Race is almost as uncomfortable a fact of life in the United Kingdom as in the United States.

In 1967 a report, Racial Discrimination in England, sponsored by P.E.P. (Political and economic Planning) provided concise, sophisticated documentation of discrimination in employment, housing and automobile insurance.

One part of the survey tested discrimination directly with teams comprising a native Englishman, a Hungarian immigrant and a West Indian immigrant. They were similar in qualifications or needs, age, height, and dress. Both immigrants spoke English fluently, though with slight but distinct accents. In each test, the West Indian went first, then the Hungarian, and finally the Englishman, and none knew of the others’ experiences until after the test ended. The results were striking.

EMPLOYMENT: The West Indian was discriminated against in 90% the Hungarian in 43%, of the places where the Englishman found a positive response.

HOUSING: After excluding places advertising “No Colored” and the like, the West Indian was refused two-thirds, the Hungarian 6%, of the places open to the Englishman.

INSURANCE: Where the Englishman was offered insurance at a certain rate, the West Indian was flatly refused 30% of the time and quoted higher rates another 55%. The Hungarian was never rejected but was quoted higher rates (though lower than the West Indian’s) exactly half the time.

So well known are the facts that relatively little was said about intentional discrimination at the Fifth Annual Race Relations Conference in London, September 23-24. More was said about some of the effects of some non-racial policies and even of policies intended to counter racial discrimination.

Thus, segregation in housing results in part from factors outside the control of housing authorities. For example, discrimination in employment plus the lower skill levels of many immigrants leave them with lower incomes and hence less choice in housing.

Residency requirements for council housing are within local authorities’ control, and may unintentionally exclude recent immigrants – where demand is terrifically high, even something as blatant as Wolverhampton’s ten-year waiting period may not be only racist. In any case, changing such rules fairly is obviously extraordinarily difficult.

Housing authorities also face the dilemma that policies intended to reduce racial separation may come a-cropper on individuals’ desires to maintain communities of kin, friends and cultural contacts; while building for separate groups may prevent moving by those who would like to move. Meantime, trying to enact a policy that allows both choices may crash once more into outside barriers – how much choice can a man really have on an income of 15 pounds a week?

John Lambert and Camilla Filkin, from whom many of these points are taken, went further. Research exposing such dilemmas may be ignored by policy makers who want simple, neat programs. It may be attacked if it reaches some such conclusion as that the problem is less a matter of races than of failure to provide enough housing for anyone. Attacks may be strenuous indeed, and funding and access to records may be denied, if the researchers decide that the failure in housing is symptomatic of the more general failure of the whole system to provide a decent life for all.

Imagine the response of someone who thinks he has a tough problem and is told he actually has a different one, and a tougher one at that. If he already has a pretty good idea what he wants to do, especially if he thinks he is prepared for the moral and politically risky thing, the reaction may be explosive.

Other sorts of problem were discovered in journalism.

The media “made a real effort to give a balanced, factual account of… disorders,” but tended to exaggerate “both mood and event.” They have failed “to report adequately on… the underlying problems of race relations” or “to communicate…a sense of the problems…and the sources of potential solutions.” They have not communicated appreciation of what it is like to be black or of black history and culture. “When the white press does refer to Negroes…it frequently does so as if Negroes were not part of the audience.” One cause of these failures is the small number of black reporters, and the smaller number of black editors.

These were conclusions of the Kerner Commission, but they might have been stated by Paul Hartmann and Charles Husband in their report on the British press. They reached two conclusions.

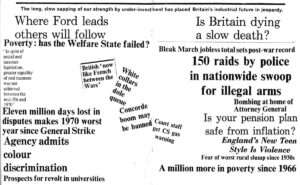

First, the media tend to express uncritically the prejudices of the society at large. They found some horrendous examples: the lengthy front-page reports in March that births among immigrants had risen in the preceding quarter, compared with the short inside-page reports three months later that births dropped, and new immigration plummeted, in the next quarter. Then there were headlines: for example, “Immigrants found in black hole,” and “Indians invade,” both of which were among the scare heads and perfervid coverage given to the discovery of 40 illegal immigrants in July.

Second, the normal processes of the news media, prejudices aside, are sources of problems. To paraphrase very freely, every journalist knows that dog bites man may not be great stuff, but no bite is no news at all. The trouble is that in selecting conflict for coverage, the press reinforces, and sometimes creates, the impression that conflict is the main characteristic of relations between blacks and whites.

Then too, the best news and the best reporting, for editors, is unambiguous yet evocative of deep, widely-held feelings – the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor was, in this sense, a perfect story. And, after December 7, 1941, “Pearl Harbor” became shorthand for sneakiness, for a threat to America, and so on, and can be used in all sorts of contexts.

Similarly, “Watts” has become shorthand in both the United States and the United Kingdom for riot, fighting between blacks and whites, threats to whites’ lives (never-mind that nearly all the dead were black), destruction of whites’ property, and so on. That the images may be wildly inappropriate is likely to be overlooked or disregarded in the rush to deadline. The result is to worsen race relations.

The researchers found that most of the media assumed unquestioningly that immigration and births to immigrants are problems in themselves, and also assumed that in general the relationship between blacks and whites was one of conflict. They found these presumptions shared by children they interviewed, but they found the highest expectations of violence among children outside the areas of high immigration.

That, they concluded, had to be blamed to some degree on the media, not only because of prejudice, but because of dealing with racial matters as “just another story.”

Another discussion that would have sounded familiar to Americans was on the police.

(By the way, the references to America are neither gratuitous nor parochial. The American experience is very much on people’s minds here. It is an obvious reference to make, providing the horrible example for both those who want strong action to end discrimination before that nadir is reached, and those who think the races must fight unless immigration is ended and repatriation started. Also, American research has provided questions for British social scientists, and they keep finding depressingly similar answers.)

The panel, called Conflict and Race in the Community, was somewhat disjointed. The first speaker was Dick Blackett, who outlined the views and program of the U.S. Black Panther Party. The third was Ashraf Ali whose main contribution, and no small one, was to note that he had been asked to substitute for a Pakistani, that despite his name and Islamic religion he was not Pakistani but Trinidadian, and that the event and the program of the Black Panthers showed once again that too many people lump all the immigrants together. As the old joke has it, all Americans look alike. He seemed a gentle man, more sad than outraged, with still some hope for reform.

In between came Reg Gale, chairman of the 90,000-member Police Federation, who was milder than he sometimes has been, and a good deal milder than his Federation’s magazine. His presentation went like this:

The colored immigrants live in slums and feel mistreated, which creates friction. The police are understaffed and under trained. An officer in a white neighborhood knows from his own experience how civilians see him, and what to expect from them; neither is true in immigrant areas. Most of the police in immigrant areas are young and new, still learning their jobs, and they make mistakes, which creates more friction.

Some policemen start prejudiced, but most don’t. They don’t mind being called “pig” because they get used to all sorts of names. When they arrest drunks on Saturday night, they hear abuse, but it does not mean anything special and everyone forgets it. Not so with immigrants, who believe they are singled out and who often bring hostility toward police with them from their homelands. The continuous hostility “can create prejudice” where there was none.

Finally, the police are in an impossible situation, called on to deal with situations they often cannot understand let alone resolve, where anything they do is likely to dissatisfy someone. Basically, the causes of problems lie elsewhere – especially with politicians who do not live in their constituencies and try to “legislate against social problems.” But in the event of “an eruption, it is our heads which are going to get cracked.”

He didn’t get much sympathy. He was attacked fairly strongly for allegedly glossing over the extent to which police do single out non whites and harass and abuse them. He replied that even conceding prejudice – he would not concede anything else – the major problems are caused and must be solved elsewhere.

What emerged from the discussions was that combating racism is not only a matter of preventing active discrimination, nor even a matter of new departures – of, say, independent police review boards. Rather, it requires changing or eliminating practices that may have grown up entirely without reference to race.

For example, proposing “community control of police” runs counter to a long, hard-fought battle to make police independent professionals, outsiders in a sense, to prevent them from discriminating because of their own or their employers’ likes and dislikes. Such a proposal is not for reform or extension of existing practices and powers. It calls for people to reverse themselves, which is of course the hardest kind of change.

It is still harder when what is attacked has acquired the status of an ideal—independent police, free press, or whatever. It is harder yet if the ideal is something of a shuck.

Forced to think about it, most people know that the independent, impartial police, or courts, are very often no such thing. Rich and poor are seldom treated alike, whether stopped for speeding or arrested for murder.

The differential treatment does not occur in a vacuum. Baldly stated, the rich make the laws that define what crime is – most obviously in the case of property, but perhaps more importantly in the case of those, like disturbing the peace or public nuisance or vagrancy, that tend to define the limits of “polite” behavior. The same people make the other kinds of laws, such as those allocating government funds to public housing and consequently defining what the housing program will be.

There is less tendency here than in the U.S. to see economic and political power as separate things, and much more tendency to assume that society is divided into true classes. That is, “class” does not refer, as it often does in the U.S., just to different income levels. It means, at least, that society is made up of two basic groups, one of which has economic and, therefore, political power; and that their interests are inevitably in conflict because one class can get or keep power only at the expense of the other. One implication is that the ideals of police or journalists or housing officials are largely imposed by and for the upper class. They are, for the lower class a shuck.

Most of the speakers at the Race Relations Conference assumed or concluded that class divisions are of major importance in industrialized societies (not necessarily only capitalist ones). That raised questions about the cause(s) and development of racial and ethnic discrimination.

Sami Zubaidi of Birkbeck College argued that race relations “are variants of general class relationships.” In England specifically, the situation “can best be understood in terms of the systems of production and distribution, and the related political systems of advanced capitalist societies.”

The gist appeared to be that racial discrimination is an extreme form of the economic and political exploitation usually practiced by those in power against all those not part of their class. Color only makes the distinction more obvious to the upper class and its agents.

Anthony de Reuck of University College, London, argued that members of communities recognize those who belong and those who do not “by means of physical cues (e.g., colour) or cultural cues (e.g., language or religion). Objective genetic differences become…culturally defined as ‘racially’ significant. Similarly, certain cultural differences, even in the absence of genetic differentia, may also become defined as significant for an allegedly ‘racial’ conflict (for example, Eta in Japan.)”

Here the gist seemed to be that strangers are enemies, at least potentially, and do not in any case have a right to the same treatment as friends. The greater the strangeness, the greater the fear and hostility.

Presumably, in both theories, conflict is greatest when class and racial or ethnic lines coincide, and reduced when there is some crossing of lines.

(Both theories are oversimplified and overstated to make the contrast. There are various in-between views and combinations. There is also a view which did not happen to be expressed at the conference, though it was implicit in some statements. That is, that neither class, racial nor ethnic distinctions must always mean conflict and violence. It may have been implicit because most people accepted it.)

Pierre van den Berghe of the University of Washington took a different view, but I’m not sure I understood it completely. He argued that “relatively few societies”—only about 20, in fact—have considered innate physical distinctions important for purposes of social stratification. As for ethnic distinctions, some societies are multi-lingual and/or multi-religious without conflict or stratification on ethnic lines.

Every society must recognize ethnic distinctions, because large differences in language or other aspects of culture are inescapable. Consequently, many societies are multi-ethnic. But only a few consider physical distinctions socially important, so only those few are multi-racial.

In every one of them, he says, racial stratification is “steep.” Furthermore, every one of them introduced the concept of race as “an additional basis of invidious distinctions, of political oppression and economic exploitation.” Hence, “race is intrinsically invidious” and, therefore, all multi-racial societies are racist.

Ethnically different groups may live together in peace, but the “only way to eliminate conflict from race relations is to eliminate racial distinctions themselves.”

Race exists “where it pays.” In Spanish America it stopped paying after Spain lost control, partly because the racial classification scheme became so elaborate no one could remember all of it, and racism is only vestigial in Peru and Mexico.

Granting the assumptions about race and ethnicity, it remains unclear to me that ethnic discrimination is less invidious or easier to eliminate once it has begun. Still, the idea that the idea of races is racist has a certain shock effect that may be valuable.

As some questioners noted, Professor van den Berghe offered nothing in the way of a program for eliminating racial distinctions. No one seemed to notice the time scale implied; an end as far in the future as Spain’s withdrawal from America is in the past is only preferable to no end at all. On the other hand, that implication was as close as any speaker came to dealing with the question of how long any resolution might take.

Received in New York on October 6, 1970.

Sept. 28 1970

12 Southwell Gardens

London., SW 7

©1970 Scott Keech

Scott Keech, a free-lance writer, is an Alicia Patterson Fund award winner. This article may be published with credit to Mr. Keech and the Alicia Patterson Fund.