Fred Ruskin wants thousand of acres of national forest land in Northern Arizona to build a shopping center, subdivisions and other developments that assure his family’s financial fortunes.

Most of it is desert scrub where cattle graze and people horseback ride, target practice, and hike through prickly pear cactus and mesquite.

Most of this public land also is valuable because it borders Interstate 17 or is suitable for expensive view lots in one of the fastest-growing rural counties in the nation.

In one of the largest national forest trades ever attempted, Ruskin is offering to swap more than half of the family’s Yavapai Ranch south of Seligman, a vast expanse of shrubby grazing land interspersed with ponderosa pine and alligator juniper. Some of the surrounding area is giving way to 40-acre ranchettes and he threatens to subdivide if the government won’t trade.

Like most exchanges involving public land across the nation, Ruskin and federal officials are negotiating the details in secret. Like most exchanges, it raises questions about whether taxpayers are being asked to forgo oversight and accountability for expediency and purported environmental and economic benefits. And, like most exchanges, the federal government is an enthusiastic supporter because it supposedly makes managing public land more efficient.

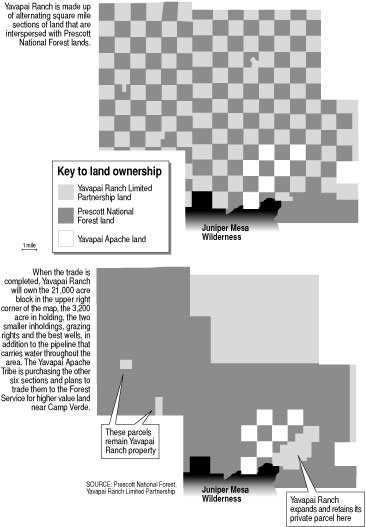

If the deal goes through, Ruskin will keep grazing rights and the best water sources on acreage he’s trading to the public — water he can use to subdivide the nearby ranch land he keeps. The Scottsdale doctor also walks away with a 3,200-acre private enclave, surrounded by the Prescott National Forest and Juniper Mesa Wilderness.

Although scarce water — the most valuable commodity in the parched Southwest — thousands of acres of public land and millions of taxpayer dollars are at stake, this transaction isn’t undergoing traditional scrutiny. Ruskin and his lobbyists are pushing this swap through Congress, bypassing public participation and environmental reviews normally required when private landowners want to trade for federally managed public land.

Ruskin acknowledges he could never accomplish the exchange without help from Congress. Instead he hammered out an initial agreement with the Prescott National Forest — which closed its Ruskin files to the public — and took it to Washington, D.C.

That’s a problem for people kept in the dark.

“We would not have known about it until someone put up no trespassing signs in our back yards,” says Cynthia Johnson of Flagstaff. She stumbled across the trade and then discovered a swath of the backyards in her neighborhood would become Ruskin’s because an old surveying error put part of their subdivision on national forest land he will receive.

Such surprises are not unusual. Legislated land trades normally are signed into law before anyone knows what’s happening. Homeowners discover neighboring national forest land is being transformed into a privately owned clearcut or subdivision long after it’s too late to stop it. Taxpayers don’t learn the total cost of such trades until after the fact — if ever.

Ruskin is not the only person seeking preferential treatment. Congress is giving its blessing to more and more land swaps as savvy brokers, wealthy individuals and Fortune 500 companies realize legislation is the perfect way to expedite their deals, and avoid environmental and public review — all of which can delay exchanges and make them more costly. Some even have figured out how to get the taxpayers to foot much of the bill.

Even when Congress doesn’t get involved, private brokers are regularly engineering complicated, behind-the-scenes trades for public land, taking taxpayers to the cleaners and huge profits to the bank, federal auditors and critics say.

The results: a $500,000 bowling alley in rural Nevada is swapped for public land in downtown Las Vegas that later fetches some $9 million. A $1.5 million cedar grove in northern Idaho earns sharp land dealers $8.75 million.

Three years ago, the General Accounting Office recommended the Bureau of Land Management and Forest Service abandon their land exchange programs, concluding they were irrevocably broken. The agencies instead should auction acreage they want to get rid of and buy what is worthy of public ownership.

Nothing happened. Instead, Congress appears to be mandating more land trades.

The result: Ruskin’s trade and other exchanges that simply are “taxpayer-subsidized real estate speculation,” says Aileen Roder of Taxpayers for Common Sense, a Washington, D.C. fiscal watchdog group.

Yavapai Ranch

A man named Ray Cowden assembled Yavapai Ranch out of five smaller ranches in the 1940s. It covers alternating square-mile sections of land the federal government originally gave to railroads to entice them West. The ranch is intermingled with Prescott National Forest land, creating a checkerboard of private-public ownership.

Ruskin’s late father, Lewis, joined forces with Cowden in 1960s. They always talked about trading with the Forest Service to eliminate the alternating ownership pattern — a common justification for land exchanges.

Ruskin grew up in Phoenix and spent summers on the ranch. He practiced pediatrics and anesthesiology before focusing on running the ranch and trading land.

A tall, lanky, likeable man in his late 50s, with a horse-shoe shaped belt buckle and a distaste for being called doctor, Ruskin drives a silver Suburban with a saddle in the back, dual cell phones up front and plenty of ranch mud on the outside. He keeps his cell phones humming, tracking the trade and making sure people in Washington, D.C. and across Arizona are pushing Congress to consummate the swap.

“We haven’t done a trade of this magnitude in Arizona in 50 years,” says Ruskin, who estimates he’s invested $1 million in the deal. “I’m the only guy in Arizona who could do this.”

He is critical of newspaper exposes about exchanges, saying the headlines always report when someone makes a killing, but overlook the fact that plenty of people also lose their shirts.

“It’s as risky as any other business.”

Extensive Homework

Ruskin consulted Forest Service officials and private companies across the Northwest and was told he would never succeed without Congressional assistance. That was reinforced when timber giant Weyerhaeuser Corp. ran into serious challenges with a 34,000-acre swap in Washington state called the Huckleberry Exchange.

Because such an administrative exchange — in which Ruskin would deal directly with the Forest Service — requires public hearings and environmental reviews, he risked long delays or a court challenge.

“If Weyerhaeuser couldn’t do an administrative exchange, there’s no way in hell the Ruskin family could,” he says.

“If they can’t pass the laugh test, they can’t get through the administrative process,” counters Janine Blaeloch of the Western Land Exchange Project, a Seattle-based nonprofit organization that advocates overhauling the land trading game.

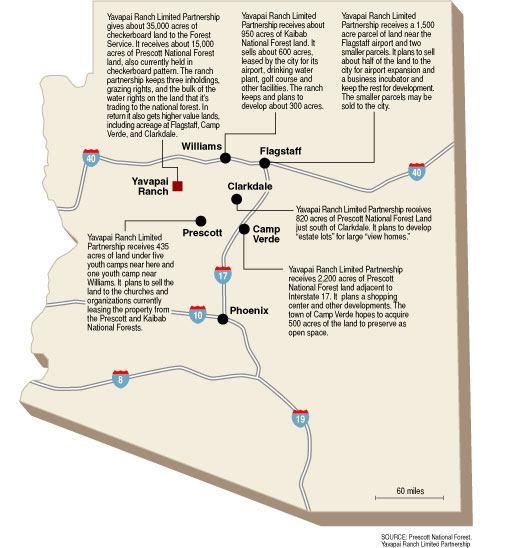

Here, Ruskin’s Yavapai Ranch Limited Partnership gives about 35,000 acres to the Forest Service. In return, he receives 15,000 acres of Forest Service land elsewhere on the ranch for a possible future subdivision. Ruskin also selected several parcels of valuable development land from three national forests, including 1,500 acres in Flagstaff. He will develop roughly half and sell the rest to the city for airport expansion and a business park.

In addition, Ruskin receives 2,200 acres near Camp Verde, 55 miles south of Flagstaff, surrounding an Interstate 17 interchange he figures is ready for a shopping center as well as 820 acres near Clarkdale ripe for “estate home” lots. The Forest Service added land it leases to the city of Williams and six youth camps to the list. Ruskin will sell each entity the land they are using — for the appraised price plus 15 percent, he says.

Illegal dumping is just one of the management headaches the Prescott National Forest cites to justify trading this parcel near Clarkdale, Ariz. to a private developer as part of the Northern Arizona National Forest Land Exchange. The land also is too close to rapidly growing towns to remain part of the Prescott Forest, Forest Service officials say. If traded, Ruskin plans to subdivide the land into estate-size home lots.

The Forest Service endorses the trade, saying it eliminates checkerboard ownership, improves wildlife habitat, protects nice forestland and eliminates the headache of leasing land to youth camps and municipalities. The agency admits it’s unusual to give up most of the water rights to land it is acquiring.

Still, “the net gain to the American public is tremendous,” says Steve Sams, public services staff officer for the Prescott National Forest.

The list of supporters includes the Grand Canyon Trust, the youth camps and the cities of Flagstaff and Williams. Camp Verde and Clarkdale’s town councils, which have flip-flopped on the issue, currently back it.

“I respect Fred Ruskin,” Clarkdale Mayor Michael Bluff says. “I’d much rather deal with him than one of the tribes” — a reference to other suitors for the nearby federal land.

Parched Prospects

Ruskin, the Forest Service and pro-trade advocates dismiss concerns over the resulting development exacerbating a desperate water shortage. More water has to be found no matter what happens, they say. The solution: Drill deeper wells.

That’s ridiculous, says Win Hjalmarson, a consultant and retired U.S. Geological Survey hydrologist who has studied the area for 40 years. “The water is all being used.”

Deeper wells will suck the last of the 1,000-year-old water out of the aquifer and dry up smaller domestic wells. Meanwhile, springs in the area are disappearing and wells are being abandoned because of high arsenic concentrations.

“At some point, there is a day of reckoning,” Hjalmarson said. “You are going to run out.”

Terri Brunsman’s family already has. A developer put in 530 homes nearby and “our well went dry,” says Brunsman, who lives in Clarkdale.

Her family drilled a new well. Neighbors hauled water. Now they face the prospect of Ruskin acquiring and developing Prescott Forest land next door to their home.

Uncertain Future

The Yavapai exchange passed the U.S. House of Representatives last November but died in the Senate. U.S. Sen. John McCain reintroduced legislation in April that is equally favorable to Ruskin, critics say.

Johnson and her neighbors believe they have successfully changed the legislation so they can buy the problematic portion of their backyards directly from the Forest Service rather than Ruskin. Still, it puts many of them in the awkward position of supporting a legislated land exchange they disdain. They also worry long-standing city plans for a park on the neighboring Forest Service land will be supplanted by a subdivision.

Other opponents say they would acquiesce if Ruskin drops his quest for Camp Verde and Clarkdale land. That’s a deal breaker, Ruskin insists. And the Forest Service defends his desire to acquire the most lucrative land.

“In order for Ruskin to realize an economic profit from this action, he has to have land he can make money off of,” says Sams, of the Prescott Forest. “The whole premise of doing a land exchange is you believe the value of the lands you are acquiring are going to escalate faster than the lands you trade.”

This means, “the benefits to Ruskin are so clear,” says Blaeloch of the Western Land Exchange Project. “And, like many land exchanges, the benefits to the public are questionable. Or none.”

©2003 Ken Olsen.

Ken Olsen, a reporter for the Vancouver Columbian, is examining the hidden world of public land swaps during his fellowship year.