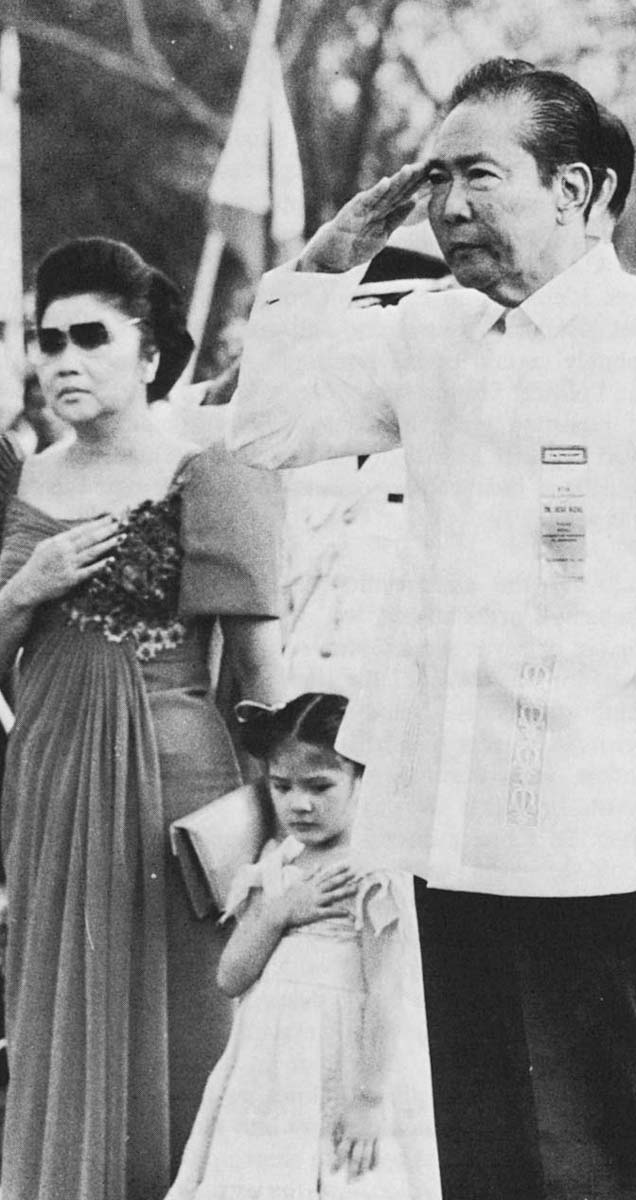

MANILA, The Philippines–When Philippine opposition leader Benigno “Ninoy” Aquino was assassinated in August, 1983, the first decision confronting the American ambassador was whether to attend mass for the fallen opposition leader. President Ferdinand Marcos, in power for 18 years, made it clear that he wanted no one in the diplomatic community to appear at the mass. His Foreign Ministry sent out a circular informing all the resident diplomatic missions that their attendance at the mass would be viewed as an unfriendly act.

Ambassador Michael Armacost decided to go anyway. According to an officer in the Political Section of the embassy, he made the decision without any extensive consultation with Washington. Armacost just didn’t think attending a funeral mass had anything to do with protocol. The State Department was merely informed that the ambassador would attend the mass. It was the first overt signal to the Filipino public that the United States would no longer give Marcos unequivocal support.

In the era of instant communication, it may sometimes seem that the role of the ambassador, the man in the field, has become superfluous to U.S. diplomacy. Policy is ostensibly made in Washington. The ambassador merely executes policy. This is the conventional wisdom. It is not always so. Indeed, when a crisis occurs, Washington doesn’t know enough about local circumstances to adopt intelligent policies. Washington inevitably prefers the status quo to the unknown. It is when momentous events–a coup, a revolution, an assassination–occur that our diplomats abroad really begin to influence policy.

This was the case in the Philippines during the two-year tenure of Ambassador Armacost. The former American colony has been governed by Marcos with dictatorial powers since 1972. It was no secret that the regime had become increasingly unpopular. But when Aquino was assassinated, the ensuing political upheaval made it seem for a time that Marcos would not survive.

By the time Armacost left the Philippines to become Under Secretary for Political Affairs, the senior job in the State Department for a career diplomat, U.S. relations with Marcos had acquired a new realism. Armacost had arrived wedded to the political survival of Marcos. When he departed, his personal relations with the Presidential couple, particularly Imelda Marcos, were cold and formal. Under the pressure of events, the Ambassador had supervised a change in Washington’s policy.

Washington has one major strategic concern in the Philippines: its naval and air bases at Subic Bay and Clark Airfield. In June 1983, just a month before Aquino was murdered at Manila’s international airport, Armacost had negotiated a renewal of the lease on the two military bases. Because Washington was completely identified with the Marcos regime, the Aquino assassination jeopardized the entire American stake in the Philippines. A replay of the Iran debacle seemed to be on the agenda. There, our lack of empathy or even contact with the opposition ensured the enmity of the Shah’s successors.

This has not happened in the Philippines. The crisis is not over; Marcos has survived, but many diplomats expect him to step down by the 1987 presidential elections. But whatever Marcos does, the Filipino public’s perception of American policy has changed. America is no longer seen as capable of manipulating all events, nor, for that matter, as completely wedded to Marcos. That was not the case before the assassination.

Then, the ambassador was called by the opposition, “the American member of the Cabinet.” Armacost was dubbed by the local press as “Armaclose,” a backhanded tribute to his closeness to President Marcos. During the first year of his ambassadorship, Armacost acted as if Marcos was a permanent fixture on the political scene. The opposition was not seen, let alone heard.

And yet, when Armacost left Manila in April, 1984, his departure was publicly mourned by prominent opposition politicians. Former Filipino diplomat Salvador P. Lopez said the lanky American Ambassador had shown himself to be “sympathetic” to the “aspirations of the people for democracy.”

In the beginning, it was different. “Armacost’s first priority,” says Herbert S. Malin, a Foreign Service Officer (FSO) in the Office of Philippine Affairs at the State Department, “was establishing good personal relations with Marcos….He had about six months to read up on the Philippines, so he came out with a set of preconceptions that initially affected his decisions. He was, for instance, a little chary at the beginning of dealing too closely with the opposition.” Malin says it was only after the Aquino assassination, when the public protests against the regime spilled over into the middle classes and the business community, that Armacost reached out to make contacts in the opposition community.

“The Aquino assassination” says Malin, “brought to the fore many political forces that were simply inevitable. But they came out a lot earlier than anyone expected.”

Another high ranking officer explained that while Armacost did pay “courtesy calls” on a couple of opposition leaders when he first arrived, “the center of gravity, as such, in handling the opposition remained with the Deputy Chief of Mission (DCM) and the senior political officers.”

In an interview, Armacost would not speak on the record concerning any of the details of his tenure in Manila. But he would say, “I would like to think that I had a fair and realistic understanding of the Marcos regime when I went out there….It is not really a matter of personal views. The hardest thing for a diplomat is both to display empathy for a foreign government and people, and, on the other hand, retain the detachment you need, the hard-headed thinking necessary to advance U.S. national interest. That is what we are there for….I tended throughout my time in Manila to tell Washington what I wanted to do and simply gave them the chance to object.”

The U.S. embassy in Manila, with more than 1,500 employees, is one of the largest in the world. If Washington ever be misinformed, it would not be owing to a lack of reporters. The Political Section is usually staffed with about a dozen FSO’s and there are an equal number of economic officers. Five or six military attaches, plus a dozen non-commissioned officers, report to the Defense Intelligence Agency. There are usually about eight officers posted in the embassy from the United States Information Service. The Central Intelligence Agency probably has at least a dozen officers under embassy cover. Everything from the Veterans Administration to the Internal Revenue Service has representatives in the Manila embassy.

Every ambassador strives for a clearly defined consensus from his officers in their reporting on any particular event. “As head of mission,” says one officer in the Political Section, “cable traffic goes out under the ambassador’s name. If there are differences of opinion, well you can report the nuances. But if there were polar opposite opinions, then people back in Washington would begin to ask why the ambassador allows such disagreement.” No ambassador wants to appear incapable of forging a consensus. Thus, only before the official consensus is cabled back to Washington, is there time for airing different views. In the case of Armacost’s tenure as ambassador to the Philippines, these differences played a considerable role in how U.S. policy makers reacted to the Philippine crisis.

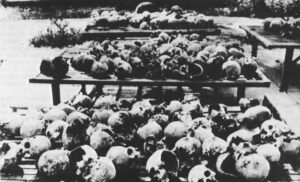

If Armacost was chary of the opposition to begin with, there were few officers who were not disillusioned with Marcos. One who had not given up on Marcos was the Consul General, the man in charge of the consular section in the embassy. “The Consul General,” says one FSO, “is known around here as the one royalist. He tries to compare the things Marcos does to the late Mayor Daley and the Chicago machine….Most of us don’t see it that way. By comparison to other countries, things are very unambiguous in the Philippines. They (the Marcos regime) are ripping off the society. They solve political problems in this country with murder.”

Some of the most astute observers of the Embassy are the Filipino businessmen and politicians used as sources of information by Embassy officers. One such contact, a businessman with close family and political connections to the Marcoses, became good friends with Air Force Colonel Richard G. Woodhull, who until recently was the defense attaché in the Embassy. Woodhull was the kind of officer who spent more time with Filipinos than he did wallowing in the complacent life of the Manila expatriate community. He and his wife traveled all over the islands and even learned the local language. And according to his Filipino business friend, Woodhull knew it was a mistake to identify U.S. policy (and the Clark/ Subic bases) so closely with Ferdinand and Imelda Marcos. “He would come to me almost every week with stories about his arguments with people in the Embassy,” says this Filipino businessman. “Armacost thought for a long time that there was no alternative to Marcos, that Marcos was salvageable. Woodhull said the turning point came when Marcos shut down the only opposition publication in town, The Forum magazine. Armacost was apparently visibly upset that Marcos couldn’t tolerate even such an insignificant opposition voice as this little magazine.” That was in December, 1982.

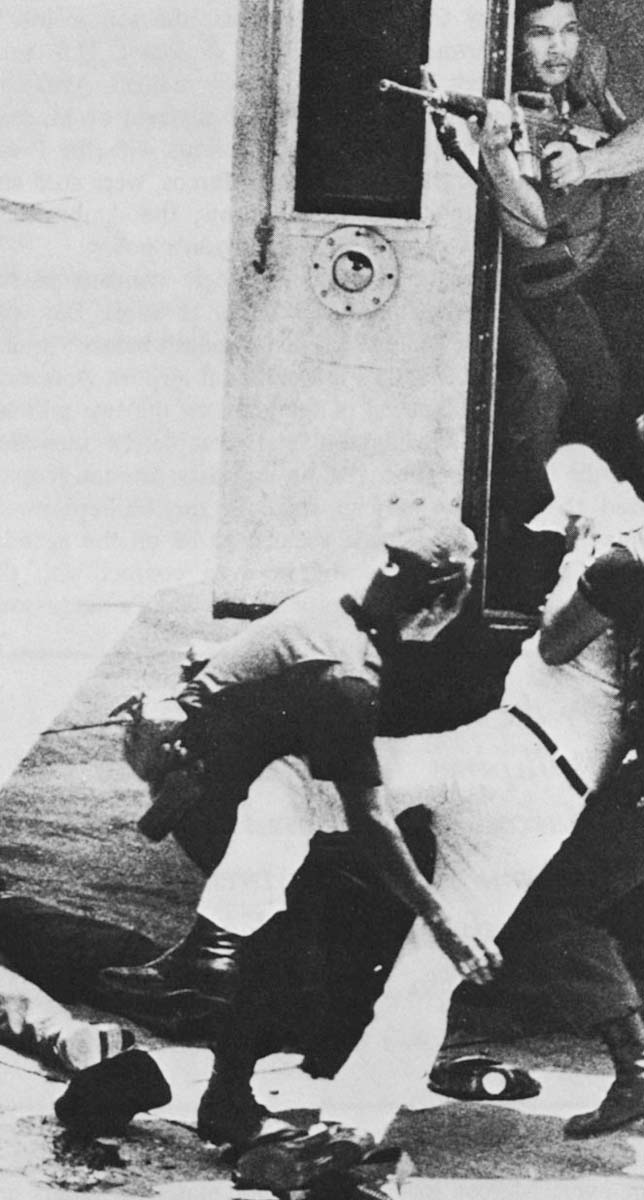

Still, no one was prepared for the public outcry and emotion-charged mass demonstrations that took place in the wake of Aquino’s assassination in August, 1983. (Aquino was shot from behind although surrounded by a military escort. The independent judicial commission investigating the slaying has virtually demolished the government’s contention that Aquino was shot by a communist hit man. The evidence now implicates the military and a group of officers close to the Presidential palace.) “Everything has changed so drastically since the assassination,” says one FSO. “Our relations with the palace have changed. But I guess the consensus inside the embassy ultimately changed when we realized how nervous the commercial banks had become.” (Hundreds of millions of dollars left the country in the wake of the assassination as local and foreign investors lost confidence in the regime.)

Another high-ranking officer said, “It was not that my opinion changed (of Marcos), but that events occurred which changed our circumstances and our reporting….The very way in which the assassination occurred mobilized sentiment that had been passive since the imposition of martial law. These were not irresponsible people. Many of them were leaders of the business community.”

Because Armacost was the only officer seeing Marcos on a regular basis, he ended up doing much of the reporting himself throughout the crisis. At times, so much was going on that the political section recruited young consular officers out on their first tour abroad to do some of the reporting.

Some sections of the Embassy over-reacted to the rush of events; many officers in the Embassy typically had criticisms of the CIA’s reporting. Theoretically, the ambassador can see everything, even raw intelligence cables, wired to Washington. But in practice, this just doesn’t happen. In the Manila Embassy there is a “reading file” available to all the political officers which does contain copies of intelligence reports. But certain of the CIA station chief’s most sensitive assessments are probably only seen by the Ambassador. Since the CIA manage the communication system utilized to send reports to Washington, they see everything their Foreign Service colleagues are reporting. “The CIA was very quick to say that things were going to hell,” says one embassy officer, “”while we only reported that things were rough.”

Washington placed more credence in the CIA’s reporting; when the State Department’s inspectors came out to Manila this spring, they complained that some officers were “wedded to a rosy picture.” Responds another officer familiar with both State Department and CIA economic reporting, “Financial information collected by covert means is worthless stuff. Everybody has to get their figures from the same public sources.”

There were also disagreements between the CIA and the rest of the Embassy staff on their assessment of the armed opposition to Marcos. The major guerrilla organization is the leftist New Peoples Army (NPA). “Much of our reporting in the political section was done just to counter what the CIA was telling Washington,” says Herb Malin, who served as political counselor in Manila for four years. Then general consensus in the embassy–the “line” that Armacost as ambassador was willing to sign his name to in reports back to Washington–today gives the NPA an estimated strength of 8,000-10,000 armed regulars. The NPA is regarded as a major irritant, but certainly incapable of toppling the Marcos regime. To be sure, some FSOs in recent years have agreed with the CIA’s pessimistic assessments. “I had one officer,” says Malin, “who came out convinced that the communist insurgency was strong and growing. He was just absolutely certain of his position.” And another officer in the Political Section said, “If the Agency is often accused of reporting every little rumor, I must admit that I’ve been satisfied with their reporting here. They have withheld from their cables some of the rumors that everyone was getting.”

“After the assassination,” says Allan Croghan, the Embassy’s press officer, “we were going around the clock for six or seven weeks. Non-stop work. We had the ambassador out there all the time making speeches and issuing statements. I had reviewed what kind of public events Armacost had been attending. Before the assassination, they were all dam openings and the like, all events in which he was identified with the Marcos regime. So I had a discussion with him and he agreed we could assign a full-time photographer to cover those events in which he would appear in non-official settings.”

By early December, 1983, the ambassador’s public speeches became implicitly critical of Marcos. “Powerful and able leaders need the discipline and they need the competition of a democratic system and a free press,” he told a Rotary Club convention in Manila. “Competitive markets and competitive politics go hand in hand.” He called for a fair judicial inquiry into the death of Aquino, and embassy officers began to show up at the public hearings of the investigation into the assassination.

If in public Armacost was pressuring Marcos by talking of democracy, in his private meetings with him the ambassador increasingly became a bearer of bad tidings. As Herb Malin said of Armacost, “He had to tell people in high places things they don’t like to hear.” About this time, William Sullivan, a former ambassador to the Philippines publicly suggested that perhaps a special envoy of ambassadorial rank ought to be sent out to read Marcos the riot act. A high official in the embassy firmly discredited the idea by saying, “The whole purpose of having an ambassadorial relationship (with a head of state) is to use it for good or bad. In the Philippine crisis, there wasn’t just one piece of bad news to convey. It was a matter of constant cajoling and obtaining progress on such issues as the financial fallout from the assassination and ground-rules for the election.”

On one occasion last autumn Marcos had to be told that President Ronald Reagan had decided to cancel his scheduled November visit to the Philippines. The formal decision to scrap the visit was made in Washington, but the embassy’s political officers were certainly opposed to the trip. “We weren’t sure how the ‘front office’ (the Ambassador) was going to come down on the trip,” said one FSO. “I know I almost considered filing a dissent cable arguing against the trip….But in the post mortem, talking to the Ambassador and the desk officers back in Washington, I don’t think there was any serious difference of opinion. We were all opposed to it.”

Soon Armacost began twisting arms. According to sources in the diplomatic community, in December, 1983 he had another private meeting with Marcos. “McCoy”–the President’s nickname–was told he must persuade Imelda Marcos to resign her position on the president’s Executive Council and issue a statement renouncing any intention of succeeding her husband into the presidency. Marcos complied with both suggestions. Imelda’s monopolistic business activities had severely antagonized the business community over the years. So both steps did much to mollify the businessmen in the Makati commercial district of Manila, the scene of repeated antigovernment demonstrations throughout the autumn.

In return, Armacost promised to do what he could to alleviate the government’s debt problems. A $200 million credit for food imports was extended through the U.S. Commodity Credit Corporation. Credits were expanded from the U.S. Export-Import Bank and disbursements were accelerated from the Economic Support Fund, which is actually the “rent” Washington pays out for use of the military bases. “It doesn’t happen that often,” says Doug Clark, an officer in the U.S. Agency for International Development in Manila, “but when an ambassador demands it, we can re-program monies originally intended for other projects. In this case, we managed to re-program $50 million in a few months to help the government with its cash flow problems.”

None of this went unnoticed by the Filipino opposition, attuned as ever to the slightest change in U.S. policy. “There’s less defense of Marcos,” former Senator Ramon Mitra said in January, 1984. “Armacost used to be a defender of Marcos. Now, I see subtle criticisms of Marcos’ policies.”

By this time, the Embassy was engaged in a tight-rope act. Armacost’s pressure on Marcos to liberalize his regime was winning it credibility with some factions of a very divided opposition. But simultaneously, the Embassy was always trying to use what new influence it had over the opposition to persuade it to participate in the May 14th assembly election. Political Counselor Scott Hallford met with church leaders in Mindanao, for instance, and in March, political officer Jim Nach arranged a meeting with a group of prominent lawyers who had decided to boycott the elections. The election, which was to be the first half-way free referendum on Marcos since 1972, could provide the government with a legitimacy it direly needed. If the opposition had to be persuaded to participate, Marcos had to be persuaded to let a good number of them win assembly seats. And lastly, Washington had to be persuaded that the liberalization policy was working.

“You have to know what phobia in Washington to address,” says Robert Rich, Deputy Chief of Mission in Manila. “If the subject is the Philippines, the first thing you get asked is, ‘Will the Philippines be another Iran?’ ” The Philippines, of course, is different in every way from Iran. But Washington feared that induced liberalization might only destabilize Marcos-just as some believe the Shah’s determination to rule was undermined by American demands for liberalization. This never seemed to be a fear of the Embassy in Manila. If anything, the Political Section under Armacost was anxious to prove that liberalization was working beyond anyone’s expectations.

On one occasion, a cable was drafted by the Political Section on the subject of press freedom. The cable asserted that the Philippines now possessed a virtually free press. Allan Croghan, a United States Information Service (USIS) officer and the embassy’s press officer, says, “There have been instances in which the Political Section has over-rated the change in press freedom….Since the Aquino assassination, there has been a change. The papers are giving space to opposition views. But there are still government controlled papers which only publish the government line.”

A recent report by the State Department’s Inspector General suggested that the Political Section ought to take more advantage of USIS knowledge and sources in their political reporting. (USIS officers handle press and cultural affairs.) “More often than not,” says Croghan, “the people in the Political Section just write something up and send it down to us to sign off on….We don’t always agree, though it is often just a matter of nuance.”

Flying Voters

Just before the May elections, a political officer drafted a cable devoted to discussing the extent of voter registration fraud. The Political Section had agreed that there were probably more than 600,000 “flying voters” (citizens who had registered at more than one polling site) registered in Greater Manila alone. “After drafting the cable,” says one officer in the Political Section, “we decided it would excite people back in Washington too much, so we decided not to do it. You don’t want to have people going over the deep end back there….We’ll report the information, but in another context. You do have to acquire a sense of management on how to convey things back to Washington.”

The elections were carried out with considerable irregularities. (In an effort to limit fraud, indelible ink to mark the finger of each voter was flown in from the U.S. in an Embassy diplomatic pouch.) In some constituencies where early returns showed the opposition far ahead, it was clear that some seats were stolen by the ruling party. This was certainly the case in the opposition stronghold of Cebu province where final results were delayed for days. Still, the results were an impressive upset; where the opposition expected to receive no more than 40 seats, the final tallies gave them 63 to the ruling party’s 109 seats. The results couldn’t have pleased the embassy more. Enough of the opposition was elected to impose some constraints on Marcos, while the elections gave the regime the degree of legitimacy it needs to last until the presidential elections of 1987. At that time, most FSO’s hope Marcos will step down.

Armacost too survived his diplomatic tightrope act, and was rewarded with a powerful new position back in Washington. His replacement in Manila, Ambassador Stephen Bosworth, announced that the US’s number one priority in the Philippines now was to help assure “an orderly transition to the next generation of responsible political leadership.” Marcos was no longer Washington’s only boy in town.

©1984 Kai Bird

Kai Bird, foreign affairs columnist on leave from The Nation, is investigating the U.S. Foreign Service.