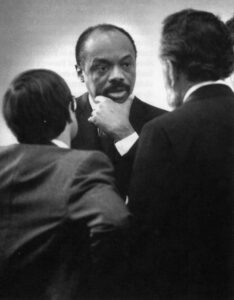

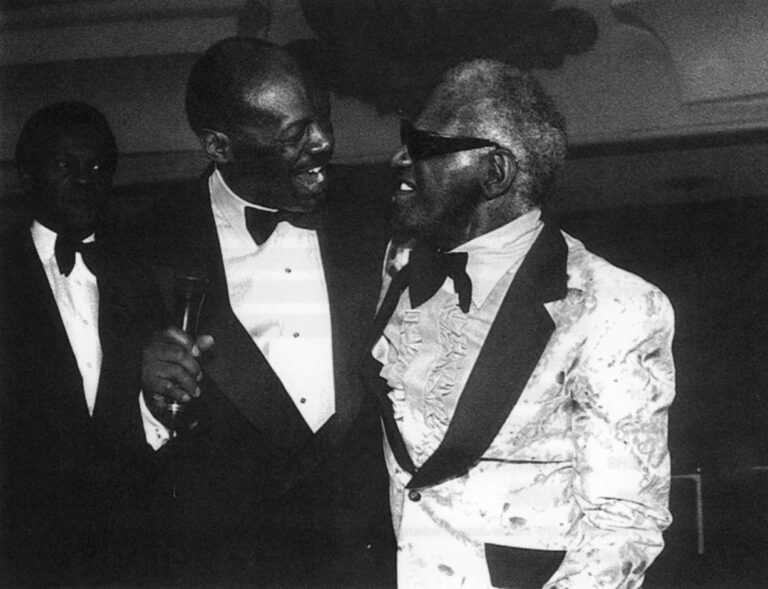

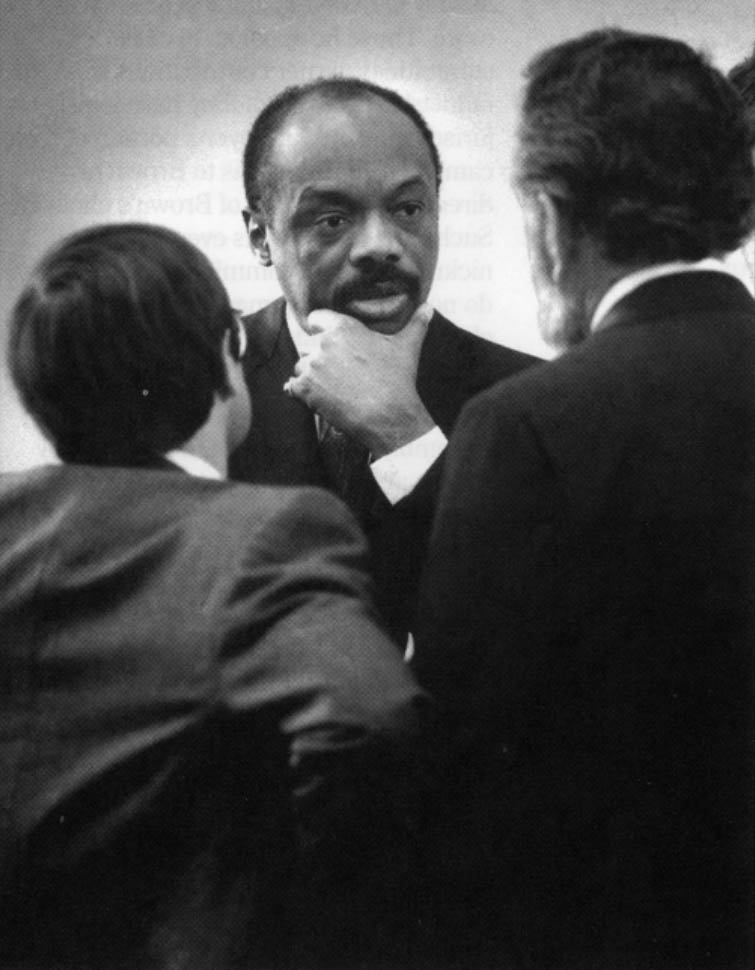

SAN FRANCISCO — Willie Brown, his tuxedo glistening in the spotlight, bounced onto a stage in the ornate ballroom of the Fairmont Hotel, the grandiose citadel of San Francisco’s old-moneyed establishment. California’s most powerful politician began introducing his after-dinner entertainment and his guests definitely would not be disappointed. On Brown’s cue, Ray Charles took stage, backed by the Oakland Symphony Orchestra.

Sitting at Table No. 55 that April evening was the mayor of San Francisco, Frank Jordan. Nearby, Brown’s night-life buddy, Herb Caen, the San Francisco Chronicle columnist, celebrated his 77th birthday over a cake given to him by Brown. Over at Table No. 84 was Marguerite Archie-Hudson, a former Brown aide and now a Democratic state legislator from Los Angeles. Assemblyman John Burton, the crusty chairman of the powerful Rules Committee, was introduced by Brown as “my oldest friend.” And mounting a run for governor, state Insurance Commissioner John Garamendi worked his way from table to table shaking hands even as Brown called forth the entertainment. “All right, John, that’s enough,” a slightly peeved Brown ordered.

Finally, the crowd settled back as Ray Charles sang “America the Beautiful.”

The paying customers under the crystal chandeliers were corporation executives, government lobbyists, union officials and trade association representatives. They paid dearly, shelling out $10,000 per table for a few hours of rubbing tuxedoed elbows with Willie Brown, the Speaker of the California State Assembly, and his friends.

Money, the mother’s milk of politics — a phrase coined a generation earlier by one of Brown’s predecessors, Jesse Unruh –flowed freely that night.

According to figures compiled by California Common Cause, Brown raked in $5.3 million during the 1991-1992 election cycle. The Republican Assembly leader, Bill Jones, was no match, raising a relatively paltry $1.2 million in the same period.

The checks written at lavish fund-raisers like at the Fairmont fuel a machine that has kept Brown in power for 13 years as Speaker, longer than anyone in California’s history.

But there is more to Brown’s power than that, much more. Brown’s grip only starts with the money that keeps his friends elected. At the heart of all Brown does is a simple maxim: keep legislative members happy.

Sacramento Bee columnist Dan Walters, among Brown’s longest standing critics, maintains that for most of his speakership “Brown functioned like a Chicago ward heeler, dispensing favors to his flock and making it clear that his continuance as Speaker and his party’s control of the Assembly were his two highest priorities.”

Assemblyman Tom Hannigan, who serves as Brown’s hand-picked Democratic Majority Leader, put it more succinctly: “If he could please your self-interest, he controlled your broader conduct.”

Brown won the speakership in December 1980 by making a deal with Republicans. Conventional wisdom held that a coalition speakership could not work and Brown would not last long, predictions that sound ludicrous in hindsight. But the conventional wisdom of 1980 was not altogether off. Brown’s grip was shaky at first. However, opportunities exploited cleverly soon steadied his hand.

Like other states in 1981, California went through a once-a-decade reapportionment of Congressional and legislative districts. Brown used the occasion to shore up his support among Democrats with a redistricting plan masterminded by his political mentor, Congressman Phillip Burton. The plan gave Democrats a lopsided advantage in California’s congressional delegation and in the Legislature. The plan also provided an escape hatch for Brown’s strongest Democratic rivals to leave the Assembly for Congress in the 1982 elections. Among those who availed themselves of the Burton-sent opportunity were Howard Berman, Mel Levine and Rick Lehman. It was Phil Burton’s final gift to Brown. The congressman died in 1983.

Brown’s skill with insider deals made him Speaker. His skill with elections keeps him there.

Election machines were supposed to be a thing of the past in California, rendered obsolete by the reform Governor Hiram Johnson in the first half of the century. Machine politics was a failing of easterners, certainly not an indulgence of independent-minded Californians.

But the politics of anti-politics is a California myth along with perfect weather and unlimited opportunity. California is periodically dominated by a strong individual, and not all of them elected. Artie Samish, a lobbyist of the 1940s and 1950s once posed for a photograph with a puppet on his knee, quipping that it was “Mr. Legislature.” He did not exaggerate his power. “Earl Warren may be the governor of the state,” Samish once remarked, “but I’m the governor of the Legislature.”

Other Assembly Speakers before Brown were adept at raising campaign funds and pushing legislation. Speaker Unruh, nicknamed “Big Daddy,” raised gobs of campaign cash and ran his machine with a collegial group of legislative colleagues nicknamed “Unruh’s Praetorian Guard.”

But no Speaker before Brown so completely centralized the campaign apparatus or made it so completely the focus of one man’s ambition. Brown has followers, but never a “Praetorian Guard.”

There is really nothing secret to Brown’s methods. He asks Democratic Assembly members with relatively safe seats to regularly ante into his election fund, usually in denominations of $10,000 or more. Those he appoints to chair committees garner contributions from the industries over which they have legislative jurisdiction and turn over a portion of their campaign contributions to Brown or directly to candidates of Brown’s choosing. Such legislative panels even have a nickname: “juice committees.” Those who do not measure up may be removed as chairmen or shifted to less potentially lucrative committees.

In 1988, for example, Democratic Assemblyman Gary Condit was fired by Brown as chairman of the Governmental Organization Committee, an innocuously named panel that presides over liquor and gambling legislation. Condit, who is now in Congress, suggested that Brown fired him because he was not leveraging enough campaign contributions. Brown countered that Condit was just a lousy chairman.

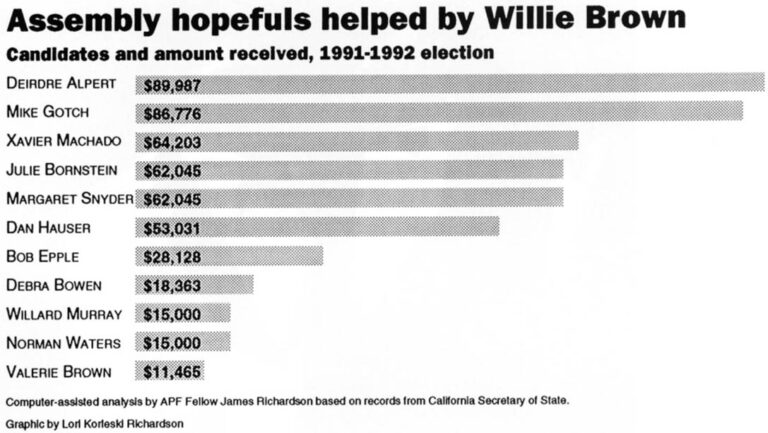

Brown dispenses campaign funds to Democratic incumbents in the most need, challengers with the best chance of bumping off a Republican or newcomers who can win an open seat for the Democrats. Costs have steadily escalated. In the 1992 elections, winning Assembly candidates received an average of $434,000, according to Common Cause.

Brown also funnels money to the California Democratic Party, which spends it on voter registration drives in targeted legislative districts. He gave $1.18 million to the party in the 1992 elections, for example. In effect, Brown is a major benefactor for the party and the party is an arm of his machine. And, he has said, he might like to head the state party once he is automatically ousted from office in 1996 under term limits.

The Speaker’s organization draws on top-flight pollsters, graphic artists, direct mail experts and campaign managers. A few, like campaign consultant Richie Ross, considered one of the most skillful in California, started with Brown’s organization. Political operatives who have worked for Brown say there is no campaign detail too minuscule for the Speaker’s interest.

The line between public service and campaign work is blurry. California taxpayers foot the $1.5 million annual bill for the Speaker’s Office of Majority Services, helping Democratic Assembly members with constituent services, public forums, press relations and other services only one step removed from actual campaigning. Majority Services also operates a state-of-the art television studio — nicknamed “WBTV” for “Willie Brown Television” — packaging video-feeds featuring Assembly Democrats for television stations.

During election years, many of Majority Services’ employees routinely leave the state payroll to join the campaigns of Democratic Assembly candidates. Gale Kaufman, director of Majority Services, is a veteran political consultant with wide experience managing numerous legislative campaigns. The state of California pays her $102,000 a year for her services to the Assembly’s Democrats when she is not working on campaigns.

The Speaker also maintains a state office in Los Angeles – 400 miles from his San Francisco district — with state-paid aides keeping contact with the varied communities of Southern California.

Los Angeles County Supervisor Gloria Molina, considered the most powerful Hispanic politician in California, is among several politicians who began as Brown aides in his Los Angeles office collecting political intelligence.

“We were gathering a lot of that information so that the Speaker would be able to, you know, enjoy the support of every ethnic group,” Molina said in 1990 for a state government oral history project at UCLA. “His goal was very clear: He intended to be Speaker for life. He wanted to make sure that his members that elected him were very happy.”

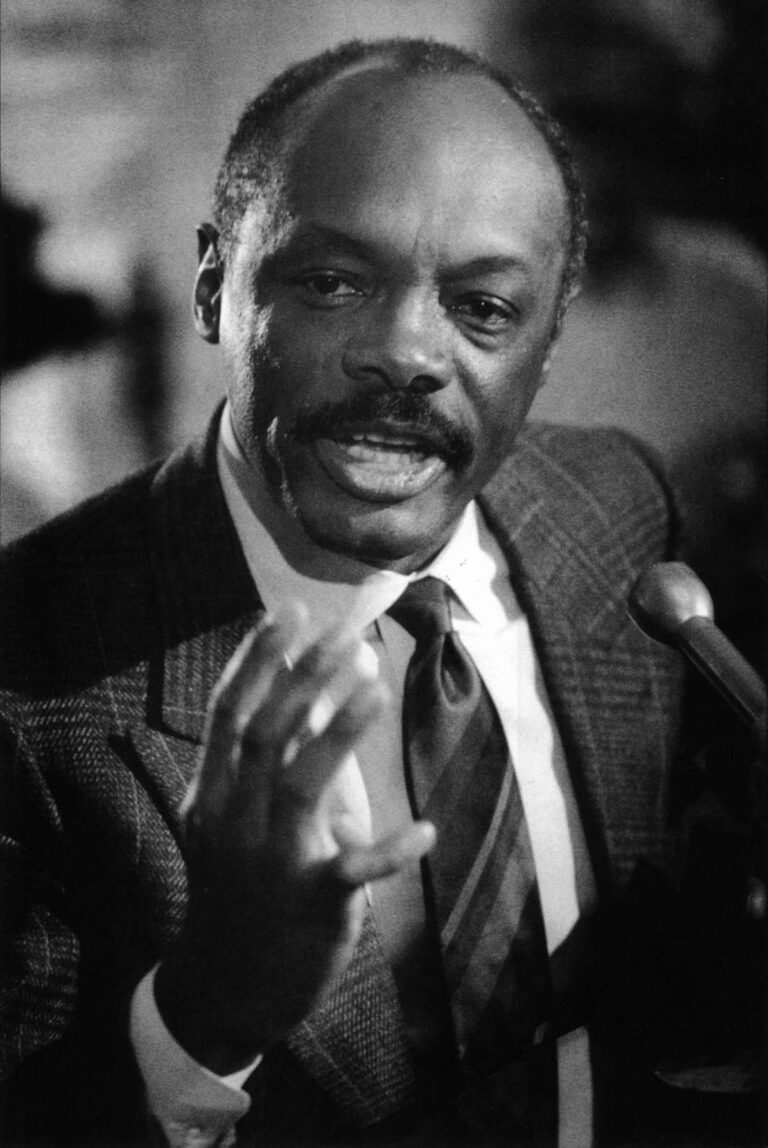

There is no job in contemporary American politics quite like that of Speaker of the California Assembly. With unparalleled authority over legislation in the nation’s most populous state, there may be no single job in America with quite as much concentrated power over the lives of so many people.

The governor can do almost nothing without the Legislature. And the governor can do almost nothing in the Legislature without the help of the Speaker.

In Brown’s hands, those powers are formidable.

“He is smarter than anyone else around,” said Democratic Assemblyman Phillip Isenberg, a former Brown aide. “At a distance all you see is Willie — the hard edges, the sharpness, and a San Francisco legislator who’s got to be a lunatic. Right? Well, you get up anywhere close to him and you understand here is a very sophisticated elected official who understands government, understands the processes, is prepared to compromise and negotiate — and to do so directly, clearly, and specifically.”

Steve Merksamer, who was chief of staff to Republican George Deukmejian, possibly the most conservative governor since World War II, counts himself as a Brown admirer.

“The Republicans have tried to sort of demonize him for political purposes — and he’s pretty easy to demonize. But the fact of the matter is the real Willie Brown is fundamentally different,” said Merksamer. “The fact of the matter is he is not, despite the conventional wisdom, a knee-jerk liberal on all the knee-jerk type of liberal issues. I found him in my experience to be a very centrist, pragmatic Democrat.”

Brown has no rival for authority over the internal workings of the Assembly. The Speaker creates committees and appoints the members to each. If it suits his purpose, the Speaker can — and will — expand or shrink the size of a committee or replace its members to obtain a desired vote on a piece of legislation.

The Speaker presides over the twice weekly sessions of the full Assembly. The Speaker’s parliamentary rulings are law.

By comparison, the upper house of the Legislature, the state Senate, is run by a five-member Rules committee, diffusing the power of the Senate’s leader, the president pro tempore.

Theoretically, the 80 members of the Assembly are answerable only to the voters from the districts they represent. But to be effective as legislators, Assembly members are very much dependent on the Speaker.

“When I first got the job, (of Majority Leader), I thought it was important to spend a lot of time with members,” said Hannigan. “I finally realized that the real heat center was the Speaker. And there’s nothing you can do to change that. If members really want something, they know where to go.”

Every legislative staff member, Democrat and Republican, is ultimately hired or fired by the Speaker. Every square inch of Capitol office space, every desk, every telephone and fax machine, every district office is assigned by the Speaker. And what the Speaker gives, the Speaker can and will take away — and give back again.

“I think Willie Brown has been speaker for 13 years because he works overtime figuring out how to retain loyalty from Democratic members,” said state Senator Patrick Johnston, a Democrat who served for a decade in the Assembly representing a Central Valley district. “Some of that is committee assignments, some of that is staff, some of that is office space, some of that where you park your car, some of that is the more personal things he does for members. He’s found doctors for some, lawyers for others. He’s done lots of things for members. I mean, he’s a `Members’ Speaker.’ “

He advices members on how to move legislation, as newly elected Democratic Assemblywoman Valerie Brown discovered. “He said call this person, this person and this person,” she recalled with amazement.

And Brown uses his legislative prowess to protect his members.

“He doesn’t try to jam us on anything that’s not good for our district,” said Democratic Assemblywoman Delaine Eastin.

For example, Brown blocked farmworker protection legislation to help Democrat Norman Waters, then the chairman of the Assembly Agriculture Committee. Waters held a seat in the scrabbled Sierra foothills that was marginal for Democrats. After several close elections, he finally lost in 1990.

Brown also keeps his members happy by serving as a lightening rod for political flak, a role often lost on governors and the public. During a record-breaking stalemate in 1992 over the state budget, Brown endured a daily drubbing from Republican Governor Pete Wilson and newspaper editorial writers. Little appreciated at the time was that Brown gave his colleagues political cover until a budget compromise could be forged.

The Speaker does favors, big and small, for his members and their families regardless of their party affiliation. Brown has lined up defense attorneys for Assembly members under federal investigation. When the daughter of Republican Assemblywoman Cathie Wright received one too many traffic tickets in 1988, Brown telephoned the judge 15 minutes before he was scheduled to take the bench. Brown asked for leniency and the judge put Wright’s daughter on probation. Distraught prosecutors later charged that Brown, who is a lawyer, acted unprofessionally.

Helping Republicans serves Brown’s broader purpose. He has always been able to rely on at least a handful of Republicans as an insurance policy for a 41-vote majority.

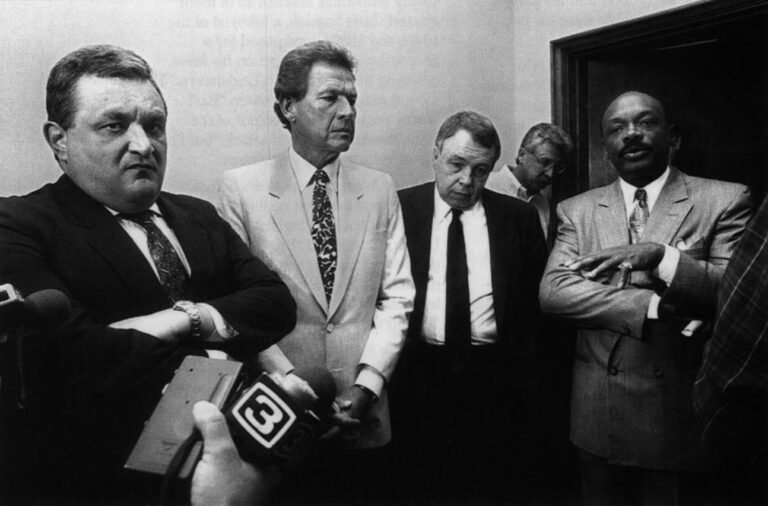

Brown needed those votes in 1988 when five disgruntled Democrats, flamboyantly dubbing themselves “The Gang of Five” (or “The Five Amigos” during more comical moments) attempted to dump him as Speaker. Among the five was Condit, the disgruntled ex-committee chairman. It was the most serious challenge Brown has faced.

The Legislature again seemed consumed by a leadership struggle at the expense of public policy.

An often overlooked factor in the rebellion were the deaths of Jesse Unruh and Bob Moretti.

The two former Democratic Assembly speakers helped Brown become Speaker in 1980 and then helped him maintain bridges to Republicans. Most important, Unruh and Moretti were among the few persons — perhaps the only persons — who could talk to Brown as a peer.

“Bob Moretti and Jess Unruh went out of their way,” said a veteran Republican Assembly member. “You need somebody that you both trust sometimes to get you back talking when you’re both angry or hurt about a situation — and Moretti and Unruh served those purposes.”

Moretti died of a heart attack while playing tennis in May 1984. “With his death we were only down to Jess,” the Republican legislator said.

Unruh, the most dominant political personality in California of his generation, died in the summer of 1987 after a battle with cancer.

That winter the “Gang of Five” rebellion exploded. Brown punished the five by stripping them of committee assignments and firing their staffs. Many thought he overreacted. It was perhaps his biggest lapse of keeping the members happy.

The five rebel Democrats eventually tried to oust Brown in a deal with Assembly Republican leader Ross Johnson, who was among the inner-circle of Republicans involved in the 1980 speakership deal. Eight years later, Johnson felt humiliated by Brown and wanted him out.

But when the votes were tallied in 1988, three Republicans defected and Republican Assemblywoman Wright, whose daughter was helped by Brown, abstained.

“Let me tell you, ladies and gentlemen, look out — I’m back,” Brown said after winning re-election as Speaker.

Johnson himself was ousted as Republican leader in July 1991. He had tried but failed in the power game against Brown. Johnson said he found the game essentially pointless. He said it was something like a popular novelty toy a few years ago.

“You push the little red button, and the top of the cube would open up and a little plastic hand would come out and curve around and push the button, the effect of which was to withdraw the hand and close the lid,” said Johnson. “That’s been the California State Assembly pretty much during Willie Brown’s term as Speaker. He has exercised power for the exercise of power. You exercise power, you raise money, and the result of that is you are able to continue to exercise power.”

While Brown’s supporters find Johnson’s observation harsh, he raises the central question of Brown’s remarkable career: Just what was his agenda beyond holding power? Was the public interest of California overwhelmed by his pursuit of power?

@1994 James D. Richardson

James D. Richardson, a reporter for the Sacramento Bee, is researching the life of Willie Brown.