(Tales of the Vienna Opera)?

VIENNA — This was once a great city, the capital of a mighty empire.

It was a good city, a cosmopolitan one, freely receiving and warmly embracing people from all over Europe.

It was an inspiring city, home to giants of music and literature.

And, throughout its greatness, it was always a hard city, cruel to its best, crippling and killing those very men who gave it their work and thus its greatness.

It’s all gone now.

The greatness, the goodness, the inspiration are not here any more.

Hardness to the exceptional, the creative, the great — that remained, but, with the diminishing target, the city’s collective cruelty somehow became smaller, pettier, triter, taking forms fitting its new objects — jealousy, hair-splitting, impotent criticism, whining quarrels.

Greatness went with the Empire a half a century ago, but leaving behind, to this very day, a gigantic bureaucratic machinery which is now choking the country and the individual with its tentacles of red tape.

Goodness, laughter, kindness, gemutlichkeit retreated into the countryside, leaving Vienna, the head of this historically hydrocephalic country, non-Austrian or even un-Austrian.

Instead of a cosmopolitan city, it has become a metropolitan village dominated by alienated and rootless Czechs, Hungarians, Slovaks, Croats, Romanians, Italians, Germans, Albanians…people who have lost their national and ethnic identity, but arrived here too late to become part of the whole. The “whole”, the spirit of Vienna, must have been crushed under the boots of the German cousins, the rubble of the war, or the decade of occupation. More likely, somehow during those two decades between the brown shirts and the red flags, “Vienna”, as an abstraction, changed from an almost tangible atmosphere into an insubstantial myth.

And inspiration, the fertile environment for the creation of works of art or encouraging contributions to science or the humanities, inspiration went too, because it cannot be gained from the small or the shrinking.

No great music or literature came out of this city since the time “Vienna” disappeared, since the petit came to rule instead of the bourgeois, white-collar civil servants instead of unemployed but working intellectuals, espressos instead of cafes, mindless laziness instead of creative leisure.

A dark picture, perhaps, but true, especially to those coming to Vienna after all those years of hearing and reading about “Vienna.” A dark picture, by all means, but providing a very good contrast for talking about the shining bright light of the city — its performing arts.

Notwithstanding the continuing decline of life’s quality and art’s production, or because of this decline, most of the city’s many theaters and the State Opera are still up there, among the greatest in the world.

And, while there may be a question or two about the exact position of Vienna theaters in the German-speaking world, there is no doubt about the place of the Vienna Opera, the subject of this article, in the entire musical universe.

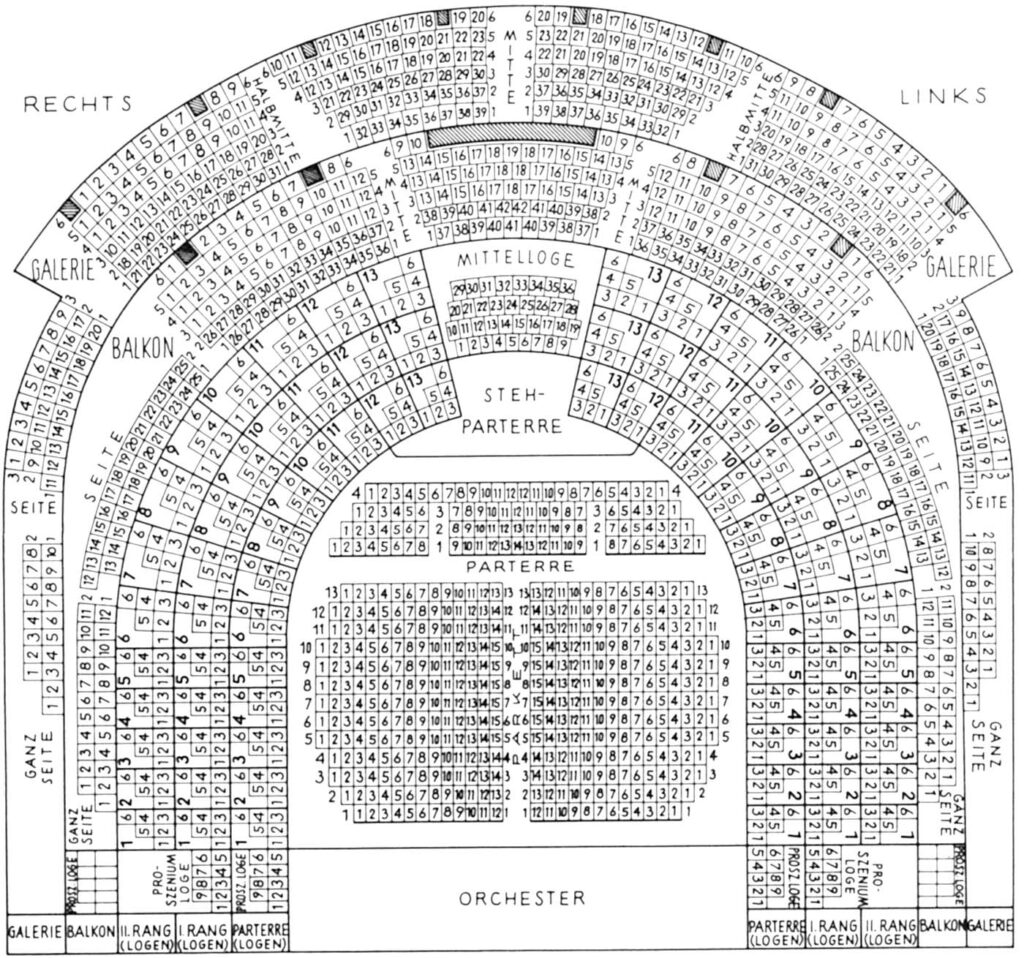

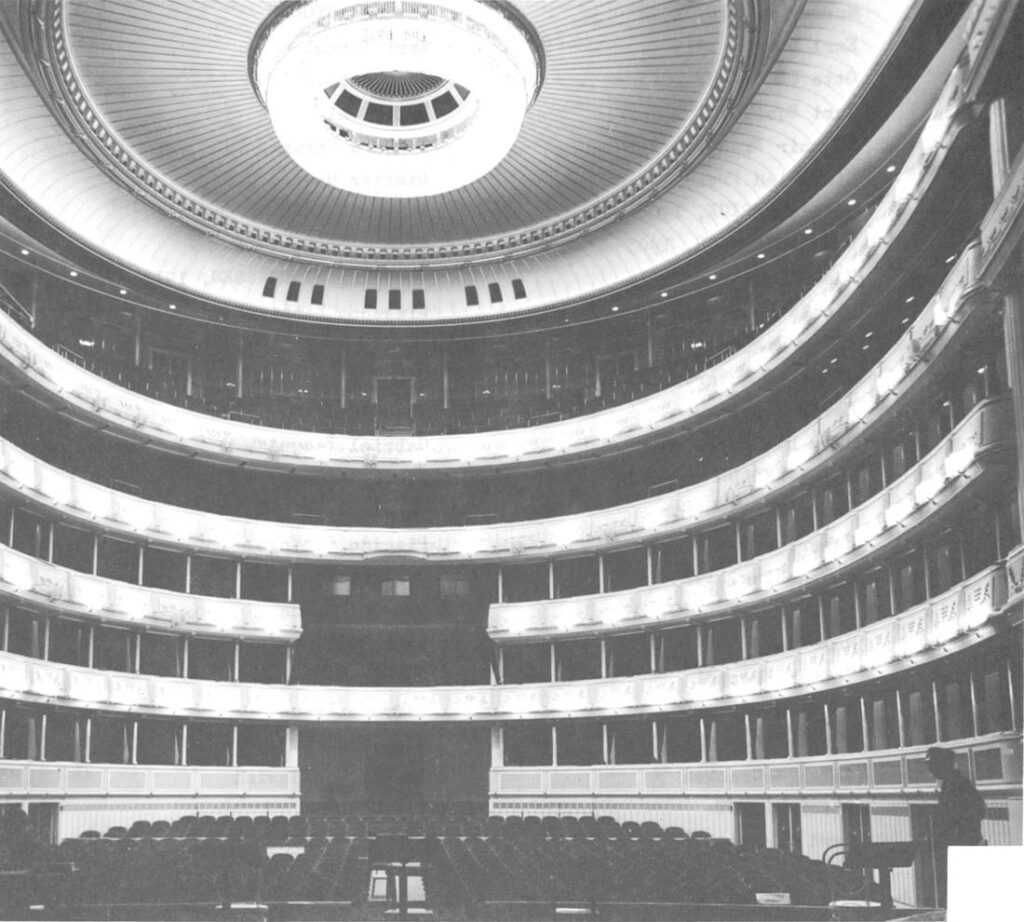

In that sprawling and yet wonderfully solid building on the corner of Kartnerstrasse and, the Opernring, a miracle takes place every night from September through July.

Miracles are hard enough to come by, but the uniqueness of this place, the Staatsoper, is that it practically guarantees one every single night, seven times a week, ten months a year.

It doesn’t matter what the opera is, who the singers are, how the orchestra is doing — every night, there comes a moment (and sometimes even more) of joy, fullness, perfection, Catharsis.

There is no Richard Strauss writing music in Vienna today. But there is Birgit Nilsson creating those moments of miracle in Elektra or Sena Jurinac in Ariadne on Naxos. Even Gottfried von Einem prefers Switzerland, but it is here, at the Staatsoper, that Eberhard Wächter makes Danton’s Death light up or Jeannette Pilou brings meaning to Der Prozess.

If the singers fail to provide magic, there is Horst Stein directing long segments of perfection in Götterdämmerung or the choir doing wonders in the Flying Dutchman or Franco Zeffirelli giving a stunning set to La Boheme.

Even if the lightning of creation ceased to strike here, the fireworks continues on the stage.

Sure, it also happens at the Met or in La Scala or Rome or even at Covent Garden.

But the point of the story here is that the Staatsoper continues to provide a very high frequency of ecstasy in spite of the greatest possible obstacles it can encounter. What’s more, these obstacles are created and nurtured lovingly by the Staatsoper itself and/or by the very city it graces.

The Staatsoper, the crown of this hard and cruel city, continues to thrive through well-executed attempts at suicide – only, with the diminishing proportions, there is a bit less blood today.

Suicide, tragic and actual, is the very first example of this strange heritage, an example from the moment of beginning.

When the Staatsoper opened on May 23, 1869, with Don Giovanni, neither of its two architects attended the gala evening. One of them, Eduard van der Nüll, killed himself because of the malicious, spiteful criticism the building was receiving from the friendly Viennese. The other, August Siccardsburg, weakened under the constant bombardment, died a few days after van der Nüll’s funeral.

Within a few years, all critics talked about the Staatsoper as the finest example of the Ringstrasse architecture. The men who built it never had a chance to hear the praise.

Johann Herbeck, one of the first directors, resigned under fire in 1875 and died soon afterward.

Franz Jauner, responsible for attracting both Wagner and Verdi to the Staatsoper, lasted five years before giving up.

Gustav Mahler himself resigned in a storm, after years of bickering and intrigues, topped by the rejection of Salome by Court authorities as “unsuitable” when Mahler scheduled it for production in 1907.

Mahler’s successor, Felix Weingartner, lasted three years and gave way to Hans Gregor who somehow managed to stay on until 1918 by which time, with the demise of the Empire, the Staatsoper actually became the State (rather than the Court) Opera.

The next victim was Richard Strauss. He infuriated people by presenting works of Bittner, Kienzl, Schreker, Schmidt, and Korngold – trying to give Austrian composers a chance at least in Austria. “The inevitable intrigues pursued their tortuous course”, says the Staatsoper’s official history, and so Strauss left.

A second attempt by Weingartner, the regimes of Erwin Kerber, Lothar Muthel (appointed from Berlin), and Karl Böhm produced similar clashes.

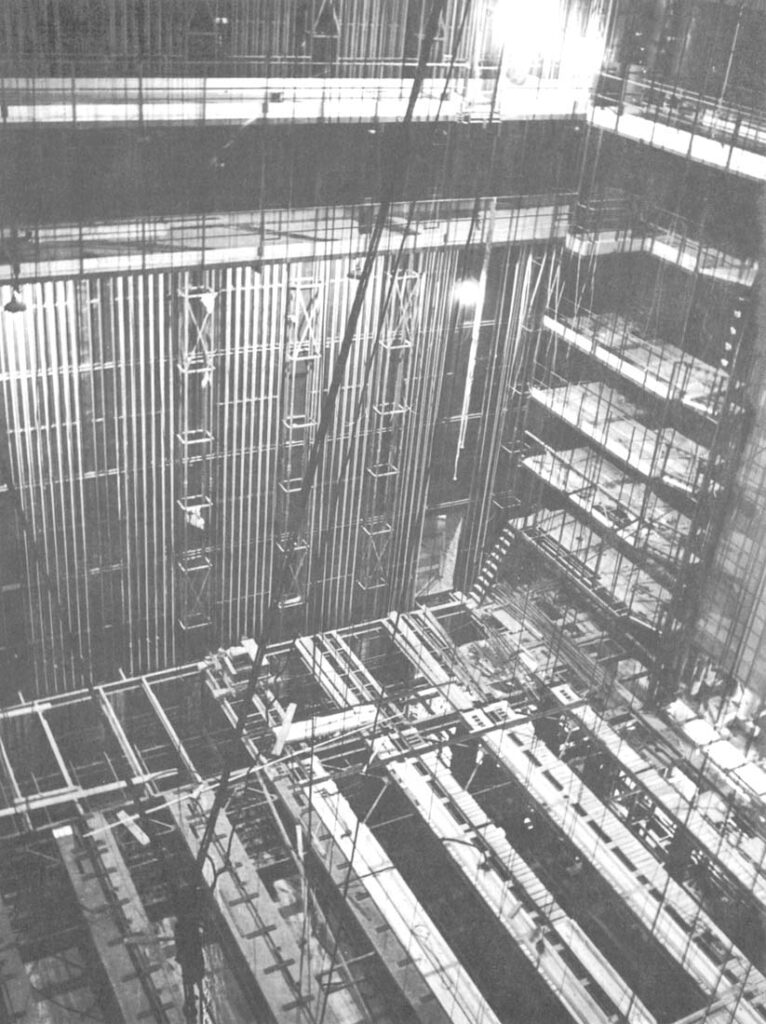

The period until 1955 was somewhat complicated by the fact that the country (along with the Staatsoper) was first being run from Berlin (where, by the way, Karajan directed the Opera throughout the war years), then devastated, and then for 10 years there was no Staatsoper at all, the building itself having fallen victim to bombers of a still-unidentified nation.

Then there was an absolutely superb Fidelio on opening day, Nov. 5, 1955, directed by Karl Bohm, head of the Staatsoper once again. Only four months later, things have gotten so bad that Bohm, frustrated practically out of his mind, told newsmen that he will “not sacrifice a world career for Vienna”, was booed by the audience and the orchestra the same night on his way to the rostrum, and resigned the next day.

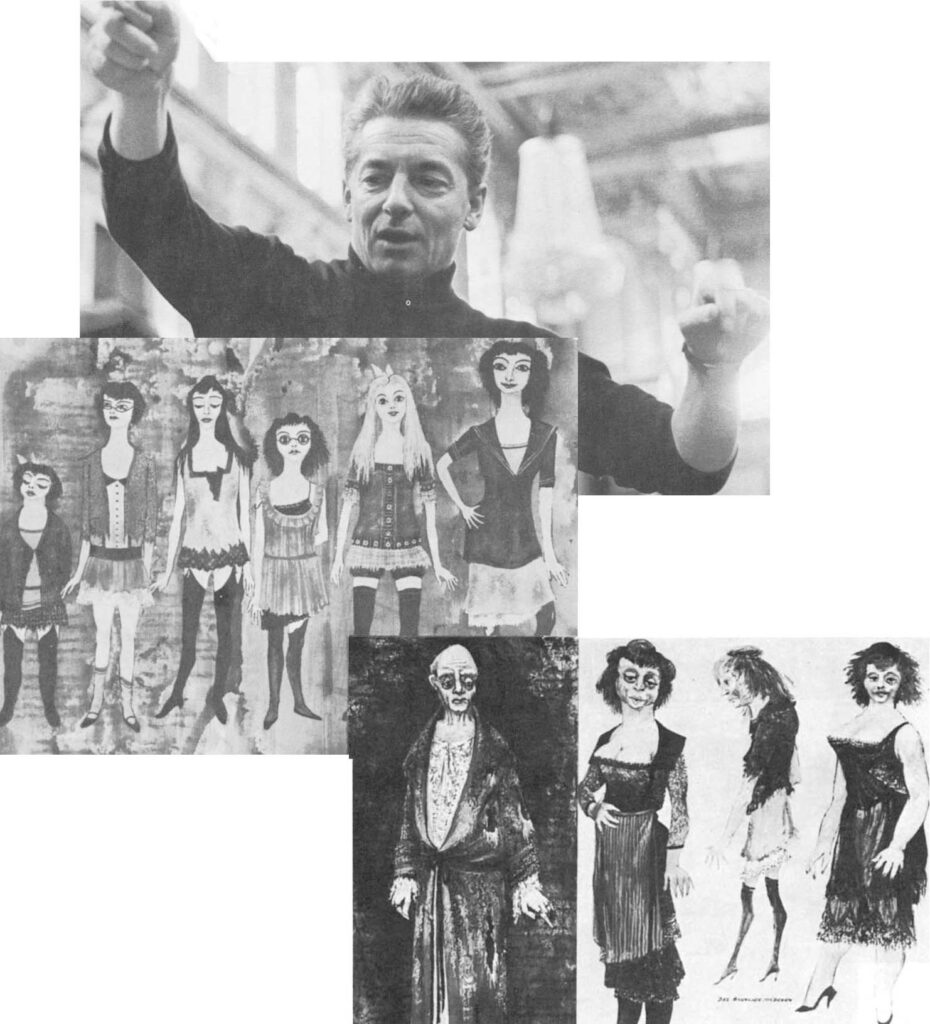

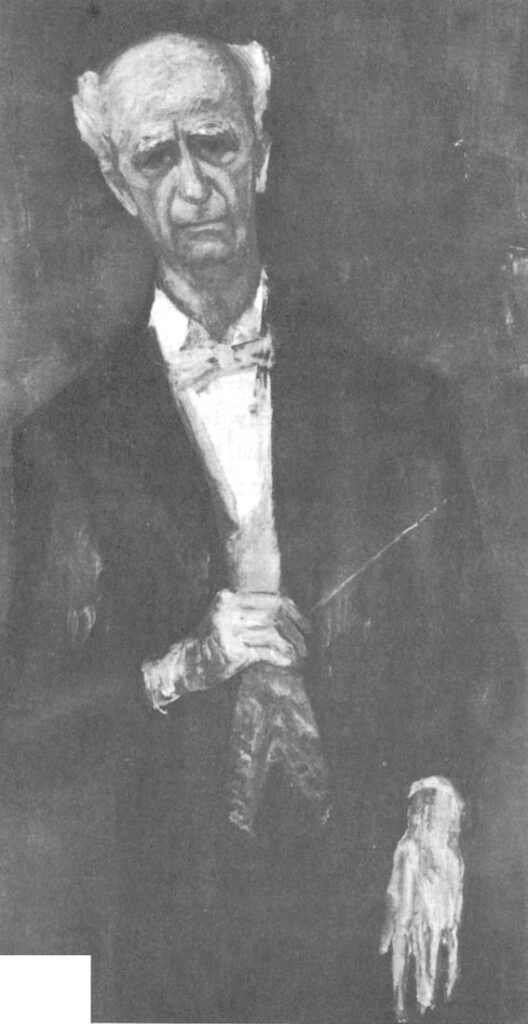

And then came the era of Herbert von Karajan, an era of brilliant triumphs and…constant quarrels.

All the people “done” in by the Staatsoper’s destructive forces (which strangely coincide with its creative ones) carried their own share of responsibility for their strife and woe and Karajan was no exception.

But, while Karajan and his predecessors were possibly all very difficult people to live with, the pattern of wearing them all down, one by one, is too telling, too consistent in fixing the blame: it is the Staatsoper and Vienna that cannot be served long without facing mental breakdown and/or early death.

Oh, everybody said (especially after Karajan left) that the years between 1957 and 1964 were wonderful, that the Karajan era was inspiring and that he left his mark upon all the performances, especially – says the official narrative – “works by Mozart, Wagner, Beethoven, Verdi, and Puccini.” A rather nice range.

But…he had a “predilection” for Italian stars. Quarreled with colleagues. Was rude to musicians. Favored certain singers. Antagonized the union. Demanded too much work. And so on.

Therefore, “greatest” or not, off he went (back to Berlin, incidentally) and there stood the Staatsoper – without Karajan.

That was six years ago. And the Staatsoper is still up there, primus inter pares, home of consistent brilliance, great and wonderful.

How can they do it?

How can the Staatsoper afford to give the boot to Karajan (as it did in the past to Mahler and Strauss and the others) and remain the Staatsoper?

The answer is that the Staatsoper symbolizes the triumph of an institutional myth over the individual. Any individual, even Karajan.

For the sake of that very real myth, a collective charisma, people will make sacrifices and do their best and end up producing greatness, night after night.

“Vienna”, it was stated here, cannot be found in this city any more. But the “Staatsoper” is here in the very building bearing the name of the legend and continues to issue a brilliant sound with or without a hundred Karajans.

How does an “operational myth” work?

Suppose you want to be a violinist. Finish high school then and forget about “gainful employment” or the like. Spend a few years starving, studying, practicing, working, day after day, without ever having money.

Then hit the jackpot. Through a rare combination of talent, persistence, and luck, you get a job with the Vienna Philharmonic and play at the Staatsoper.

Reward of rewards.

More specifically, $54.31 a week.

For that, you will play at 20 performances each month and attend 100 rehearsals each season and, of course, learn your part at home. In your remaining time, you can try to make a living. But you do it…because you are with the Vienna Philharmonic and the Staatsoper. In 20 years, you’ll make $100.05

But you’d rather sing. Unfortunately, Birgit Nilsson you’re not. A nice voice, worth working on it, so you do, taking lessons and, again, skipping some “gainful” opportunities.

It takes a long time, but finally a friend of a friend drops a word in the right place, you get an audition and, ecstasy, you are now in the Staatsoper choir.

That will bring $34.30 a week for roughly the same schedule the orchestra has. It’s more difficult to get an outside job, but if your voice keeps up for 20 years, you’ll hit the top — $81.19. After that, there is a modest pension to look forward to, and a thick album of yellowing pictures…me in the Staatsoper.

Outrageous, you say,

Yes and no. For the people getting these ridiculous wages in exchange for producing something quite priceless, it is outrageous.

But for seven million Austrians, every one of whom – man, woman, and child is paying one whole dollar a year to keep the Staatsoper going, it’s not so terrible…too much even, some say, especially the 6,950,000 who never get a penny’s worth out of their dollar.

(A parenthetical question: if the same per capita subsidy was to be given to the Metropolitan, what kind of sound would come out of Lincoln Center for $200 million on top of receipts? But that’s another story.)

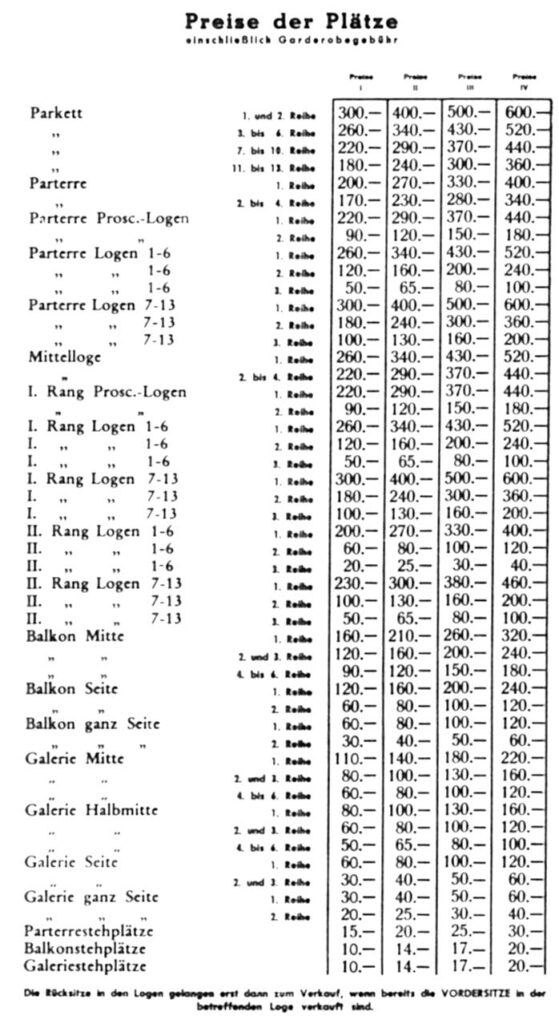

The funny thing is that with all that subsidy, tickets are very, very expensive – with the exception of some standing places and “obstructed view” seats, which go to the students who are just beginning to, sacrifice their lives for the sake of the great legend. (“You begin by sacrificing yourself for what you love”, Shaw said, “and end up hating what you had sacrificed yourself for”. That could be one explanation for the venom flowing freely inside and around that building.)

Now, there is an obvious discrepancy between those wages mentioned and the subsidy (to which about $3 million may be added in receipts for a total budget of approximately $10 million). Using the roughest figures and averaging salaries, it appears that the orchestra and choir (plus pensions) use up about $1 of the $10 million — where does the rest go? (See Appendix III on finances.)

It must pay for all expenses of the house, new productions, and — more than half of the total — for the salaries and pensions of solo singers, directors, and guest artists.

The following list of “member soloists” on contract is quite astonishing. There is no other opera house in the world that has such “duplications” as the Staatsoper — three or four of the top half dozen voices available for certain roles or “sounds.”

Men | Women |

Ewald Aichberger Giacomo Aragall Hans BEIRER, 19 Walter BERRY, 1 William Blankens Hans BRAUN, 19 Reid Bunger Hans Christian Carlo Cossutta Jean Cox Oskar Czerwenka Anton DERMOT Murray DICKIE, Karl DÖNCH, 19 Otto EDELMAN Kurt Equiluz Tugomir Franc Siegfried Frese Gottlob FRICK, 1 Karl FRIEDRICH Vladimiro Ganzar Nicolai Ghiaurov Mario Guggia Frederick Guthrie Heinz Holecek Hans HOTTER, 1909 Heinz IMDAHL Manfred Jungwirth Robert Kerns James King, 1925 Peter KLEIN, 1907 Waldemar KMENTT, 1929 Walter Kreppel Erich KUNZ, 1909 Herbert Lackner James McCracken Erich MAJKUT Gerd Nienstedt Juan Oncina Ljubomir Pantscheff Kostas Paskalis Alois PERNERSTORFER Harold PRÖGLHÖF Karl Ridderbusch Paul SCHÖFFLER, 1897 Peter Schreier Hans Schweiger Mario Sereni Cesare Siepi Fritz Soerlbauer Gerhard STOLZE Karl Terkal Jess Thomas Fritz Uhl Gerhard Unger Dimiter Usunow Eberhard WÄCHTER Otto WIENER, 1916 Wolfgang WINDGASSEN, 1914 Giuseppe Zampieri | Arleen Auger Ruthilde BOESCH Lisa della CASA, 192 Mimi COERTSE, 193 Biserka Cvejic Laurence Dutoit Anny Felbermayer Christl GOLTZ, 1920 Reri Grist 22 Gertrude GROB-PRA Hilda de Groote Hilde GÜDEN, 1918 Judith HELLWIG Dagmar HERMANN Grace Hoffman, 1925 Renate Holm Elisabeth HONGEN, Gertrude Jahn Gundula Janowitz, 19 Gwyneth Jones Sena JURINAC, 1922 Hilde KONETZNI, 1 Margarita Lilowa Wilma LIPP, 1924 Vera Little Emmy LOOSE, 1919 Christa LUDWIG Liselotte Maikl Erika Mechera Olivera Miljakovic, 1939 Melitta Muszely Birgit NILSSON, 1918 Jeanette Pilou Lucia Popp, 1939 Regina Resnik, 1929 Hilde RÖSSEL-MAJDAN, 1911 Anneliese ROTHENBERGER Leonie RYSANEK, 1929 Lotte RYSANEK Gerda SCHEYRER, 1921 Graziella Sciutti Irmgard SEEFRIED, 1918 Margaret Sjöstedt Hanny Steffek Teresa STICH-RANDALL, 1922 Rita Streich, 1923 Claire Watson Felicia Weathers Rohangiz Yachni Hilde ZADEK, 1920 |

GUESTS | |

Theo Adam Gabriel Bacquier Piero Cappuccilli Carolo Cava Placido Domingo Geraint Evans Nicolai Gedda Tito Gobbi Zoltan Kelemen Alfredo Kraus Aldo Protti Franco Tagliavini Ivo Zidek | Ingrid Bjoner Inge Borkh Ludmila Dvorakova Ruth Hesse Nadezda Kniplova Lydia Marimpietri Martha Modl Anja Silja Milka Stojanovic |

A magnificent list, making it rather unimportant who the director is. But it raises some questions. First, the “chamber singers”, the most distinguished members (last names printed in capital letters) who receive the title of Kammersänger, second only to absolute top title of Ehrenmitglieder or “honorary member” (the only active singers in that category are Birgit Nilsson, Irmgard Seefried, and Anton Dermota). The interesting thing is who are not on the Kammersänger list. For instance: Gwyneth Jones, Jeanette Pilou, Rita Streich, Claire Watson, Regina Resnik, Nicolai Ghiaurov, Robert Kerns, James King, James McCracken, Cesare Siepi, Jess Thomas – a rather consistent list of “foreigners”, disregarding recognition elsewhere, popularity, and guest- or recording pay scales.

The other point is the familiarity of most names from long-long way back. To make this even clearer, a few of the known birth dates are indicated (in the case of the ladies, just an approximation for which no responsibility will be assumed).

The first point, about the list of honor, indicates only a slight change in

the Staatsoper: instead of Karajan’s alleged pro-Italian bias, it now has an anti-Anglo-Saxon one. But the second, about the age, is more important. Although the “operating myth” of the Staatsoper often results in singers on the wrong side of 60 making a miraculous “just one more effort”, turning the clock back 20 years, there is a problem there.

It is a problem not in the form of clear and present danger, but rather in a hint of what is to come in, say, a decade unless a more active recruiting program is started – something neither Karajan nor the present management cared for. Meanwhile, fortified by the legend, aging singers deliver their share of the daily miracle and young ones brave years of struggle against lack of opportunity and recognition…because it’s at the Staatsoper.

Besides footing the bill for that spectacular group of singers, the Staatsoper must also cover the expense for the world’s longest season: a performance every night from Sept. 1 through June 30 (except for Christmas Eve, Good Friday, and the night before the Opera Ball) plus matinees – 300 performances per season.

What are these 300 evenings and afternoons filled with in the post-Karajan era?

The following is a tabulation of the repertoire from Sept. 1, 1966 to Feb. 28, 1970 – with only six months of the 1969/70 season available at the time of writing.

1966/67 | 1967/68 | 1968/69 | 1969/70 | |

Beethoven | 10 | 10 | 8 | 2 |

Berg | 3 | 2 | 8 | 3 |

Bizet | 5 | 3 | 2 | 5 |

Debussy | 4 | 2 | 2 | |

Einem | 12 | 3 | 1 | |

Giordano | 1 | |||

Gluck | 6 | |||

Gounod | 4 | 4 | 2 | 1 |

Janácek | 3 | 2 | 3 | |

Leoncavallo | 6 | 4 | 2 | 3 |

Mascagni | 6 | 6 | 2 | 3 |

Monteverdi | 5 | 3 | ||

Mozart | 6 | 4 8 | 7 | 6 |

Offenbach | 15 | 10 | 9 | 3 |

Orff | 2 | |||

Pfitzner | 2 | 2 | 2 | |

Puccini | 12 | 11 | 13 | 8 |

Rossini | 7 | 3 | 3 | 6 |

Shostakovich | 4 | 3 | ||

Smetana | 5 | 6 | 7 | 3 |

J. Strauss | 5 | 3 | 3 | 4 |

R. Strauss | 6 | 7 | 4 | 3 1 |

Verdi | 4 11 | 4 9 | 4 | 3 |

Wagner | 6 | 6 | 5 | 1 2 |

This is as balanced and complete a repertoire as Karajan could ever offer and in some ways bolder and more experimenting. During a comparable four-year period, 1960-1964, Karajan introduced Pizzetti’s Death in the Cathedral, Orff’s Oedipus, Britten’s Midsummer Night’s Dream, and Monteverdi’s Coronation of Poppea.

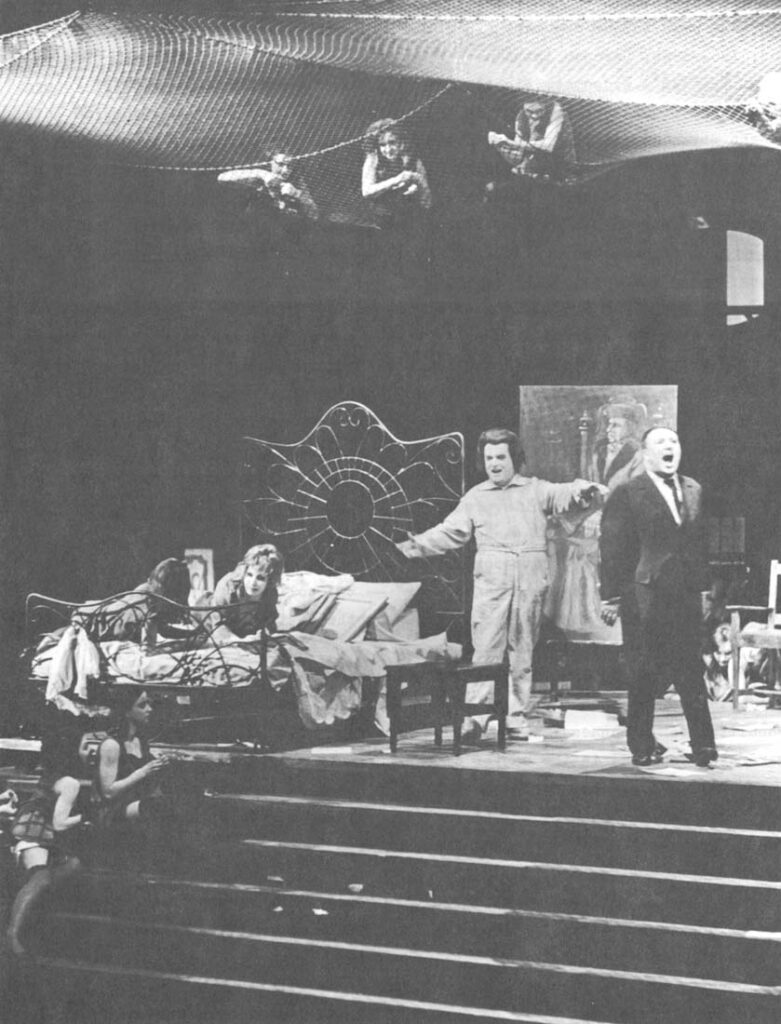

But the present management can better this during the 1966-1970 period both in modern works and in the reintroduction of unjustly neglected older opera by bringing Lulu to the Staatsoper, making Danton’s Death accepted and then shocking the Victorian Viennese by a practically topless Der Prozess, having already given a ridiculously staged but musically exciting Iphigenia, a spectacularly failing Prometheus, a somewhat superfluous Dalibor, a very necessary Silent Woman, while renewing Arabella and Katherina Ismailova.

Der Prozess (The Trial gives an erroneous impression of resemblance to Kafka) and the near-scandal around it is the most significant item on the repertoire from the point of this discussion. Its “modern” music (three decades old both in fact and in character) and “erotic” staging were roundly booed after the premiere – but it was presented! Karajan could not and did not risk such gamble because he was too much in the public eye, he was too vulnerable. The faceless and nameless management today, however, can and does try to drag the Viennese into the twentieth century while preserving the Staatsoper’s justly deserved fame for its presentation of the “standard” repertoire.

In a way then, the Staatsoper is not only able to live without Karajan, but may be better off without him or any “star” – the collective myth sustains much of its excellence even when unable to focus on the destruction of individuals who have created its institutional charisma.

It is a strange thing that – capricious or biased awarding of titles notwithstanding – the Staatsoper and the Philharmonic (see Appendix I) today are cosmopolitan yet “Viennese” while Vienna itself is without its own essence; greatness remains isolated in the center of a once-great city. An international cast and orchestra are presenting opera nightly in the best tradition of Vienna while an international audience of so-called Viennese fidgets, talks, and boos. The cohesive force of the city’s legend does not seem to be able to match that of the Staatsoper.

This was once a great city…but this still is the great Staatsoper by virtue of preserving its traditions (of the “Vienna sound”, the “stagione” system, stress on the elsewhere neglected theater aspect of opera); by being located in a tiny country willing to spend as much on it as Washington provides for all music in the whole of the U.S.; by having an institutional myth attract to it people who are able to create magic nightly; by thriving in the decay of a city that was once great.

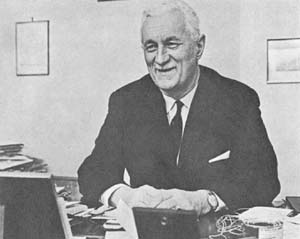

P.S.: In an age of stars, big names, charismatic personalities, it is interesting that the director of the Staatsoper, Karajan’s successor, is hardly known even in Austria, much less around the world in which Karajan is a household name. He is Heinrich Reif-Gintl who took over from Karajan’s immediate successor, Egon Hilbert, in 1968. Reif-Gintil’s term as director runs until the end of the 1971/72 season. Meanwhile, the man who has been responsible for the Staatsoper’s daily operation for the past 30 years, as directors came and went, remains firmly and effectively at his desk. His name is Ernst August Schneider and his title is Leiter des kunstlerischen Betribsburos, but what he really does is to keep the Staatsoper going, and going well, while the big names explode and flash by the horizon. Geniuses are needed to create and present great opera, but meanwhile somebody must sign the requisition forms for paper clips…

Appendix I: The Philharmonic

The single most important asset of the Staatsoper is its orchestra – an incomparable body of musicians…which is not really the opera’s orchestra.

It is called the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra, but it gives only a few concerts each year, its main work and chief purpose being the service of the Staatsoper.

It is a strange and typically Austrian setup of criss-crossing titles and functions, but it boils down to this: the members of this orchestra have historically had three distinct spheres of activity – they played every evening at the opera, they gave music lessons, and they had been giving symphony concerts on and off since 1842. The concerts were given on Sunday mornings, and later on Saturday afternoons, but never in the evening because of the obligation to the Staatsoper. It is only very seldom that functions and hats duplicate one another and that the State Opera Orchestra gives concerts in the Staatsoper as the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra…though in fact, of course, they are one and the same body. Only in Vienna…

It all started on March 28, 1842, when Otto Nicolai and Nicolaus Lenau organized a “grand philharmonic concert” with the participation of all the musicians in the various organizations of the imperial household.

The concert was a success and others followed, the third, in 1843, being the presentation of Beethoven’s Ninth which Nicolai prepared with an unprecedented – and rarely to be repeated, for any work – 13 rehearsals. Unions were rather weak then.

For the program on Nov. 28, 1847, the name “Philharmonic” appeared on posters for the first time. Around that time, Hector Berlioz heard them play during one of his visits to Vienna and wrote to a friend later:

“They are first-rate; the orchestra that Nicolai has personally built up and trained under his baton may have its equal, but it certainly has no superior. Quite apart from its accuracy, its temperament and its outstanding technical skill, it produces a wonderful purity of tone which is doubtless due to the meticulous accuracy of the instrumental tuning and to the avoidance of slipshod intonation…”

These words from a knowing and severe critic may be repeated about the orchestra today, a century after Berlioz’s encounter.

The concerts continued until 1850, lapsed for four years, were renewed by members of the orchestra, stopped again in 1857, and finally in 1860, the Philharmonic’s unbroken existence began.

Hans Richter was elected the first chief conductor by the general meeting of the Vienna Philharmonic Society and he led the orchestra for 23 years.

Mahler, director of the opera by then, succeeded Richter in 1898, and took the Philharmonic on the first of its many acclaimed foreign tours. Performing in Paris at the World Exhibition, the orchestra was given an award by the head of the exhibition’s music committee, Camille Saint-Saens.

In 1903, the Philharmonic reversed its policy of having a sole permanent conductor and issued invitations to the leading directors around Europe. Richard Strauss was one of those who responded and he maintained a life-long working friendship with the orchestra, writing some of his music for the Philharmonic.

Bruno Walter conducted the Philharmanic in 1907 for the first time, followed by such directors during the first half of the century as Fritz Busch, Otto Klemperer, Clemens Krauss, Erich Kleiber, Hans Knappertbusch, Victor de Sabata, Franz Schmidt, Thomas Beecham, Arturo Toscanini, Leopold Stokovsky, and many others.

From 1908, the Philharmonic renewed the system of having a chief, permanent conductor – a position-filled by Felix Weingartner from that year for the next 19 years. Wilhelm Furtwanglar took over in 1927, to keep the job until his death in 1954. Since then Herbert von Karajan and Karl Bohm have been the directors closely associated with the orchestra – Bohm now also in his capacity as “music director for Austria”.

Furtwängler, at the centenary celebrations in 1942, described the orchestra’s uniqueness in these words:

“It is an out and out Viennese orchestra. With very few exceptions, all its members are natives of this city; they are products of the Viennese schools of flute, oboe, and clarinet playing, the Viennese tradition of bassoon, horn, brass, percussion and string playing…The whole of this composite body of musicians, or first-class virtuoso performers, are sons of the same countryside…”

Although this is not true any more, the Philharmonic retains the “Vienna sound” and its excellence.

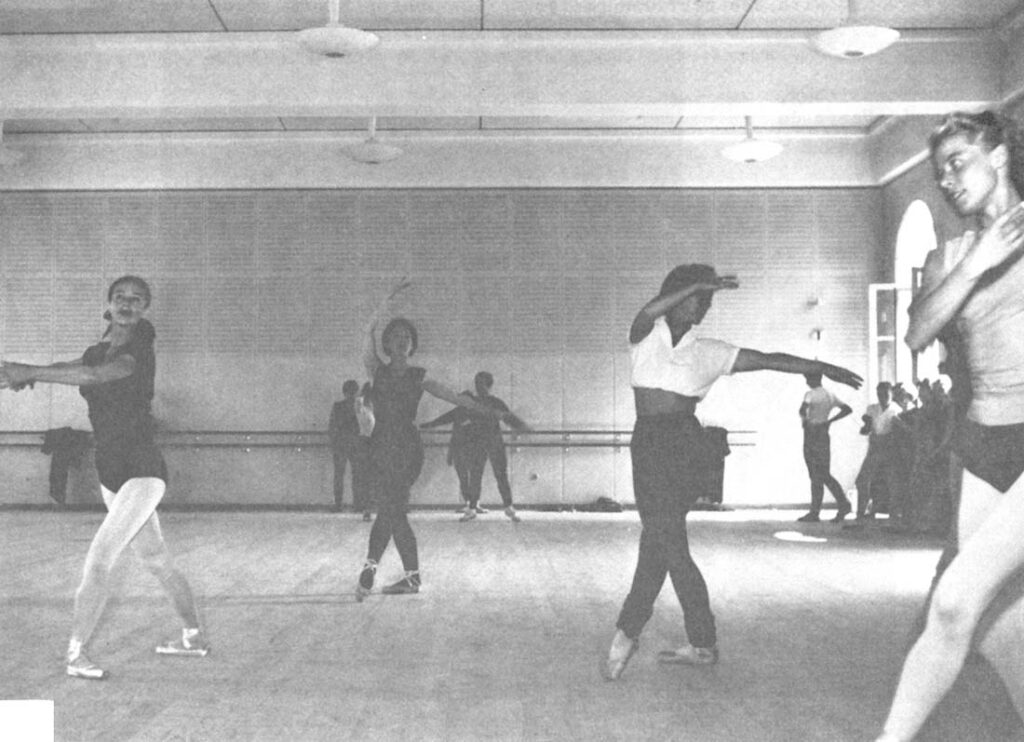

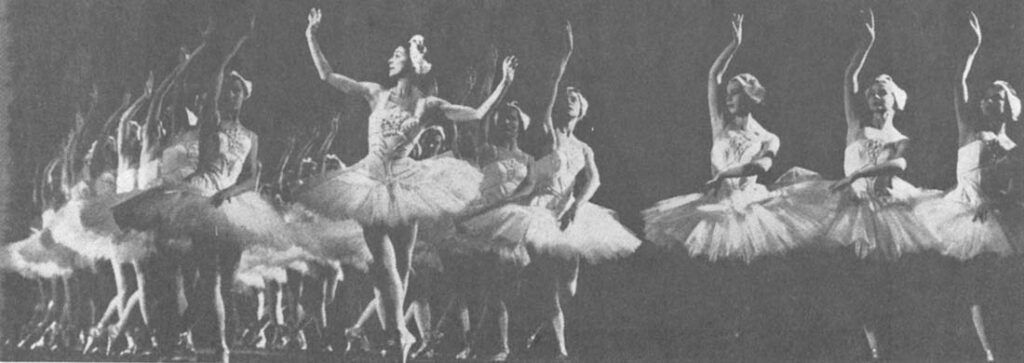

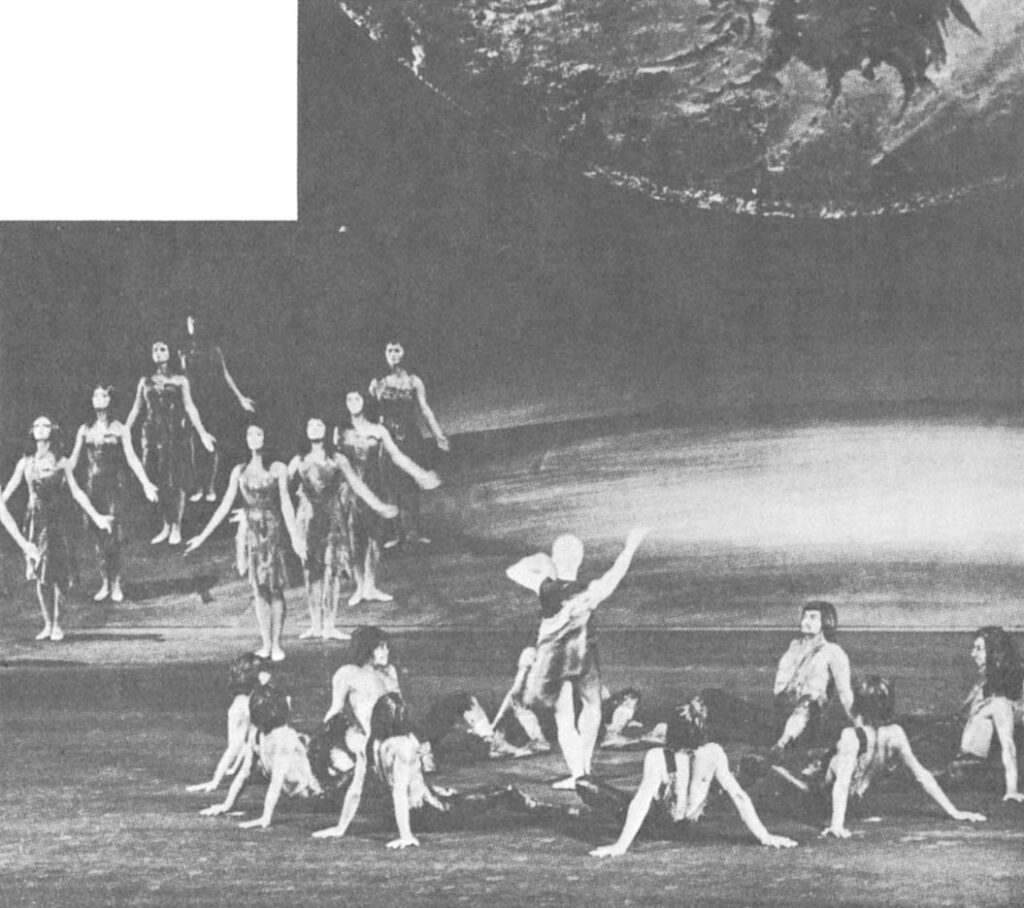

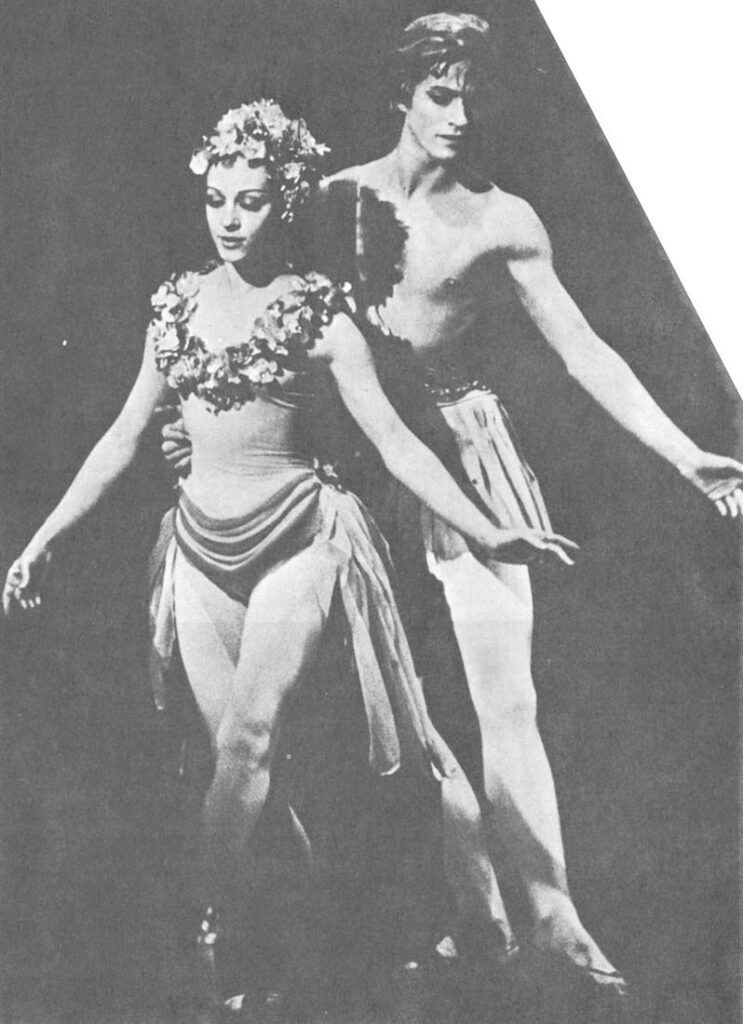

Appendix II: Ballet At The Staatsoper

From the prose of the State Press Service cultural section (responsible for publicity for all Austrian state theaters):

“The essential quality of the Vienna State Opera Ballet is brilliant technical ability flavored with Viennese charm and verve. Its exceptionally high standard of performance has nothing to do with cold perfection…”

A most clever and still courageous way to say what “outsiders” can afford to state flatly and simply: the ballet at the Staatsoper, very good as it is, does not come up to the standard of the opera itself. It serves the Staatsoper well as a part of it, but as an independent artistic body it cannot be ranked internationally anywhere near the position of the Staatsoper.

Strauss dynasty, Viennese waltz, and Fanny Elssler notwithstanding, this was always so, the ballet ending up as an appendage of the opera. True, as such an appendage, and with the services of the Philharmonic, it can reach excellence.

The reasons for excellence are known – the tradition of training ballet students in a school of its own from the age of six, working within the inspiring system of the Staatsoper – but the reasons for its inability to reach a world rank on its own are not clear at all.

After all, Vienna was one of the very birthplaces of classical ballet at the time of Gluck and the imperial court’s preference for this form of art. Later, during the second half of the 19th Century, both the world’s top ballerinas, Maria Taglioni and Fanny Elssler, danced here. Still, while the Staatsoper gains new strength from its past legends, the opera ballet cannot live up to its past brief periods of greatness.

Rudolf Klein, in his work on the Staatsoper, blames the audience:

“Ever since the days of Fanny Elssler, Viennese audiences have made no secret of their predilection for ‘divertissements.’ They find classical ballet a trifle too academic and modern ballet too intellectual.”

Yet, faced with the same weak audience, the Staatsoper can do well on the operatic field – and the ballet has problems.

Karajan tried very hard indeed and introduced 13 new ballets within four years, 1960-1964, but it took Rudolf Nureyev and Swan Lake to reach success.

The man behind the patient though unavailing attempts of the Karajan era – when ballet was introduced on a range from Prokofiev to Stravinsky, Britten, Einem, Holst, Veress – was Aurel von Miloss who, in 1962, filled the space left by the death of Erika Hanka in 1958. During those four years, the direction of the ballet strongly resembled the usual infighting at the top of the Staatsoper itself. Miloss and Vaclav Orlikovsky, ballet master since 1966, established a period of tranquility and, with dancers such as Ulli Wuhrer and Michael Birkmeyer (who took over the roles of Fonteyn and Nureyev), they may yet succeed making the Vienna State Opera Ballet an equal of the Staatsoper itself.

The same view from another angle…

From Rudolf Klein’s The Vienna State Opera:

What is of overriding importance is the element of continuity, of permanence, which alone prevents the Vienna Opera from being just another Opera House where singers show what they can do and the audience is indifferent to everything but itself. The only real danger for the Vienna Opera is a dilution of the historic substance from which it has evolved through a process of internationalization that would rob it of its individual cachet. This is not meant in any “keep out of my garden” spirit: that would be going to the opposite extreme of provincialism. What is needed and desirable is a compromise between the two extremes.

“Tradition is an excuse for slovenliness” was a favorite saying of Gustav Mahler’s. By “tradition” he meant of course the complacent habit of taking refuge in experience and a feeling for style as excuses for evading innovations. There was a time when this kind of “tradition” was very much the fashion. Today of course more hard work goes into the running of the Vienna Opera than in almost any other Opera House in the world. Just as much meticulous attention to detail is lavished on the routine everyday performance as on the gala premieres. What the management aims at is the minimum of perceptible difference between one performance and the next.

As regards interpretation then the balance is nicely preserved between tradition and innovation, at any rate as far as the singers and orchestral forces are concerned. On the creative side however there is something approaching complete sterility, and not only in Vienna. Just as many operas are being written as in the old days, but hardly any of them make their way into the permanent repertoire. This is due partly to the general development of music, and partly to problems connected with receptive capacity.

There is a transition stage, a period during which a work gradually secures a foothold in the repertoire, something akin to the present position of “Wozzeck”, for instance, or the possible future position of “Dantons Tod”.

In Vienna as elsewhere there is of course a movement in favor of a greater readiness to experiment, voices that call for striking personalities, new blood, redoubled energy. Their contribution to the future of the Vienna Opera should not be underrated. But its future can only be assured by compromise, by a constant awareness of what the Vienna Opera is and always has been, what one of its former Directors called the loftiest eminence in musical Christendom.

Appendix III: Financing The Staatsoper

Opera is big business. It is also bad business. Costly beyond dreams, it can never really pay for itself. From its very beginning in royal courts, opera has always been at the mercy of charity.

The Staatsoper is no exception – the whole building had to be reconstructed after the war, its cavernous stage must be filled each night with very expensive solo singers, a large choir, giant ships or whole forests, 700 costumes for Carmen alone, etc.

But why bother with salary figures, budgets, subsidies? It’s all part of being ruined by the mechanically-quantitative social science methods of American universities. There was a question: what makes the Staatsoper unique? “Having money” is not really part of the answer, but one way the answer was sought was through figures and the results are presented below…although they have no relevance to the original question.

(That’s what’s wrong with social scientists stuck with computers. For the fancy counting machines, “x” must equal something or other. In equations such as the “Staatsoper’s greatness = x”, the “x” remains an unknown quantity – or rather a quality or phenomenon that cannot be quantified. So any self-respecting computer will throw up if such questions are fed into it – no wonder computer-equipped social science departments of American universities are so messy these days.)

Besides being fruitless, “scientific research” of this sort is practically impossible in Austria. In the triplication of basic bureaucratic functions, every simple question (e.g., “what’s the budget for this year?”) has at least six answers – two from each of the ministerial departments.

All these caveats are necessary in order to present the following figures because, compiled from many and contradictory sources, they must be very unreliable.

Following the total figures for all the state theaters (see explanation below) in Austrian schillings, dollar figures are given for the expenses and subsidy of the Staatsoper alone – information presented to an eagerly waiting world for the very first time!

It is the first time because no breakdown is made public for the expenses and subsidy of individual units of the state theater system – heaven knows why. And so the Staatsoper dollar figures are based only on unenlightened guesswork; thus they may be exactly correct.

What comes out of all this is twofold: first, another indication of the suspected worldwide trend of all prices going up; and, second, a vindication of the Karajan regime.

There is absolutely no break in the soaring line of expenses between 1958 and 1970 in 1965 – the first year without Karajan. Salaries continued to rise at the same rate, although Karajan was accused of excess in hiring Italian guest artists.

On the other hand, there is no change in the percentage rise of income either, after Karajan’s departure – another possible bit of food for thought, were the figures reliable and meaningful, both of which are in question.

The seemingly impossible situation in 1958 (when there was more subsidy than expense) is not explained by the various ministries but it must be the result of paying for outstanding obligations on the building itself which reopened in 1955.

Additional information about the financing the state theaters (besides the charts on the next page) comes from a different source for 1964 — the last year when separate figures were available. Being a different source, its total figures are different from the figures for the same year in the charts for totals only. For that, apologies are in order, but only with a shrug of the shoulder which says “that’s Vienna.”

One source, a Mr. Erwin Thalhammer (who became administrator of the whole system meanwhile) kept presenting conflicting figures each year in the state theaters’ annual almanac until, in the report for 1969, he contradicted himself within the same story, followed by this statement: “if 57.9 is 100% then the next year’s income of 63.0 is 139% and 1960’s 73.4 is 127%…”

Until this research was undertaken, months and months after the publication of the report, nobody questioned Mr. Thalhammer’s statement. After all, he has three titles…

Year | Total Figures For Austrian State Theaters In Millions Of Schillings | ||||||

Expenditures | % | Receipts | % | Salaries | % | State Subsidy | |

1958 | 195.8 | 100 | 57.9 | 100 | 116.8 | 100 | 197.8 |

1959 | 204.8 | 105 | 63.0 | 109 | 119.9 | 103 | 141.7 |

1969 | 227.9 | 116 | 73.4 | 127 | 135.3 | 116 | 154.4 |

1961 | 241.2 | 123 | 80.3 | 139 | 137.9 | 118 | 160.9 |

1962 | 269.4 | 138 | 81.0 | 140 | 152.0 | 130 | 188.3 |

1963 | 315.0 | 161 | 87.3 | 151 | 179.3 | 153 | 227.7 |

1964 | 339.4 | 173 | 98.3 | 170 | 199.7 | 171 | 241.1 |

1965 | 362.5 | 185 | 106.9 | 185 | 226.1 | 194 | 255.6 |

1966 | 383.0 | 196 | 115.4 | 199 | 248.2 | 212 | 267.5 |

1967 | 449.2 | 229 | 119.9 | 207 | 282.1 | 241 | 329.2 |

1968 | 465.3 | 238 | 124.6 | 215 | 291.8 | 250 | 340.7 |

1969 | 480.9 | 245 | 128.0 | 221 | 352.9 | ||

1970 | 500.8 | 256 | 130.0 | 224 | 370.8 | ||

Estimated Dollar Figures For The State Opera Only (In Millions)

Year | Expenditures | State subsidy |

1958 | 3.916 | 3.956 |

1959 | 4.096 | 2.874 |

1960 | 4.558 | 3.088 |

1961 | 4.824 | 3.218 |

1962 | 5.028 | 3.766 |

1963 | 6.300 | 4.554 |

1964 | 6.788 | 4.820 |

1965 | 7.250 | 5.112 |

1966 | 7.696 | 5.350 |

1967 | 8.984 | 6.584 |

1968 | 9.306 | 6.814 |

1969 (budgeted) | 9.618 | 7.058 |

1970 (budgeted) | 10.016 | 7.416 |

The system of financing the state theaters was born with the beginning of the republic in 1918 – before that, the court collectively and members of the nobility individually paid the bills.

The Hofburgtheater became the Burgtheater, the Court Opera the State Opera and the Administration of Imperial Theaters the Federal Administration of State Theaters, an autonomous department within the Ministry of Education – there was never a question, even right after the war, about paying for Kultur.

The subsidy for the state theaters is one of the items in the Austrian national budget, needing – and receiving almost automatically – the approval of both houses of parliament. The artistic and technical staffs of the state theaters are now civil service employees, qualified for benefits of the national health service and old-age pensions that had been operating in this country since even before the birth of the republic in 1918.

Since that post-war beginning, the federal administration doubled the number of theaters under its jurisdiction, taking over the Akademietheater in 1923 and replacing the city of Vienna as guardian of the Volksoper in 1945.

In 1964 (these are the total figures different from those on the left), the total expense of running the state theaters was 349.1 million schillings, income 91 million, and the total cost to the state (subsidy) 258.1 million.

Of the 349.1 million schillings, 177.9 million were for the expenses of the Staatsoper.

Of the total of 246.3 million for permanent staff, the Staatsoper’s bill was for 135.5 million (of which 28.8 million was for pensions).

The total number of staff employed by the state theaters in 1964 (excluding the employees of the central administration, who come under a separate budget from the Ministry of Education!) was 2,549, of whom 971 were under permanent contract (directors, artists, etc.) Of the remaining number, the Staatsoper had 513 employees costing 63.6 million schillings – a figure which also includes certain scenery and production costs!

The material costs of the theaters were 97.3 million, of which the Staatsoper had 42.4 million (of which 14.5 million was for reinvestment – a quaint category including payments for machinery repairs and guest artists…

Something called “production costs” amounted to 13.9 million at the Staatsoper, of which 12 million was paid to visiting artists, except those compensated under “reinvestment.”

Income in 1964 was 91 million, of which the Staatsoper accounted for 43.1 million. Of the total attendance of 1,750,615 (a figure for 1962 for some reason), the Staatsoper had 637,490.

It’s truly wonderful how Austria pays for its theaters (between 0.3% and 0.4% of the total budget)…if only it could account for it in one simple, consistent, and available set of figures…

Received in New York on February 11, 1970.

Mr. Gereben is an Alicia Patterson Fund award winner, on Leave from the Honolulu Star-Bulletin. This article may be published with credit to Janos Gereben, the Honolulu Star-Bulletin, and the Alicia Patterson Fund.