(Alicia Patterson Reporter, Spring 2009)

FUNAFUTI, TUVALU – Karl Tili joined the Tuvalu Philatelic Bureau in 1976, when the former Ellice Islands colony first began to produce its own stamps in the early years of self-government leading up to independence. He got to see firsthand how the stamp industry quickly established itself as one of Tuvalu’s leading sources of revenue and employment in the late 1970s and early 1980s, producing limited supplies of collectible issues for enthusiasts in some 60 countries. Before a decline in the mid-1980s, the bureau boasted dozens of employees and took up two buildings just southwest of the capital’s village center on Funafuti atoll.

The bureau’s one-floor blue building now houses just a handful of workers, while most of its sales come from standing-order accounts overseas or sales to the country’s rare visitors. Now the bureau’s general manager, Tili is hoping to change that by creating a second heyday for Tuvalu stamps. In September, he accompanied the country’s finance minister on a trip to China, where he marketed his nation’s collectibles to the world’s fastest-growing market. He’s also working with the local schools to teach Tuvalu’s youth about the industry’s heritage by organizing tours of the bureau and talks excitedly about his dream to start a program where the bureau will set aside stamp collections for young Tuvaluans as both a history lesson and an investment.

Even if he can muster the funding and resources, though, he questions whether he will be able to implement these plans before he winds up leaving Tuvalu for good. Like many of his countrymen, he is torn between trying to plan his future in this small Pacific nation while simultaneously considering when to find a new home, knowing the effects of climate change will gradually make Tuvalu uninhabitable. Three of his eight children have already migrated to New Zealand, and he says he regularly advises bureau staffers to start planning for their own departures.

“There’s a lot of things happening now, where we have to look at the next 10 or 20 years and think, what would we be like?” he says. “Do we still have enough to survive on an island like this? That’s why I encourage migration. For those who can go, go. Those who can pay for a return ticket, that’s all. It might cost 10 grand or more, depending on where you’re going and if your family’s going. But this is the time to start working on those papers, not leave it until late.”

Scientific estimates vary on exactly when it will be too late – when the worsening annual floods, erosion, salination of ground water, increased tropical storms and periods of drought will make it virtually impossible for Tuvalu’s people to survive here. But finding visual evidence that climate change is already damaging Tuvalu is not a difficult task.

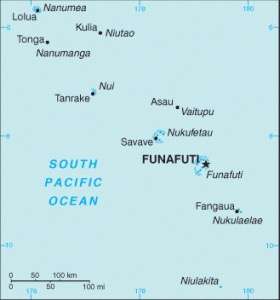

On both ends of Funafuti atoll’s Fongafale islet – the boomerang-shaped piece of land that houses about half the island nation’s population – the land is narrow enough that one can look straight ahead and simultaneously observe both the surf of the Pacific Ocean on one side and the aquamarine waters of the lagoon on the other. Piles of coral, bleached by warmer waters and still showing the detail of the organisms they once were, now form small hills along the outer edges of Fongafale.

Flooded dugouts dot the land throughout the central village Vaiaku and its surroundings. Known colloquially as the “borrow pits,” these pools date to World War II, when the American military used Tuvalu as a staging ground for attacks against Japanese-held islands to the north and excavated the pits, using the coral deposits as material to build an airstrip. That airstrip is still in use and dominates the islet’s landscape, with structures such as the national bank, soccer field and weather station built along its sides. But the Americans never returned to fill the pits, which now resemble a series of lakes – full of standing water from the ever-rising water table that sits beneath the low-lying land. Basically unusable, the borrow pits have become common sites for pig pens and waste dumping, turning into breeding grounds for mosquitoes, rats and cockroaches in the process.

Across the vast saltwater lagoon from Fongafale, Funafuti now has only a seawater-filled gap where a storm destroyed one of its small, uninhabited islets in 2005. Other areas on that side of the atoll now feature offshore palm trees with trunks surrounded by water. While the trees slowly die, they mark sites where rising Pacific tides have already carried away whole chunks of those islets.

“With the action of high seas and high level of seas, we realize now that some of the coastal lands owned by our own people are lost; they no longer exist,” says Tavau Teii, Tuvalu’s deputy prime minister and minister of natural resources. “And that is an effect. You see, we have our land system; it’s extended-family ownership. The last five years or ten years or so, there’s quite a lot of plots of land being lost. It’s being eaten away. That’s the level of the sea getting higher, as well as frequent strong winds and there’s a lot of land going into the sea.”

The reality of those impacts forces the government here, much like Tili and other businesspeople, to work simultaneously on two tracks.

In international forums, Tuvalu continues to negotiate for other countries to accept its people as migrants and to work toward recognition of its people as potential environmental refugees under international law. New Zealand currently takes up to 75 Tuvaluans a year (as well as seasonal workers), while the small island of Niue actively seeks Tuvaluan immigration and there is palpable hope that the new government of Australia will be more open than its famously anti-immigration predecessor. Tuvalu’s labor department actively encourages migration, and remittances from Tuvaluans abroad remain a major source of revenue for families here.

Of course, one problem with migration is that it further divides what is already a small population. Between 10,000 and 12,000 people currently live on Tuvalu’s nine islands – less than a third of 1 percent of even New Zealand’s population – and a number of people here express concern that migration could spell the end of Tuvalu’s distinct culture if it scatters its adherents.

“I just don’t like it because they’re driving people away,” says Silafaga Lalua, who edits the nation’s fortnightly newspaper, Tuvalu Echoes. “Of course, people have their plans and would like to go somewhere that’s more safe for their children or their families. But to me, it’s just like we are abandoning our own little island. Besides, there’s a lot of other issues that come from relocation. To me, maybe if the government invests in somewhere, buys a big piece of land somewhere and relocates the people right there to keep them together. Because the language and the culture is just going to die away, and the traditions, if people just go by themselves to wherever they want to go to.”

While actively encouraging migration, Tuvalu’s leadership is also trying to make the country habitable for as long as it can. To that end, Teii explains, the government is studying various types of sea walls to construct as temporary solutions. Already, concrete blocks line the area behind Funafuti’s main hotel, near the main jetty that locals and visitors use to enter the lagoon for swimming or boating. Past the working pier on the northern curve of Fongafale, a manmade fill connects what had once been a separate islet, providing easy road access to additional home plots, a palm-filled picnic area and what’s since become a rubbish dump on the islet’s northernmost segment.

Tuvalu’s alkaline soil makes it difficult to grow crops, and the encroaching saltwater is already damaging the staple taro and pulaka (swamp taro) crops. Root vegetables that grow in deep pits that make use of the underground freshwater table, their production is already suffering as saltwater contaminates some pits and kills the vegetables. Tuvaluans can only keep limited livestock – mostly pigs and poultry – and the expectation of prolonged droughts means those animals must compete with people for already-scarce rainwater. Tuvalu uses a filtering installation provided by the government of Taiwan to desalinate seawater for everyday use, but it has limited capacity. Other water comes in the form of bottles from Fiji, just as canned imports – primarily from Australia – increasingly make up for the shortcomings of locally produced food. Without access to recycling facilities, however, Tuvaluans send those cans and bottles into ever-growing dumps, a practice that further decreases the amount of usable land on the islands.

The reality in a place with such limited resources is that these short-term solutions can create their own long-term problems, assuming there’s even a long term here. It’s not uncommon to hear civil servants here describe in detail a program they’d like to implement before expressing doubt that funding and time will ever allow them to do so.

Even a simple plan, like Tili’s goal of creating an archive of stamp collections for young Tuvaluans, must account for Tuvalu’s precarious position.

“We want to put up one place, where there’s air conditioning, just like the post boxes they have in five-star hotels for jewelry or things that are important; then we’ve locked everything up,” he muses. “Then just before we sink, we can say, ‘Jeff or Joe Brown, you take your collection. Go to New Mexico or go to Alaska and live there. And hope and pray that the value of the thing will give you more money for your future.’”

© 2009 Jeff Fleischer

Jeff Fleischer, a Chicago journalist and author, is examining the future of the nine islands of Tuvalu as the Pacific atoll faces extinction due to rising sea tides.