In Sept, 1970

“Some of you guys who got yourselves so wrapped up in the Welsh language might stop back and remember that…what matters is what the little lady spends in the butcher’s shop rather more than the bloody language.”

George Brown, Deputy Leader of the Labor Party, at a campaign meeting in Bangor, Wales.

As electioneering, the statement left something to be desired, but not by Mr. Brown’s opponents.

In its own terms, it presented a barn door of a target. Unemployment in Wales, as in the whole United Kingdom, went up steadily under the Labor government, maintaining a rate about double that of England alone. And real income per capita in Wales is five to ten per cent lower then in England. As one nationalist candidate commented: “To use George Brown’s own gutter language, where is the bloody money?”

As for that phrase about “the bloody language,” it is going to live long in history, at least among nationalists. They can say: “Other politicians may not come right out and say so, but this is what they really think of our language and everything else that is Welsh.” And what the nationalists say may matter, if they can maintain anything like the momentum of the last four years.

Plaid Cymru (pronounced “plide kumree”) literally means Party of Wales but is better known in English as the Welsh Nationalist Party. It was founded in 1925 and fought its first parliamentary election in 1929, winning just 609 votes or 1.6%. It did somewhat better in later contests, but was best known for non-electoral politics for forty years.

All that changed in 1966, when Gwynfor Evans, President of Plaid Cymru, unexpectedly won a by-election in the previously safe Labor constituency of Carmarthen. The party followed up that victory with strong though unsuccessful showings in a couple of other by-elections,

For 1970, Plaid Cymru had high hopes of winning one or two more seats. Instead, it lost the Carmarthen seat, which anti-nationalists interpret as a rejection, or at least a possibly fatal loss of momentum.

Not surprisingly, Plaid Cymru itself takes a different view, and it has some interesting evidence to cite. Fighting all 36 Welsh seats for the first time, the party won 175,000 votes, 11.5% of the total, which was nearly three times as many votes: two and a half times the percentage of any previous effort.

In the 19 districts which were contested in 1964 and 1966 as well as 1970, the party averaged just over 16% of the vote, nearly double its best previous performance.

At the same time, the nationalists say, all the other parties did worse than in the past, Labor lost a net of three seats while recording the lowest vote total since 1945 and the lowest percentage since 1935. The Conservatives gained three seats, but did so with fewer votes than in 1959, the only other year they ever won seven seats in Wales. The Liberals held their one Welsh seat, but finished behind Plaid Cymru in eight districts. The Communists were merely also-rans.

Every party puts the best possible light on election returns, and certainly the party was hurt some by Gwymfor Evans’ loss. In Parliament, he could get headlines, and ask questions the Government would have been happier not to answer.

Still, it isn’t completely whistling in the dark for Gwynfor Evans to say, “There is no stopping us now,” or for Dafydd Williams of the party staff to conclude, “Plaid Cymru has consolidated its position and in now emerging as the only effective nationwide opposition to Labor in Wales.”

Mr. Williams bases his view on a belief that the general election total is the minimum the party can expect to win. In by-elections, he said, the party gains some protest, or “grudge” votes, but in general elections the full resources of the major parties, and the force of the argument that Plaid Cymru cannot achieve real power take effect.

But he was also prepared to concede that the party faces not only all the problems of a third party in an increasingly two-party system, but those of “Anglicization” and of the pull of non-electoral action.

The former refers to the immigration of English people, many of them in retirement, which combines with the continuing emigration of young Welsh seeking jobs to weaken any specifically Welsh program. The process may be drastically hastened if any of the proposed housing projects for “overspill” from Liverpool and the Midlands go through.

The latter highlights Plaid Cymru’s most serious weakness. As an electoral party, it must win at least a majority of the seats in Wales or be a failure, Even then, it would be a small minority in Parliament and would face opposition from Conservatives, the party of Union, but also from Labor which might be sympathetic but would face the prospect of becoming a permanent minority itself without the seats in Wales.

Moreover, Plaid Cymru has some experience itself of being a minority frustrated by its ineffectiveness within the electoral system. In 1936, three of its leaders set a fire at an air base being constructed in Wales despite opposition. Y Tri (The Three) gave themselves up and issued a statement saying in part: “Lawful and peaceful methods have failed to get for Wales even ordinary courtesy from the English Government. Therefore, in order to compel attention to this violation of natural rights of the Welsh nation, we have taken this way, the only way left to us by a government contemptuous of the nation of Wales.”

Plaid Cymru has since renounced all forms of violence, but some members admit that the party statement is not entirely in agreement with every individual member’s views.

In 1966, Gwynfor Evans commented sadly, “The Government does not think anyone serious until people start blowing up or shooting others.” He was referring to bombings at water projects, most of which have been claimed by or blamed on the Free Wales Army.

The main project, Tryweryn, has become a symbol of insensitive, unreachable government. Without rehearsing the chicanery nationalists believe characterized the project, suffice it to say that Parliament approved a proposal from the city of Liverpool, despite the opposition of every member from Wales,

Sabotage was tried twice each in 1962 and 1963, and two other projects were bombed in 1966. Julian Caio Ewans, leader of the Free Wales Army announced: “Pacifism has got the Welsh nationalists no where. Violence is the only answer even if it does include hurting innocent people.”

Plaid Cymru considers the Army insignificant now, and may be right, but the point is not so easily dismissed. Unless Plaid Cymru can achieve some success, people will turn away from it. Most may turn away from nationalism, but there are too many examples, and lately too much evidence that explosives are easier to get than a drink out of hours, for the potential of even a tiny minority to be dismissed.

Dafydd Williams rests his hopes on young people who, he says, are turning to Plaid Cymru and thereby undercutting Labor as Labor once undercut the Liberals, a process that took only about 20 years.

Ostensibly, it is five years to the next election, but some nationalists think Plaid Cymru may get a much earlier chance to show what it can do. There is an idea going around, not only among nationalists, that an election intended as a kind of referendum on the Common Market will have to be held in the next 18 months or two Years. Whether that in realistic or pure pipe dream this writer is not in a position to say.

Background To Nationalism

Y Ddraig Goch, The Red Dragon, is the symbol of the Welsh nation, and Tafod y Ddraig, the Dragon’s Tongue, is the Welsh language. Plaid Cymru wants to preserve both.

Nationalists like to trace the language issue right back to the Act of Union of 1536, one provision of which proclaimed the intention “utterly to extirpe alle and singular usages and customs differing from the laws of this Realme.” Anyone who spoke only Welsh was prohibited from holding any government office.

In 1568, the first Eisteddfod, the gathering of poets and singers, was held. The first suit seeking legal recognition of the language was filed in 1585. The Honorable Society of Cymmrodorion was founded in 1751 to encourage the arts, literature, and science in Wales. It was partly responsible for the publication of books in Welsh, and has played a large role in the establishment of the Welsh colleges and university, the National Museum and Library, and the National Eisteddfod Association. It is still going strong and, ironically, acquired a royal charter and the patronage of the Queen in 1951.

In 1939, 500,000 people signed a petition asking that Welsh be accorded equal status with English. In the last few years, the Welsh Language Society has led demonstrations and civil disobedience, including refusing to pay rates or taxes, or to respond to police summonses written in English. One couple refused to register the birth of a child, and a student declined his diploma, in English. In 1967, Parliament responded with the Welsh Language Act, but the required bilingual forms are not always available, and anyway the Act is just one more unsatisfying sop as far as nationalists are concerned.

While the language issue can thus be traced for more than 400 years, it seems to have become a truly nationalist issue only in the nineteenth century. Until then, despite the Act of Union, English policy was more to neglect than to extirpate. As late as 1890, after all, 90% of the Welsh still spoke the language, and more than half spoke only Welsh. There was dissatisfaction, but no obvious enemy and no clear political policy to follow.

An enemy appeared, however. In 1847, a Commission of Enquiry into the State of Education in Wales concluded not only that its state was deplorable, but that the reason was the continued use of Welsh. That wasn’t all. The three commissioners also decided that the language caused poverty, immorality and crime. The reaction was predictable, especially as evidence accumulated that, by English standards, Wales really was not performing any worse than England on any of the four grounds.

In 1870, the issue became acute when the government took responsibility for schooling and made it compulsory for all- but only in English. No provision was made to teach Welsh even as a foreign language.

Two years later, what is now the University College at Aberystwyth was founded. Lacking rich backers, it was kept going for the first 12 years by small contributions from as many as 73,000 donors in one year.

To an outsider, those 12 years appear crucial, for during them language was made into an issue about which people could do something. People acquired a positive commitment to something all Welsh shared (and still do, in memory at least). It was also the thing which distinguished them from all other people, and which came to stand for all things Welsh. Its decline was then a sign of the decline of Wales. From there it is an easy jump to believing that language, nation and all could be preserved only in a Welsh state.

For those who have made that jump, the context in which all other issues appear has shifted. Members of a political party are divided from members of another by basic assumptions more than by issues. Opponents’ failures are not isolated difficulties, but proof of the need to take power from them, and even what are conceded to be successes are seen as less than what one’s own party could do. Nationalists do all that too, but for them each issue provides evidence of the need to change, not the party but the state. Hence, all English parties are repugnant, and any concessions, such as establishment of a cabinet-level Department of State for Wales, are merely derisory shadows of real self-government.

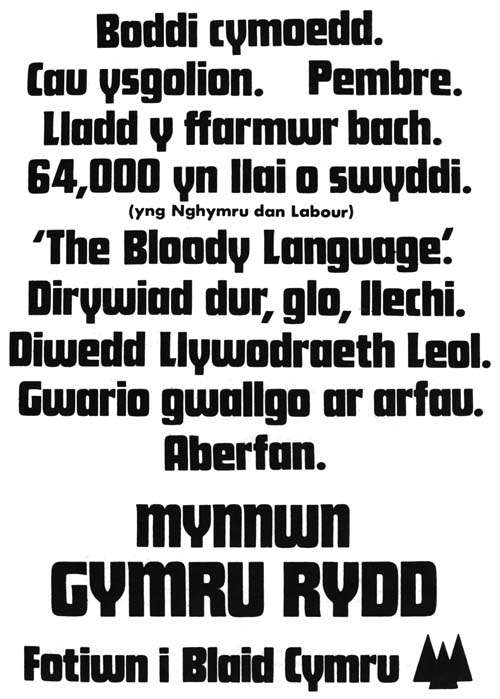

A campaign poster in Welsh, from the 1970 general election. It says:

VALLEYS DROWNED.

SCHOOLS CLOSED.

PEMEREY.

KILLING OF SMALL FARMER.

64,000 FEWER JOBS

(in Wales under labor)

“THE BLOODY LANGUAGE”.

STEEL, COAL, SLATE RUNDOWN.

RECORD ARMS SPENDING

END OF LOCAL GOVERNMENT.

ABERFAN.

LET’S GOVERN OURSELVES

VOTE PLAID CYMRU

On this page, the covers of Plaid Cymru pamphlets.

Most of this is self-explanatory or, in the case of the Aberfan disaster, well-known. The exception, Pembrey, refers to an area of magnificent beaches where the military want to establish a weapons firing range.

The party symbol in the lower right-hand corner, the Triban, represents the mountains of Wales and Plaid Cymru’s three aims: self-government, preservation of national identity, and membership in the United Nations.

If language provided fervor, Home Rule movements elsewhere helped provide a program. Toward the end of the century, the Irish, the Scots, and the Welsh all derived some inspiration from one another. They were largely in agreement on goals, and could look forward with some realism to a day when their combined forces in Parliament would be sufficient at least to so obstruct business that the English would grant Home Rule All Round, They could even hope to part in friendship, since at the height of Home Rule agitation both the Liberal and Labor parties were pledged to Home Rule.

In fact, of course, things didn’t work out that way. The Irish situation exploded, and one result was the loss of the largest bloc of Home Rulers in Parliament. Another was the loss of some English sympathizers who came to fear that Scotland and Wales would end the same way as Ireland.

Then, too, a variety of catastrophes served to divert attention, and not only in England. World War I was followed by depression, a short-lived boom, another depression, World War II, and still more economic troubles. In all the storm and stress, it isn’t surprising that Home Rule dropped far down the list of priorities of even Welsh politicians.

Nationalism languished until recently, when its resurgence has seemed inexplicable to many commentators. While many causes may have played some role, one which seem important is the issue of “big government.”

The problem is hardly unique to Wales. But people who become disturbed by large, remote, bureaucratic government, who come to feel politically powerless, who believe experiments in consultation or regional and local government have failed—to those people, self-government for Wales can appear attractive and, indeed, the only realistic possibility.

Plaid Cymru’s Case

The present situation is unsatisfactory.

Plaid Cymru makes this argument on a number of grounds besides those which have already been indicated. The most important is economic.

As has been mentioned, the unemployment rate is higher in Wales than in England. Plaid Cymru argues that conditions are much worse than official statistics show because of two kinds of hidden unemployment, One is indicated by the “activity rate” (the proportion of those of working age who are employed or registered as unemployed) which is about 10% lower in Wales than in England. The other is emigration, or “mobile unemployment.” From 1921 to 1961, there was a net loss by emigration of at least 500,000 people. Since 1961, there may have been a net gain because of emigration from England, but Plaid Cymru says that the outflow of young people for whom no jobs exist in Wales has continued unabated.

This ties in to other problems. The mines are being closed rapidly too rapidly and with too little retraining or provision of alternative employment, says Plaid Cymru. Small farms are being encouraged to consolidate and reduce the manpower needed per unit of production, but again without enough effort to supply other jobs, according to Plaid Cymru. Transportation in Wales is neglected, as railroads close down but roads are built too slowly to encourage investment; besides, the roads are built run to England instead of linking parts of Wales together.

Another point is that military spending is too high. Plaid Cymru rejects the need for nuclear weapons and other expensive military projects, and believes that defense spending should be rechanneled to social programs.

Then there is the Common Market. Plaid Cymru believes that Wales would suffer severely from Britain’s entry, and points out that Wales will have no independent say in the matter.

No alternative but self-government would be satisfactory.

The alternatives are, administrative devolution, as in the Welsh Office; Home Rule, as in Northern Ireland; and a federal system.

Administrative changes won’t work because, a Plaid Cymru pamphlet says, they cannot transfer “the actual decision-making processes to the people themselves.” J.P. Mackintosh (Labor M.P. for Berwick and East Lothian) says in his interesting book The Devolution of Power that “no amount of regional administrative devolution can make people feel they have more local control.” Thus, the Welsh Office fails because “it is little comfort to us as Welshmen to have an administration in Cardiff carrying out policy decisions taken in London where our elected Members of Parliament form a permanent minority. To be effective devolution must be extended to the legislative and executive spheres of government.”

As for Northern Ireland, the Home Secretary’s recent threat to intervene if the Unionists deposed Prime Minister James Chichester Clark is proof enough that Home Rule does not mean independence.

Home Rule rests on an “unrealistic division of government functions into internal and external affairs,” Thus, agricultural policy might seem to develop, but real control would not if London could decide to join the EEC as a matter of foreign affairs, without regard to the effect on Welsh farmers. In any case, Plaid Cymru argues, even internal affairs would not fully devolve where finances are concerned. If England delegated taxing power, Wales might withhold funds from projects it disapproved, such as defense. But if taxing power were not delegated, England might decline to pay out for policies with which it disagreed, such as further nationalization when the Conservatives are in power, or denationalization when Labor is in power.

A federal system would not work either, If England had votes proportional to its population, the actual relationship to power would not be changed. On the other hand, Plaid Cymru considers it inconceivable that England would accept any less, or would grant the other states a veto power.

Thus, in outline, Plaid Cymru makes its case against what exists, and against suggested alternatives. It goes on to make the case for full self-government.

Self-government is practicable.

First, Plaid Cymru argues, Wales is not too small, There are 30 to 4o independent states with populations as small as or smaller than the 2.7 million in Wales (including Israel, New Zealand, Nicaragua, Liberia and Luxembourg). There is also a fair number with populations not much larger by comparison with the United States or even England (including the Scandinavian countries and Switzerland, all under 10 million).

The next step is economics. Plaid Cymru has published a 288-page economic plan which is hard to summarize fairly because it includes numerous detailed sub-arguments. However, the following main points are made.

Wales could afford self-government. It currently pays as much in taxes as is returned in social service expenditure, as well as its full proportion of defense costs and the national debt. (There has sometimes been talk of “robbery” by England, Dafydd Williams says Plaid Cymru now rejects that position, and that the purpose of totting up the figures is only to show that Wales is not being subsidized.) By reducing defense expenditures by about two-thirds, the planners believe that a Welsh government would obtain funds for development of transportation and industrial estates.

Wales has the resources for modern economic development, especially in plastics and other petrochemical products, and in many kinds of light industry. It has coal and water for power, and ports capable of handling all kinds of shipping up to the new container ships and super-tankers. It has a highly educated and under-employed population (the other side of the employment and migration statistics), It has the technological base and, in the economic plan, the framework for development. By slowing mine closings and farm consolidation, a Welsh government could provide jobs during the transition to other industries, thereby reducing migration both out of Wales and from rural to urban Wales.

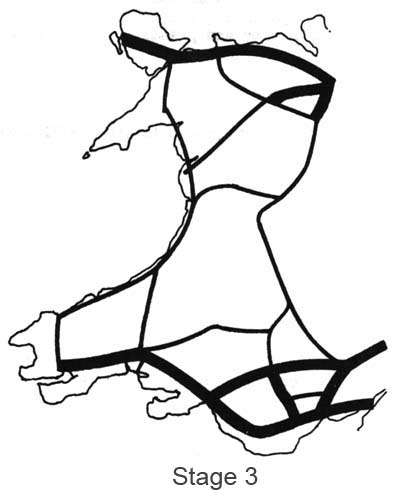

The two-edged case Plaid Cymru makes is graphically illustrated in a page from the economic plan. The map at top left shows that Wales lacks the wide, high-speed roads needed for industrial development and to link north and south.

The other three show what Wales could do for itself.

Heavy Line – National network roads to motorway or dual carriage-way standard.

Thin Line – National network roads of minimum 24′ widhth and distant visibility.

Plaid Cymru does not anticipate unfettered independence. The party economists are well aware that no country, and especially no small country, has an entirely independent economy.

The most important limitation is that Wales would have to remain closely linked to England to keep markets and sources of capital, and to prevent roads and railways from dead-ending at the border. (This is, by the way, one reason for the emphasis on peaceful, electoral politics. Even if violence might achieve self-government, it might also leave so much bitterness that economic cooperation would be impossible.)

Thus, Plaid Cymru wants “freedom but not independence” in the form of self-government within a true British Commonwealth or Common Market, a cooperative enterprise of free and equal men and states.

That would allow England as well as Wales to continue to enjoy the benefits of economic and cultural relations, while England would retain and Wales obtain the power to adopt the policies their peoples wanted in education, social services, industrial development and agriculture, defense, and foreign policy. The problems of central government would be reduced by reducing its size and range of responsibilities, Citizens would gain the “moral value” of membership in a true community, and the social and psychological benefits of identity with a nation possessing the authority and prestige of a state.

A future newsletter will take up the case against Plaid Cymru.

Scott Keech

12 Southwell Gardens

London, SW 7

Received in New York on September 14, 1970.

©1970 Scott Keech

Scott Keech, a free-lance writer, is an Alicia Patterson Fund award winner. This article my be published with credit to Mr. Keech and the Alicia Patterson Fund.