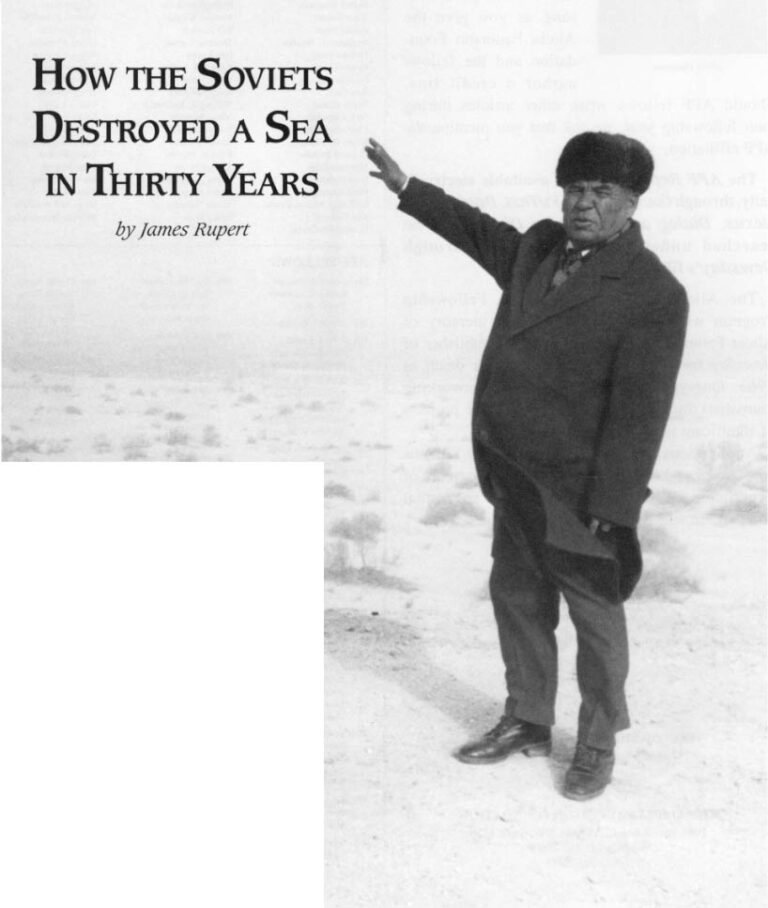

Muynak, Uzbekistan – In this frightened town, life has always meant fishing. Men’s faces are leathered by lifetimes on the Aral Sea; their arms thickened by the weight of countless nets hauled from the waters. The women’s hands are scarred from millions of the slices and chops that remove heads and fins from wet, rough fish at the cannery. In Muynak, there are boats and docks. There are anchors and chains. But there is no sea.

The nightmare began imperceptibly, in the 1960s. Muynak and other towns on the Aral were thriving, hauling 160 tons of fish each day from its shimmering waters. The ovens at Muynak’s massive cannery burned around the clock, cooking sturgeon and carp. The Aral was the world’s fourth-largest lake, bigger than West Virginia, and the live, pulsating heart of a forested oasis amid Central Asia’s dry steppes and desert.

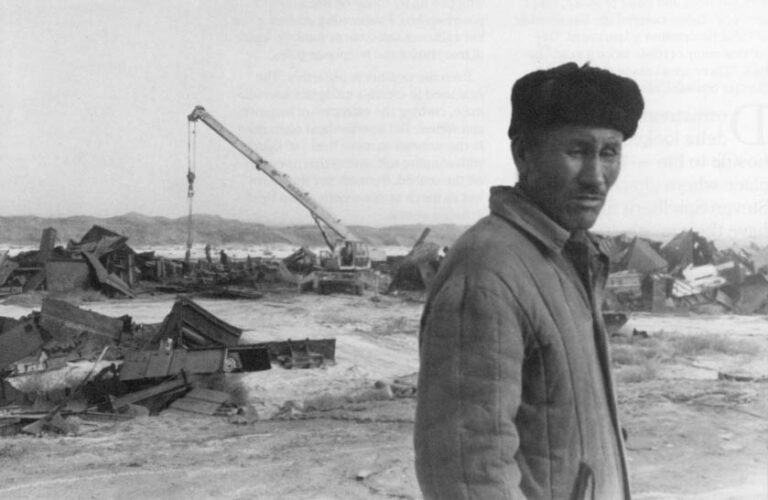

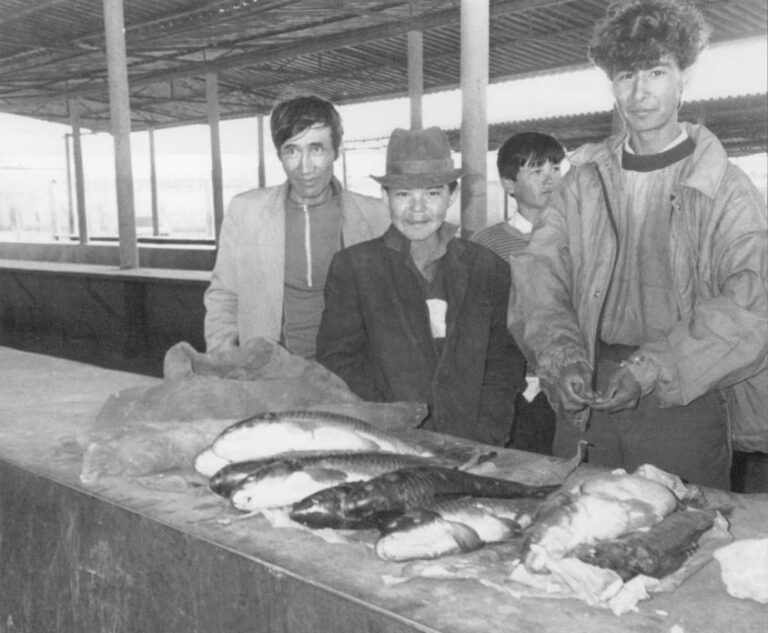

But, by inches at first – then by yards and miles – the Aral began to shrink away from the people who needed and loved it. It receded from the dock-, then from the harbor. Horrified, the townspeople dug a channel across the sands, trying to keep a hold oil the fleeing lake. In one of mankind’s most tragic devastations of the planet, the Soviet Union for 30 years has been diverting the Aral’s feeder rivers into the steppes and deserts to irrigate what was to have been the world’s largest cotton belt. Instead, it has destroyed the Aral and stranded this fishing town on the bitter sands of a new desert. Muynak has found a way to survive for the moment, but the moment will not last long. The fish cannery in the desert now packs fish hauled by rail and truck more than 2,000 miles from the Baltic Sea. To get the tin for its cans, the cannery barters scrap iron. It has sent a crew of former fishermen out onto the lakebed to chop up the town’s former fishing boats, which lie rusting in the sand dunes where the lake left them behind. The boats will soon be chopped and sold – and the Baltic suppliers of frozen fish may soon demand hard cash, instead of the vegetable oil the cannery is currently bartering. “We are looking for new ways to keep ourselves working,” said Dowlbai Kairniyazov, a plant manager. He speaks optimistically of getting more fish supplies from the Caspian Sea or from local lakes. The decisions of Soviet authorities – unquestioned for seven decades -had nearly unlimited opportunities to create environmental disaster. With its grandiose cotton plan in Central Asia, it ruined an entire watershed -drying up 75 percent of the Aral; making the region’s weather more extreme; polluting and salinating thousands of miles of rivers and vast tracts of farmland; sickening millions of Central Asians with overuse of pesticides, fertilizers and defoliants; and destroying the region’s natural economy. There is worse news, While a single Soviet state created this disaster, it is now left to five newly independent and impoverished Central Asian republics to grapple with it. Travel and interviews in Central Asia during the first 10 months of the these republics’ independence suggest that very little will be done in the foreseeable future – and that the people of Muynak and the Aral region are condemned to living poor, shortened and sickened lives.

THE CONFIDENCE OF ABSOLUTE POWER

The destruction of the Aral began in Moscow in the 1950s, when Soviet economic planners decided, with the confidence of people wielding absolute power, to order the transformation of Central Asia’s dry lands into the world’s largest cotton belt.

The planners’ imagination was immense, their logic simple. They would divert the vast waters of the Amu and Syr rivers into thousands of square miles of adjacent desert and steppe.

The inevitable decline of the Aral would pose no problem. According to some versions of the proposal, the lakebed itself would be turned into a zone of cotton and rice farms. “They decided that the sea was not necessary…that the value of the cotton would be greater than the loss of the fish,” said Yusup Kamalov, an environmentalist and energy researcher in the Aral region who reported seeing maps of the plan.

Beginning in 1960. the state built dams and reservoirs on the Amu and Syr rivers. It dug canals to carry their waters into the desert, razed riverine forests and built state-run cotton farms in their place.

While Moscow ordained the cotton plan, the political elites of the republics -especially the powerful political bosses of Uzbekistan – were able to direct much of the spending. They channeled money, jobs and reservoirs into favored constituencies on upstream sections of the rivers. The result is visible on airline flights over Central Asia. Upstream, around the Uzbek capital, Tashkent, and the influential Fergana Valley, tight networks of irrigation canals and constellations of reservoirs glint in the sun.

Downstream, in the politically weak Karakalpak region that includes the southern Aral Sea, water is scarcer – and polluted with the upstream’s agricultural runoff. Ethnic Karakalpaks, including Abdulkarim Teleyuov, a longtime Communist Party leader in Muynak, accuse the powers in Tashkent of needlessly hoarding the Aral’s water. Teleyuov ticked off the names of upstream reservoirs that lie said hold 70 percent of the annual flow that the Aral should naturally receive.

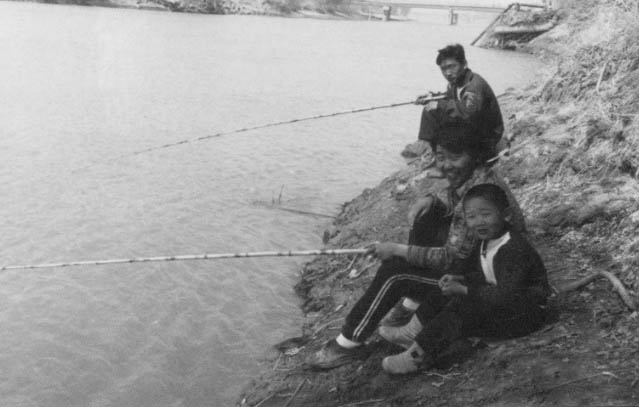

“This year we got enough water from the Amu to fill” some local lakes left behind by the Aral’s retreat arid “help us raise fish,” said Teleyuov. “But in many years, we get no water…We never know from one year to another what we might receive, so we cannot plan for either fishing or farming,” he said.

Uzbek Water Resources Minister Rim Giniyatullin has told reporters that I Uzbekistan uses its water efficiently-that there is nothing extra to send downstream to Karakalpakstan and the Aral.

But the leading western specialist on the Aral Sea disaster appears to disagree. Philip Micklin, a geologist at Western Michigan University, has estimated that as much as 40 percent of the water diverted from the Aral’s rivers is lost before reaching the fields it is meant to irrigate. The water evaporates from reservoirs or seeps into the ground from thousands of miles of unlined canals dug through porous soil.

The inefficient use of irrigation water is not merely wasteful; it can be killing to the land. Where unlined canals or over irrigated fields seep water, the under ground water table rises, sometimes to the surface. As it does so, it often accumulates subterranean salts that are left to encrust and ruin farmland.

During the 1960s and ’70s, the Moscow planner-, calculated the amount of cotton that their newly irrigated lands should produce and ordered Central Asia to deliver it. The entire economy warped itself around the goal of “fulfilling the plan.” Students were sent from school each year into the fields to pick the cotton with the workers. People recalled work brigades that, pressured by their bosses, falsified figures, soaked their cotton with water -and even emptied their cotton-stuffed mattresses – to add to the tonnage.

Under such pressure to produce, state run farms dumped as much as 530 pounds of fertilizer per acre on the fields each year, compared with the Soviet average of 27 pounds. Defoliants (used to ease the harvest by stripping leaves from the cotton plants), fertilizers and pesticides used on cotton applied an average of 48 pounds of poisonous chemicals to each acre, according to Soviet press reports in 1988.

For decades, clean water from the rivers upstream has washed across these fields heavy with salt, fertilizers and pesticides -and drained back to the rivers to irrigate more fields, or serve as drinking water, downstream.

UPSTREAM, DOWNSTREAM

In visits this past spring to towns upstream and downstream on the Amu River the contrasts in people’s lives were stark. In Termez, 680 miles upstream from Muynak, people worried about the collapse of the Soviet economy. Still, virtually everyone interviewed said they had the best standard of living in Uzbekistan – maybe in the former Soviet Union. The Sunday market displayed piles of fruits and vegetables watered from local reservoirs. Seen from a plane, the upstream valleys of southern Uzbekistan and Tajikistan are a patchwork of green fields laced with silvery irrigation canals and ditches. Tomatoes, cucumbers, potatoes and other produce, made into local dishes covered the dinner table in Tahir Rakhrnanov’s apartment. “We harvest many of those twice a year,” he said. “There aren’t many places in the (former Soviet) Union that can do that.”

Downstream, the Amu delta looked like a planet hostile to life – the sort of place where characters in a Steven Spielberg film are to have their mettle tested.

Even in springtime, the place seemed barren. Roads stretched through gray-white lands, always toward a horizon fogged by curtains of blowing, salty dust whipped up by winds off the Aral’s exposed seabed. Evaporating ground water left collars of salt crust around the bases of tree trunks and telephone poles.

Even the weather is unearthly. The Aral used to create a moderate microclimate, curbing the extremes of summer and winter. But now the heat often rises in the summer to more than 100 degrees, with stinging salt storms that sweep in off the seabed. Farmers say they have lost as much as two months from their growing season.

“At least 80 percent of Karakalpakstan’s land is salinized,” said Sabir Kamalov, president of the Karakalpak Academy of Sciences. “Its productivity is cut (by) anywhere from 20 percent to 70 pet-cent.”

Near the delta town of Chimbai, Turehbai Telegenov, a 37-year-old unemployed accountant, struggled against the odds to coax vegetables out of a half-acre plot of land. Twenty-five years ago, he said, when the Aral still was nearly whole and before the Amu river waters were so heavily salted, “we used to grow every thing here.

“Ten years ago, we still had woods and apple orchards and grapes,” he said, but the rising water table drowned them from the roots.

As Telegenov’s four children played in the salt-crusted dirt, he and his wife struggled to erect a reed fence around the field. Telegenov said lie would use well water, which is not as saline as that of the irrigation canals, “to wash the salt … most of it … out of the field. Then I will use manure to improve the soil and we will grow tomatoes and cucumbers for our family.”

“EVERYBODY IS SICK”

Karakalpakstan’s dirty downstream water is used not only for farming, but for drinking – the major cause of what health officials in this region say are epidemic levels of hepatitis, cancers and anemia.

One Sunday morning, at the weekly bazaar in Nukus, the Karakalpak capital, Aikhan Kulsiyityeva, 69, sat on the pavement behind her children’s clothes for sale and lectured a visitor on the difficulties of life in Karakalpakstan. “Everybody is sick. Our legs and heads hurt. Fifty percent of the people in Karakalpakstan are sick,” she said.

“There is no clean water. If you make tea and you pour milk into it, it all curdles from the salt,” she said. “You shouldn’t eat or drink what we have here. We drink green tea and try to make it very strong. But it’s salty, too.”

In Nukus, chlorine is added to the water, which is taken from nearby canals. In smaller towns, “we take the water from the canals or the tap and let it stand for three or four days,” to let the sediment settle out, said Yusupbai Ishanov, an agricultural researcher in Chimbai. “It’s not clean, but you can drink it.”

In 1979, the Karakalpak immunological service counted 32 percent of drinking water samples taken in the region unfit for human consumption. In 1989, the agency’s director said, the figure was 83. 2 percent. The water is heavy with chlorides, sulfates, pesticides and heavy metals, health workers in Nukus said – and those same compounds are measured in locally grown food – and the breast milk of nursing women.

Oral Ataniazova, director of Karakalpakstan’s institute of women’s and children’s medicine, said she advises wealthy women not to breastfeed-but to make infant formula with water that has been boiled to kill germs, then frozen to reduce minerals. With village women, Ataniazova said, she tells them simply to breast-feed, because they lack the fuel and freezers to clean their water. Infant mortality is nearly 100 per thousand in some districts of Karakalpakstan. That rate, 10 times the U.S. average, is similar to those of Nigeria and Uganda.

Unlike the European peoples of the former Soviet Union – the Balts and Ukrainians and Russians who marched and voted and demonstrated for an end to communist rule – the Central Asians have not channeled their discontent into political demands. They continue to be ruled by authoritarian bureaucracies that simply have dropped the label “communist.”

Especially here in relatively isolated anti unchanged Karakalpakstan, it does not even seem to occur to most people that they can change their political system. In any case, said Sabir Kamalov, “We cannot fight Tashkent.”

Kamalov and his son, Yusup, the, energy researcher, have been met officials of all five Central Asian republics, speaking of the need to reach a regional agreement on the sharing of river waters that will include the goal of sending more clean water downstream to the Aral. While officials from some republics have been receptive, “We cannot find a common language with the Uzbek government,” he said. The people making decisions there “have been in charge of their water policy for a long time.”

People seem more exhausted than angered by their plight. “The illnesses of our people sap our strength,” said Sabir Kamalov. “I would cry but I have no more tears. In five years, we won’t have any more emotions left at all.”

©1992 James Rupert

James Rupert, of the Washington Post’s foreign staff, has spent the last year living in central Soviet Asia on an Alicia Patterson fellowship.