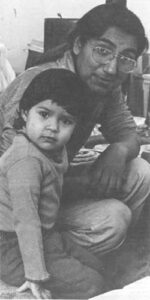

(SANTA FE) — Harold Littlebird sits in his wood-heated studio near Santa Fe, New Mexico, drawing a design on a clay saucer, his long black hair hanging down his back.

To many people, who have been taught to hold the melting pot image of America as sacred as the flag or the Statue of Liberty, Littlebird might be seen as a symbol. In their eyes, he has escaped the poverty of reservation life. He has married an Anglo; his pottery will be displayed soon at a convention center in Houston, Texas; and his daughter, Maya, at the time of the interview, was waiting anxiously for the Easter Bunny.

Assimilation. Joining the mainstream. Melting into the pot.

In fact, his pottery, while accepted by most Indians who are familiar with it, symbolizes such concepts to at least one Indian critic, who tried to make him leave an Indian fair because his pottery, with its modernistic butterflies and commercial clay, wasn’t Indian enough.

But Littlebird refused to go. “What do I look like, a Chinaman?” he asked. He’s fiercely proud of his work, which he sees as a continuation of traditional ways.

He works with commercial clay that he fires at high temperatures so it can be used for holding water or baking, reverting back to when Indians first developed pottery for daily use, not decoration.

His designs evolve from adaptations of old Mimbres (ancient Pueblo) designs.

His pottery, his poetry and his family reflect two worlds. But he disagrees vehemently when outsiders jump to the conclusion that the Indian culture is dying or that the reservations should be eliminated.

Since reservations were created in the 1800s, Western Indian tribes have faced tremendous social, and economic and governmental pressure to abandon their cultural identity. However, they’ve endured because of their family and tribal ties, their spiritual cohesiveness, their ability to adapt and the fact that so far, most tribes have retained some of their land.

Now, for more than 25 Western tribes that hold vast quantities of coal and uranium, that precarious balance is shifting. Whether the minerals’ weight will ultimately benefit the Indians or not remains to be seen.

The energy crisis and the announcement that the tribes own one-third of the strippable, low sulfur coal and one-half of the potential privately-owned uranium brought new attention to the Indians. Prior to 1975, when the public thought about Indians at all, it bought what legal scholar Felix Cohen called “the myth of the vanishing Indian.” According to this mythology, Indians are a people with a “colorful” past — useful for corn oil or anti-litter advertisements — and an impoverished present.

But a future? No, the pottery will soon have nothing but butterflies and the children have nothing but egg-carrying bunnies in which to believe. Indians will learn to adapt to the white man’s styles and values, become well enough educated to abandon their old ways and get well paying jobs in the city. The reservation system will be kept alive only until the last of the elders are gone. Like dust in the wind.

However, the figures dispute this concept. Far from vanishing, Indians are the fastest growing cultural group. The Bureau of Indian Affairs expects the 1980 census to show over 1 million Indians — more than when Columbus landed — and some put the figure as high as 3 million. While many more each year are getting college educations, they are returning to live on or near their home reservations in increasing numbers. While in 1970 about half of the nation’s Indian population lived on or near reservations, according to BIA figures, the percentage grew to 76 percent in 1977. BIA officials say this trend is continuing.

No one argues that the Indian ways have not changed. The interstate highways that pass through many reservations and the televisions have brought the Lutheran Hour, credit cards, prefabricated homes and modern health care. Children on many reservations understand their parents’ native language but don’t speak it. Young people have gone to Fort Bliss or Princeton and returned with slit skirts and ideas for reforming the tribal government.

Harold Littlebird’s situation is not typical — his father worked for the railroad in several states so Harold never lived on a reservation except when he was very small. He doesn’t know the language and feels like an outsider often amongst either his mother’s people at the Laguna Pueblo or his father’s at Santa Domingo.

However, many young people who go away to college face similar problems. Since respect for one’s elders is so integral to the Indian way, the conflict is more difficult.

“Pueblo life is a continuous type thing — you leave for awhile, and you lose that,” one man says.

“You come back with new ideas, and you’re looked at unfavorably by older people, especially if they think you’re doing it for yourself and not for the community,” says another.

The sense of community is very strong, and it is often enforced by secretiveness. Just one generation ago, no information was allowed out of some of the stricter communities, and many people still are critical of someone like Littlebird who goes around singing songs or reading poetry to other Indians and non-Indians.

“They’re willing to accept tremendous changes in their environment — a huge mine or several cars for each family. But yet they’re rigid about some things — down to the color of the socks you wear, it seems,” one woman says, referring to a particular community.

To some, such conflicts are frightening; they’re convinced the old ways will be lost because of the influence of the white culture.

Harry Early, governor of the Laguna Pueblo, predicts that in 15-20 years, through assimilation, the Indian way of life will be a thing of the past. “For today, we know we’re Indian people; we know where we belong; and we want to be left alone.”

Many of the younger people, however, see the conflicts as strengthening and believe the essential aspects of their culture remain, even if they are hidden sometimes.

Carlotta Concha, resource specialist for Laguna-Acoma schools, says, “Conflict shows that there’s growth. I don’t think we could call ourselves the Laguna Pueblo or the Santo Domingo Pueblo if our forefathers didn’t adapt.”

Carlotta Concha, resource specialist for Laguna-Acoma schools, says, “Conflict shows that there’s growth. I don’t think we could call ourselves the Laguna Pueblo or the Santo Domingo Pueblo if our forefathers didn’t adapt.”

She is glad that more Indian youngsters are now recognizing they have choices in jobs or ways to further their educations. “For generations, the students have been made to feel they should stay in their place.” Neither the Indian nor the non-Indian teachers have allowed the students to dream, she believes.

Simon J. Ortiz, who, in the ‘60s, was one of the first three young people to leave the Acoma Pueblo for college, points out that the Indian people have never been static. Without change, he thinks the exploiters would have gotten their wish for a vanishing people.

A poet and a literature professor at the University of New Mexico, Ortiz says his aunts and uncles caution him not to forget his first responsibility is to his people. “If I keep that in mind, and I do, I could never really be seen as an oddball. I may be working with a new method (written as opposed to oral literature), but it’s not odd,” he says.

Littlebird believes that a spiritual bond helps Indian people transcend their differences. “Periodically there are times when people tend to forget what’s important, but there are always certain older people who know these things. They bring them back.”

While living away from the reservation, he tries to instill certain values in his children — to see the sacredness of things and to listen to older people. He takes them home often to visit with their grandmother at Paguate on the Laguna reservation.

Home. While some tribes live on reservations that were not part of their original territory and share them with traditional enemies, the reservations are now home.

“I don’t think Indians would be a people without reservations,” says Winona Manning, a historian for the Western Shoshone Tribe. Manning, who lived off the reservation while getting her education, says, when pressed, “Well, maybe you can retain your culture, but your children can’t. When I went home for a visit, my kids acted like city kids.” She has since moved back to the Duck Valley Reservation in Nevada, but she knows several Indians who stayed in cities. “They still know where their homes are,” she says.

“This is where we belong,” says Harry Early. “We’re very closely knit; we identify with the Laguna Pueblo; we identify with the land.”

Due to its ignorance of such ties, to lack of foresight and to more selfish reasons, Congress periodically has tried to rescue Indians from the reservation system and from their ward-like relationship with the U.S. government.

Starting back in 1887 with the General Allotment Act, Congress allotted 80 or 160 acre parcels of reservation land to each tribal member and opened the “surplus” for settlement or development by non-Indians. This policy wasn’t officially reversed until 1934, but by then Indians had lost almost two-thirds of their land.

In 1953, Congress tried termination. It passed a resolution that called for granting Indians “all the rights and prerogatives pertaining to American citizenship” and freeing them from federal supervision and control.

The Menominee Tribe of Wisconsin was chosen for termination in 1954 because it was considered particularly prosperous and socially advanced, according to Gilbert L. Hall in his book, The Federal Indian Trust Relationship published by the Institute for the Development of Indian Law. The reservation became a county, and all of the tribe’s assets were turned over to a new corporation, Menominee Enterprises, Inc.

The effects were nearly disastrous. When profit-making instead of providing employment became the objective for the tribal sawmill, jobs were reduced by 25 percent; the percentage of Menominees who received public assistance rose from 14 percent in 1954 to about 50 percent by 1973; and thousands of acres were sold to non-Indians to meet tax obligations, according to Hall. Finally in 1973 Congress reinstated the Menominees and in 1975 passed the Indian Self-Determination Act, which reaffirmed the U.S. government’s responsibility as trustee to protect tribal lands and resources. However, between 1934 and 1974, Indians lost another million acres from trust status because of termination bills or condemnation for federal dams and highways, according to Hall.

For now it looks as if Congress isn’t going to attempt another wholesale ci sion of reservation lands, if for no other than economic reasons. In 1978, Congress turned its back on Rep. Jack Cunningham of Washington state, who introduced a bill to abrogate all treaties and set up corporations, much like the ill-fated Menominee Enterprises, Inc.

Interior Secretary Cecil Andrus argues that treaties, however, are legal contracts that are “every bit as legitimate” as, for example, home mortgages. The Indians let go of their property in exchange for the U.S. government’s guarantees that it would protect the land, water and other resources, Andrus says. Just because energy was found upon the land doesn’t relieve the United States of its legal obligations, he says.

One of the options under Cunningham’s “Native American Equal Opportunities Act” would have been for the United States to buy treaty rights. But the Library of Congress estimates the value of the Indian fishing rights in the Northwest alone at $200 million.

While direct efforts to abrogate treaties are not seen as an imminent threat to reservations now, Indian leaders anticipate other battles, which, for many tribes, will be on the energy front.

According to the Council of Energy Resource Tribes, the unemployment rate on reservations is eight times the national average, and their income level is about one-fourth the national average.

Energy development could mean jobs for Indian miners, attorneys, geologists, land use planners and economists. It could also bring millions of dollars into the coffers of tribes that have not yet embarked upon development.

But the energy riches could also buy destruction. The tribes that have already leased their minerals can tell them something about that.

Twenty-seven years ago, the Laguna Pueblo, through the BIA, leased uranium to Anaconda Copper Co. When the mine opened, many Lagunas were able to return to the reservation for jobs, and now the tribal council depends upon royalties for the majority of its budget. Some of the money has also been distributed in annual checks to Lagunas on the reservation.

Suddenly the people had an opportunity to provide for their families while staying at home. As one miner explains, “Buying food for my family gradually became more important and preserving the land, while I still believed in it, became less important.” Families who once lived in adobe homes with wood stoves now live in new frame housing and face $150 to $200 propane bills a month. With cars and credit cards, their financial needs have grown.

Although the Lagunas have historically put a high emphasis on education, miners need only be 18 years old. Many students have dropped out of school to work there.

Now the pit spans nearly 1,000 acres and is the biggest open pit uranium mine in the country. But the ore is almost gone. While Early and the tribal council are negotiating with several companies for other leases, the price of uranium is falling; the best ore has been mined; and the prospects for new mines look bleak. More than 200 people will be unemployed, and many will have to move if they want to continue working.

To add to their trouble, Anaconda is having trouble finding a way to stabilize the site to keep hundreds of acres of radioactive wastes from washing or blowing away.

Simon Ortiz thinks this is a prime example of why mining can’t be the panacea for holding onto the land and the people. “Especially from the standpoint of economic self-sufficiency, they’ve become worse off,” he says. He believes that without fundamental economic and political change in this country, Indians are not going to benefit from energy development; mining just continues the process of colonization.

Other Indian leaders say energy development can benefit tribes — if they hold the reins themselves and if the development is limited in size. Representatives of several tribes that are contemplating energy development attended a Federal Bar Association convention on Indian law in Phoenix in April. There, tribes that have already leased some of their coal and uranium cautioned them about many critical questions that have not been resolved yet:

Who can tax the mineral production — the state, the tribe or both? Who sets the environmental regulations and who enforces them? How is energy development outside the reservation boundaries controlled? Where do tribes go for technical and legal advice? How do tribal scientists and planners get training? Who gets the water? And can the tribes say no to the nation’s demands for their energy resources?

These questions will only be resolved after years in the courtrooms, the halls of Congress and tribal council meeting places. The tribes will need to assert their sovereign rights and at the same time be willing to bargain reasonably on less important points. They will also have to call upon the old values that have helped them endure before.

Ultimately, the future of the Indian people is not just an Indian question, according to Simon Ortiz. “Instead of asking what are the Indians going to do, you should be asking about our responsibility as a nation. What is the future of this country? “

If greed and a missionary zeal for its own culture prevail, the United States and its people won’t really have won.

©1980 Marjane Ambler

Marjane Ambler is investigating “Indian Energy Policies and Their Effect on Tribal Self-Sufficiency.”