Dec. 13, 1970

Except for signposts, there is no obvious indication that the border between England and Scotland has been crossed. Countryside, roads, buildings and towns look the same. Even Edinburgh, the capital of Scotland, does not feel noticeably Scottish. There are plaids and tweeds and lots of woolen goods in shop windows, the Scottish flag flies, the museums display Scottish memorabilia, and the postboxes are labeled “ER” not “E II R” because only one Queen Elizabeth has reigned over the Scots. But walking around the city brings no surprises, no feeling that this or that is especially Scottish.

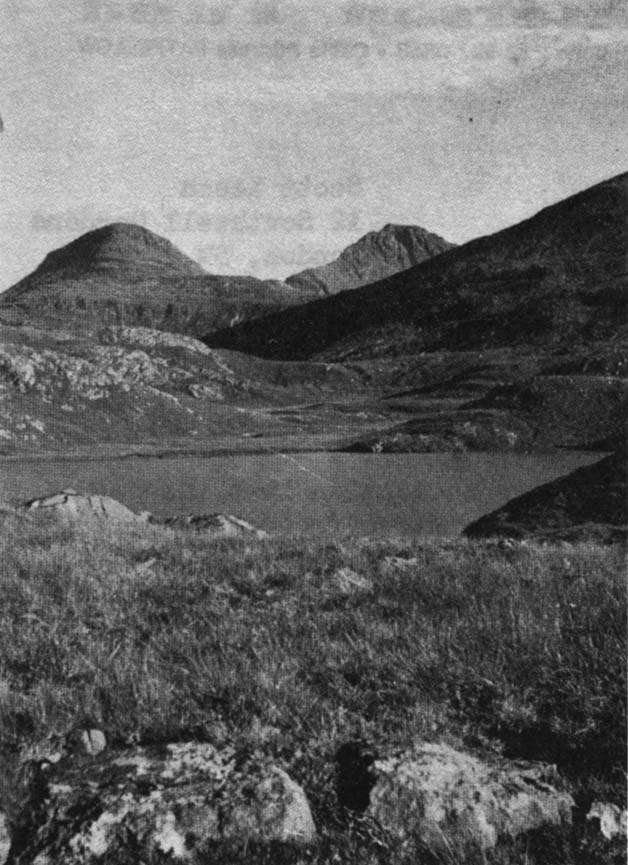

Driving on to the north, beyond Perth, the Highlands begin, and so does a feeling that this indeed is different. The scenery is as spectacular as the tourist brochures claim, but that is not the cause: “green and pleasant land” has long since proved a wholly inadequate description of the startling contrasts and sometimes wild beauties of British scenery.

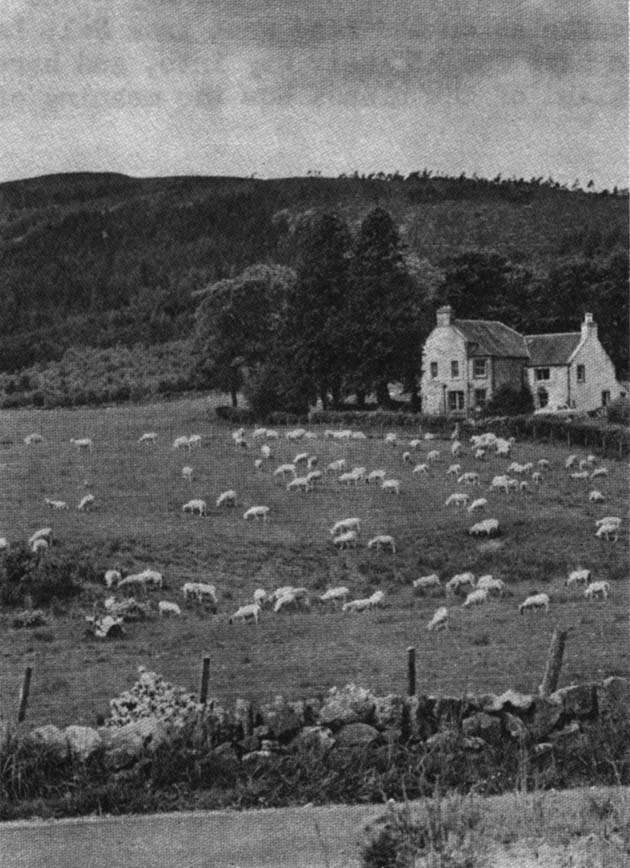

But mile after mile it was scenery and sheep, sheep and scenery – and no people. Houses and towns seemed as scarce as on the road west from Salt Lake City, but there it is desert that people have fought their way into, and here is a land where people once lived – the land of the clans. Now the meaning of the Clearances took on a new dimension.

The battle of Culloden in 1746 is a great landmark in Scottish history. It ended for ever the hopes of the House of Stuart. It was also the battle that marked the end of the clans.

For long, Scotland had been almost evenly divided between the Highlands and the Lowlands in population and in power. The Lowlands were richer, but the Highlands had men at a time when it was the quantity and quality of men that won battles. But power had been slowly shifting, as the Lowlands became still richer, as cannons became more mobile and more devastating, and as even the balance of population moved south.

In the last Stuart rising of 1745-46, Prince Charles was supported almost solely by Highlanders. When the rebellion was put down, the British government took the opportunity to eradicate what it considered a dangerous force. (Support for the Stuarts in general, and “The Forty-five” in particular, looked more threatening to contemporaries than they have to historians. Since the Union in 1707 there had been three other risings, in 1708, 1715 and 1719, though even to contemporaries only “The Fifteen” had looked very serious. And the clans were the more feared and detested by the English for their alliance with the French in numerous past wars.)

Culloden was itself a disaster for the clans. Of about 2,000 men in the Prince’s force, perhaps 1,200 were killed and 300 were captured. In the following months the British Army occupied the Highlands, hunting rebels, burning the homes of suspects, and disarming the clansmen. At one time, some 3,400 persons were imprisoned as rebels, of whom 900 died (120 by hanging, the rest of wounds and disease) and 1,150 were banished or transported to the colonies.

During this period, the Army lived off the land, which was destructive enough, but also, as a matter of policy, the clans’ main means of living was destroyed, for their cattle were confiscated and auctioned off.

In 1747, the kilt and plaid were banned, and the hereditary jurisdictions of the chiefs were abolished.

The jurisdictions were crucial, for they had made the chiefs absolute rulers. The plaids did not signify as much as later romance has pretended (Another illusion down the drain!), but kilt and plaid did distinguish Highlanders from everyone else. It is a measure of how quickly and completely the power of the clans was destroyed that the ban lasted only 45 years, and when it was lifted there was apparently no reaction at all.

Meanwhile, the economies of England and southern Scotland were growing more similar and had begun the expansion that would soon lead to the Industrial Revolution. A major reason Prince Charles had found so little support in the Lowlands was that trade was booming. It was no doubt uneven, although not nearly so much as after industrialization, but the evidence is strong that total national income and real wages rose substantially during the l8th century.

England may have benefited most, but there was certainly money being made in Lowland Scotland, as two examples may show: Expensive improvements on the harbor at Greenock on the Clyde estuary were begun in 1710 were fully paid for by 1740; Glasgow merchants owned 67 ships in 1735 and 386 ships in 1776.

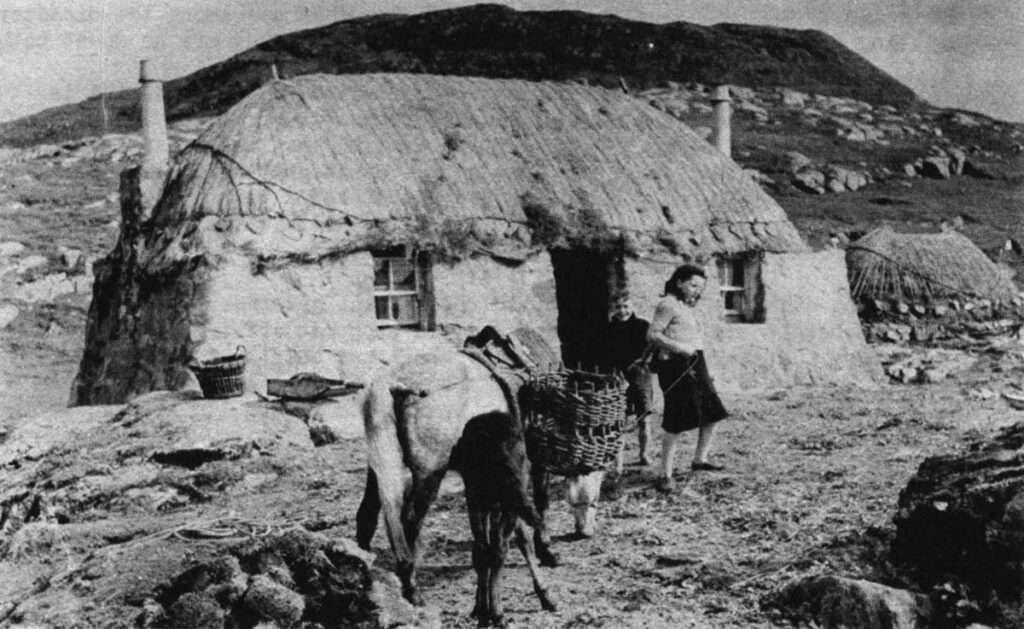

After 1745, partly for military reasons in the Highlands, partly for trade reasons, hundreds of miles of roads were built in and between Scotland and England. The roads helped expand the market economy, and if the crofters-tenants-still lived mostly on subsistence agriculture, they had more and more to find ways to pay rents in cash rather than in kind or service as before.

In the 1780s, sheep came, and throve. Soon they began to displace people. In 1785, the Clearances began in Glengarry.

What happened was that crofters’ leases were simply not renewed. What resulted was that home, livelihood and community were destroyed at a stroke.

As sheep and clearances proved successful, they spread. in 1807, the “Great Clearances” began, in Sutherland.

The Marquess of Stafford was the greatest landowner in Britain with around a million acres altogether, including some 370,000 acres acquired by marriage to the Countess of Sutherland. He was one of the great landowners known as “improvers” – those aware of the most modern methods and crops, and determined to make farming profitable. But no amount of improvement would make family farms in the Highlands as profitable as sheep-walks (or, as some owners found, as reserves to be rented to hunters).

In his way, Stafford tried to be humane. Before beginning to clear his land, he established certain coastal industries, particularly processing of kelp. But they soon failed, and in any case they could not have begun to absorb the 5,000 people removed from Sutherland alone (and replaced by 200,000 sheep) in the next thirteen years, Still less could they absorb the further thousands removed from other lands in those same years.

With each year, the Clearances became more brutal. Here and there, people resisted and after resistance, or to forestall it, the sheriffs’ men moved quickly. It became common for a tenant to be served with a writ of deforcement, to be ordered out at once and, at the end of an hour, to see his cottage and any goods still in it burned. Pregnant women, the old and the sick, all would be removed in the same way. There are tales, some with supporting evidence, of homes set afire with people still in them.

There was the casual brutality that the minions of the powerful are likely to inflict on the powerless. And there was the brutality that resulted from the sheer size of the removals. Ten or a hundred wretches may excite sympathy and find assistance; thousands do not. A few dozen homeless may find new homes with relatives, but what if they are, like a most un-comic version of Chief White Halfoat in Catch-22, surrounded by land that is also being cleared?

The Clearances went on until 1820, all but halted for 20 years, then swept on again until 1854. No one will ever know how many people were removed or what happened to all of them, but in one four-year period before the Great Clearances began, 1800-1803, 5,000 people emigrated in ships sailing from Highland ports alone.

Not all the depopulation of the Highlands was directly by clearance. In 1832, cholera was epidemic. In 1836, crops failed and there was famine. In 1846 and 1847, the potato blight came and, as in Ireland though on a smaller scale, people starved not because there was no food, but because other crops were exported as usual.

The Clearances did excite concern elsewhere, but not very much. A Parliamentary Committee of Inquiry concluded in 1841 that there was an “excess of population” of 45,000 to 80,000 of the total of about 400,000 in the Highlands. Emigration was therefore encouraged, and sometimes forced – poor relief might be denied, and newly removed tenants would be presented with the choice of starving or of emigrating on the ships that were standing by.

It is hard to express and probably impossible to exaggerate the enormity of human suffering the Clearances caused, But those who have, to their credit, responded to the suffering have sometimes gone on from condemning the Clearances to romanticizing the Highlanders, from pitying the clansmen to elevating them and their culture into something especially fine and noble.

It is important to distinguish between the Clearances and the destruction of the clans. The former was horrible, not just by latter-day standards but by the proclaimed morality of the time. The latter need not have been so brutal perhaps, but was probably inevitable, and what was lost was by no means entirely desirable or admirable.

Highlanders were not all honorable, brave, strong and free, any more than most other people are. And for most of them, life was short and hard, often desperately hard, for they were poor and very much at the mercy of their chiefs. They went raiding or to war so readily because the prospect of booty was attractive and because a man who refused would be turned out of his home. Then he would starve, or turn bandit, or emigrate if he could, because no other clan could or would take him in.

The effects of events in the Highlands were complex, but a couple may be noted here.

Before the Clearances there were two societies in Scotland, with different economies, political forms and cultures. Each was powerful enough relative to the other that conflict between them was a serious matter, and they were inevitably in conflict because the interests of each could increasingly be furthered only at the expense of the other. By 1745 they could not even get together against the English, where before each had at least been for the other “the enemy of my enemy.”

After the Clearances, the competition was ended, and sheer difference between Highland and Lowland life was no longer a sign of danger. That also meant a reduction in the perception of difference, or a change in attitude about it: it is a very human tendency to appreciate or romanticize the life and values of a fallen foe.

Thus, it is only after and, it seems, because of the destruction of Highland power that the clan and the chief, the kilt and the plaid, and the Clearances themselves, could take their places along with Wallace, Bruce, the Stuarts and others in the history and legends of all Scotland and all the Scottish. (This is not to say that events mean the same thing to everyone. To socialists, the Clearances are a particularly raw example of exploitation by the upper class. To nationalists, they am among the disasters resulting from the Union. To socialist nationalists, they are no doubt both.)

Yet the Highlands remain a distinctive region of Scotland. (It is possible to argue that the region is itself a number of regions. For example, the long history of occupation by and trade with Scandinavia has left the Orkney Islands and Zetland – the Shetlands – noticeably different in dialect and culture from the rest. That is a useful debater’s point against the nationalists, but otherwise seems too fine a subdivision to worry about in present circumstances.)

In no other area of Britain has the central government been for so long so directly and explicitly involved in economic affairs. Since the disaster of the early 19th century, the wheel has come full circle. The crofters have by law a security of tenure that is unique in Britain. And the most recent government development agency summarizes its activities as “Project Counterdrift” – an effort to halt depopulation, and achieve repopulation, by improving the “economic and social conditions” of the Highlands.

The Highlands and Islands Development Board, set up in 1965, was the first of the Labor government’s regional development boards and is still unique in the range of its powers. It can spend up to $120,000 on a project without approval from higher up. It can give grants or loans to businesses for building or expanding plants. It can build “advance factories” for sale or lease to businesses. It can acquire land. It can go into business itself by becoming a full partner in equity in a new business.

When the HIDB was set up, the population of the Highlands was dropping by about 1,000 a year. Unemployment was over four times the UK average, while per capita income was under two-thirds of the UK average.

Dealing with the situation was made more difficult by sizes, at both extremes. The seven northwestern counties of the Highlands and Islands cover some 14,000 square miles (47% of Scotland and 15% of the whole UK) but have a population of 275,000 (5% of Scotland’s and less than half of one per cent of the entire UK’s).

So, the HIDB is involved in a large number of projects, most of them small. By March, 1970, it had disbursed about $15 million on 1,200 separate projects expected to create a total of 4,400 jobs.

The range of projects is very wide. The Board helped bring a precision optical plant to Barra in the Outer Hebrides, a computer component factory to Kingussie in the Grampian Mountains, a computer center to Inverness. It is subsidizing the modernization of a coal mine that has been worked at Brora for 500 years. It lobbied for the huge aluminum smelter being built at Invergordon on the Moray Firth. It cooperates with other bodies on agriculture and forestry. It has subsidized the purchase of about 100 new or used fishing boats (of 300 at Highland ports) and of fish processing facilities. It supports development of tourism, and lobbies for better rail, road and air communications within and to the region.

The Board has its critics, naturally. It has not always been as sensitive as it might have been to people’s desire for consultation and participation in projects, particularly ones with large effects like the industrial estate at Invergordon. Setting up individual owners of fishing boats may prove less than kind if competition from the Scandinavian factory boats increases. The Board may need to be more concerned with the human and environmental effects of major developments.

Sometimes the Board is undercut by other agencies. For example, rail lines continue to be shut while alternative transportation is lacking. This can be galling when, as in a case now under consideration, the deficit of the line is a small fraction of what it costs a development agency to create the number of jobs that will be eliminated by the closure.

The Board believes it has achieved solid results. The unemployment rate is as high as in 1965, but that it is no higher is an achievement since the UK rate has more than doubled. Net emigration is thought to have been halted. Besides the 4,000 or so jobs created directly, the HIDB believes it has indirectly saved jobs or brought new employment for 6-8,000 people.

Overall, the Board believes it has “turned around” the Highlands, making residents and those who make investment decisions think of the area as one with the potential for an attractive future. Certainly, the development around the smelter and other projects may be expected to have a lasting impact. But there are other signs that, although only the impressions of a single traveler, are interesting.

After the oppressive vacancy of the land, Inverness, with 33,000 people, may feel larger than it is. But there is no mistaking the atmosphere of bustling energy, and the new buildings – and traffic jams are more persuasive than statistics as evidence that the “Capital of the Highlands” is booming.

There are one main road and one rail line from Edinburgh to Inverness, and for most of the way they run parallel and often within a few hundred yards of each other. The little towns along the way all cater for tourists but at two there are rather spectacular developments.

One is at Aviemore, where an enormous sports center has been built in the apparently well-founded expectation that summer tourists and winter skiers will be ever more numerous in the years ahead.

The other, and most interesting of all, is “Landmark” – the name alone bespeaks tremendous pride and confidence. This is a brand-new conference center plunked down in the heart of the Highlands. It should in fact be a great success, and not only because the number of tourists has been increasing at the rate of 12 to 15% a year. Businessmen, academics, or what have you, ought to find the combination of scenery, sports, isolation and conveniences irresistible. But whoever dreamed it up was imaginative indeed.

Note: The discussion above of the destruction of the clans lacks the heat of the events. For that a book by John Prebble, The Highland Clearances, is recommended. It is passionate, partisan and, except for occasionally overjuicy prose, altogether excellent.

Received in New York on December 18, 1970.

12 Southwell Gardens

London, SW 7

©1970 Scott Keech

Scott Keech, a free-lance writer, is an Alicia Patterson Fund award winner. This article may be published with credit to Mr. Keech and the Alicia Patterson Fund.