Jan. 8, 1971

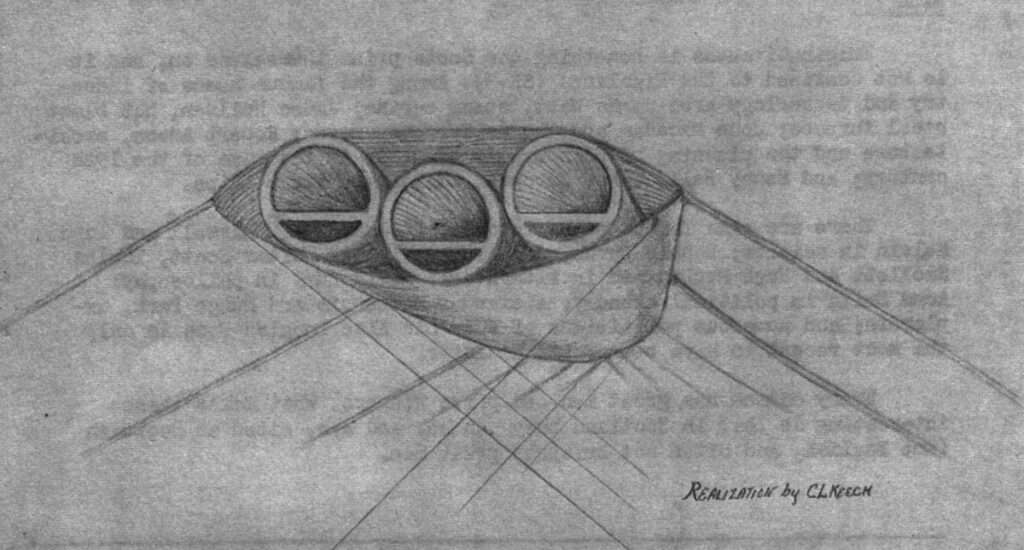

In ancient days, Scylla and Charybis terrorized Ulysses and other mariners in the Strait of Messina, and their home is still something of a menace today. When the Italian government sponsored a design competition for a road and rail link between Sicily and the mainland, entrants had to take account of the strong winds and currents in the Strait, the earthquakes common in the area, and the necessity of leaving space for ships to pass.

Most of the entries were more or less ordinary bridges or tunnels, but unusually expensive because of the special conditions. But one entry met all the conditions, and was unusually cheap besides. That one is a “submarine bridge” or “floating tunnel” – two tubes for roads and one for a railway inside a flotation envelope, the whole to be anchored 250 feet under water. The design was submitted by a consortium headed by a Scottish firm.

Imaginativeness is something the Scots pride themselves on, and it is not confined to the Highlands (SK3). Among the famous names of industry and technology are: James Watt, steam engine; James Neilsen, hot blast steel furnace; John Macadam and Thomas Telford, roads; Robert Adams, architecture and the planning of Edinburgh’s New Town at the turn of the l9th century; and Henry Bell, first European builder of steam ships.

There are also famous names in other fields: Clerk Maxwell and Lord Kelvin in science; Bobbie Burns, James Boswell, Sir Walter Scott, Tobias Smollett and Hugh MacDiarmid in literature; David Hume in philosophy; Adam Smith in political economy; Alexander Mackenzie and Mungo Park, explorers; and numerous politicians of whom Sir Alec Douglas-Home is only the most recent to have been Prime Minister.

Every nation has great men and prize winners. What makes these interesting is that in Scotland they can be, and are, cited as Scottish (not English, and often not British) great men.

Another very Scottish, very imaginative group is the Scottish Council (Development & Industry). It was formed in 1946 by the merger of a council on development (founded 1931) and one on industry (1942), hence the name. It describes itself as “an independent, nonpolitical organization, financed voluntarily by Local Authorities, Companies, Banks, Chambers of Commerce, Trade Unions and other corporate bodies, as well as by private individuals, all of whom are represented on the Executive Committee….”

Basically, the Council attempts to attract industry to Scotland, and to increase exports of Scottish goods. It is especially concerned to attract businesses using the most modern techniques in the most modern fields, and it places great emphasis on research and development and on information processing.

Those concerns are not narrowly defined, Having concluded that the “movement of ideas and meetings of people” are as important for an economy as transportation of goods, the Council is interested in data links, picture phones, film, television and radio, and publications of all sorts, as well as air, rail, road and sea communications. It sponsors trade fairs to attract investment and capture foreign markets. The Council also sponsors conferences; last November it began a series of biannual International Forums on Change and Development.

In addition, the Council carries out, or sponsors, and publishes its own studies, and it is in them that imaginativeness is most striking.

In February, 1970, the Council published a “development strategy” for the next 30 Years, concentrating on central Scotland. Approximately four million people, about three-quarters of Scotland’s population, live in the 11 counties of the central belt which includes Glasgow and Edinburgh.

The area has numerous problems, but the most serious are posed by the constant threat to prosperity resulting from the continuing decline of the heavy industries of mining, metal manufacturing, and the shipbuilding and related heavy engineering of the Clydeside. Taking the last as an example: In 1959, more than 22,000 men were employed on the Clyde, and they produced about one-twentieth of the world total of shipping. In 1969, fewer than 16,000 men were employed, and they produced only about one-sixtieth of the world total.

There are various ways to approach such large problems. The Scottish Council has chosen to propose a comprehensive scheme, some of which reads like the Pioneering-technical science fiction of Robert Heinlein’s early books.

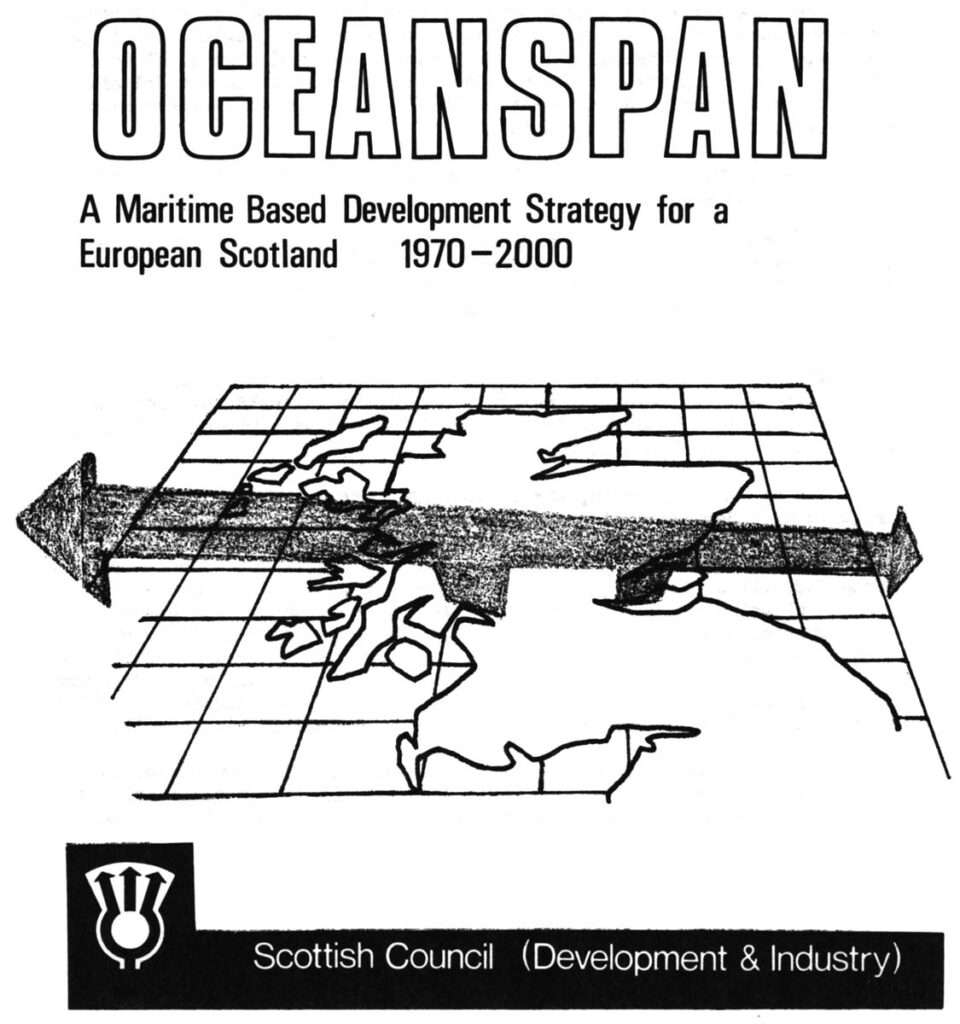

The study is called: “Oceanspan – A Maritime Based Development Strategy for a European Scotland, 1970-2000.”

The point of departure is the conclusion that sea transport will be increasingly important to handle expanding world trade, and that ships will get bigger and bigger.

In 1948, the largest tanker in service was a 26,000-tonner. Today, a 326,000-ton tanker is at sea, larger ones are being built, and tankers of up to a full million tons are on the drawing boards and are likely to be built soon.

But not only the tankers are giants. Bulk carriers of 100,000 tons for iron and other ores are already in operation and bigger ones are coming. Container ships of similar sizes for mixed cargoes will not be far behind.

The reason is simple: Capital and running costs of a 500,000-ton ship are about half as high per ton as for a 50,000-ton ship.

That’s a reason that amounts to a compulsion, so the trend Will continue. And there may soon be new developments – for instance, huge submarine tankers to bring oil under the ice from the Arctic to Europe.

The development of enormous ships brings enormous problems, especially for ports. Few terminals are capable of handling vessels of over 100,000 tons. Fewer still have safe approaches and sheltered anchorage’s for them. A 100,000-ton ship is about 800 feet long and draws 60 feet of water. For a ship of 500,000 tons, the respective figures are 1,400 and 120 feet; for one of a million tons, they are 1,800 and 150 feet.

The length of these ships creates relative difficulties, for they need immense spaces for maneuvering. The recent collision of the Allegro and Pacific Glory was probably caused fundamentally by the lack of room in the English Channel – and they are, by comparison with What the future holds, only small tankers. The draft of such large vessels creates absolute difficulties, for they would simply go aground in the Channel or anywhere along the coast of Europe from Cherbourg to the Skagerrak.

Scotland, however, has deep, sheltered waters with safe access on its western coast, and it lies on the Great Circle Route, the shortest path between Europe and North America. Shipyards capable of building and servicing the largest craft, and a dry-dock capable of conversion to handle ships of up to a million tons, already exist on and near the Clyde estuary. Flat land is available for the construction of docks and storage, transport and manufacturing facilities above or below ground.

Furthermore, Scotland has a narrow waist with the ports on the Firth of Clyde separated by less than 75 miles from those of the Firth of Forth. All the markets of Europe are readily accessible from the east coast. And finally, the central belt is already a “conversion economy” – one which imports material to produce and export finished or semi-finished goods.

“Oceanspan” is intended to take advantage of the fact that Scotland “lies like an off-shore platform strategically placed between the Atlantic Ocean and Europe.” Trade, which has for many years been oriented north and south, should be reoriented east and west, and ports and factories should be developed to create “an industrial corridor in Central Scotland, fed by an ocean terminal in the West and supplying Europe through a distribution terminal in the East.”

In the end, Scotland would be “Europe’s bridgehead” and its industrial belt would be the “key span” between Europe and much of the rest of the world.

The idea may sound like a prescription for a 75–mile-long factory, but it is not that mechanistic or simplistic. The planners are aware of people’s needs and that the issue for the future is not “what people will accept in the way of living and working conditions, but what they actually aspire to.” The study includes recommendations on preventing pollution, providing recreation areas, preserving space to be seen and felt, and relieving housing and traffic congestion (around Glasgow, the situation is almost exactly the reverse of that in the Highlands; 48% of Scotland’s people live on 5% of the land).

The strategy is also an attempt to meet the rational fears of change, which devalues old skills and threatens livelihoods and status, yet to prevent delaying the decisions – which are needed to control change. It is a strategy of flexibility, in which objectives are outlined as a model against which to test specific development proposals, not a program determining where every factory and house must go.

Whatever may be thought of the proposals, it should be noted that they are influential.

On December 30, 1970, the Clydeport Authority issued a report on development plans which the Edinburgh newspaper The Scotsman headlined: “10-year plan for Clyde ports is move toward Oceanspan concept.” The editors evidently think the concept is well known to their readers, for the story included only a single sentence of explanation.

Also, while the Scottish Council is imaginative, it is very much a part of the establishment. It calls itself “nonpolitical” but “non-partisan” would be more accurate, for it sometimes acts as a pressure group and it has very strong links to government.

One of its components, the Council on Industry, was largely the creation of a Secretary of State for Scotland – that is, a member of the cabinet in the government of the United Kingdom – who felt the lack of an equivalent for Scotland of the British Board of Trade. The Council-sponsored Toothill Report on the economy of Scotland in 1961 emphasized “regional” planning and development. It paved the way for the establishment of a Department of Development within the Scottish Office in 1962, under a Conservative government. It influenced the establishment and operations of the (British) Department of Economic Affairs in 1964, under a Labor government. The current Conservative Scottish Secretary is encouraging all other trade and development bodies in Scotland to work through the Council.

Having influence with government is always useful. How useful the Council’s is may be measured, at least in part: All levels of government provide nearly half of all investment in Britain; and central government can determine -where, when and how new or expanded plants will be built, by granting or refusing the Industrial Development Certificates that are required by law.

The Scottish Council may be effective because it can influence a political-economic system that is highly centralized, but the Council is prepared to look the gift horse straight in the mouth. It finds plenty of cavities there, too.

The Council’s first International Forum was on the subject of centralization. Twenty-one months earlier, in March, 1969, the Council published a background paper, the title of which is reproduced above. It is a concise, sophisticated discussion of the worldwide tendency, which is very marked in the U.K., for effective decision-making authority to move higher and higher within organizations, and for the headquarters of the largest companies to be more and more commonly located in one place.

While noting some of the strong forces towards centralization, the paper points out problems that result.

In firms, those with authority may be too far away to make the right decisions for local conditions. Operations may be inefficient if day-to-day problems must be passed up the line for resolution. Initiative may be stifled and training may be incomplete if lower-ranking personnel have little or no authority. Top personnel may deal inadequately with administration or policy or both while trying to do too much of both.

In communities, local affairs of all sorts suffer when the brightest, best educated and most energetic executives see their posts as mere way-stops on the road to the center of wealth, power and prestige. Demands on the time of the few top executives left in provincial centers become excessive. Executives may move, or be uninterested because they expect to move, before they achieve any real understanding of or involvement in the community.

Thus far, the discussion might have been produced anywhere, except that the examples are drawn from Scotland. The tone, however, is distinctive in a way that is interesting, as may be seen in the quotations that follow. (The quotations are extensive because their effect is cumulative.)

The “industrial situation of Scotland” is dominated by “amalgamation of industries” and “stampeding centralization into London.” Strong forces are drawing “decision-makers away from Scotland.” About a tenth of the U.K. population, but only a fiftieth of the decision-makers, are Scottish.

“Scotland would be a poor country today if we had not been able to stem and reverse the rush of new production resources” to the south. And “Scotland will be a poor country in 20 years’ time if we do not similarly succeed in stopping the stampede of the decision-making…apparatus…and men…to the south.”

Scotland’s problems in the 1920s and ’30s “had partly been created by centralized state action earlier.” Centralization is “an affliction which is not new to Scotland.” The concentration of “virtually all government research and development laboratories, and of government research expenditure…in the south of Britain…was the main cause of that…distortion which left Scotland bereft” of new technological industries until World War II.

Government officials still do not see that “government expenditure on technology – the basic source of industrial invention – has a geographical significance” or that “the character and quality of communications shape the country’s industrial structure.”

Central government has “unnecessarily” repeated the London-focused “radial pattern of the railways” in establishing airways, and “even now Scotland has totally inadequate direct routes to the Continent.”

“The money for stereo radio seems to have run out somewhere in the Midlands.” Experimental data links will run from London to Manchester and Birmingham, but it will be years before “Scotland, which needs communications more than the south, benefits from them.”

The headquarters of all the large nationalized industries – the Coal Board, the Steel Board, the airlines – are in London. “The Forestry Commission has recently moved its headquarters all of 50 miles from London to Basingstoke.

“Whenever, in the case of large London-based organizations, such phrases as ‘the special interests of Scotland will be fully considered’ are seen, one may be fairly sure that the real working situation is such that they cannot be given real weight.”

Over many years, centralization has brought “rationalisation” of related industries, with similar effects each time, as when “the formation of the Coal and Hospital Boards…greatly reduced the business…of Scottish companies” in printing and medical supplies.

If decisions on Oceanspan must be “determined by people in London in discussion with other people traveling to and from London, one realizes the inefficiency and loss of drive which would inevitably result….We would be back in the days…when…Scottish Leaving Certificate examination papers were put on a train for London for correction, while the school inspectors got on another train to travel down to London to correct them.”

If the British Steel Corporation is reorganized so that all product division headquarters leave Scotland, “this would…be a deathblow to the prospect of retaining real initiative” in Scotland. “Such a situation must be unacceptable to the Scottish community.”

The head of a large Scottish company has suggested that the Scottish Council move to London where “real influence” may be exercised. “This was not expressed as a policy of despair, but as a realistic assessment of the way things are going. When it comes to the point that such a suggestion should be seriously made, the danger of our situation is evident.”

Centralization threatens “our ability as an industrial community to retain a real degree of independence or of initiative in shaping our future course.” Centralization threatens “the viability of the Scottish community as an independent centre of thought and action.”

“There must…be in Scotland an adequate number of large as well as small organizations which have their heads…in Scotland. This is the only pattern which can maintain in the future a lively industrial community, able to keep the initiative in the International world of industry, and embodying the liveliness and challenge and opportunities which will retain an adequate number of the best young minds in Scotland.

It is “urgent to establish centres of authority within Scotland which can participate in the international industrial forms of the future.”

Let it be made explicit that the Scottish Council (Development & Industry) is not a nationalist organization, at least not in the usual sense of that phrase, and is certainly not in favor of a separate Scottish state. As the quotations demonstrate, nationalists can find a great deal of ammunition in the Council’s publications, but Council staff members repeatedly and emphatically said that they do not, as an organization or as individuals, support the Scottish Nationalist Party.

Yet reading these publications, the feeling grows that the Council is in fact an exceedingly nationalist organization, that the real subject is not business, or Britain; it is Scotland. The real evil of centralization is that it deprives Scotland of what it needs. The real goal of Oceanspan is to make Scotland the center of world trade.

The reference to the nine of diamonds could not be more apt. That is a purely Scottish symbol, as Wild Bill Hickok’s “aces and eights” are purely American.

The case can be explained, in part. The Council is supposed to deal with Scottish problems, so it tends to give all problems a particularly Scottish application. And it is understandable that people working on even the most technical economic issues come to feel strongly about them and to be concerned about their implications and effects on the whole community.

But the case should not be explained away. It would be hard to make a convincing argument that the heated concentration on Scotland, not only in industrial terms but in the broadest terms of community life, was an inevitable result of concern for economic development.

Economic strategies are not developed in isolation. What is interesting is the context which is relevant for the Scottish Council’s thinking.

The Scottish Council might think of development in terms of the entire economy of the United Kingdom, with Scotland largely dependent on English development and able to take advantage of opportunities arising in the larger economy.

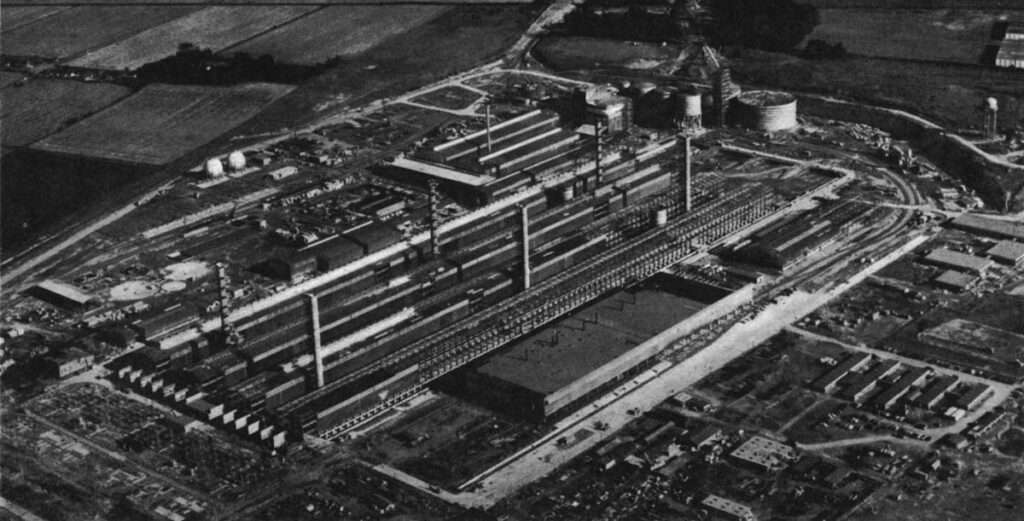

The Highland and Islands Development Board, for instance, is concerned with regional development, but not with independent development. Most of its projects require links to the south for investment, supplies and markets, links not only to the south of Scotland but to England. The Board’s largest project, the 100,000-ton capacity aluminum smelter on the Moray Firth, was primarily justified as a contribution to reducing the dependence on aluminum imports, and to protecting the balance of payments, of Britain.

Or the Council might think in non-national terms. For many businessmen, economists, and some politicians, planning is increasingly in terms of supra-national organizations like the United Nations or, to a degree, the European Common Market, and what might be called extra-national ones like the worldwide businesses whose headquarters may be anywhere and whose staff may come from anywhere. There is also a substantial body of respected exponents of the view that nation-states are anachronistic at best, and the main impediments to peace and prosperity at worst.

It might be expected that the Scottish planners would be most conscious of that sort of context, as leaders of small nations have sometimes been the most fervent supporters of the UN.

It might also be expected that the Council’s emphasis on new technology would lead to strategies for linking Scottish industries, as subsidiaries, to major centers in Europe, in order to prepare for Britain’s probable entry to the EEC.

Instead, the implicit goal of the strategies is to make Scotland a center of world trade, fully the equal of any other center.

To those who think in terms of Britain as a unit, the difference is as great as if a Southern Council in the United States were to talk, not of bringing in industry Like that of the North., not of obtaining a greater share of the wealth, the amenities, or the power of the whole country, but of making the South a distinct economic unit with its own needs and possibilities, its own bases of wealth, power and status, its own role to play in the world.

Oceanspan and the International Forums are obviously related to worldwide developments. But those developments are not central. They are developments to be taken into account in a different context, a context in which Scotland and a feeling and concept of Scottishness are central.

Received in New York on January 12, 1971.

©1970 Scott Keech

Mr. Keech, a free-lance writer, is an Alicia Patterson Fund award winner. This article may be published with credit to Mr. Keech and the Alicia Patterson Fund.