2001 that the Netherlands would become the first country to grant same-sex marriages. Cambodia was not particularly advanced, to say the least, on human rights at the time. The country was just emerging from a period as a protectorate of the United Nations, which took control after the country had weathered three catastrophic years under the Khmer Rouge followed by a decade of occupation by Vietnam. The constitution adopted that year expressly banned same-sex marriage, and the country’s LGBT movement remains in its infancy to this day.

Muern and Rous were not activists taking a stand with the backing of an organized movement, as so many same-sex couples who sought to marry in the West have been. They were simply a couple who wanted to be together, and they used the only avenue available to them: marriage. They got lucky that their families and local leaders sanctioned the relationship (despite national policy) — family rejection, forced heterosexual marriage, and gruesome violence threaten LGBT people in Cambodia as much as they do in many other countries.

The couple is not entirely unique. The same weekend I met Rous and Muern, I met Peng Sanh and Un Sreyphai, a couple that has been together for 34 years. They fell in love while doing forced labor on a commune set up by the Khmer Rouge. Their commune chief refused to register them as spouses after the Khmer Rouge fell, but did agree to register them as siblings on official documents, thus giving them the right to live together. Hout Kem Hong and Thuch Sreytouch also bribed their commune chief $20 — a hefty sum in one of the world’s poorest countries — to register as siblings, and the chief has recently promised to re-register them as spouses after Cambodia’s election is settled. (The outcome of the July 28 vote is still in dispute.) Their family book also includes the four children they have raised. Three are Thuch’s nephews, the last Hout conceived by having sex with a man so the couple could have a biological child.

These couples owe much of their success in getting some level of official recognition to Cambodia’s rampant corruption and lawlessness — local officials can do more or less what they want regardless of national policy. But the past few decades have seen stories of same-sex couples — especially lesbian couples — attempting to formalize their relationships across Asia, from India to Indonesia. In many cases, these couples risk arrest and violence. Many cases end in tragic stories of suicide by couples who have no way to escape being separated.

These stories show that despite the fact that all the countries that have legalized same-sex marriage, with the notable exception of South Africa, are in Europe and the Americas, the West did not invent same-sex marriage. Nor is it a “cherry on the sundae” of LGBT rights, as same-sex marriage has sometimes been described — an important prize, but one that is only worth pursuing after sodomy laws are struck down and other more basic rights are won. Many gay, lesbian, and trans people in Asia live in areas that lack organizations centered on fighting for their rights. Many don’t have the money or ability to run off to the city. In much of the world, marriage is an inevitable part of life, something expected and often organized by families. And there are often no imaginable ways for people to support themselves without a family unit. Taking the risk of marrying the spouse of one’s choice is the most obvious way to resist being forced to marry someone else.

* * *

The modern history of same-sex marriage in Asia goes back several decades. Since at least the 1980s, there have been reports of couples performing marriage rites in secret or even holding large public weddings. Often these stories made headlines because they ended tragically — couples were arrested, kidnapped, and forcefully separated by their families, or even driven to commit suicide.

One of the best-known cases came in 1987 in India’s Madhya Pradesh, which made headlines across India. Two police constables named Leela Namdeo and Urmila Srivastava exchanged vows at a Hindu temple in the city of Sagar in a ceremony conducted by a Brahman. The two women took turns placing garlands around each other’s necks, a Hindu ritual equivalent to exchanging rings. They went to a photo studio to have pictures taken of the garland exchange, something that would have legal as well as sentimental value; marriages in India do not require government registration, so such photographs are often used as proof in cases where marriages are disputed.

The story of Namdeo and Srivastava might have stopped there if a jealous co-worker hadn’t stolen their wedding photo and given it to their police commander. The two women were imprisoned — theoretically for violating the country’s sodomy law, though the law only criminalizes sex between men — kept without food for 48 hours, and then fired and forcibly removed to Srivastava’s village, supposedly because they were a bad example for other women on the police force. The harassment had been so severe that, within a few months, the couple began disavowing they had ever got married in the first place. They started telling people they were friends who were playing around when they decided to have the wedding photograph taken.

The marriage of Namdeo and Srivastava is just one of dozens of same-sex marriages attempted in India over the past four decades and documented by academic Ruth Vanita in her book, Love’s Rites. Many others ended far more tragically.

In 2000, Bindu and Rajni, two twentysomething women from the south Indian state of Kerala, tied their bodies together with a dupatta, a women’s scarf, emulating another Hindu wedding custom. They had tried, and failed, to elope a few days earlier. They then threw themselves down a granite quarry.

Similar cases continue to unfold around the region, often in places where the LGBT community is most embattled. At least 11 couples have tried to marry in Indonesia in the past three years, according to Andhanary Institute, a Jakarta-based queer women’s organization.

This includes a 2011 case from Central Java, in which a 26-year-old trans man known as Rega wound up in jail after the family of his bride “discovered” he was born a woman on the day of his wedding. His 17-year-old bride, identified in news reports as Siti, claimed she had no idea that her groom was biologically female even though they had had sex repeatedly while they were dating. Rega was charged with fraud and having sex with a minor, and was forced to hold up the sex toys he used to “trick” Siti during the trial. He wound up serving 18 months in prison.

* * *

The first Asian nation to legalize civil unions could be Vietnam. The government in Hanoi has already endorsed civil union legislation, which is expected to be voted on by the National Assembly in the spring.

Thailand’s parliament is also working on a civil union proposal, though activists involved in the effort say shortcomings in the proposals and disagreements between activists over strategy may derail the legislation. The proposal would only allow same-sex unions, meaning intersex or transgender individuals might still have difficulty marrying. It also doesn’t provide adoption rights, and has a higher age of consent than that applied to heterosexual couples seeking to wed. Some activists are still hoping the law will come to a vote to force debate, but others oppose it outright.

Marriage equality could be a point of intersection between Western and Asian activists. And yet the topic of marriage makes Western LGBT activists working internationally uncomfortable: Many frequently warn that marriage is a volatile issue and pushing it abroad can backfire. Their caution is largely borne of the experience where reports or mere rumors of same-sex weddings can provoke anti-gay legislation or lynchings of people suspected of being gay.

There is no doubt this threat exists in many countries, especially in Africa. The most blatant evidence of this at the moment may be the “Anti-Same-Sex Marriage” bill, which has passed the Nigerian legislature and is awaiting the signature of President Goodluck Jonathan. In reality, it would increase penalties for same-sex relationships of any kind and even criminalize advocating LGBT rights and public displays of affection.

But the rhetoric of many LGBT rights activists often suggests that marriage is a concern to a narrow portion of the world, while the rest of the world pays for that desire.

After the U.S. Supreme Court decided to strike down the Defense of Marriage Act in June, Jessica Stern, the executive director of the New York–based International Gay and Lesbian Human Rights Commission, said the move made them “rejoice.” She then quickly tempered her enthusiasm:

In countries where discrimination against LGBT people is high, the decisions are likely to be used dangerously against LGBT individuals, organizations and human rights defenders…Over the last decade, allegations of “gay marriage agendas” and/or “gay weddings” have been used to crack down on social gatherings attended by LGBT people and to crack down on free speech, assembly, and access to life-saving information on HIV/AIDS.

Alistair Stewart, assistant director of the London-based Kaleidoscope Trust, was more blunt. “Gay Marriage and Other Wins for LGBT People Here Are Making Life Worse for Gays and Lesbians in Developing Countries,” he titled his Huffington Post July column.

Inside the countries where same-sex couples have tried to marry, these concerns also exist — particularly in countries like Malaysia, where Islamists have considerable sway, adding to fears that raising the issue could do more harm than good.

Yet other concerns exist: in countries as varied as India, Thailand and Singapore, many lesbians and feminists argue that marriage shouldn’t be a goal because it is associated with practices like forced marriages, child marriage, and domestic violence.

“I don’t believe in marriage as an institution, especially marriage as it is in India,” Sumathi Murthy, a queer feminist activist in Bangalore who helped found the organization LesBIT, said in a recent interview. “There are lots of other issues: Even now lesbians are committing suicide, trans people are facing severe violence, and discrimination is going on with a very heavy hand.”

Yet throughout much of Asia, it appears that women and trans men who most frequently try to access the institution. There are a handful of cases involving gay men or trans women, such as a 2011 Indonesian case in which a trans woman known as Icha was jailed after her husband claimed she had lied to him about being a woman and tricked him into marriage, presumably because he was afraid their relationship would be discovered. And in Taiwan, a marriage case involving two men was headed to the country’s top court until they abruptly dropped their lawsuit last winter.

But most of the cases — at least those that make headlines and come to the attention of activists — seem to involve women and trans men. This may be because men in many of these countries have far greater freedom to manage, or avoid, family pressure to marry. Men often have the option of leaving home, living on their own, or marrying a woman and having sexual relationships outside their marriage. Women’s life choices are frequently far more constrained, especially if they are poor, uneducated, and live in rural areas: Many jobs are off-limits to them, their sexual behavior is closely monitored by friends, and their physical safety is constantly at risk.

Men “have the luxury of going to a completely different city and being themselves — their family will never know,” said Sunil Babu Pant, founder of Nepal’s Blue Diamond Society, one of Asia’s most successful LGBT organizations. “But for girls, living at home, you must give explanation. Only when they get desperate and they leave [to marry another woman], then it becomes a case.”

Pramada Menon, who helped found the New Delhi–based feminist human rights organization Creating Resources for Empowerment in Action, said that most of the lesbian couples who have tried to marry in India show “marriage per se … is the only visible way in which [most] people can actually live together and that is the only understood framework,” though she is also no big fan of the institution.

Six weeks after the Supreme Court struck down DOMA, I was in Phnom Penh and met Hout Kem Hong and Thuch Sreytouch, two women who had been together for 26 years and had adopted three kids, but had only decided to have a wedding ceremony in 2011.

I thought perhaps they had heard about marriage equality victories abroad and decided they could have a ceremony too. But when I asked, they answered just like Muern and Rous had: They said they didn’t know same-sex marriage was legal anywhere — they hadn’t even heard about the Supreme Court ruling a few weeks earlier or the marriage equality laws passing in Britain and France.

Their decision to marry was much more simple. “We celebrated [a wedding ceremony] because we wanted to live with each other by following Cambodian tradition,” Hout said.

© 2013 J. Lester Feder