When prayers end, commerce begins. It’s an inevitable consequence when you are part of a sea of worshippers flowing from West Africa’s holiest shrine.

The Great Mosque of Touba, 200 kilometers east of Dakar, Senegal, opens on a plaza. The plaza faces a casbah, an enormous maze of street vendors, pushcarts and canvas stalls stretching like a tent city into the desert.

The mosque is Ground Zero for a Muslim sect called the Mouride Brotherhood. First in Senegal, then throughout French West Africa, then to France itself, Mouride migrants are a conquering force. Their reach extends to Italy, Spain, Saudi Arabia, South Africa, and their newest colony, New York.

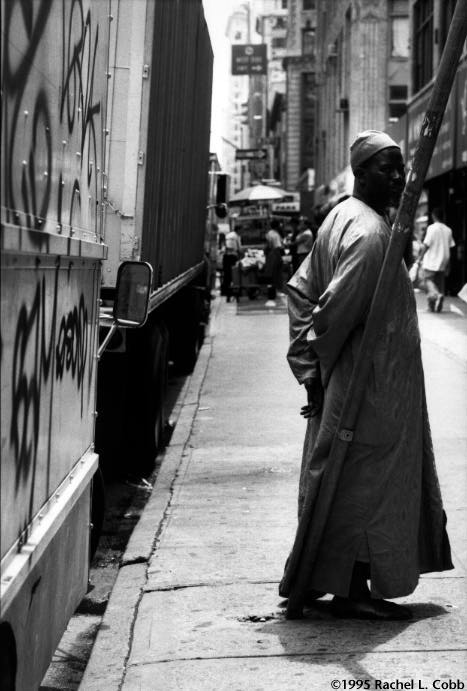

New Yorkers know Mourides as unlicensed peddlers, hovering in pairs on street corners. They deal counterfeit Rolexes from briefcases or proffer $3 umbrellas, always moments after the raindrops appear. Every couple of years, usually with an election approaching, a call rises to clear the streets of illegals. Few realize that peddlers are but the tip of a growing mass – and peddling the entry-level position – that takes Mourides into the immigration mainstream as cab drivers, restaurant workers and budding entrepreneurs.

“These Senegalese are different from all the African groups who came before,” says Sulayman Niang, a Gambian teaching African Studies at Howard University. “These are not elites, coming for college or to be diplomats, but a real community. They have a religious discipline and they are hard workers.”

It is a new phenomenon in immigration, the return of the Africans. To be sure, what preceded could scarcely be termed “immigration.” Over a span of two hundred years, the slave trade brought 20 million black Africans to the Americas, the majority landing in South America or the Caribbean. For the great “senders” of West Africa – Nigeria, Ghana, Senegal – a century passed between the end of the slave trade and the end of colonial rule. Now, a generation after independence, these countries are sending again.

Combining direct flights with those connecting through Europe, more black Africans are landing in the U.S. each week than at any time during the slave trade. Most come for short visits, but many also are choosing to stay.

The reasons for the sudden flood are spelled out in a cable prepared in 1993 for an incoming U.S. Ambassador: “Young Senegalese, whether they be urban youth, working class university students or rural-based adolescents are increasingly disaffected. Third World nationalism, creeping desertification in the North and continued decline in the economic sector have contributed to a youth movement which is increasingly frustrated and desperateA new class has emerged: the university graduate who can’t find a job.”

Compared to the English-speakers, Senegalese are stragglers. But they are leading a French exodus that is quickly catching up to the Nigerians, Ghanaians and Liberians. And they are carving their own niches in specific fields. The arc of their progress is traced in grocery delivery, giving just one example. Five years ago, all the tall black men pushing the shopping carts were from Senegal. Today they are from Mali, Togo, the Congo and Burkina Faso. Guineans have followed Senegalese into the street as peddlers; Ivorians drive gypsy cabs in Harlem and the Bronx.

Dame Babou, a Senegalese journalist who hosts a Sunday-night radio show, says perhaps 30,000 French-speaking Africans have settled in New York since 1990, the majority from Senegal. Air Afrique’s five weekly flights from Dakar to Kennedy Airport is one reason for Senegal’s dominance. Touba is another.

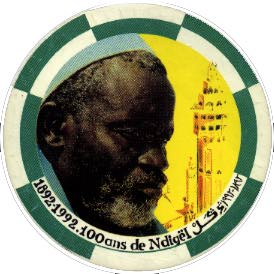

“Touba” is believed to be derived from the Arabic “ta-wa-ba” which means repentance, although Mourides everywhere insist it is Arabic for the date palm that grows in Paradise. That is not the only disagreement Mourides have with Arabic Islam. According to legend, the Wolof saint Ahmadou Bamba received a revelation there, “there” being a single baobab tree surrounded by desert. With Bamba’s blessing, an oasis grew. After Bamba died, Touba held his tomb and his mosque.

Last year, I travelled to Touba. The city lies on the edge of the great Sahelian desert, an area seared by the drought that plagued West Africa through the 1970s. Most New York supermarket boys, street peddlers and cab drivers, when asked what part of Senegal they came from simply answer “Touba.” Logically, I assumed they were refugees from economic collapse. I expected Touba to be like many “sender” villages: a wasteland surviving on exported labor.

I could not have been more wrong. Touba is one of the richest cities in West Africa, on wealth generated by trade and the alms of pilgrims. Touba confirms Mouride grace – Allah blesses those who praise Allah – in Africa’s answer to Calvin. The immigrants mean they are “of Touba,” that is, Mourides.

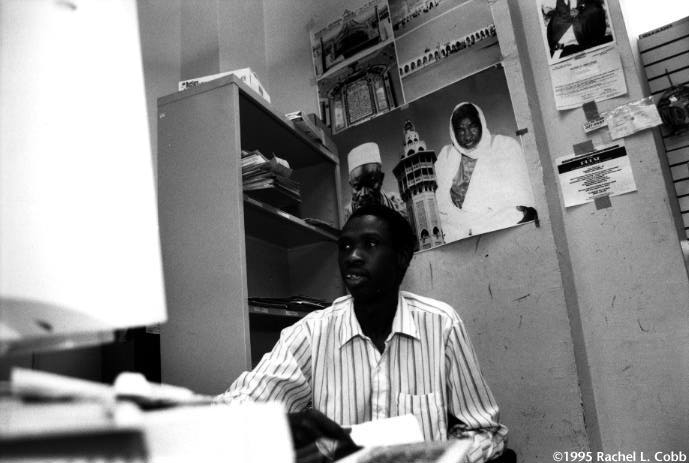

Four of Senegal’s eight million Muslims are Mourides. Their discipline and immense wealth make the brotherhood a state within a state – staffing ministries, running banks and electing presidents. Rather than fleeing religious persecution, Mouride immigrants extend an empire, colonizing new lands as effectively as the Korean, Pakistani, Jamaican and Chinese immigrants Mourides do business with in America. Some Mourides refer to migration as “jihad.” It is a peaceful campaign devoid of the Great Satan rhetoric associated with the Middle East.

Mouridism began in 1886, with the battlefield death of Lat Dior, the last Wolof king. His court, an arcane hierarchy of nobles, knights and slaves, was shattered by French rule. It reassembled in peacetime under a charismatic Muslim cleric named Ahmadou Bamba. In 1895, after exiling Ahmadou Bamba to its penal colony in Gabon, France discovered it had created a martyr. Like Iran’s exiled Ayatollah Khomeini, Ahmadou Bamba’s cult grew amid tales of his sea voyage (this, after centuries of Africans sailing away and never returning), his year praying and fasting, his emergence from incarceration with lions. He returned in 1903 and was placed under house arrest in Djourbel, a railhead near Touba.

French policy switched to accommodation, and profited from the prophet. Thousands of francs were raised from the tax disciples paid to enter Djourbel; hundreds of Wolof conscripts joined France’s World War I armies, with Bamba’s blessing. By the time Bamba died, in 1927, Mourides enjoyed a lucrative alliance with France. Touba, designated a holy city, was free from colonial rule and taxes. As a duty-free area, Touba quickly became a commercial hub.

And there were peanuts, then and now Senegal’s chief source of foreign exchange. When peanut farming was extended into Senegal’s interior, France relied on Mouride chiefs to sell the program. As a colony, the peanut industry was a profitable French monopoly. Today Senegal loses money on every peanut it sells, however, because the subsidy paid farmers (to keep farming and stay out of bursting cities like Dakar) exceeds what the harvest earns on the world market. Mouride peanut brokers compound the state’s losses by using duty-free Touba as a launching pad to smuggle product to Gambia, Mali and Mauritania. Ultimately, peanuts impoverish the state but enrich the Mourides, financing imports to fill their casbah stalls. When the pilgrims come, they bless Bamba with every purchase.

Ahmadou Bamba is credited with “Africanizing” Islam, making the creed of the slaver acceptable to his quarry. In fact, Bamba’s legacy was transforming clerics, or marabouts, into rulers. Mouridism is unique in binding disciples directly to a single marabout, even to the extent of disciples pledging their children’s loyalty to children of their marabout. In other words, it’s the traditional master-slave relationship. Most Wolof are Mourides and most Mourides are Wolof, thus Mourides preserve an ancient caste system disguised as an Islamic sect.

“You ask a Moroccan? It’s not Islam,” says Moustapha El Kadaoui, Dakar correspondent for Maghreb Arabe Presse. “Take Ramadan: you fast. Here the marabout says, ‘You don’t have to. Pay me to fast for you.'”

During holy pilgrimages, called magal, as many as a million Mourides converge on Touba. They pray five times each day in the mosque, visit their marabouts then go shopping. A stereo “boom box” manufactured in China sells for $15 in Touba. Plywood imported from Brazil and cement from South Africa, religious trinkets from Mecca and Mike Tyson t-shirts stitched in Thailand crowd the stalls.

Like any under-developed economy, Senegal’s exists in a precarious balance, actually an imbalance, of surplus manpower and scarce wealth. In Touba and Dakar, commerce is characterized not by consumers shopping for merchandise, but peddlers shopping for buyers.

Every transaction sits on an immense pyramid of labor – literally dozens of salesmen deployed for every meager sale. Five or six men “sell” one radio in a casbah stall, but perhaps a dozen more chant the name of its merchant in the street. Similar redundancies are found in procuring goods, moving goods, storing goods. It is the law of physics, not economics: sales are pulled by the gravity of humanity, the inertia of a generation that can’t find a job.

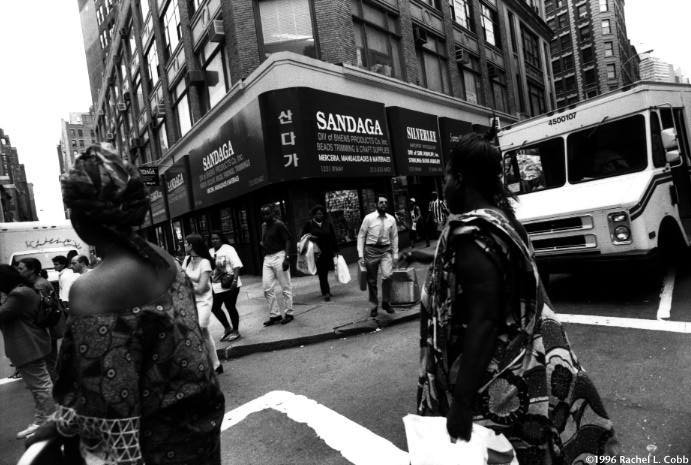

“Beugue Bamba” (Love Your Bamba!); “Wakeur Bamba” (the Followers of Bamba); “Serigne Cheikh Mbacke” (Blessed Bamba); “Cheikh Abdoulahi Mbacke” (roughly the same thing) are the names of every imaginable enterprise in Dakar’s bustling central market, the Sandaga. Fix a watch at Bijouterie Bamba, dupe a passport photo at Studio Alhamdoulahi (“thanks to God”). Taxi dashboards bear Bamba’s image; buses creak with the word “Touba” above the windshield, and “Societe Mussulmane” (Muslim, Inc.) below.

The Mosque-as-shopping-mall system works because essentially it is a slave system. The boss pledges fealty to one of the marabouts, his employees are pledged to the same marabout. They “work” unstintingly for no defined wages but are fed and housed from the boss’ pocket. Profits from the Sandaga are remitted to Touba – to build the glorious mosque but also to staff Koranic schools, provide seed and fertilizer for peanut farmers and maintain an elaborate social services network.

The system functions, too, because of a built-in safety valve: Immigration. Mourides seldom left the interior before 1965; within a generation they controlled all street commerce in Dakar. After Dakar was saturated they moved to Europe. Then came the drought in the Sahel, devastating peanut farming. In the mid-1980s, with France tightening immigration from its former colonies, Mourides targeted New York.

This new migration has both enriched the marabout and liberated their disciples. At the same time, it is reviving commerce in some of America’s poorest communities. The same “Bamba” and “Wakeur” labels, imported from the Sandaga, now are found on storefronts in Harlem and the South Bronx.

©1996 Joel Millman [This is the first of two reports]

Joel Millman is an associate editor of Forbes magazine who is researching African and Caribbean immigration.