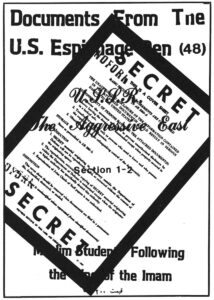

Four years have passed since the end of the 444-day Iranian hostage crisis. But if with their release, the American hostages and their long ordeal have faded from the headlines, the Iranian students still hold hostage something of great value to the American foreign policy establishment–a treasure of thousands of pages of highly classified State Department and Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) documents. And much to the embarrassment of our policymakers, the students–Muslim followers of the Line of Islam–are gradually releasing their new hostages. To date, they have published 41 volumes of “Captured Documents” found in the files of the embassy.

Four years have passed since the end of the 444-day Iranian hostage crisis. But if with their release, the American hostages and their long ordeal have faded from the headlines, the Iranian students still hold hostage something of great value to the American foreign policy establishment–a treasure of thousands of pages of highly classified State Department and Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) documents. And much to the embarrassment of our policymakers, the students–Muslim followers of the Line of Islam–are gradually releasing their new hostages. To date, they have published 41 volumes of “Captured Documents” found in the files of the embassy.

Without a doubt, this cache of classified material represents the most serious security lapse since 1962 when Kim Philby, formerly chief of British counter-Soviet intelligence, was revealed to have been a Soviet double agent. The Iranian Captured Documents divulge more about closely guarded U.S. “intelligence sources and methods” than the Pentagon Papers, which after all, were only a series of analytical reports based on access to the raw cable traffic. By contrast, the Captured Documents are themselves the rawest of classified information. One can read CIA profiles of foreign leaders, description of agents, the terms of their recruitment, and transcripts of conversations with named informants. There are long reports describing in great detail the organization and operations of other foreign intelligence services.

Surprisingly, the material is not only confined to Iranian issues. By November, 1979, the embassy files contained cables and reports dating back to the 1950’s on Iran, Afghanistan, Cuba, the Soviet Union, Lebanon, Egypt, Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, Iraq, Turkey, Israel and dozens of policy issues from nuclear proliferation to oil supplies. Much to the consternation of the U.S. intelligence community, scholars and journalists will be drawing on this material for years to come. For even if the American public has little interest in Iran at this time, there are many insights to be gathered from the Captured Documents that tell us much about how our foreign policy bureaucracy functions.

One of the most important of these is the sensitive relationship between our regular diplomats–career officers of the Foreign Service–and the intelligence bureaucracies, primarily the CIA. As displayed in the Captured Documents, that relationship is sorely strained. Foreign Service officers and intelligence officers often seem to end up undermining each other’s efforts to understand and report on what is happening to a revolutionary Iran. The classified cable traffic also suggests that the sheer number and range of highly sensitive CIA contacts and operations jeopardize the Foreign Service’s conduct of conventional, overt diplomacy. Finally, the intelligence gained from clandestine sources hardly seems to justify the risks of public disclosure.

Neither the Foreign Service nor the CIA, of course, can boast of their reporting from pre-revolutionary Iran. In mid-1978, the CIA Teheran station actually sent an overview estimate of the Shah’s stability which became known around Washington as the “all is well” cable. The Foreign Service didn’t do much better. One document, consisting of an FSO’s notes written immediately after the February, 1979 revolution, had this to say of State Department reporting: “it (the State Department) had only meager clues to the depths of Iran dissatisfaction. The few reports, hinting at severe problems, were suppressed.”

Indeed, in May, 1978 the Deputy Chief of Mission, Jack C. Miklos, blithely reported six months before the Shah fled, “Iran has now reached the position of a stable and moderate middle-level power well disposed to the United States, which has been a goal of our policy since the end of World War II.” Miklos had been stationed in Teheran since 1974, so presumably he ought to have known better. There were some officers, such as Andrew Kilgore, who reported in the early 1970’s that the Pahlevi regime was in trouble. Kilgore says he was told to cut the criticism and cease his contacts with the opposition.

Writing to a colleague on Christmas Eve, 1978, Ambassador William Sullivan admitted that “the Embassy’s access to dissident groups, particularly in the bazaar and among the religious” had been a problem. “I still, of course, remain frustrated in some measure about our inability to comprehend everything that makes these people tick, but at least in these days we do not lack voluble expressions of their often illogical viewpoints.”

Likewise with the CIA, there were undoubtedly Agency analysts who thought it unwise for the U.S. to so closely identify itself with Pahlevis. But analysts rarely visit the country they are analyzing, and are generally forced to rely on the reporting of the “collection operatives” in the field. In the case of Iran, because the CIA had been so intimately involved during the 1950’s in setting up the Shah’s intelligence apparatus, the CIA relied on SAVAK for much of its reporting on the opposition.

Even when the embassy systematically began to seek out contacts with the opposition sometime in 1978, Foreign Service officers found their possible sources of information extremely suspicious. One officer reported that “continuing charges that U.S. and CIA are meddling in Iran have significantly increased fear of being seen with or talking to embassy officers to the point where it is impairing our efforts to acquire information.” A May 8, 1978 memorandum recounts a meeting FSO John Stempel had with Mohammed Tavakoli, an aide to Mehdi Bazargan, a leading opposition figure who would eventually become Prime Minister. Tavakoli and his associates were eager to talk to embassy officers, “but have the usual paranoia about the CIA involvement.” At one point in their conversation, Tavakoli then asked if Stempel had some way of proving he was a State Department officer and whether he would mind his name being checked with Professor Richard Cottam. (Cottam, ironically enough, is a respected university professor who briefly worked for the CIA in the 1950’s and was known as a critic of U.S. policies in Iran.) Stempel readily agreed to any check that Tavakoli wanted to make and suggested that he or his friends could begin with the State Department (Biographic) Register.

Stempel was correct at the time. Checking with the publicly available Biographic Register, published by the State Department, used to be a reliable way of determining whether an individual was not a CIA officer. But after the bi-monthly Covert Action began using the Register to help determine who was a CIA agent, the State Department classified the document. Now it is impossible for FSOs to themselves be distinguished, even in such a discreet fashion, from their intelligence colleagues.

The Foreign Service very grudgingly provides CIA officers with cover jobs inside the embassy. According to the documents, the Teheran embassy just prior to the November, 1979 hostage taking, had four CIA officers who were provided with covers as first or third secretaries. What were these officers doing in the post-revolution period? And who were their sources of information?

Among other things, we know from the Captured Documents that the Agency was anxious to rebuild its network of local agents, many of which had been destroyed during the revolution. Sources on the Muslim Shiite community throughout the Arab world were a top priority. All sorts of people were recruited: a Jewish magazine publisher, code-named SDTramp’, an exiled businessman who had once been convicted of raping his niece, an American posing as a Belgian businessman, and a newspaper publisher who attended meetings of the Revolutionary Council, code-named SDLure/1. These agents were paid remarkably little, some as little as a few hundred dollars a month.

The documents on one agent, SDSlippery/1, are particularly instructive of the limits of clandestine intelligence. A well known Shiite Lebanese lawyer and former parliamentarian, SDSlippery/1, was recruited in Paris where he had set up a legal practice. At a time when a wave of Khomeini-inspired Muslim Shiite fundamentalism threatened U.S. influence in much of the conservative Arab world, SDSlippery/1 might appear to be exactly the kind of source the CIA needed. SDSlippery/1 had contacts throughout Shiite communities in the Arab world. He was known to be a rival of the radical leader of South Lebanon’s Shiite community, the Imam Musa Sadr who had mysteriously disappeared on a visit to Libya in 1978.

SDSlippery/1 was instructed to collect information on the Shiite community in Lebanon, the Higher Islamic Shiite Council and “Amal,” the Lebanese Shiite militia. For this purpose he was sent to Beirut with the following instructions:

“There is a virtual dearth of info on the ‘Amal,’ the Shiite paramilitary group in Lebanon. Strength, leadership, arms inventory, what support from Iran? Amal Secty/Gen was in Iran in mid-April and again in early July per press reports and met with Iranian leaders. Purpose/results of these meetings? What does S/1 (SD/Slippery/1) know about Husayni’s background and relationship with Iranian leaders? S/1’s info in Paris 11096 (a reference to a previous cable) that the Shiite force in Lebanon is paid for by the Syrians; trained, commanded and largely staffed by Palestinians is the first we have had on either Syrian or Pal(estinian) involvement. A substantive expansion of this would be very disseminable info.”

The CIA cable goes on to have SD/Slippery/1’s controllers request that he provide “background on each of its (Higher Islamic Shiite Council) members and their sympathies…Why have clergy lost influence, which is in such contrast to situation in Iran?”

In retrospect, of course, all of this information would be of critical importance to the American government three years later when U.S. Marines in Lebanon become the target of truck-bomb attacks carried out by Lebanese Shiite terrorist groups. If there is a role for covert intelligence collection, this is it.

But if SD/Slippery/1 is a reflection on the caliber of the Agency’s sources, one can understand the intelligence failure that was to come in Lebanon three years later. If SD/Slippery/1 is a rare source for the CIA on a critical topic, he is also a troublesome one. The cables at one point reflect a discussion inside the CIA as to whether he ought to be elevated to the status of a “principal agent.” How does the Agency evaluate this source? “To know SD/Slippery/1 is to mistrust him,” cables one CIA officer. His personality reminds another officer of “a once great agent, QPPush, who was universally suspected of working for the Israelis and for most of the Western powers, including US, and who finally died for it.”

Indeed, one of the Agency’s worries about SD/Slippery/1 is the report they have in their backfiles suggesting that since the early 1960’s, the man has had intelligence dealings with the British, the Lebanese, the Saudis, the Israelis, and the Yugoslavs. The Paris station chief, nevertheless concluded that none of these contacts should be considered “derogatory” in the context of the times, and that SD/Slippery/1 would be “worth a serious investment of time and money.” When SD/Slippery/1’s money demands caused headquarters in Langley, Virginia to balk, the station chief cabled, “It is reasonable for a man to ask for a fair wage for espionage and covert action services as it is for any other type of service, making allowances for the fact that spies do not pay taxes on covert income.”

Langley didn’t buy it and they decided not to make SD/Slippery/1 a “principal agent.” And the reason is instructive: a CIA officer who had served in the Beirut Embassy was aware that SD/Slippery/1 was “well and less than favorably known” among regular Foreign Service officers in the embassy who believed him to have a “rather unsavory reputation as (an) influence broker.”

Foreign Service officers don’t often have a high opinion of CIA sources. “You know,” said one high ranking FSO in an interview, “intelligence reporting relies on covert sources, and it needs to be balanced with straight reporting.” By definition, the paid informant provides suspect information.

But the distrust goes deeper than this. FSOs must constantly put up with suspicion from their own local sources that they are spies because it is known that the embassy provides Foreign Service cover to CIA officers. And yet FSOs also know that they never can have full access to the reporting filed by their CIA colleagues.

To be sure, a weekly cable log is passed around the Political Section of any embassy which contains some CIA reporting and summaries of intelligence sources. But the sources themselves are always protected. The ambassador, of course, has the right to see anything, but often is aware only of what his CIA Station Chief chooses to provide him. There are always exceptions. When he was ambassador to the Philippines from 1982-84, Under Secretary of State Michael Armacost said, “I used to see the station chief 20 times a day. They (CIA officers) worked for me, and not just in a technical sense.”

One deputy chief of mission in a Third World embassy says, “I made a point of telling the station chief, a fairly young man like myself, that I wanted the opportunity to attach written comments to all his cables back to the Agency. He had no problem with that. I would append a paragraph, saying yes, I approved of the analysis, or sometimes a cautionary note saying that we had not yet verified the information or source. It made him look good to have the charge (DCM) confirm his analysis.”

But this officer’s experience in a small embassy is probably unusual. “I’m greatly surprised,” says FSO Harry Jones, “I wouldn’t think it usual. The ambassador, of course, has the right to read what his station chief is reporting, but many ambassadors would rather just not know. And I don’t know if the deputy chief of mission has a right to see the intelligence traffic.”

One can’t know from the Captured Documents what intelligence cables the FSOs read or didn’t read. It would be safe to surmise that the career diplomats did not have access to the cables quoted above about the CIA’s Shiite source, SD/Slippery/1. And the FSOs probably did not want to know about the Agency’s operation in Paris to buy off foreign journalists for “the writing, editing and placement of articles favorable to USG (U.S. Government) interests.”

But the documents show that the FSOs were consulted by the Agency staff on some matters. Thus, in one August 10th, 1979 cable, the Paris station chief requests permission to resume contact with exiled former Prime Minister Shahpour Bakhtiar. The Station chief explains: “Bakhtiar was in witting contact with Teheran station officers during the early 1960’s. For obvious reasons, we would like to explore reestablishing contact at this time…Have informed State (Department) of our interest in contacting Bakhtiar and obtained their concurrence.” What follows are more than 50 pages of cable traffic reporting on those contacts, some of them run through Bakhtiar’s “press agent,” a man the CIA reports was convicted by the Shah’s regime of raping his niece. (We also learn that Bakhtiar political efforts to unseat Khomeini were being funded by the Shah’s sister.) These kind of details were no doubt kept from the career FSOs charged with establishing cordial relations with the Khomeini regime.

Other secrets were kept from the State Department. Some of the captured intelligence cables proved to the Khomeini regime that Iranians paid by the CIA had been running a “rat line”–an escape route–for hundreds of SAVAK intelligence officers wanted for crimes of torture and murder. This is worth some scrutiny since the revelation of the rat line undoubtedly prolonged the subsequent hostage crisis.

A September 27, 1979 cable from the Paris station chief to the CIA director reported that “SDJanus/38 said he just returned from Turkey where he helped ex-filtrate Director General of SAVAK for Teheran, General Parnianfar. SD/Janus/38 said there are still a few SAVAK officers hiding in Teheran but rat line using Kurds is still working well. He plans another trip to Turkey in several weeks.” Of course, the greatest intelligence failure is in being caught, and this is what happened when these intelligence cables were seized by the Iranians. Among other items, the Iranians even recovered fake exit stamps to be used to stamp the forged passports of local agents the CIA was ferreting out of the country. This “evidence” that the embassy was actually a “den of spies” dramatically increased the political leverage of the extremist factions surrounding Khomeini and thus prolonged the incarceration of the U.S. diplomats seized by the students.

More than anything else, one gets a sense that the Foreign Service is simply bureaucratically overwhelmed by the CIA Robert Ames, the CIA’s chief Middle East analyst before he was killed in the 1982 truck-bomb attack on our embassy in Beirut, once told a friend in the Foreign Service, “if we could, we’d bury you.” He need not have been joking: there are only 2,324 Foreign Service officers posted abroad, another 1,638 stationed in the State Department. (The Service also employs some 5,000 administrative staff.) By comparison, the CIA has a staff of an estimated 18,000. Some estimates range as high as 32,000. (The CIA is today the fastest growing agency in the U.S. government; in 1983 it enjoyed a 25 percent increase in its annual budget, which is estimated at $1.5 billion.) It is not at all unusual for the CIA to have more substantive officers, reporters, and editors, if you will, as opposed to administrative staff, than the Foreign Service has stationed in an embassy. This was true for instance in the early 1970s in India, where there were about a dozen regular FSOs stationed in the New Delhi embassy. But only seven of those officers were doing any kind of political or economic reporting, and the CIA had more than seven officers doing the same kind of reporting. Indeed, the imbalance is so great that last year the Reagan Administration surprisingly agreed to add some 600 new personnel to the State Department, several hundred of which will become political reporting officers. “David Stockman agreed to this move,” says one FSO, “as a result of our arguments that we were unfairly being outgunned by the C.I.A…It was done to prevent the slant of the government’s political reporting abroad from becoming too heavily dependent on intelligence sources.”

Given the CIA’s resources, how accurate has their intelligence been? The Captured Documents suggest they haven’t been right very often. As a rule, any intelligence organization must justify itself by being able to bring in enough accurate intelligence to offset the known liabilities of public disclosure of their covert activities. In Iran, the CIA never paid for itself. It did not predict the revolution, it failed to correctly analyze the strength of Khomeini’s theocratic constituency, and ultimately its mere presence constantly interfered with the non-clandestine efforts of our regular diplomatic corps to effect normalized relations with a revolutionary regime.

©1985 Kai Bird

Kai Bird, foreign affairs columnist on leave from The Nation, concludes his investigation of the U.S. Foreign Service.