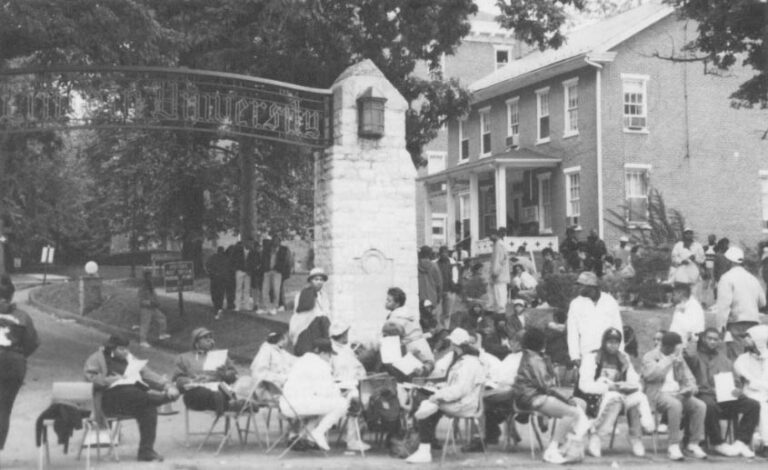

LINCOLN UNIVERSITY, PA.-Strolling across Lincoln University’s bucolic campus, set in southeastern Pennsylvania roughly equidistant from Baltimore, Philadelphia, and Wilmington, Delaware, tempts a visitor to populate walkways, classrooms, playing fields, and the chapel with some of its most famous alumni-Langston Hughes, the poet and playwright; Kwame Nkrumah, the first president of Ghana; Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall, among others-and dwell upon its storied past.

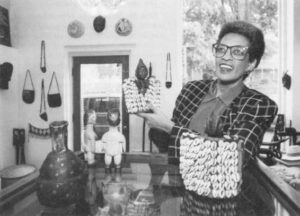

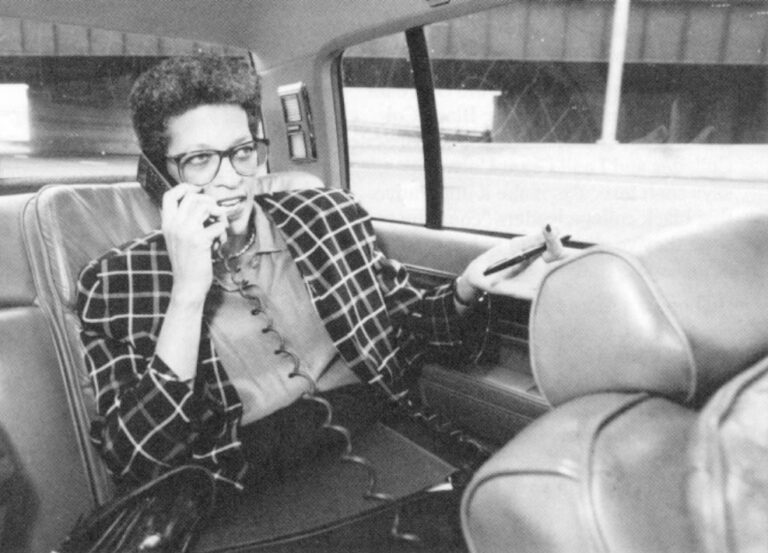

But Niara Sudarkasa, installed as Lincoln’s first woman president four years ago, spends her time planning the Lincoln of the 1990s. Her strategy is to use Lincoln’s historic importance to black America and the African Diaspora as the cornerstone of its future.

“By the year 2000 Lincoln has to be one of the best small colleges in the land,” she says, sitting in her light-filled office at Vail Hall, the college’s old library, now an administration building near the formal entrance to the campus. “Its academic programs have to be so outstanding they attract students and scholars from all over, and it’s got to become a crossroads for the discussion of global issues, especially as they affect the African Diaspora.

Sudarkasa’s vision is breathtaking when set against Lincoln’s relative physical isolation, its modest $20 million budget, its 1,300-member student body, and the growing financial pressures that all college and universities, but especially ones that are small and black, like Lincoln, now face.

Yet, on deeper examination, her determination to revitalize Lincoln, strongly supported by Lincoln’s trustees, faculty, and students, doesn’t appear at all Pollyannish.

In fact, Lincoln’s vision of its own future exemplifies the ferment roiling Hampton University, Howard University, Spelman College, Morehouse College, Bennett College, Xavier University, Florida A & M University and a host of other black colleges and universities.

Howard University’s new president, Franklyn T. Jenifer, in releasing a blue ribbon panel’s evaluation of that institution last year, described what is really their common goal. “What I hope it will result in,” Jenifer declared, speaking of his institution, “is not a new Howard, but a fitter Howard, a more focused Howard, a Howard that is prepared to take advantage of significant changes taking place before our eyes.”

Writ large, those ambitions also define the challenge facing William H. Gray, III, the former Pennsylvania Congressman who in September resigned left his post as Majority Whip of the House of Representatives, that body’s third-most powerful post, to become head of the United Negro College Fund.

The Fund has 41 members, all private black institutions. There are a total of 117 Black colleges and universities, all but thirteen of which were established under, states’ forced segregation laws.

Gray’s decision provoked much puzzled speculation. However, he has made clear he sees the move not as a stepping down, but as taking on a new challenge: Building up black institutions of higher learning at a time when blacks as a group are encountering significant obstacles to their pursuit of higher education.

“My job will be to raise the resources that will continue to widen the doorway of educational opportunity,” he told The Chronicle of Higher Education. “The more resources, the more people that can pass through the portals. It’s a very simple goal.”

That goal is a Grey family tradition. Although he himself attended the predominantly white Franklin & Marshall College, in Pennsylvania, his father was a president of both Florida A & M University and Florida Normal Institute (now Florida Memorial) and his mother was a clean at Southern University.

Grey’s decision was surely made easier by the fact that his scaling greater heights in the political sphere seemed blocked for the foreseeable future.

For one thing, Grey’s Democratic colleagues who occupy the two top House posts appear to have long tenures ahead of them. For another, Grey, the most nationally prominent Democrat in Pennsylvania, was not appointed by the state’s Democratic governor to the Senate seat of the late Republican Senator John Heinz-an appointment which would have been tantamount to nominating him to seek that seat on his own this fall.

Why not, then, take a post which would put him in touch with the highest echelons of both the black and white higher education communities, and the highest echelons of the corporate and foundation sector as well? With the U.N.C.F. in the midst of a $250-million fund drive boosted to high-profile status by the $50-million pledge of Walter Annenberg, the former publisher of TV Guide and former U.S. Ambassador to Great Britain-Grey has an extraordinary opportunity to carve out a new record of accomplishment.

However, Grey’s task, like that of Niara Sudarkasa at Lincoln, and other black college chieftains, will not be easy. The prestige of black colleges and universities as a group has never been higher, and enrollments are increasing. But, cautions Reginald Wilson, Senior Scholar at the American Council on Education, it’s easy to make too much of those rising enrollments and not understand the true nature of the pressures on black colleges, nor the crucial role black colleges and universities must now play in higher education.

Enrollments at black colleges have reversed their noticeable declines of the mid-1970s to early 1980s. In recent years their growth, in percentage terms , has surpassed those of their white counterparts. Officials at the National Association for Equal Opportunity in Higher Education (NAFEO), which represents all the black institutions, anticipate last year’s 248,697 enrollment figure will increase this academic year by up to five percent. But no one is predicting that the percentage of the total number of black college-going students who attend black institutions will increase from the 18percent level it’s held since the mid 1970s. Thus, Wilson asserts, while black institutions are a significant part of the solution, they aren’t THE solution to the problem of access to higher education for African Americans.

That point has been underscored this fall by the Supreme Court’s choosing to consider its first higher education desegregation case. The Court will decide whether Mississippi has met its legal obligations to desegregate its public colleges by ending race-specific requirements, as state officials argue, or whether it must do more-such as taking more specific steps to attract black students to predominantly white colleges and granting more monies to the state’s public black colleges to make up for past discrimination.

The outcome is likely to heavily influence the posture toward black colleges of legislators in the 18 other states which once deliberately fostered a segregated higher-education system. A finding in the state’s favor would likely put many public black institutions, of which Lincoln is one, and a number of private ones, in a very precarious position.

Fortunately, many chiefs of black colleges seem to have grasped the complexity of their situation and understand that they must maneuver with great delicacy.

Such thinking also stems in part from the likelihood that, as a report of the Pew Higher Education Research Program Sponsored by The Pew Charitable Trusts stated, the severe economic and political pressures already buffeting the nation’s colleges and universities will make the 1990s “prove a cruel end to the American century.” In other words: if legal rulings don’t first, financial pressures are likely to drive some colleges and universities under.

Joyce Payne, director of the Office for the Advancement of Public Black Colleges, of the National Association of State Colleges and Land Grant Universities, says such forecasts make it imperative that black college leaders “continue to be what they’ve always had to be-masters at managing their resources.”

There is a more comforting reason for the ferment, too: It is that two decades after the desegregation of white colleges and universities provoked numerous forecasts of their demise-and clearly led some institutions to lose their sense of purpose-black colleges and universities are now basking in a very favorable public light.

The source of their new appeal?

First, the demographic re-making of the country’s population, and these colleges’ own indisputable success in pushing students-many (but not all) of whom come to them with serious academic deficiencies-to academic achievement has proven they have ideas and methods their predominantly white counterparts need heed.

Secondly, black colleges and universities seem to be benefiting from the hunger for a black collegiate environment among some substantial number of black college-going youth.

Certainly, some of this growth stems from the racial incidents and controversies that have beset some predominantly white colleges and universities. But many in the black college and university community also cite what Christopher F. Edley, Sr., Grey’s predecessor at the U.N.C.F., slyly calls ‘the Cosby factor’ or ‘the Hillman factor.’

He was referring to the impact, on the one hand, of $20-million gift to Spelman College that Camille and Bill Cosby made in 1988, and, on the other, that of ‘A Different World,’ the Cosby-sponsored television sitcom set at ‘Hillman,’ a fictional black college (the opening credit shots show Spelman College).

However, despite the favorable publicity, the undertone that, because blacks attend predominantly white schools, these institutions have outlived their usefulness still exists.

“We make a contribution,” Sudarkasa says, directly taking that argument on. “We instill in black students what eludes them at many predominantly white institutions-the boldness to dare to compete at the cutting edge, and the confidence and the skills to succeed once they get there.”

Underscoring her assertion, Sudarkasa, who started college at Fisk, finished at Oberlin, and earned her doctorate in anthropology at Columbia University, brandished a sheaf of papers documenting that more than 70 percent of the nation’s black doctors, attorneys, teachers, engineers, pharmacists, and other professionals earned their undergraduate degrees at blacks colleges and universities:

These statistics don’t just stem from the pre-1965 days of segregated higher education in the South. According to the American Council of Education, 55 percent of the 6,320 African Americans who earned doctorates between 1975 and 1980 attended just 87 historically black colleges. The rest came from a total of 633 predominantly white colleges.

“Think of us in collective terms,” she says, “and you’ll realize we’ve been and continue to be the gateway to opportunity for black America. Singly, any one of us might appear to be replaceable. As a group, we’re irreplaceable.”

Women’s and Catholic colleges make the same assertion: the greater diversity of institutions of higher learning hasn’t eliminated the need for that set of particularistic institutions founded decades ago to provide educational opportunity then denied individuals on gender, race, or religious grounds.

Indeed, educators such as Leroy Keith, president of Atlanta’s Morehouse College, maintain that the continued existence of such schools should itself be considered a facet of higher education’s overall diversity.

But Keith also declares that, to be truly irreplaceable, black colleges and universities must overcome a dizzying array of challenges.

For instance, they must compete more aggressively with predominantly white schools for public and private dollars for research, scholarships, faculty salaries, and endowments, and for top black secondary school students-while continuing to welcome those students who are less well prepared but show promise. They must continue to diversify their student populations, and yet, keep as their focus the intellectual and economic development of African Americans. Their leaders must allow the faculty a greater say in the institution’s governance, and they must help improve the public schools in order to increase the number of black youths eligible for college.

Meeting such goals, for institutions which still suffer from nearly a century of federal and state governmental discrimination, would be a tall order even in the best of times. Now, given the decade’s economic forecast, it seems Herculean.

But one way to view the Cosby gift to Spelman is as a clear statement that those who support black colleges will have to make the tough choices to put those institutions in the best shape possible and to determine which colleges have the best chance of, not just surviving, but thriving.

Of course, the demise of a substantial number of black colleges has been predicted-wrongly-before. But this time the worrisome economic forecast for all of higher education seems to make it a greater possibility.

Yet, to listen to any number of black college perspective.

For example, the new international affairs program, which offers such languages as Chinese, Japanese, Russian, Arabic, and Swahili, seeks to prepare students for not only the foreign service, but private relief and development agencies, and entrepreneurial careers, too.

Also, the university’s year-old $10-million campaign is the centerpiece of an aggressive effort to push the endowment from $5 million to $15 million, increase research dollars by 100% a year from the current level of $2 million; increase annual private giving by 100% from current level of $675,000, and sharply increase the current 6-percent participation in giving of Lincoln’s own alumni by the mid 1990s.

That’s the reason Sudarkasa is on the road constantly. But she doesn’t appear to have neglected her plans to reinvigorate Lincoln’s communal spirit, either. The college calendar is dotted with notices of student led symposia and convocations featuring Lincoln’s own or visiting faculty and other prominent figures.

“I’m very proud of her,” said David T. Haines, a junior from Philadelphia and vice president of student government. “She brought us out of a serious deficit, and she’s been inspirational in telling us we have to stay focused on achieving as much as possible. We can see she thinks Lincoln is important. It makes you feel you’re part of something worthwhile.”

Haines, who two years ago helped organize a pan-black college student group to foster discussion of issues affecting black colleges, is himself a classic black-college story. The graduate of a middling Philadelphia high school whose scholastic aptitude board scores didn’t total 900, he had thought a college career was closed to him-until a relative suggested he contact Lincoln. Now, the government major is planning to attend law school.

Nonetheless, for all of the David Haines at Lincoln, and for all of Sudarkasa’s leadership skills, the question remains: Can Lincoln, and, by extension, the black college community, realize its goals?

The future, especially with the Mississippi Supreme Court case looming, is unknown. What is clear is that black colleges will face greater pressures to strip themselves of their racial identity: to enroll many more white students, even to cede primacy in their geographic area to predominantly white colleges and close their doors. Such a demand exemplifies how African Americans have been made to carry the burden of integration: Most black colleges have in fact always been integrated, while many of their white counterparts were founded specifically to perpetuate a segregated system of higher education. Yet, now that integration has arrived, it is the former, not the latter, who are often accused of having outlived their usefulness.

The one certainty is that, for black institutions of higher learning, the future is at least as full of difficulties as their past. But then, these colleges and universities have always faced a complex present and future. On the one hand, they do represent in bricks and mortar the attempt made over three centuries to shunt African Americans to a small corner of American life. And yet, they also represent the hope, faith, and determination of African Americans, and their white allies, to transcend that oppression and hew a place of comfort and opportunity Out of the American racial wilderness. So, if the past of black colleges and universities and their newly-recognized prominence today-offers any lessons, it is that the confidence they have in themselves has, in the final analysis, proven to be justified.

©1991 Lee Daniels

Lee Daniels, a reporter with The New York Times, has been researching black institutions of higher learning.