It is a time of troubles once again, and for the fourth time in fifty years preventive detention has been imposed in Northern Ireland.

The knock on the door that many had long expected began to be heard a couple of hours before dawn on August 9th, By mid-day nearly 300 persons – all men and all but a handful Roman Catholics – were in Custody. Some were freed within 48 hours, and some will sooner or later face ordinary criminal charges before ordinary courts.

The rest face internment for an indefinite period. They will be charged with no crime. They will have no right of habeas corpus or trial by jury. They will have no right to see an attorney or any member of their families, no right to send or receive any communication.

For they are suspected of acting or having acted or being about to act in a manner prejudicial to the preservation of the peace and the maintenance of order in Northern Ireland. Under the Special Powers Act, anyone so suspected – who knows by whom?–may be interned or subjected to lesser penalties such an house arrest whenever the Minister of Home Affairs considers it “expedient” (The quotations are from the Act.)

In one sense, it seemed so on this occasion, for something drastic was obviously required. Northern Ireland’s civil strife is well known, but a couple of reminders may be in order. About 150 bombings occurred in all of 1970; about the same number occurred in the first half of 1971, and the bombs and consequent destruction were larger. In all of 1970, about 100 soldiers were wounded; in the first seven months of 1971, about as many were wounded, and 10 were killed. And August 12, when 100,000 Protestants would march, often near or straight through Catholic areas, was still to come.

Whether it will prove expedient in a second and far more important sense – whether it will be effective – is much more doubtful.

In announcing internment, Prime Minister Brian Faulkner, who is also Home Affairs Minister, outlined what he thinks can and must be achieved. He said in part:

“We must sustain a continuing program of economic and social development, and we must find the means to create a more united society here, one in which all men of good will, however divergent their legitimate political views may participate to the full….

“Neither will be possible in a climate of terrorism and violence…and I have had to conclude that the ordinary law cannot deal comprehensively or quickly enough with such ruthless viciousness….

“I have taken this serious step solely for the protection of life and the security of property…. This is not action taken against any responsible and law-abiding section of the community. Nor is it in any way punitive or indiscriminate. Its benefits should be felt not least in those areas where violent men have exercised a certain sway by threat and intimidation over decent men and women….

“The main target…is the Irish Republican Army, which has been responsible for recent acts of terrorism, and whose victims have included Protestants and Roman Catholics alike….

“I cannot guarantee that the action we have now taken will bring this campaign (of terrorism) swiftly to an end. We may yet have much to endure as a community; but if we endure it with courage and steadiness the utter defeat of terrorism is sure.”

Mr. Faulkner announced prohibition of most parades, including the Apprentice Boys’ march, for six months, and said, “We are, quite simply, at war with the terrorists, and in a state of war many sacrifices have to be made.”

He then addressed himself directly to my Catholic fellow countrymen, saying, “I do not for one moment confuse your community with the IRA or imagine that these acts of terror have been committed in your name or with your approval…We are now acting to remove the shadow of fear which hangs over too many of you. I appeal to you to come out and join us in building this community up again; not to restore it simply to what it was, for many of us in the past have failed each other, but to build it on better, sounder, and stronger lines….

“Over the last couple of years we have taken many steps to make it clear that we want all the people of Northern Ireland to play a part in administering and developing the country. But neither changes in law nor changes in administrative structures can unite this country until we defeat, and unite to defeat, those violent men who seek to divide us….”

In short, reforms have been made and will continue, and the small band of terrorists will be defeated.

The short reply is that hardly anyone believes Mr. Faulkner is both sincere and accurate, and it is easy to see why.

It is hard to take seriously a call to “come out” (revealing phrase, that) and unite the community from one who doesn’t intend to leave the Orange Order and who saw no reason not to march with his local chapter on July 12–though the Order is openly and determinedly anti-Catholic, and though he had had to plan to leave the march early to oversee police action against rioting he knew the march would trigger.

It is hard to believe internment is not punitive and not aimed at one section of the community when Catholics are locked up but the Ulster Volunteer Force and the Shankill Defence Association are ignored.

(The UVF is a Protestant private army, theoretically outlawed but, like the IRA in Eire, rarely bothered by police. The SDA is one of the Vigilante groups that have appeared on both sides but stands out because its leader, John, is notable, even in Northern Ireland, as a ranting bigot. He defines Protestant as anyone who hates Catholics, and proclaims that the best Protestants are ones who have killed Catholics.)

It is true that Protestant parades have been banned, but that just in not equivalent to internment.

It is hard to believe in promises of economic and social development when unemployment, which has fallen below 6% only once in the last 21 Years, is now at 8.5% and rising (an appalling enough rate, but among Catholics it is nearer 12%); when public and private investment are certainly not increasing and may be decreasing; when 40% of housing is classed as “slum” or “lacking a basic amenity” (such an a toilet or hot water) but public spending on housing has declined in the last two years.

Above all, it is hard to believe in political reforms when the crucial ones concerning elections have not been implemented. There are two issues here – universal adult suffrage, and fairly drawn election districts. They are of course related, but the fact that both are at stake, when either is sufficient to tip a balance of power, goes a long way toward explaining why conditions in Northern Ireland are so desperate.

One way the Unionists have prevented any effective challenge to their power for fifty years was by maintaining three distinct electoral rolls. The first, for the Parliament at Westminister, was open to all as required by United Kingdom law and contained just under 910,000 names in 1967. The second, for the Parliament at Stormont, was also open to all, but was loaded slightly by retention of the business vote (i.e. a vote available to corporations according to their wealth) which added nearly 24,000 votes (2.6%) to the total, most of then Unionist votes.

The third was for local government – where the major decisions on housing were made. The business vote was retained here too, but in addition a minimum property qualification was imposed. Only those who paid rates (property taxes) could register. Because Catholics are on average poorer than Protestants, more Catholics were excluded, and on both sides the overall effect was to exclude the not-so-prosperous and the young. It was very effective, for it denied the vote to 239,000 (25.6%) of those on the Stormont register.

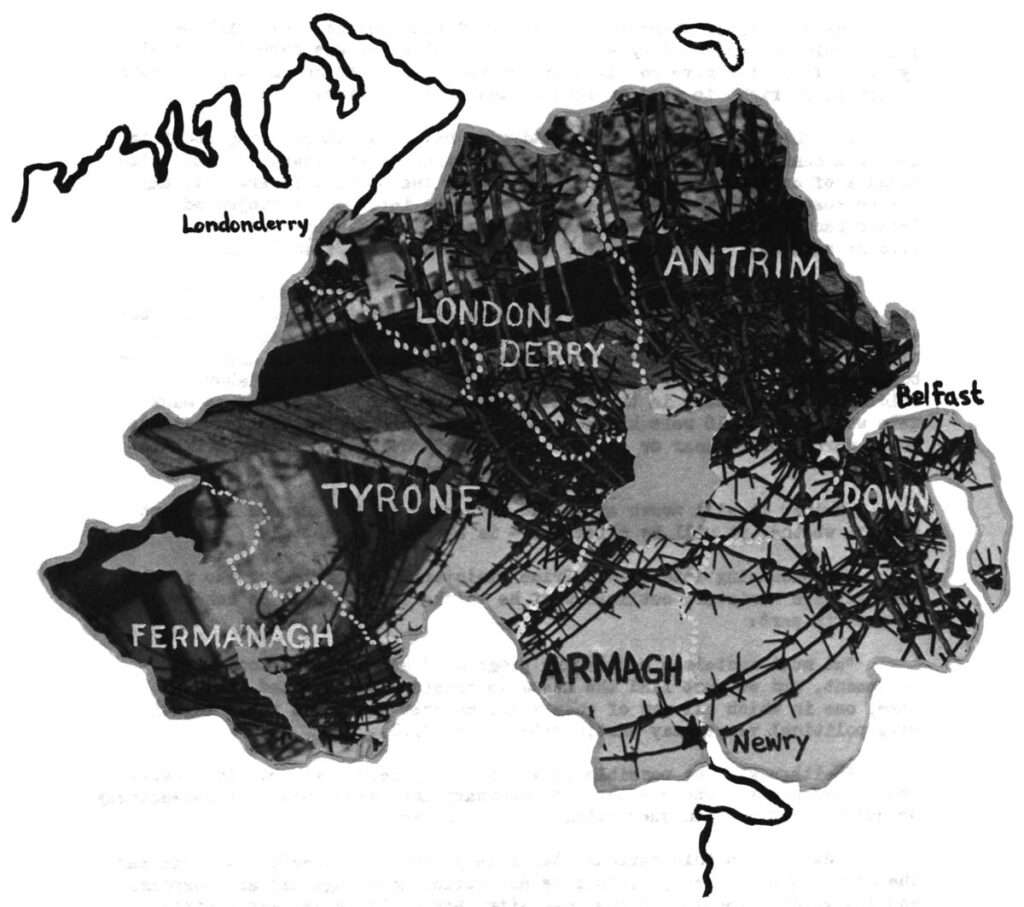

Even so, Catholic majorities remained in some places, so they were gerrymandered. For instance, in county Fermanagh, where Catholics comprise 53% of voters, Stormont and county council districts have been drawn so that two of the three MPs and 33 of the 50 councillors are elected by the Protestant minority.

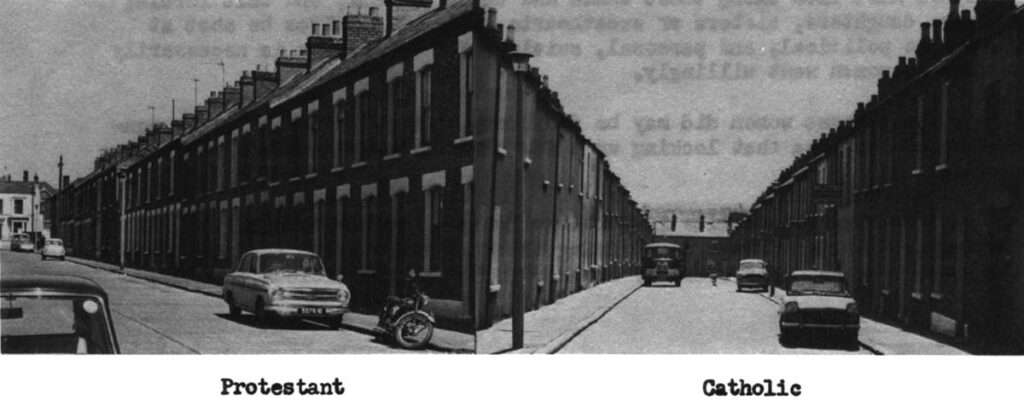

The effects were severe. Lim de Paor reports in his book, Divided Ulster, that between 1945 and 1969, a total of 1589 council houses were built, of which 1021 (64.3%) were allocated to Protestants. Of the council’s 370 white collar employees in 1969, 338 (91%) were Protestants.

Londonderry was still more blatantly carved up. In 1961, the borough electorate totaled 23,210, of whom 14,432 (61.2%) were Catholics. But the Protestant minority elected 60% of the councillors. The following chart shows how it was done:

| Catholics | Protestants | Councillors | |

| North Ward | 2,530 | 3,946 | 8 Protestant |

| Waterside | 1,852 | 3,697 | 4 Protestant |

| South Ward | 10,050 | 1,040 | 8 Catholic |

(Later, Waterside was given four more councillors, making the Protestant majority a full two-thirds. That gilded the lily overmuch and after the civil rights marches a non-elective commission was imposed by central government.)

Legally, the Property qualification and plural votes were done away with in November, 1969. And new election districts are to be drawn up when local government is completely reorganized (probably in 1972), and interim boundaries for existing bodies may be redrawn under legislation passed in March of this year.

But so far it is only sound and fury because local elections have twice been postponed. The 1970 contests were put off on the grounds that campaigning might inspire, or be made impossible by, renewed violence. The ones scheduled for 1971 were postponed to await the reorganization of local government, which means until late 1972 at the earliest.

Convenient reasons are sometimes true, but it is not surprising that after 50 years of deliberate exclusion by the Unionists, Catholics are not convinced by any excuse for further delay.

The point is not that Mr. Faulkner has no case at all. In fact there have been reforms and some are important. The infamous B-Special force is gone. The regular police have been disarmed. The allocation of housing is no longer a local government matter. The Londonderry Development Commission has made progress – reporters who saw the Bogside in 1968 say its appearance has changed tremendously. Parliamentary and local government commissioners (ombudsmen) are functioning, as is a Ministry of Community Relations, and these offices can have some impact now that most governmental bodies have formally adopted policies of non-discrimination in employment.

Nor is the point that Mr. Faulkner is dishonest. I think that he probably does believe most of what he said. If Catholics are understandably unimpressed by reforms that have been written but not implemented, Mr. Faulkner is understandably impressed by how much the statutes have been changed.

Moreover, he earned some presumption of sincerity with his proposals of June 23, 1971, particularly one to modify simple majority rule at Stormont by giving Catholic members certain committee chairmanships and thereby some access to effective power.

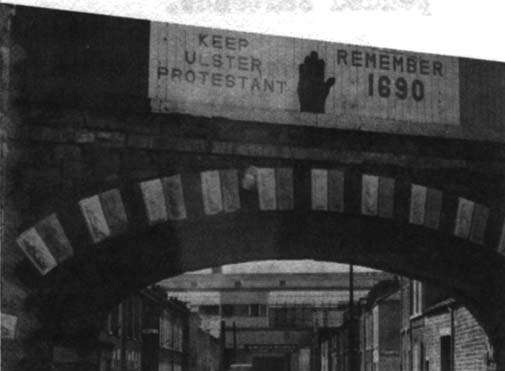

It was an astonishing suggestion from the leader of a party most of whose members seen still to believe that they must preserve perpetually what Northern Ireland’s first Prime Minister, James Craig, called a Protestant parliament in a Protestant state.

It seemed, until events overwhelmed it, potentially the most hopeful and important development in Northern Ireland’s history. Every other major reform of the last three years has been forced upon the Unionists by the British government. This time, a Unionist leader was volunteering something, and something so substantial as to imply a fundamental revision of party policies. He offered a real change, and the kind of dramatically symbolic change that might have moved people, might have been a real turning point.

But sincere or not makes little difference if no Catholic believes him, and no reform or gesture can end civil war.

The Faulkner plan was welcomed by most of the 13 non-Unionist MPs, but impact was reduced almost to nil three weeks later when 12 of them walked out of Stormont in protest against rejection of their demand for an independent inquiry into the fatal shootings by soldiers of two men in Londonderry.

Since August 9th, only a pathological optimist could see much hope for the plan.

That brings us to the other side of Mr. Faulkner’s current policy, the military side.

Now we must ask if the IRA can be crushed, if the terrorism can be stopped, and if military means can bring peace or at least force the cessation of open battling.

The immediate effect of interment was not peace but the firebomb.

By dawn on August 9, riots had exploded across Northern Ireland. Within 48 hours, 17 persons were known to have been killed and hundreds had been wounded. By the end of the week, though exhaustion had reduced the level of fighting somewhat, 25 to 30 were dead, and bomber and sniper attacks continued at a pace no less than in the weeks before internment. An effective but unannounced curfew had been imposed by the fighting; the early closing of shops, pubs and cinemas; the complete shutdown of public transport at dusk; and the fact that street lights either did not come on at all or were turned, or shot, out.

Meanwhile, at least 10,000 persons had fled from their homes. Over half of then had left the country altogether, most for Eire but several hundred for England. More than 300 of the abandoned homes were only gutted shells, sometimes fired by their owners. It was a terrible omen. How deep must be the fear and hatred of those who burn their own houses lest the “enemy” move in. And how much wider is the gap, previously often only mental but now unmistakably marked by lines of ruins, between Protestants and Catholics.

Something like those results had been widely predicted – by, among others, the British military commander when he argued that internment would only make the situation worse. Mr. Faulkner has said publicly that he was not surprised (though the Guardian reported that privately he said he was “stunned” by the fury of the reaction), and that he was satisfied because the IRA was being defeated.

Well, the price of many achievements, even peace, must sometimes be measured in blood and ruins. But many doubt that this payment is buying anything worth having.

For one thing, the effect on the IRA is not at all clear. The government concedes that it failed to nab 30%–or about 100–of the nearly 400 men on its list. Mr. Faulkner has hardly reduced doubts by claiming that one sign of success is that “gunmen were flushed out,” which seems a strange accomplishment for a policy of internment.

The general presumption – strengthened by the spectacular appearance at a press conference in Belfast of the Provisional IRA’s chief gunman – is that the net missed most of the biggest fish.

Internment had been expected, so the most wanted men were the men least likely to be sleeping at home on any night. And they may have had more than vague anticipation to guide them on the night of the raids. The IRA’s claim that there was a tip-off may be considered mere propaganda, but there had been rumors of a leak before the claim was made.

Whatever the facts may be, a still more important question is whether detaining any or all IRA leaders could reasonably be expected to work. Mr. Faulkner apparently thinks it could, because he assumes that the IRA is small, unrepresentative in both its goals and its tactics, and dependent primarily on terror for what support it has.

The last time internment was tried, during the IRA “campaign” of 1956-62, there was little reaction in the Catholic slums of Belfast or Londonderry, Strabane or Newry. But then the IRA operated almost entirely from the Republic (though that proved an unsafe haven when internment was imposed there too), and confined itself to hit-and-run raids mostly at or near the border. It was in fact less a campaign than a series of commando attacks. It had scant political impact because there was little preceding or accompanying political groundwork. There was not even much effort to involve many people in fighting; in the countryside some farmers were asked to hide people and more were asked not to notice strangers crossing their property; in some cities about the same was asked, but there was almost no action in Belfast because the southern IRA did not trust the Belfast branch.

Even two years ago, despite Unionist attempts to smear the civil rights groups, the IRA was small, isolated and impotent. Some romance still attached to its name, but not much of that survived the terrible days of August, 1969, when the IRA proved to have neither the men nor the arms to hold off the raging Protestant mobs.

Now the IRA has been rebuilt. Organization has grown out of two long years of tension and conflict in which everyone has been involved. It has been impossible not to be among the endangered in the Bogside or the Falls Road, and if the IRA ever seemed romantic or reprehensible, it now seems simply necessary. It is no longer something hazy and a little foreign, something of legend and occasional headlines. It is “our defence force.” Its strength rests on terror all right, but less on terror by the IRA than on terror of the Protestants.

General Sir Harry Tuzo, commander of British forces in Northern Ireland, said last week that probably one-quarter of Catholics must be considered “active” IRA supporters, meaning they would volunteer or willingly answer requests for aid.

That is an enormous proportion to be “active” in any sense. If it existed within a majority population it might well be sufficient to recreate the utter insecurity and constant subversion and attack that characterized Ireland in 1918-21.

A vicious circle is fully formed. Insecurity creates the need for defense. The IRA appears to meet that need, and in return it obtains support and recruits. It then has the strength for offensive actions, even ones of which some supporters disapprove (and surely many do disapprove of the bombing and shooting), because dissent is muted for fear of weakening the defenders. Whether or not Protestants and troops would otherwise stay passive, which is unlikely, the offensives bring reprisals which renew the sense of insecurity, and so it goes on.

The foregoing is, I think, true an far as it goes, but goes nowhere near far enough.

It does not indicate the depth of fear of Parents who dare not leave children at home alone while shopping or dropping in at the local pub, for fear of firebombs or shooting; or of men who go work at the shipyards never knowing when they may again be set upon and driven out by Protestant workers.

It does not describe the sense of injustice felt by those same workmen, who know that no Catholic has ever been a foreman at the shipyards; or of any Catholic who knows that in the same week a Catholic was sent to jail for six months because he had shouted, “Up the IRA” a Protestant licensed gun-dealer convicted of selling arms illegally was given a suspended sentence.

Above all, it does not begin to indicate the strength of positive commitment that opponents of the government, including the IRA, can draw on.

That commitment could be seen in Londonderry this week, when a one day general strike was 100% effective.

It can be seen in rural border areas, where Catholics turn their house lights on and off to show the position and course of army patrols which not only provides information to anyone trying to cross the border, but does so in a way that risks immediate, personal and inescapable reprisal.

In cities, the whereabouts of army or police units can be marked by groups of women who gather together and bang dustbin lids, (That is, by the way, an old tactic in Ireland, which is a point to be kept in mind when reading reports that imply that the women making the horrendous din are motivated solely by hate or think they might prevent an arrest or halt a search by noise alone.)

The commitment could be seen very clearly in Londonderry this week, when unarmed women stayed out in the open between snipers and the soldiers they were firing at. All the reports I saw implied or stated that the women had been forced to go as hostages. No one seemed to notice that the snipers must live among those women and their menfolk, and that forcing wives, daughters, sisters or sweethearts to let themselves be shot at would be political, and personal, suicide. The conclusion is necessarily that the women went willingly,

What those women did may be foolhardy, but it certainly makes nonsense of any idea that locking up a few hundred troublemakers will bring peace.

Of courses, Catholics in Northern Ireland are a minority. The IRA cannot fulfill its dream of “driving the English into the sea” (although the existence of that dream is another factor in the vicious circle). But that is to say only that armed rebellion can be prevented from succeeding, when what is needed to prevent rebellion from continuing to be endemic.

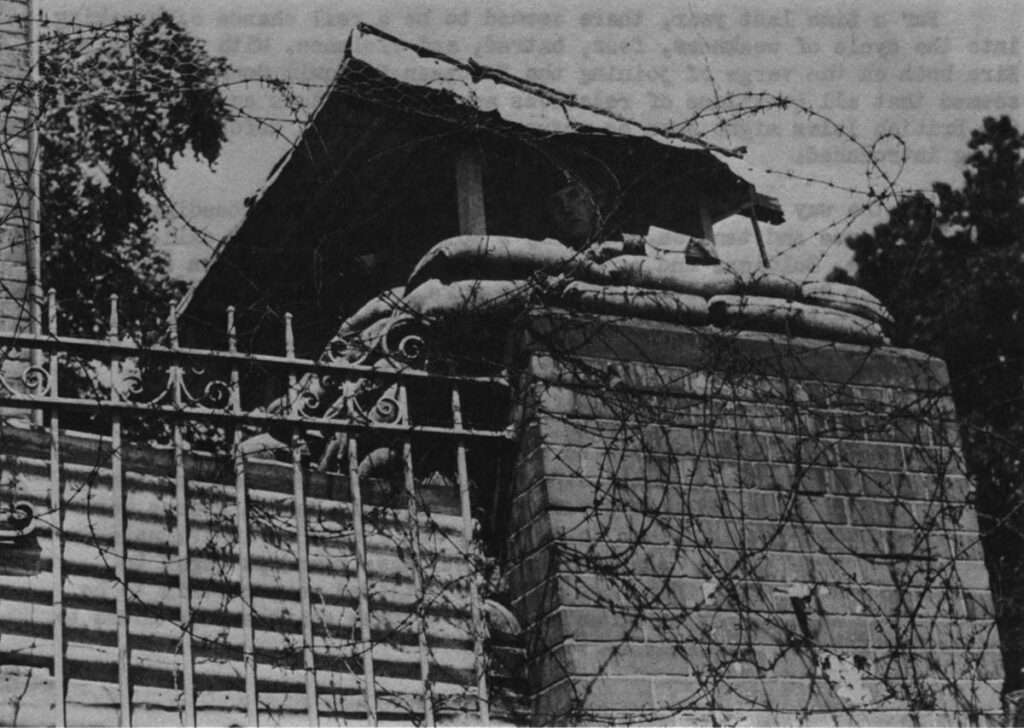

It might seen that if present methods prove insufficient, everything required for unlimited suppression is available. Besides some 3,500 regular police and 1,200 reserves, about 12,500 British soldiers and 2,500 militiamen of the Ulster Defence Regiment are on active duty. And they have enormous powers under legislation that appears to provide authority for all that the most tyrannical dictator could desire.

Belfast 1971

Civil Authorities

(Special Powers) Act

(Northern Ireland) 1922

The Special Powers Act is an extraordinary document. It begins by empowering the Minister of Home Affairs to “take all such steps and issue all such orders an may be necessary for preserving the peace and maintaining order.” He is not limited to steps detailed in the act, but may promulgate regulations himself, and they become part of the Act unless specifically rejected by Parliament.

How broad the powers are meant to be is indicated by a paragraph saying that “the ordinary course of law and avocations of life and the enjoyment of property shall be interfered with as little as may be permitted by the exigencies of the steps required to be taken under this Act.” A less effective limitation on power would be hard to imagine.

Among the powers, in addition to internment, detailed in the original Act or subsequent regulations, are:

To prohibit inquests, including inquests on persons who die in custody.

To search without warrant any person and any building or vehicle, and to seize any “firearms, ammunition, explosive substances or any document…he suspects is being used or intended to be used” to violate peace, order, or the Special Powers Act. The burden of proof is on the possessor of any seized object to show that it was not used or intended for use illegally.

To prohibit publication, distribution or possession of “any newspaper, periodical, book, circular or other printed matter.”

To arrest anyone without warrant and to hold him for 48 hours for interrogation (i.e. without the necessity of even naming the person held as is required for detention.)

To impose curfew anywhere for any length of time.

To prohibit collection or dissemination of any information about the police.

To ban any organization and to jail any members of one that has been banned.

To prohibit any assembly of three or more persons.

Belthazar Vorster, who is something of an expert in this line of business, is supposed to have said once that he would gladly trade all of South Africa’s repressive legislation for this one Act.

However, South Africa is an independent state far from any other that is strong enough or interested enough to influence its internal policies.

Northern Ireland is neither independent nor powerful. It must pay some attention to what Dublin thinks, and more to what Irish-Americans think, since the flow of money for weapons grows greatly every time strife breaks out. Most of all, Stormont must not antagonize Westminister, for nothing of which Westminister disapproves actively can be done.

Ultimately, Stormont depends as much on shifting political majorities in Britain as on the solid Protestant majority in Northern Ireland. There are limits to what British public opinion will allow, and more important limits on what it will pay for – there is already grumbling about the cost of military operations.

No one knows how wide the limits are. (It has been suggested that they are just wide enough for the worst possible result – permitting enough force to keep fear and antagonism at fever pitch, but not enough to terrorize opponents.)

In any case, true peace cannot be achieved by force alone, cannot be simply imposed on more than a third of the population. Political accommodation is needed, but making the changes that might allow it is dauntingly hard.

Some of the causes of difficulties on the Catholic side were discussed earlier, and some of the causes on the Protestant side were implied. For instance, Protestants have reason to fear the IRA and Catholic mobs; poorly-paid and unemployed Protestants are suspicious that changes might benefit Catholics at their expense; Protestants waiting for a council house do not want anyone getting in ahead of them; and Protestants with wealth or power fear that they will lose what they have to Catholics.

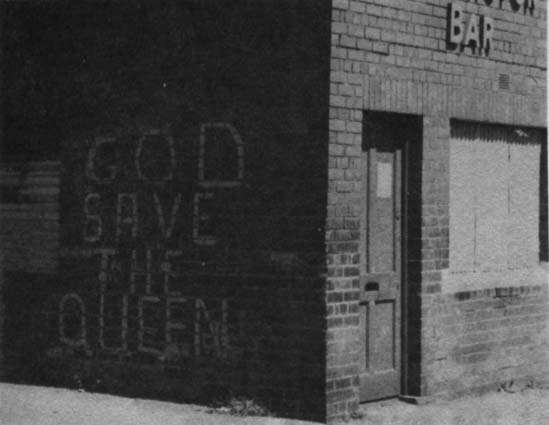

Pure bigotry is a factor as well. Catholics are said to “smell different,” and worse, of course. Catholics are sexual athletes who breed irresponsibly and expect the state to support their children. Catholics are unwilling to work but expect everything to be handed to then on a silver platter. Former Home Affairs Minister William Craig has said, “You have a lesser standard of democracy when you have a Catholic majority.” The Queens University Conservative and Unionist Association issued a pamphlet asserting that the Catholic Church has always been “subversive” (which might not be so absurd except that the context made it clear that the term meant “left-wing”).

I am not sure if there are equivalents among Catholics for all of those inanities. I do know that both groups say a person or thing “looks Protestant” or “looks Catholic” and mean precisely opposite things. And Catholics, led by the church hierarchy, have fought as hard as any Protestants against mixed marriages and integrated schooling.

(By the way, the separation of schooling is important in many Ways. Virtually all children receive training in religions that not only differ but are explicitly opposed, and learn histories in which the heroes and villains of several hundred years are exactly reversed. Moreover, Job discrimination is easy when the religion of anyone whose name does not give it away – Padraic or Brigid, not George or Victoria – is clear at once if his school was St. Something-or-other.)

In addition the economy is far from healthy. Unemployment is high and the activity rate (the proportion of the adult population working or registered as unemployed) is low. Wages are low – in 1969, the proportion earning under &16 a week was three times as high as in Great Britain. Three major fields of employment – linen production, farming, and shipbuilding – are in decline and now employ less than half of the 221,000 people employed in 1949. Attracting investment has been difficult, despite large grants, tax reductions and other concessions, because Northern Ireland is too far from most sources of materials and markets, and too often strife-torn.

Politically, Northern Ireland is a mess. It has the trappings of democracy but is actually somewhere between an old-fashioned political machine, a theocracy and anarchy.

Catholics are a minority, deprived, as described earlier, of political power even where they have local majorities. They are further weakened by internal divisions.

The well-known split between the “Official” and the “Provisional” IRA is along lines which have divided nationalists for years. The Provisionals are right-wing, like the old Nationalist Party which was known as the “Green Tories.” They want an independent, united Ireland but nothing much in the way of social change. They tend to oppose labor unions and the Labor Party or anything further left.

The Nationalist Party was closely allied with and largely dominated by the Catholic hierarchy, but the Provisionals run foul of the Church over violence.

The Officials are radical socialists, further left than the old Republican Party but like that party in at least having social and economic Policies. They are of course anathema to the church, which only recently decided it would no longer be a sin to vote for the rather moderately leftist Labor Party.

Growth of a Labor, or any other non-religious, party has been inhibited by clerical hostility, nationalism, and divergence of interest among urban, industrial wage-earners, farmers (who still formed a full 25% of the employed population in 1945, and about 12% today), and professionals. But no variety of nationalist or religious party could hope to do anything about those interests in governmental bodies where it would inevitably be an ineffective minority. Besides, nationalists who took seats to which they were elected nearly always began to lose support at once because to take the seat was seen as a “sell-out.”

Protestants, on the other hand, are the majority, have dominated politics and the economy for half a century, and appear unified. But the appearance is misleading.

A little history is needed here.

Because of different kinds of colonizing in different parts of the country, Protestants were concentrated in the north-east corner of Ireland, forming about two-thirds of the population in counties Antrim and Down and nearly half in the four other counties now part of Northern Ireland, compared with less than 10% in the rest of the country.

In the south, Protestants were characteristically landowners who rented their land. Agricultural legislation passed in London combined with growing nationalist strength to provide both carrot and stick for them to sell and depart.

In the north, many Protestants were working farmers and many of them became owners of small farms under the agricultural reform bills. They had little incentive to leave.

Furthermore, nearly all of Ireland’s heavy industry had grown up in the north, and in fact in the same two counties where Protestants predominated numerically. Consequently, there were many wage and salary earners who had no incentive to leave. And the owners of industry were offered none of the inducement or compulsion to sell that landowners faced, so they had no incentive to leave either.

So Unionism grew in the north on the basis of shared fear. But it could never be any more than anti-nationalism because it was a coalition of large landowners and small farmers, of laborers and industrialists, whose conflicting interests would destroy the coalition if ever the threat that united them were removed.

So, the threat was never allowed to disappear. Until 1969, the Unionist Party never campaigned in a general election on any platform but the threat from Eire and Roman Catholicism. Fears were not entirely manufactured of course, for there was a rebellion and then civil war in the rest of Ireland, and the IRA did campaign in the 1930s and 1950s. But every challenge to Unionist power was immediately smeared as nationalist and Catholic, and anything also that was handy – Nazism and Communism, at different times, served admirably.

The Unionist Party had no policy except to retain power. To that end, it kept the Special Powers Act in force, kept the police armed, and kept in being the half-army, half-terrorist group of B-Specials. It encouraged discrimination against Catholics in private industry, and, of course, discriminated flagrantly itself in government.

The Unionists also maintained the full apparatus of a machine through the Orange Order. Favors could be got through it; a government job, or a council house. But so could reprisals. No businessman could survive if the Order boycotted him. Enrolling more than two-thirds of adult Protestant males, the Order could make it impossible for any Protestant to decline to contribute to collections for various charitable activities or for the painting and decorating of neighborhoods that precedes the annual celebrations on July 12.

But in return., the Order acquired power over the party. No Protestant can have a political career unless he is a member. No minister can hope to enact reforms of which the Order disapproves (except, of course, under British pressure). The leadership has spent 50 years opposing accommodation with Eire or with Catholics in Northern Ireland, and eliminating from the party all who did not also oppose accommodation. Now there is no faction in the party to which a leader can appeal for support on reforms.

For a time last year, there seemed to be a real chance of breaking into the cycle of weakness, fear, hatred, and violence. With Britain and Eire both on the verge of Joining the European Economic Community, it seemed that all questions of relations among the nations and states of the British Isles might soon be changed fundamentally. Reforms were being introduced.

And the way the army was being used seemed to be succeeding in reducing violence and tension. The army’s policy was what was called a “Passive” one. Soldiers and barricades were interposed between Protestants and Catholics but made little effort to move into either group’s enclaves. Their mere presence reduced violence, and consequently fear. They also distracted some of the attention and energy of those on both sides who really wanted to fight, thereby confusing to some extent the simple hatreds on which they had been operating.

But then the army shifted to an “active” policy. It shot back more quickly and more often against snipers and firebombers. Searches for weapons and hunts for IRA men became more frequent. Men in groups were more often stopped and frisked in daytime, and groups or individuals were almost certain to be searched at night. Mass roundups began to be common, and the fact that most of those detained were certain to be released for lack of any evidence on which to base charges only added to the irritation the detainees felt.

Whatever the intention behind the change in policy, it looks now to have been a major blunder. Catholics inevitably saw it as inaugurating merely another attempt to cow and suppress them. The new policy seemed to threaten Catholics, and promise Protestants, a return to reliance on force and relaxation of pressure from London for political reforms.

The British and Northern Ireland governments have now ruled out any further reforms until peace is restored. (Mr. Faulkner has tried to soften the impact a bit by saying that all of the reforms that were promised will still occur and that his proposals of June 23 still stand and may be put into effect whenever Catholic members return to Stormont. However, he added that he considers that peace will have been restored when not only violence but all “acts of civil disobedience” have ended.)

The governments say that initiatives for reform now would appear to have been forced from them by the “blackmail “of violence, which is the rather silly reflex in which governments too often indulge, and that initiatives now would probably bring violence from Protestants – which is probably all too accurate an assessment.

I think the military alone cannot bring peace. The governments apparently think that political action cannot be undertaken until peace is restored. As vicious circles go, that’s a beaut.

British Power may prevent this house from falling. I do not think any power on earth can make it whole.

Received in New York on August 27, 1971.

©1971 Scott Keech

Mr. Keech, a free-lance writer, is an Alicia Patterson Fund award winner. This article may be published with credit to Mr. Keech and to the Alicia Patterson Fund.