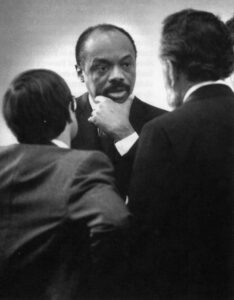

SACRAMENTO, CALIFORNIA — Willie Brown arrived to face the cameras and the questions. A new Speaker had been chosen in a closed-door meeting of Democrats in the California State Assembly and it was time to make the announcement: A liberal Democrat from San Francisco had emerged the winner.

It was not Willie Brown.

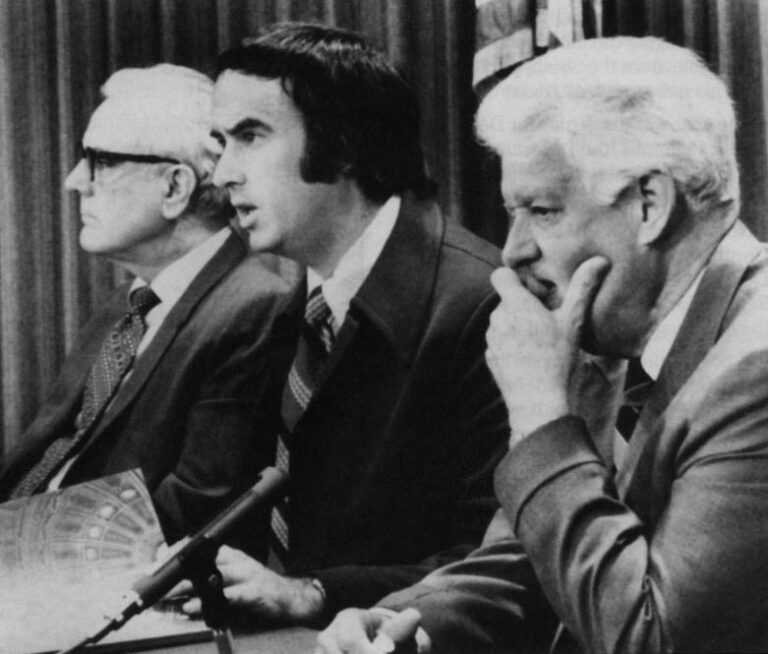

The new Speaker in June 1974 was Leo T. McCarthy, a polished, somewhat stiff, New Zealand-born lawyer representing a San Francisco district neighboring Brown’s. In California, only the governor is more powerful than the Speaker and it was a position Brown wanted dearly.

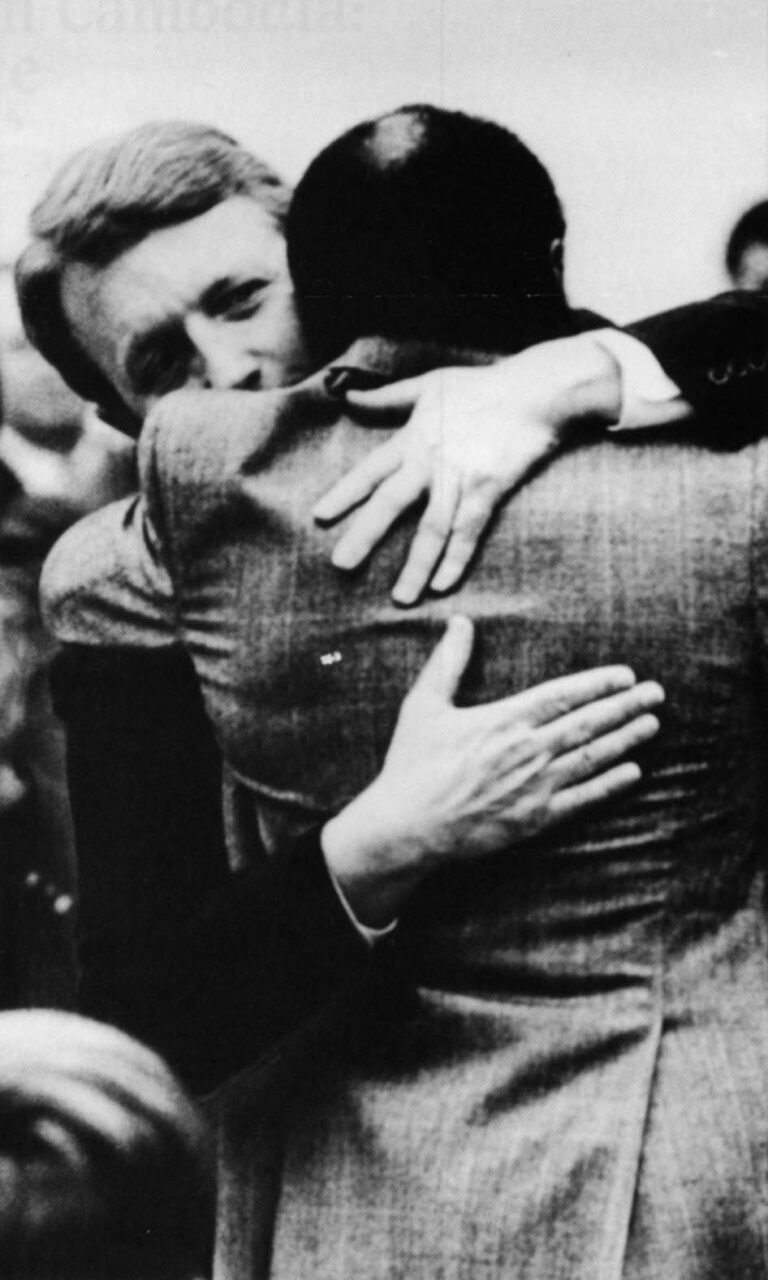

Brown and the retiring Speaker, Bob Moretti, stood with McCarthy in a show of Democratic solidarity. But it was difficult.

It was hard enough that Brown had lost, that he had failed to become the first African-American Speaker in California history. Harder still, four of the six blacks in the Assembly went against Brown and he fell short of victory by exactly four votes out of the 48 cast in the Democrats’ private meeting. Worst of all, Brown lost to McCarthy, a long-time rival of Brown and his friends, Phillip and John Burton, in the cut-throat politics of San Francisco’s Democratic Party.

The attention that day, naturally enough, was on the new Speaker. Where would he lead the Assembly? Who would he appoint to chair which powerful legislative committee?

McCarthy told the reporters he was glad the speakership fight was over. He talked of binding up “whatever wounds there must be.” He praised his rival.

But the most telling comments that day came not from McCarthy but from Brown.

“He said both of us are relieved that it is over. I am not so sure that is true,” Brown said.

The reporters laughed, accustomed to Brown’s one-liners.

“We play one more day,” Brown kept on. “There will be other days and other times and other arenas.”

For Brown, the 1974 speakership fight was only the second defeat of his life. He had lost only once before, in 1962, when he ran for the Assembly in San Francisco against a Democratic incumbent.

Brown learned from both defeats. He seldom made the same mistake twice. Six years after that most bitter of moments, Brown succeeded Leo McCarthy as Speaker — and, astonishingly, he did it with McCarthy’s help. Uppermost throughout Willie Brown’s life is a single-minded pursuit of power.

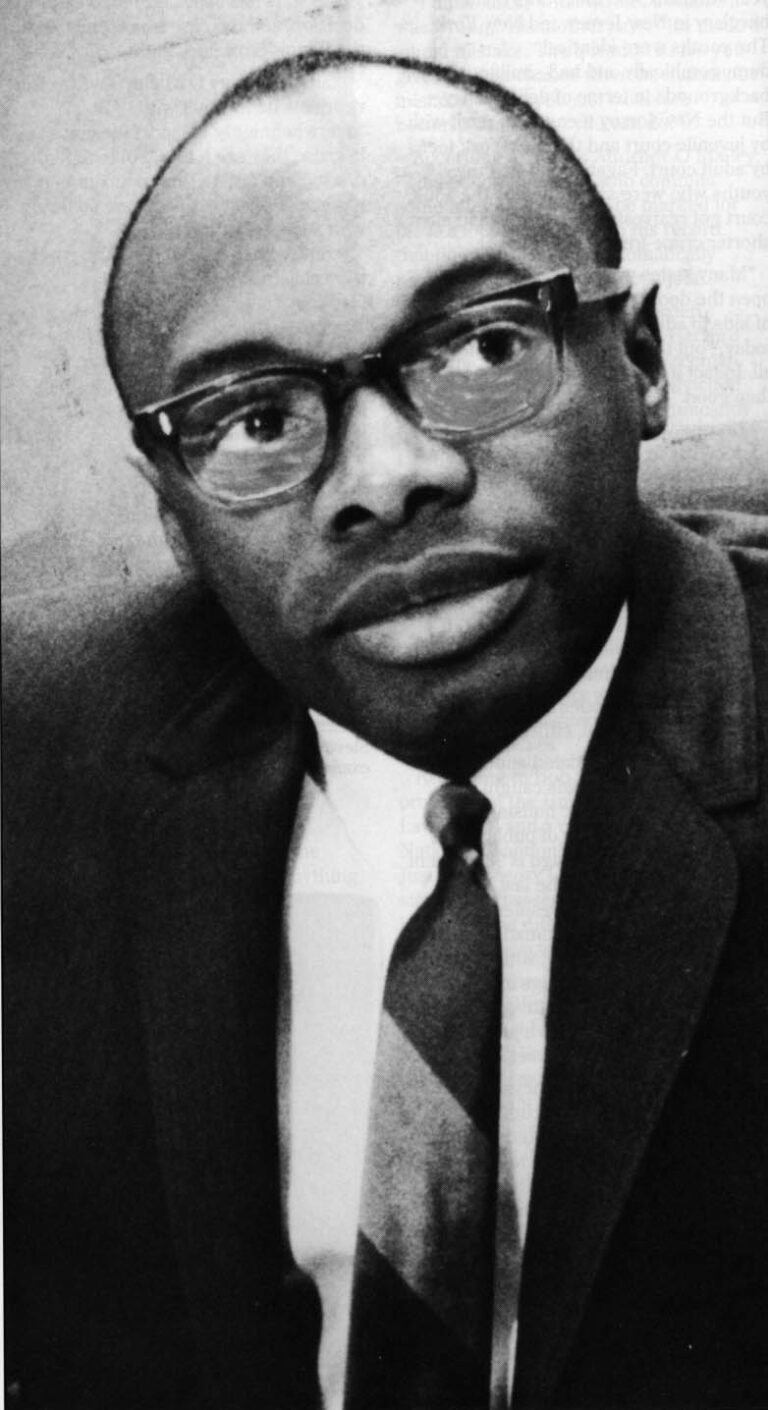

The Willie Brown who stepped off the train in San Francisco in 1951 was a serious young man. Reared and educated in an all-black segregated school in Mineola, Texas, Brown came to California looking for greater educational opportunities than Texas could offer talented blacks like himself.

Brown moved in with his uncle, Itsie Collins, the brother of his mother, Minnie. With help from a professor who recognized his talent, Brown enrolled at San Francisco State College.

Besides getting an education — an achievement in its own right — Brown’s first years in San Francisco equipped him with two pillars underpinning his future political career.

The first was his church — the black church. His mother urged him to join a church when he got to San Francisco. In his new surroundings, he soon emerged as the youth leader of the Jones United Methodist Church, a black congregation among a handful of black churches in the forefront of social activism in San Francisco.

“You see, San Francisco at time — for black people anyway — was a pioneering situation,” recalled the Rev. Hamilton Boswell, then the pastor of Jones church. “San Francisco at that time was very cruel to people, exploited them with exorbitant rents, and our church took the lead for blacks in politics and investing things in the community.”

The church gave Brown a base of votes and campaign workers. And his formidable oratorical style has remained one step removed from the black pulpit.

The second pillar of Willie Brown’s career was the Burton brothers.

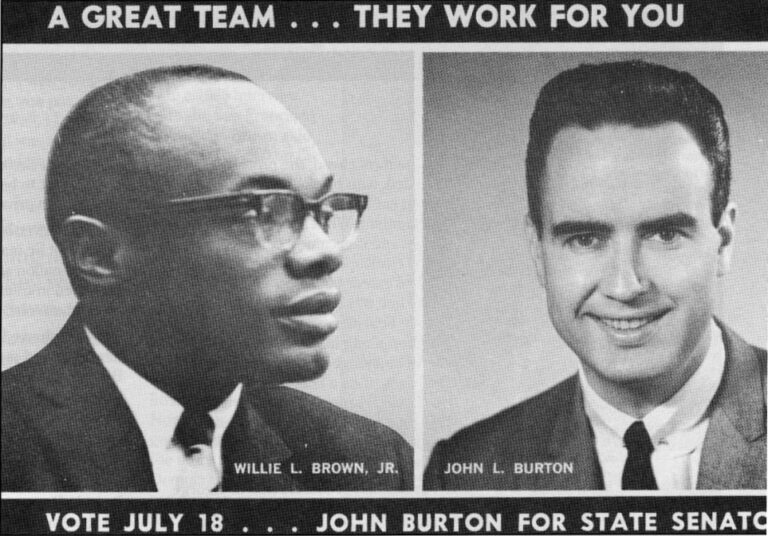

Brown met John Burton, the younger of the two brothers, at San Francisco State. Their friendship, at first glance, seemed unlikely. Burton was a white basketball player, a man-about-campus. Brown was a bespectacled, small black from a rural backwater. But both were cocky, self-assured and liberal in their outlooks. Their friendship was to deepen after college and lead them down intertwined political paths.

Brown met John’s older brother, Phillip Burton, who was elected to the Assembly in 1956 and was building a left-of-center Democratic organization challenging San Francisco’s entrenched Democratic machine. Often clad in corduroys and a red sweater, Phillip Burton was becoming well-known in the black churches.

After graduating San Francisco State, Brown went to Hastings College of the Law, a top-flight law school that is part of the University of California.

During his last year in law school, Brown married Blanche Vitero, a dance student whom he met at San Francisco State. They married in 1957 and had three children in the years ahead.

Although Brown obtained a first-rate legal education, the established San Francisco law firms were not open to blacks in the 1950s. Brown began his law practice defending prostitutes and doing legal work for his church.

Willie Brown came into the public eye by happenstance.

Brown’s wife Blanche and a friend went house hunting on a pleasant day in May 1961. When the two black women attempted to look at a model home in the Forest Knolls subdivision of San Francisco, the sales representatives quickly locked up and disappeared. It was soon clear they were not interested in showing homes to blacks, much less selling to them.

Blanche Brown returned the next day and was rebuffed again.

That Sunday, the Brown family went to church. Then 27-year-old Willie Brown led his wife, two baby daughters, and a few friends to the housing development. Brown alerted the local newspapers. Reporters were waiting when the Brown party arrived. The sales representatives again disappeared, so the Browns sat down in the garage and stayed for the day. Forest Knolls took a drubbing in the newspapers.

n the days ahead, the protest escalated, with blacks taking turns getting snubbed at the Forest Knolls development. Whites also joined the protest and it became a cause celebré in liberal circles. Among those whose political career began on Willie Brown’s picket line was a young housewife, Dianne Feinstein, who brought her daughter along in a baby carriage. Years later, Feinstein became Mayor of San Francisco, then a U.S. senator from California. Throughout her career, Feinstein enjoyed a mutually beneficial political friendship with Brown. It began at the Forest Knolls sit-in.

Finally, San Francisco Mayor George Christopher implored the housing developer to at least show a home to Brown. But Brown declined the offer: “I do not want to be an exception. I would not accept a private showing.”

Brown never bought a house at Forest Knolls but he made his point: Discrimination against blacks still was ingrained in California just like everywhere else in the nation.

Brown showed his knack at grabbing headlines and molding public opinion. But his considerable communications skill did not win the ultimate goal. It would take legislation and court cases by others to achieve open housing for blacks.

The protest had one immediate impact: It made Brown a natural candidate to run for the Assembly in 1962.

He had something else going for him. His friend, Assemblyman Phillip Burton, masterminded the once-a-decade redistricting a year earlier, shaping the 18th Assembly district in San Francisco for a black Democrat.

The seat was held by 76-year-old Democrat Ed Gaffney, a pasty-looking hack of two decades. Gaffney rested on the support of labor unions and, some said, was visibly uncomfortable with his black constituents. “He had never done a thing for us, never even visited any of us — didn’t care,” Boswell said.

Brown went after Gaffney in the June 1962 Democratic primary. The core of Brown’s campaign was the black churches with Rev. Boswell his campaign chairman. Years later, Boswell, who is now the Chaplain of the Assembly, recalled Brown’s first campaign was financed by passing a paper cup during Sunday services.

Gaffney refused to debate Brown, haughtily asserting: “Incumbents don’t debate.”

Gaffney told a legislative staffer: “I have a little “n…..” running against me. I’m going to teach him a lesson.”

Brown lost. Even so, out of 31,000 votes cast in the primary, Brown came within 916 votes of dumping the incumbent.

“I’ll never forget going to see him after that defeat,” said Boswell. “I was going to console him. I said: ‘Willie, you put up a good fight.’ And he said: ‘Well, I knew I was going to lose. But that was the first step. I’ve anticipated it.’ And he ended up encouraging me.”

Brown and the Burtons threw everything at Gaffney in 1964. They were going to take him down.

Gaffney still had respectable support. He was endorsed by Governor Edmund “Pat” Brown and Assembly Speaker Jesse Unruh, the Big Daddy Democratic boss of the Legislature.

Brown was continually tagged as “Willie Brown, Negro attorney” in the newspapers. But he did not run as a Negro candidate. He resorted to more expedient means.

Brown grabbed onto an issue — a state proposal to build a freeway through Golden Gate Park — and Brown wrapped it around Gaffney’s neck.

“Whether you like it or not, the State is pushing an ugly, sprawling freeway through your neighborhood,” Brown said in a letter to voters. “Your ‘representative’ is silent on this issue.”

Gaffney’s officious campaign pamphlets explained that Assembly members did not get to vote on individual highway projects. But that only made Gaffney sound wishy-washy.

Brown papered the district. An official-looking broad sheet titled “The Haight-Ashbury Democratic Reporter” pictured Brown in Golden Gate Park. “Brown points out path of freeway which threatens to destroy Panhandle,” the caption said.

Behind the scenes, Brown had professional help, including a pollster, Hal Dunleavy. With help from Phil Burton, Brown undercut Gaffney’s traditional base by winning union endorsements. Brown also mounted a first-rate precinct operation and a voter registration drive that netted 5,500 new Democratic voters.

In a 1965 interview with the San Francisco Chronicle., Brown said he spent $37,500 on the campaign, more than eight times as much as he had spent two years earlier.

On primary election day, Brown routed Gaffney, winning 14,308 votes to Gaffney’s 11,463 votes. The Republican nominee, Russell Teasdale, stood little chance in the November 1964 general election given the more than 2:1 Democratic voter registration margin.

Across town, John Burton ran in an Assembly Democratic primary against John Delury, whose campaign manager, attorney Leo McCarthy, accused the Burtons of “outrageous backroom politics.” The animosity would deepen.

Unruh endorsed Delury but John Burton won his primary anyway and then the general election.

That November, Willie Brown was elected the first African-American Assembly member from San Francisco.

Willie Brown and John Burton entered the Assembly together in December 1964. They promptly got themselves in trouble.

Smarting at Unruh for endorsing their primary opponents, Brown and Burton voted against Unruh for Speaker.

“I would be letting my supporters down if I voted for Mr. Unruh,” Brown explained at the time. “I do not anticipate any reprisal.”

Reprisals were swift.

Burton and Brown were consigned to tiny, windowless offices and unimportant committee assignments. The two were in and out of the legislative doghouse for the next several years.

Brown, Burton and another colleague sent a telegram in 1965 to British and French leaders asking them to mediate an end to the Vietnam War. Anti-war protests were still rare and a relatively innocuous telegram from three obscure state legislators ignited an intensive backlash. Republicans mounted recall campaigns and demanded the three be hauled up on treason charges.

The mess was embarrassing for Phil Burton, who was now in Congress.

Brown and John Burton soon apologized in private for causing any embarrassment to their Democratic Assembly colleagues. Unruh pronounced the affair over.

In an interview this year, John Burton said his brother, Phil, telephoned Democratic legislative leaders and implored them to go easy on his protégés.

John Burton disclosed one other thing about the episode: He signed Willie Brown’s name to the telegram without telling him.

“I just put his name on it — I figured he’d want to be,” said Burton. “He took all the shit and never said a word.”

Eventually, during a periodic shakeups in the Assembly, Unruh brought Brown and Burton in from the cold. The Speaker named Brown to chair the Committee on Representation that oversaw lobbyists — the “third house” that influenced legislation and dispensed favors to elected lawmakers.

Brown went at the task with a flourish. To the horror of the lobbyists, he forced them to register and report their spending habits. In later years, Brown boasted that his reforms so shook up the power structure that Unruh had to give him a better assignment.

In fact, Brown and Unruh were beginning to respect each other. Unruh is said to have told him one day: “It’s good thing you’re not white.”

“Why is that?” Brown asked.

“Because if you were, you’d own the place,” Unruh replied.

Unruh and Phil Burton joined forces in 1968 to help Robert Kennedy run for president. Willie Brown was brought in as a junior partner, named as a “co-chairman” of the San Francisco Kennedy campaign. Brown won a spot on the Kennedy delegation and, more importantly, a seat on the convention credentials committee. During the tumultuous convention, Brown played a role challenging the mostly-white delegations from the South, particularly from his native state of Texas.

The year was disastrous for Democrats. And in California, the Democrats lost control of the Assembly soon after the election.

Not wanting to be a Minority Leader, Unruh stepped aside to become the Democratic gubernatorial nominee facing Republican Governor Ronald Reagan in the forthcoming 1970 election.

Brown wanted to succeed Unruh as the Democratic Minority Leader in 1969. But when it became apparent Brown could not win, he and John Burton supported another black Democrat, Assemblyman John Miller, who was elected Minority Leader.

When the Democrats retook control of the Assembly in 1970, Miller felt he was entitled to become Speaker. But the real leader of the liberals was Bob Moretti, a Detroit-born, tough-talking assemblyman representing North Hollywood.

Willie Brown supported Moretti — and was well rewarded when Moretti won. But Miller would get his revenge.

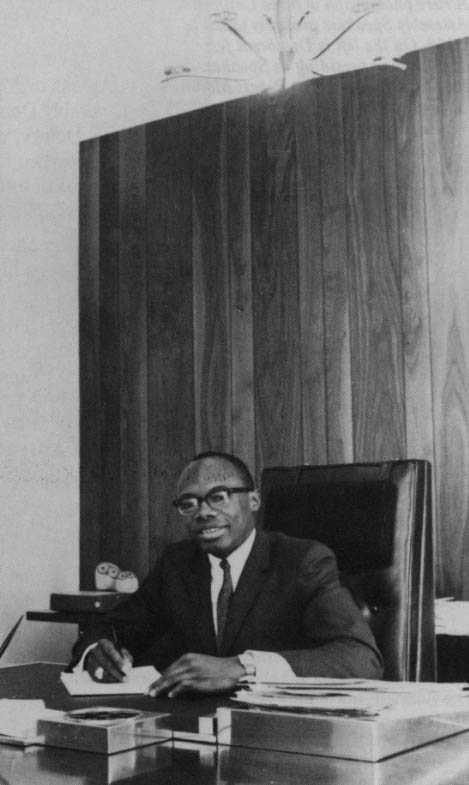

Moretti named Brown chairman of the Ways & Means Committee, considered the second most powerful job in the Assembly. Virtually every piece of legislation had to pass through the committee to reach the full Assembly for a vote.

Brown’s chairmanship was a tour d’ force. Friend and foe alike credited Brown as a brilliant chairman, perhaps too brilliant for his own good. When colleagues stepped to the podium to explain their bills, Brown sometimes cut them off and succinctly summarized the arguments for them. He often knew the legislation better than the authors. He embarrassed them.

“Once Willie became chairman of Ways & Means, he became a power himself,” said Leo McCarthy, who became lieutenant governor in 1982. “While Phil (Burton) was still acknowledged as the head of the group, Willie’s strength grew geometrically over the next several years. He ran a very, very strong Assembly Ways & Means Committee, and wielded considerable power because he was unafraid.”

Brown was now the leading Assembly Democrat in the annual negotiations over the state budget. Speaker Moretti did not care for the budget tedium.

Although drafting a state budget is stupefying in detail, nothing is more important in state government. And nothing is more political. Each year, the Senate and Assembly approved competing versions of the budget. Then three barons from each house met behind closed-doors “in conference” to draft a single budget. They practiced the grittiest, most basic of insider politics. And young, brash Brown joined the club.

“These were heavy-duty old-time legislators,” explained Phillip Isenberg, who was Brown’s chief aide at the Ways & Means Committee and is now a Democratic assemblyman. “I don’t think there’d ever been an African American in the conference committee except to serve coffee. They were surprised, very surprised.”

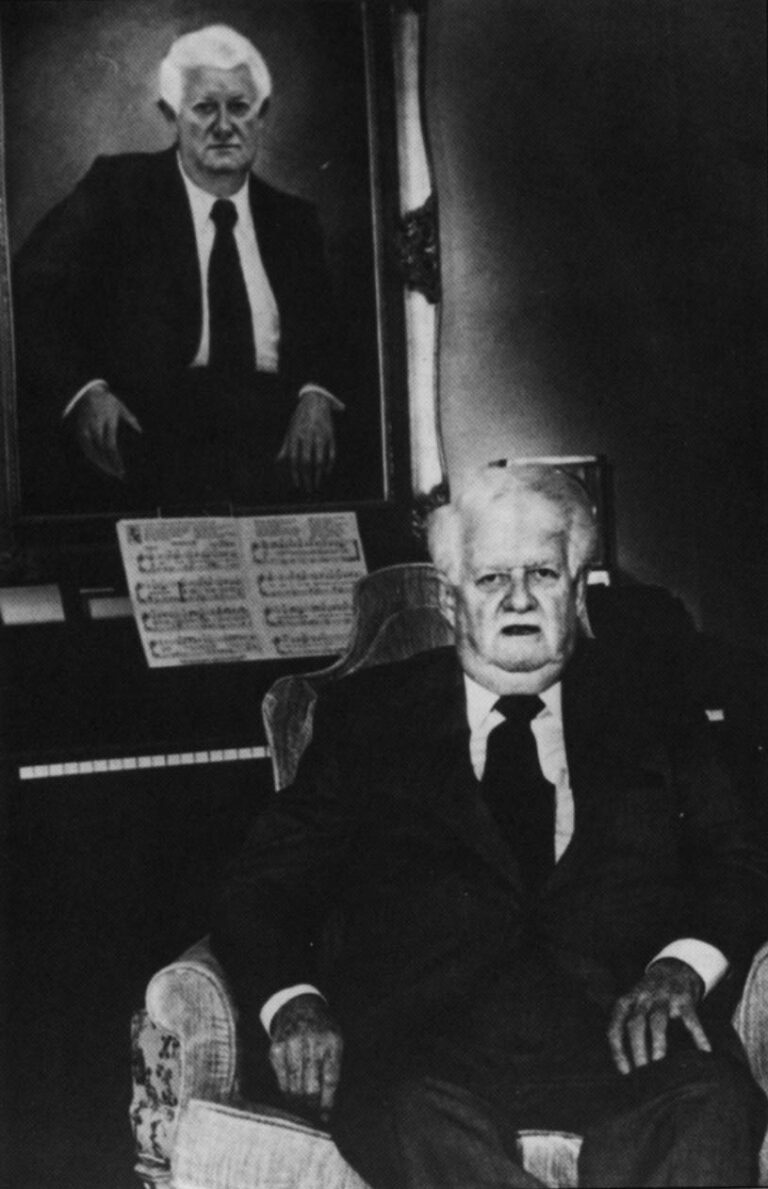

An astonishing relationship began to develop between Brown and Randolph Collier, the state Senate’s leading Democrat on the budget. The silver-haired Collier represented California’s North Coast. He was a master at winning hospitals, highways and anything else he wanted for his sparsely populated region. In the 1950s and ’60s Collier guided Governor Pat Brown’s highway building program through the Legislature and was dubbed the “father of the freeways.” Collier was close to the horse racing industry, and straddled the fence on open housing bills and other issues of importance to blacks. But he and Brown got along splendidly.

The committee met privately in a Capitol lounge where Collier stretched out on a leather sofa. Not even staff members were allowed inside except to run errands. The six lawmakers worked their way through the budget, page by page, penciling in a building here, scratching out a park there. Political careers were made and broken. Willie Brown was in his element at last.

But he was making enemies.

In 1974, the Assembly went through yet another leadership tussle. The ambitious Moretti decided to enter the Democratic gubernatorial primary and give up the Speakership. He would lose to Jerry Brown.

Willie Brown was an instant candidate for Speaker. Besides being a powerful committee chairman, Brown won notoriety two years earlier at the Democratic National Convention as a co-chairman of the California delegation pledged to George McGovern. Brown electrified the convention with a speech demanding that it turn aside a challenge to McGovern’s California delegates.

“Give me back my delegation!” Brown thundered.

“It carried the day,” McGovern said in a 1993 interview.

Brown had every reason to be confident of becoming Speaker in 1974. “I think I’ll win with no trouble at all,” he said.

But the trouble was his colleagues had a lot of grudges. Assemblyman Miller, who wanted to be the first black Speaker in 1970, was still smarting at Brown’s earlier lack of support.

While Brown boasted, rival Leo McCarthy methodically rounded up votes. With help from Miller, McCarthy won four of the six blacks in the Assembly.

By tradition, the Speaker was chosen by a majority vote of the majority party in a closed-door caucus. After the secret caucus vote, all of the members of the majority party were expected to emerge voting together in public. The tradition meant that a minority of the 80-member Assembly elected the Speaker.

In the caucus, Brown got 23 votes to McCarthy’s 26 votes. When they came out, all of the Democrats — including Brown — held to tradition and elected McCarthy.

Votes that should have been Brown’s in the Democratic caucus were not there. Howard Berman and Henry Waxman, who had been Brown’s friends since their days in the Young Democrats, voted for McCarthy.

“Willie took people like me for granted and Leo spent a lot of time working on us, talking to us, sharing his vision of how the Legislature should work. Willie didn’t pay a great deal of attention to us,” Berman said recently.

Brown also overestimated the cohesiveness of the Black Caucus. As it turned out, regional alliances were more critical. For instance, Julian Dixon of Los Angeles, now in Congress, was one of the black assemblymen voting for McCarthy. Dixon said his alliance with Berman and Waxman, who are also now in Congress, was more important than fealty to the Black Caucus.

“I had no grudge against Willie,” said Dixon.

It was now Willie Brown’s turn to taste bitterness. Despite McCarthy’s words of “binding up wounds,” he stripped Brown of the chairmanship of Ways & Means, replacing him with Assemblyman John Foran, who was McCarthy’s old law partner.

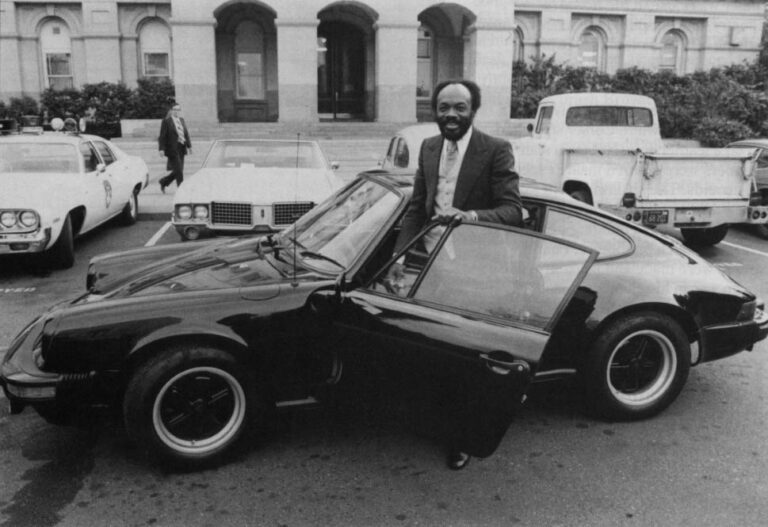

Suddenly, Brown’s upward career was headed sharply down. By his own admission, Brown tended to his Assembly duties less and less. He termed “joyless” his 1974 re-election to another two-year term in the Assembly.

“Oh God, oh boy, it was so painful,” Brown recalled recently, wincing. “It was really painful. That’s when I disappeared. I’d come up here on Monday morning for the session. I would leave promptly at noon and not return until Thursday for the session and that was it. I didn’t know any of these people, didn’t want to know any, didn’t like any of these people — considered them all awful human beings.”

Brown spent his energies building his law practice in San Francisco. He represented George Atkinson, an Oakland Raider football player, and the Joseph E. Seagrams & Sons liquor distillers. His client list began to include land developers in San Francisco. In effect, Assemblyman Brown became a City Hall lobbyist.

Brown also left the state — for a price. In 1976, he was hired by Atlantic City promoters to help convince black voters in New Jersey to approve casino gambling. He was paid $10,000, plus $2,034 in expenses.

Nonetheless, these were years of notable legislative achievements for Brown. He successfully authored legislation repealing California’s 19th Century laws against homosexuality and adultery, and fought the religious right for every inch.

It was not long before the political breeze started to blow against McCarthy and he needed to shore up his support.

In an era of inflation, home values rocketed upward and so were property taxes in California. The government in Sacramento seemed powerless to do anything about it.

Shuffling committee assignments in February 1976, McCarthy put in a call to John Burton, who by then had fled the Assembly for a seat in Congress. McCarthy asked if Willie Brown would be interested in chairing the Revenue & Taxation Committee, a post with responsibility over the tax headache.

With John Burton acting as a go-between, Willie Brown was back in a powerful legislative post.

Brown put together a property tax relief measure, backed by McCarthy. But by 1978, the juggernaut was unstoppable. The voters passed Proposition 13, a broad-brush law putting a lid on tax increases.

Assembly Democrats feared for their re-election prospects. But instead of soothing their fears, McCarthy made noises about running for statewide office. McCarthy hosted a Los Angeles political fund-raiser for his statewide ambitions. His nervous Assembly colleagues grumbled he should have been raising money for their 1980 re-election campaigns instead.

During the 1979 Christmas holiday, Howard Berman, the Majority Leader, bluntly told McCarthy to step aside and let Berman become Speaker.

“I didn’t want to be Minority Leader,” Berman said years later.

McCarthy was incensed. They argued for hours. When Berman left, he was no longer the Majority Leader. McCarthy replaced him with Brown.

The civil war among the Democrats lasted a year. The Berman and McCarthy forces targeted each other in Democratic primaries in June 1980. Each side took casualties. Republicans were no better off. McCarthy and Berman competed in trying to defeat Republicans. The bad blood spilled over into legislating in Sacramento. Each side killed the others’ bills. Finally, in November 1980, it looked like Berman had won a few more seats than McCarthy.

But the game was still very much afoot.

Unbeknownst to all but a handful of Brown’s Democratic friends — and most of them did not know all of the details — Willie Brown was negotiating with the Republicans. Horrified at the prospect of Berman as Speaker, the Republicans began to see Brown as an alternative.

Brown actually began talking with the Republicans in the summer of 1980, participants say. The talks were kept very secret. Brown, after all, was still McCarthy’s second-in-command.

There would be endless arguments in the years ahead about who agreed to what. But for now, the Republicans were satisfied.

Why did Republicans cut a deal with Brown?

“We really believed that Willie would self-destruct,” said former Assemblywoman Carol Hallett, who was the Republican Minority Leader presiding over negotiations with Brown. “We really felt that Willie’s flamboyant approach would get him into so much trouble with his own caucus that he wouldn’t last. And we were certainly wrong on that one.”

The most conservative of the Republicans had been elected two years earlier — dubbed the “Proposition 13 babies” — and they had no memory of Brown’s heavy-handedness as Ways & Means chairman. If anything, they liked his style.

Brown had one more secret weapon: Jesse Unruh.

The former Speaker was elected state Treasurer in 1974, enabling him to continue hanging around Sacramento. The gargantuan Unruh commanded a table nightly at Frank Fat’s, a popular watering hole with legislators a few blocks from the Capitol.

“Jess held court every night and didn’t care if it was a Republican or a Democrat,” said Hallett.

Unruh played a game of his own, reassuring the Republicans. He told them that Brown would be a good speaker, that he would keep his word. Unruh disliked Berman and McCarthy. Ironically, the beneficiary was Brown, whose first vote in the Assembly was cast against Unruh 16 years earlier.

By November only one thing was clear in the murky leadership struggle: McCarthy did not have enough votes to remain as Speaker. The McCarthy faction sent a negotiating committee, chaired by Brown, to seek a last-ditch truce with Berman. The talks went nowhere. McCarthy then threw his support to Brown rather than see Berman triumph. Brown’s ambitions came into the open and it soon leaked he was dealing with Republicans. It all looked more sudden than it really was.

Brown was putting the pieces together but he had one more problem. He had to break the tradition that a majority vote of the majority party elected the Speaker. He could challenge the tradition outright, or could try to win a tie vote in the private Democratic caucus so that he could use his trump card — the Republicans — in the public vote on the Assembly floor.

To get a tie vote in the caucus, Brown needed to pick up some of Berman’s Democratic votes. He started calling in old chits. The two most critical votes turned out to be those of assemblymen Richard Alatorre and Art Torres of Los Angeles, both whom went back further with Brown than they did with Berman. But the two Latinos were close to Cesar Chavez and the farm workers’ organizer vehemently supported Berman. In fact, Berman promised Torres nothing less than Majority Leader job if Berman became Speaker.

The Democrats convened in private on December 2, 1980. The vote was a 23-23 tie with one abstention. Alatorre and Torres voted for Brown. The vote opened a rift between Torres and Cesar Chavez that grew wider in the years ahead. To the end of his life, Chavez never spoke again to Torres.

Berman was in shock. The speakership fight would have to come to the Assembly floor where he was in for a bigger shock. On the floor, 28 Republicans voted for Brown, for a total of 51 votes to Berman’s 24.

“This could not happen and therefore I just assumed this would not happen,” Berman said this year, still incredulous. “What I never believed was that Willie –Willie Brown, the San Francisco liberal-left activist legislator — could get that hard-core Republican vote to go for him.”

But Willie Brown did just that. And now he owned the place.

@1993 James D. Richardson.

James Richardson is a reporter for the Sacramento Bee and is researching the life of Willie Brown.