Most of the workers at the Videoton television factory in Székesfehérvár, Hungary were under no illusions about the reliability of the Ukrainian market, the destination for 5,000 television sets that had rolled past their assembly line. It was nice to have the work, and maybe this transaction would even go through (as so many others had not). But after all the deals and the lies and the false promises of the last three years, 5,000 television sets ordered by the Ukraine with its promise of substantive work, and even a small profit, seemed just a bit too good to be true.

And of course, it was.

The deal fell through. There was some misunderstanding concerning the price and the payment in hard currency. So the televisions returned to the plant and appeared on the assembly line to be rewired for the German market. Again they were rewired, again they were reassembled, again they were shipped. Again, the deal fell through.

SIDEBAR - Don’t Mourn, Privatize

All former communist countries share 45 years of a strong central institutional system which managed the economy as well as most other aspects of life. Today, what was once the regional imperative of “collectivization” has been replaced with the similarly urgent push for “privatization.” From large hopeless smokestack industries to medium-sized agricultural concerns to small store, front businesses, the key to prosperity, the binding force for the transition to a democratic pluralistic society, is seen to be economic reform. Removing assets previously held by the state and placing them into private hands may sound simple enough, but as Mihaly Laki, an economist with the Economic Institute and an advisor to the opposition party the Free Democrats, points out, “Me situation of privatization is terribly confused and there is no clear answer that demonstrates if the program is succeeding or failing. “The real story of privatization is that no one is sure. of what to do or what will come next.”

Each country copes with its own overlays of complications. The split of what was once the Czech and Slovak Republic has thrown its many faceted economy into uncertainty. Heavy emphasis on privatization is expected to shift as the programs and plans of Slovakia’s leader, the more left-leaning Vladimir Meciar, clash with those of the new Czech leader and former economic reform guru Vaclav Klaus. Though Poland may have been the leader in economic shock therapy, the unrelenting series of political crises have impeded progress. Romania, Bulgaria and Russia-not to mention the other former Soviet Republics- have made still less progress in the transformation of ownership.

Since 1989 a central paradox of freedom has emerged: while democracy can be declared in a day, a republic announced in a minute, free elections held over a weekend, the transition to a market economy, and the psychological transition to independence from the state takes very much longer.

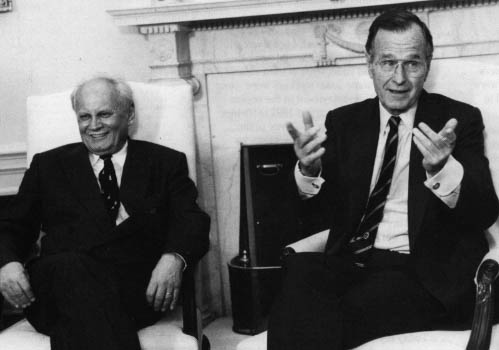

| Vaclav Klaus, Slovakia’s leader, won his position due to his plans for economic reform. Photo by AP Wide World Photos. |

Hungary’s transition differs from that of its COMECON neighbors because the former communist government bad set up the structure for a market economy. Hungary began limited economic reform efforts in 1968 with the New Economic Mechanism. Although stalled as a result of the crisis in Czechoslovakia, the NEM nonetheless established a curious economic hybrid that became known as “goulash communism” or “market socialism.” Its goal was to introduce market or quasi market mechanisms while continuing to retain the dominance of state ownership, The NEM created a second economy in which nearly everyone held a second private sector job. It was the predecessor for more radical economic reforms spearheaded by the last Communist government in 1988.

Throughout the Eighties, many Hungarians enjoyed the mixed benefits of being Eastern Europe’s most vital consumer society. New VCRs, home computers, western television sets and stereo systems, and small summer houses were the benefits of living in the late communist period. And yet, not only did the life expectancy for a Hungarian man drop by five years but, as President Arpad Goncz said immediately before taking office in 1990, “The major difficulty of the transition in Hungary is that. here people have a lot to lose.” Hungary was no Poland or Romania plagued by shortages of basic food items. Hungary was prosperous; Hungarians travelled. Hungary was the “most comfortable barracks on the Bloc.”

Today, Hungary has absorbed nearly half of the West’s investments in the East. In a region of massive political and social instability, 10.5 million Hungarians in Hungary enjoy relative calm. But 40% of the households live near poverty and in a recent survey the normally pessimistic Hungarians reached a new low in morale. Sixty percent said that Hungary is in a worse position now than before the elections of 1990. Industrial production has declined by 20% and personal consumption by 10% in less than two years. The homeless population in Budapest has reached 50,000. Most are men from the countryside who worked at a factories, lived in factory dormitories, were laid off and lost their home. Newspapers are full of stories about women unable to feed their children and pensioners only able to afford meat once a month; not surprising given that over the last five years the value of their pensions fell by 50%. Unemployment, which was a mere 2% at the beginning of 1991, is now at 10% and rising.

What happened? Put simply: bad timing.

No one could have predicted the difficulties of the transition, because no one could have predicted the totally transformed international political landscape. “In 1988 and 1989 when all of this began,” said economist Mihaly Laki, “we. were much more optimistic. We assumed that Poland and Hungary would have special status in the West and receive both financial and technical assistance. And no one dreamed that the Soviet Union would completely collapse. Now Hungary is only one of 20 or 30 post communist countries asking for help. But we are a small country and not so important to the West. Plus, there is an international recession and our greatest market collapsed with the Soviet Union.”

Marianne Szegedy-Maszak

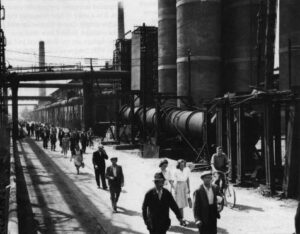

On this Monday afternoon, the peripatetic color T.V.’s rolled with stately grace on the assembly line, past the windows, past the dirty ashtrays, past the small bags of food the workers brought to eat during break, past the clusters of men and women slowly gathering to begin their shifts, and came to a halt. Within an hour, 40 television sets, like well-behaved children on a class trip, were lined up, waiting for their next round of rewiring. One worker wearily explained the situation with irony and bitterness.

“Now they say that these will go into the Hungarian market. But who will buy them? No one has money. If they have money they probably already have a television set. And if they want a new set they will buy a Sony or a Phillips, why waste their money on these old things?”

This worker’s frustration went beyond merely seeing the same television sets for the third time. Throughout the factory workers complained about markets, about competition, about management, but throughout the factory the subtext was a lamentation for times lost, for the unsettled existence they have endured, for the uncertainty created by a new management with few tender feelings for the workers or the company. These last 6,000 workers still remaining at the Videoton plant- manufacturing televisions and computers and radios and electronic parts-remember when the factory teemed with 20,000 Workers. They know that maintaining non-productive jobs for the sake of employing about 6,000 workers is no longer business as usual under the new capitalism.

Videoton embodies all the tensions inherent in privatizing large state-owned companies in former communist countries. It is a story of how economic exigencies simply cannot harmonize with social realities. Indeed how even economic factors are too ill-defined and subject to wide ranges of interpretation (not to mention political pressure) to serve as reliable guides for anything.

In the transition to a market economy, as in most other post-communist facts of Eastern Europe life, the practice and theory gap is profound. All the earnest economic models, the vectors, the flow charts, the groups of Western academics and consultants, the projections and anticipated rates of return have proven to be strangely oblivious to the unforgiving and chaotic realities of a society in profound transition. Western expertise, however necessary, lacks in understanding of institutions with no western counterparts. There are many large state-owned Videoton-type factories in Eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union. These monuments to communist “gigantomania” never existed in the western world. Oversized, under productive, they manufactured, in the, words of Hungarian economist Marton Tardos “too many things in quantities that were too small.”

The winners and the losers in the Videoton story illustrate the stresses and ambiguities of privatizing. What is clear, after spending any time looking at a place like Videoton, is that any quest for clarity in this context is hopeless.

WORKERS OF THE WORLD UNITE

For the 20,000 workers at Videoton, the early eighties were a time of prosperity and security. The Warsaw Pact needed their military electronics and Hungarian consumers wanted their stereos and television sets. As a result of the second economy, workers soon learned how to steal key items and establish their own private repair services after hours. It was said that workers could smuggle out the parts for a complete television set. Today, the front gate has an alarm system.

Sandor, a balding, bearded worker, explained “The management knew we repaired Videoton television sets at home so they weren’t too concerned with what we took out or brought in. On the other hand, they didn’t pay us very well at all here on the assembly line. I could have made 55,000 forints (about $733) a month repairing televisions if I had left Székesfehérvár.” Since Székesfehérvár is only 60 km from Budapest, there was a huge market there that could easily have been exploited. Compared with the average worker’s salary of about 11,000 forints, a month (about $150) the after hours income for those who worked in these factories was crucial.

Sandor remembers when Videoton was a flagship of Hungarian industry. Initially established in 1957 to make television sets, the factory grew in the Sixties to manufacture not only consumer electronics- stereo equipment, personal computers- but also supply the Warsaw Pact with military electronic equipment. Over time, 40% of Videoton’s product were connected to the military. Recently, during the Gulf War, Saddam Hussein proved the inadequacy of Videoton’s radio locators and communication system. More, a network of small shops than a fully integrated factory, Videoton was both completely heterogeneous and completely centralized in management. The various small factories never communicated with each other, only with central management. At one point, Videoton constituted 2% of the Hungarian economy. One measure of its importance was that its Director sat on the Central Committee of the Communist Party.

The overall company was not profitable, though certain segments of it were. III the mid-Eighties, the company received 3 billion Hungarian forint credit from the government to maintain operations. Conflicts between the various sectors of the factory and among managers grew. In 1987 a new director took over- well intentioned but lacking his predecessor’s talent to address the internecine conflicts within the company. Gradually the company slipped deeper into unproductiveness and debt.

REARRANGING THE TITANIC’S DECK CHAIRS

Laszlo Abraham was vice president for technical development and research before becoming the company’s new director in 1990. Today Abraham works for a German company that produces computer keyboards. III his late thirties, Abraham lives with his wife, and daughter in a comfortable house in Székesfehérvár which doubles as his office. When the phone rings, his wife dashes upstairs to turn on the tax machine.

Abraham explains work at Videoton like this: “The situation was much more serious than anyone realized.There was no guarantee of any assistance from the government and those of us in the middle management had to fight top management because they were the only ones with the political clout to do anything. But top management lacked the will to make the changes like lay off workers or rationalize production.”

According to Abraham, when he was director Videoton employed 18,000 but projected that 5,000 were unnecessary. He was prepared to lay off workers and reorganize the company, but politics intervened. A new national government-center right coalition headed by the Democratic Forum – had been elected. Before Abraham had a chance to reorganize, the new Minister of Industry replaced him with a Democratic Forum functionary – a former mid-manager at a bus company who knew nothing about electronics.

The Democratic Forum realized that no matter how necessary Abraham’s changes were, laying off 5,000 workers would not be possible.The next month, Hungary’s first free local elections would be held, to elect local mayors, city councilmen and other officials. A Democratic Forum member of Parliament announced that Videoton workers would be protected. Better instead to lay off one company manager and replace him with a party functionary.

After the local elections, in which the MDF government did manage to hold Székesfehérvár, it was decided that the solution to Videoton’s problems was privatization. This government had promised 50% privatization of its industries by 4994 and what better place to start than this huge white elephant? Call in the consultants. So what if the management insists on trying to keep the company together, insists on maintaining preposterous values for assets? And so what if 10,000 jobs have to be eliminated, a whole new team of consultants can help the workers!

THE HELPING HAND STRIKES AGAIN

The workers in a worker state who labored in factories like Videoton were not there for simply 40 hours a week. In a system reminiscent of the early Ford plants, the factory provided a social life. Workers met their future husbands and wives there, sent their children to the factory’s schools, were entertained at the factory cultural center and exercised at the factory gym. Vacations were in the factory’s camp on Lake Balaton. This was not simply a job, it was an organizing principal for a worker’s existence. When the rush to privatize took hold, this organizing principal was one of the first assets deemed negligible.

“Some workers are of course very angry,” says, Pal Schiffer, a documentary filmmaker working on a film about Videoton. “But most are deeply disappointed. They don’t feel as if anything that was important to them was respected. And they certainly feel lied to.” In a report by the head of the Central Council of Hungarian Trade Unions, Sandor Nagy wrote, “People who live on wages have been virtually the only losers in the past [two years] of social and economic change.” They have lost more than simple job security.

Amenities aside, Videoton management decided the soon to be unemployed workers needed some support. For the previous 40 years, unemployment was anathema in Hungary. As a result, workers have no mobility. Their lives and savings are poured into the small houses they owned. Even if they could sell them (which is unlikely) there is no place in the country to find work. Undeterred, management arranged for three Budapest specialists on unemployment to come to Székesfehérvár and devise a program which, as Janos Kollo an economist with the Economics Institute who was part of the team said, would “assist the company in a civilized way to deal with redundancy.

Of the 13,000 workers still remaining at the factory, 7,000 had to be fired. The team devised a four-point plan, a “cook book” Kollo calls it, for assisting the workers. The first ingredient was a “Party Committee,” comprised of equal numbers of directly elected representatives from the workers, and management. This committee would determine the rate and procedures for firings and mediate conflicts that may arise. The second ingredient was a newsletter to keep workers informed of negotiations, anticipated layoffs and resources.

As mundane as a newsletter may sound, to a Hungarian worker it was out of the ordinary. In the past, workers throughout Hungarian industry were the last to know what was bound to affect them.

The team also established an employment office at the factory to inform workers of other job or retraining opportunities. “At first we thought this would really be useful,” Kollo says. “Active marketing to assist the workers. But its primary function finally became paying unemployment checks and having a person sit at a computer, push lots of buttons and announce,‘The machine said no job.”’

The final objective was to allow workers to use existing Videoton resources vacant buildings, extra machinery- to establish their own small businesses. The theory was impressive, but given the decision-making paralysis of management, in practice it was impossible.’Me problem “was not with motivation or with conflicts within the factory.” Kollo said, “but with the very confused situation connected with privatization: a lack of authority.” No one was in a position to set a price on the assets to be privatized, much less set a real price, below the book value. No one was sure who had the authority to administer the small business center or offer workers necessary technical assistance.

In theory a recently unemployed worker was offered an array of options- a new job elsewhere, a chance to become an entrepreneur. The reality, however, was that redundancy notices were punched out as relentlessly as items on an assembly line. As Kollo admitted, “From the first time we went there, we had the impression that the firm was going to completely collapse anyway.”

Some workers were laid off, others took early retirement, still others went on allas idö or “waiting time” they would report to work once a week to determine whether they won](] work the next week and collect 90% of their salary. In the end, some,5,000 workers were dismissed. Unemployment in the region went from 2% in January of 1991 to 9% in December of that year. A survey of the laid-off workers revealed that 30 weeks after dismissal, 80% were still unemployed. Of all the workers contacted, 15% had left the labor market altogether and 47% were still looking for work by the end of the year. A Ford parts plant opened in 1992 in Székesfehérvár. For every one job there were more than 100 applicants.

Laszlo Kovacs, a worker who still has a job in the parts factory (if Videoton, explained the workers’ situation. “Next time I am going to vote communist. In the past when workers were paid they were paid sh- -, but at least it was reliable sh- -… Today my friends have lost their jobs, no one cares about the workers, and I don’t know if I will even get a pay check next week.”

Incredibly, during this time of turmoil the factory manufactured goods. Its products were in warehouses, not the market.

VISIBLE AND INVISIBLE HANDS

From the end of 1990 to July of 1991 the situation at the factory went from bad to worse. Management, resistant to any notion of radical change and reorganization, groped for a political solution. The managers stubbornly refused to split up the company.

A British management consulting firm was hired to determine the company’s assets and liabilities and devise a business plan. A routine job in the west, but in Székesfehérvár the British were forced to estimate that “the Videoton group has approximately 20-25 limited liability companies.”

A French company with the grandiose name of From the Atlantic to the Urals offered 14 billion forints (~186 million)a reasonable price for the entire factory. The small problem was that the French company had no money, its Parisian office was a post office box and legal questions had been raised about one of the major partners in Marseilles. It is testament to the Hungarians’ desperation, or their inability to perform due diligence for a transaction of this magnitude, that this sham continued for several months.

Various sectors like the printed circuits division or the television company or the computer division received some nibbles but all deals fell through. Management doggedly attempted to survive as a single unit.

Meanwhile, the year and a half of allas idö and bad deals, and attempting to hold together what had to fall apart, accumulated a debt of 27 billion forints from the State Bank. If Videoton was a dubious investment in 1990, it was untouchable in 1991. But that was exactly when it was touched. In August 1991, Videoton management asked the bankruptcy court to begin procedures. It became the first state-owned company to liquidate its assets. For the first time, the government said, we will give you no help, do what you can.

THE NEW MANAGEMENT

Parked in front of the Videoton cultural center is a shiny new black Mercedes 500 SEL with four antennas poking out and a starched white shirt hanging in the back. This is no visiting German millionaire; the car has Hungarian plates and is owned by Gabor Szeles, a successful Hungarian entrepreneur who is now part-owner and new manager of Videoton.

In August 1991, a new deal was crafted. The value of Videoton dropped to 4 billion forints (approximately $53 million), while its level of debt was 27 billion forints.‘Me investor refused to be encumbered with any of the liability, so in a peculiarly Hungarian deal, the state ate the debt. In a partnership with Szeles participating at 10%, the Credit Bank paying 75% and the State Property Agency holding 15%), Videoton was privatized.

Szeles is one of the beneficiaries of goulash communism. In 1981 with $400 U.S. dollars, he began a small basement enterprise to repair electronic measuring equipment. Two years later he began to work with personal computers. As restrictions on private enterprise loosened, he expanded. His company, Muszertechnika, moved into the IBM-compatible market in the late-Eighties, manufacturing low and high end computers for U.S. and Hungary. After crafting a lucrative deal with IBM, Muszertechnika employed more than 360 people, has several foreign offices and a team of aggressive employees.

Szeles, a powerfully built man, supported the Hungarian Democratic Forum, and even earned a seat oil its presidium. While Hungarian fears of foreign ownership have subsided, some speculate that keeping Videoton in Hungarian hands was a priority for the government, which made it more forgiving oil price and guarantees.

Upon taking over the company in January 1992, Szeles and his small team of young, Muszertechnika managers promised bright new days to the workers: 6,000 workers will keep their jobs, he said, he will corner the Russian military market again, he even has an order from a former Soviet republic for 50,000 television sets. When he meets with the American Secretary of Defense, he said, he will arrange for Videoton equipment to be purchased by the U.S. military.

Gradually those promises were forgotten. Or perhaps they were simply designed to lighten the morale of a demoralized work force.Today, Szeles is bursting with the vision of a series of industrial parks, a chain from Trieste to Milan in which Videoton would be a shining link. He even organized a conference for the Union A Industrial Parks.

Peter Lakatos is one of the new managers at Videoton. Slightly heavy, with scrubbed skin, lie presents a reassuring presence. At 30, he is a software engineer by training. His Videoton is a mess, a company with absolutely no internal pricing system, no reliable bookkeeping and a mistrustful and lazy work force. “In a good working company,” he says, “What Videoton did with 20,000 we can do with 3,000.” After the first four months of their management, the company was not operating at a loss. That does not mean that it made a profit, only that its downward spiral was arrested.

Lakatos begins to explain how Videoton fits in the broader market: Videoton doesn’t have a chance if the world recession continues; when interest rates are 38% and inflation is a stubborn 23%, no company could expand.

One of the other new directors is Otto Sinko, a 33 year-old electrical engineer who specializes in computers. Tough minded and watchful, he explains management/worker relations with a hint of irritation. “We have no social or emotional commitments here. We paid cash in anticipation that we will gain something in the short run and that there will be another kind of gain in the long term.”

LESSONS LEARNED

The new Hungarian government, in announcing its economic policy, referred to a “social market economy,” implying, somehow, a protection against the transitional hardships. But the gap that exists between commerce and society, between the imperatives of profit and the imperatives of individual lives, has never seemed so unbridgeable as today at Videoton and factories like it.

Janos Kollo, now writing papers on unemployment problems in post socialist Eastern Europe, reflects on what he learned during his year at Videoton. “Privatization in itself is not a solution to a crisis like this. It is almost, impossible to sell a company as one unit, no one will buy it. The process of privatizing will not solve the organizational problems necessary to be solved before privatization … It is also impossible to lay off thousands of workers in two weeks. Not just because it is very expensive, but the human costs at c terrible.”

Pal Toth has worked at Videoton for over 25 years. We stood in the printed circuits division of the factory, cavernous and relatively empty. The factory floor is full of machines in various stages of disrepair. A small, fine-boned man with thick glasses, the blue workers’ jacket covers a gray running suit, and the inevitable rancid cigarette is Clutched between his fingers. Toth met his wife at the factory, (she was laid off last year), his sons- were educated at the schools and one of them still works there. “We are still in trouble,” he says, as he rotates a metal plate covered with circuits slowly in his hands. “I won’t tell you how I voted the last time. But now I really don’t know if communism was better or capitalism will be better.” He looks up as, if struck by this thought for the first time. “I suppose I won’t be around long enough find out.”

©1993 Marianne Szegedy-Maszak

Marianne Szegedy-Maszak is a freelance writer concentrating on Hungary.