Lorem ipsum dolor sit (NEW TOWN, N.D.) — When oil prices skyrocketed recently and exploration crews began arriving on the Fort Berthold Reservation in North Dakota, the activity was a mixed blessing to the Three Affiliated Tribes (Arikara, Hidatsa and Mandan). With 40 percent unemployment and few sources of income other than tribal or federal jobs, many tribal members looked forward to the increase in jobs and royalties. However, the companies left dynamite lying around, cut fences and disrupted the lives of the people.

“They were running rampant over the reservation,” according to the local Bureau of Indian Affairs superintendent, Harrison Fields (Pawnee), whose job it is to protect the land from such things. When the BIA didn’t respond to their complaints, some landowners resorted to guns to protect their land and livestock.

The tribes, frustrated by the BIA’s lack of control, adopted their own seismic exploration regulations, issued permits and hired Indian guides (paid by the company) who accompanied each exploration crew to make sure that the companies followed the regulations.

While public attention has focused on money — particularly on comparisons between the Council of Energy Resource Tribes and OPEC (the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries) — the critical issue to the tribes and CERT is control.

The issue is also crucial to the country as a whole. Without control, the tribes don’t plan to open their lands to further development. At stake is the biggest untapped energy bank in the country: one-third of the nation’s Western low sulfur strippable coal; one-half of its potential privately-owned uranium; as well as huge reserves of oil, gas, oil shale and other forms of fuel.

While most tribes with oil and gas resources have been producing for years, only three tribes with uranium and three with coal are now producing. The Navajo Tribe, the biggest private energy owner in the nation, has signed only one mineral contract in the past decade. Other major coal-owning tribes — the Crow, Northern Cheyenne and Three Affiliated Tribes — narrowly escaped inequitable coal contracts approved by the BIA in the early 1970s and imposed informal moratoriums on coal development. The moratoriums have been lifted only by the Crow when they signed a coal contract with Shell Oil Company this summer.

But 1980 begins a new era in Indian energy development policies. As Ken Fredericks (Mandan-Hidatsa), director of real estate for the BIA in Washington, D.C., said, “The tribes’ degree of sophistication in business and their ability to cope with the blue-eyed world has increased tremendously in the last five years.”

This sophistication is now being recognized by the energy companies, the Congress, and, grudgingly, by the BIA. At the same time that the tribes’ abilities have been growing, Congress and the courts have been acknowledging their jurisdiction in energy development matters. One of the first decisions facing the next Congress will be a landmark bill composed jointly by CERT, the coal-owning tribes and the federal Office of Surface Mining. Mandated by Congress in 1977, it provides tribes with the opportunity to assume full regulatory authority over coal on their land.

Of course with billions of dollars, millions of acres and thousands of regulators’ jobs at stake, this new era won’t be without its problems. The 1980 battleground has already been filled with skirmishes between the BIA and CERT, the BIA and the tribes, and different factions within tribes.

One Reservation’s Story

At Fort Berthold, the gradual shift of control from the BIA to the Three Affiliated Tribes has created a wariness that sometimes mars their superficial cooperation.

BIA Superintendent Fields signs both the BIA and the tribal permits for each company’s exploration when they are submitted to him, even though the tribal regulations and permit system have never been officially approved by the BIA and, in fact, he doesn’t expect some parts to be approved by Washington. His office provides a truck, gasoline and a salary for a field inspector whose work orders come from the tribal Office of Natural Resources and Energy Development (ONRED).

Ultimately Fields believes regulation of energy development is the bureau’s responsiblity, and he is seeking funds to hire staff to try to keep up. “But we don’t have the staff or the resources to handle it right now so it’s been a relief for us to have the tribes assisting the bureau,” he said.

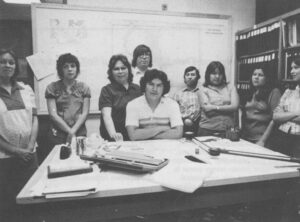

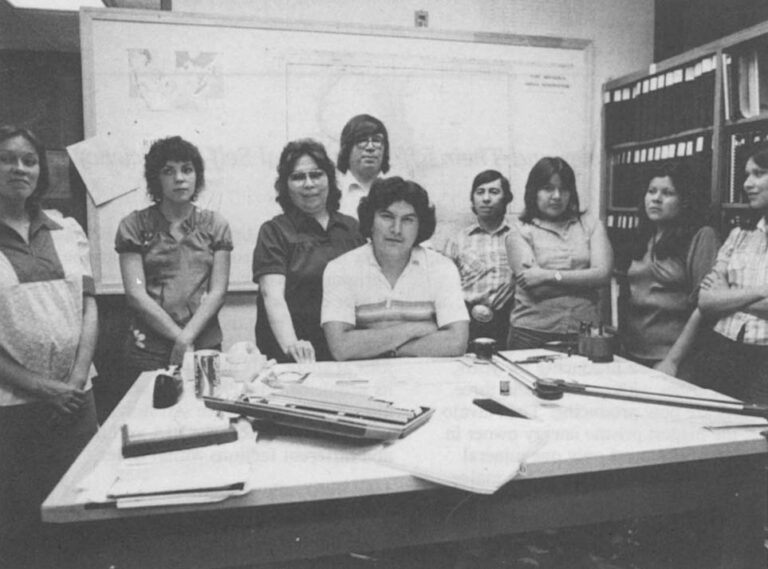

The director of ONRED, Hugh Baker (Mandan-Hidatsa), visibly bristles when he hears Fields’ patronizing remark about assisting the bureau. He is proud of his young, dedicated staff, all of whom are from the area. He is also proud of the tribal exploration regulations, which are tougher than the bureau’s and which were developed by his staff after studying other agencies’ requirements and adapting them to the local situation. He resents the BIA’s attempt to staff up its own office when his office is handling much of the work.

Baker points out that under the Indian Self-Determination Act of 1975 (Public Law 638), Congress intended to encourage tribes to contract with federal agencies to provide federal services. The act also says tribes can borrow federal employees, receive grants to carry out the services, and direct the BIA to adhere to tribal priorities.

However, the BIA has often resisted tribal self-determination efforts. “They say they don’t trust us, which is true, but they’re also protecting their own jobs,” Baker says. He is convinced that when the tribes get the mechanics in place, the ONRED staff will be capable of taking over regulation of both exploration and development of energy of the reservation.

Fields supports the ONRED program — to a certain degree: “But no tribe can take over any facet of trust responsibility.”

The definition of trust responsiblity is now the subject of a raging nationwide battle. It is becoming obvious that even top level Interior Department officials don’t agree on what the term means: Can tribes market their own resources? Who has authority over individual Indians’ (allottees’) lands? Can tribes write their own regulations if they are tougher than the federal regulations? Who enforces them? Can tribes enter into contracts other than the traditional leases?

The BIA’s Ken Fredericks is now rocking Washington offices by saying he doesn’t think the Interior Department’s new Indian mineral leasing reforms, published in August, are legal — even though the department has been working on them for over three years.

The regulations provide for alternatives to the traditional lease contracts, such as tribal profit sharing, partnerships and joint ventures — options that can mean millions of dollars difference to a tribe as well as allowing the tribe to participate in decision making after the contract is signed. In some areas the BIA has already approved such contracts without the regulations while in others it has refused. Now Fredericks is saying the BIA doesn’t have the statutory authority to approve them.

“We’ve been trying to make these statutes, which were written at a time when the BIA was a very active trustee, bend around 180 degrees, and it’s just not working that well,” Fredericks says.

Fredericks is concerned that when the bureau bends the statutes to fit the demands of a tribe, the tribal council will change and the new council will bring its lawyers in to accuse the BIA of violating the law.

He admits the problem should have been recognized five years ago. “But five years ago there wasn’t pressure from so many tribes seeking to enter joint ventures with energy companies.”

Fredericks believes tribes should be able to enter into contracts other than the traditional leases. But he balks at giving them full permitting and regulatory authority. “We can’t administer under our trustee role if we give tribes all that responsiblity.”

Barb Lindley, senior planner at ONRED, admits she is not a bureau fan. She points out that their overhead costs are extraordinary — the American Indian Policy Review Commission estimated that 78 to 90 percent of each dollar allocated for Indians is used to administer the BIA. “But every time we ask for something, they say they’re short-staffed,” Lindley said. However, she doesn’t want to abolish the bureau as some naive critics have suggested. The bureau is the only thing standing between the tribes and termination of treaty rights. She says the tribes have to create the internal structure necessary for taking over more of the bureau’s responsiblities. They also need to establish a financial base.

Unlike state or city governments, Indian tribes cannot collect property taxes, issue tax-free bonds or collect income taxes. Consequently, they are almost entirely dependent upon federal grants and programs for money to run their governments, educate their people, and provide housing, sewer, and water facilities.

For example, Lindley’s job and several others’, including Hugh’s, were endangered recently due to an apparent misunderstanding between ONRED and the BIA.

Baker said that two high-level Interior Department officials assured him that the ONRED would be funded again for fiscal year 1980. However, six months after its 150 thousand dollar proposal had been submitted to the local BIA agency, Baker discovered that it had not reached the area office. The proposal was submitted again, but by then, the funds had been obligated.

BIA officials at the agency and the area office contend the tribes were never told the office would be funded for fiscal year 1980. Fredericks in Washington says the money was allocated for CERT instead.

ONRED eventually suceeded in getting the money through another federal agency, the Administration for Native Americans. Whether or not one assumes the funding problem was deliberate, the temporary crisis illustrates the hazards of being dependent upon federal grants. Baker and other Indian political experts consider fragmented planning development to be the next biggest hurdle to coherent tribal control over energy development, second only to the BIA.

Planners are forced to spend their time writing grants that respond to Washington’s priorities rather than to their own tribes’. Ken Deane (Arikara), a tribal planner at Fort Berthold, says the tribal administration is a maze of different offices, foster children named after the federal agencies that fund them: Housing and Urban Development, Community Action Program, Economic Development Administration, Environmental Protection Agency, Administration for Native Americans. The tribal council is responsible for 25 federal programs funded by 10 different federal agencies, each with its own budgeting and reporting requirements. None can plan beyond its year’s funding, and no one can effectively coordinate them.

When the Corps of Engineers chose the Fort Berthold Reservation for the site of a giant reservoir in 1945, for example, the BIA funded housing in new communities since 90 percent of the people had to be relocated. Years later HUD came in and funded more housing, which was hooked onto the existing sewer and water systems. Later the Indian Health Service realized the sewer and water facilities were incapable of serving the increased population so an IHS grant was necessary.

While the Three Tribes have been interested in comprehensive planning and management for years, Baker says, they had trouble until recently getting federal granting agencies to respond. If the BIA had fish and wildlife funds, they couldn’t be used for a natural resources department that included fish and wildlife and other functions.

David Lester (Creek) shares the Indians’ concern about fragmented planning. When he became director of the Administration for Native Americans, he designed a grant program that provides for long-term funding. Equally important, tribes must show that they are working toward the goal of self-sufficiency — programs that will either be phased out or bring in the funds necessary to continue operation through taxes or fees.

The Three Tribes’ proposal was one of the first accepted under the new program, and now CERT uses Fort Berthold as an example of planning by objective. The 25 different programs are being placed under three departments; each department head will develop objectives; and the tribal council will determine which objectives should be priorities.

ONRED is becoming more self-sufficient: several of its staff members are already paid by fees from the energy companies, and the office hopes to be 33 percent self-supporting by December of next year.

However, full tribal government self-sufficiency will be difficult if not impossible, largely because of the legacy left from earlier eras when the federal government considered reservations temporary asylums. More than 150,000 acres, including the fertile river bottomland, is covered by the waters of Lake Sakakawea, which primarily benefits non-Indian farmers and industry. Most of the reservation’s good farmland (45 percent of the reservation) is owned by non-Indians who homesteaded there when the federal government opened the reservation in the early 1900s.

The tribe owns only five percent of the oil mineral rights, so if more oil is found on the reservation, royalties will go primarily to individual Indian landowners (allottees) or non-Indians. While the tribe owns 52 percent of the coal that underlies the reservation, according to Baker, tribal leaders are hesitant to develop it because of the relatively severe environmental and social impacts. Nor will they get any income or have any control over plans for a coal gasification plant that is to be built just outside the reservation boundaries.

Energy-rich tribes across the country are facing similar dilemmas. Through CERT and other organizations, they are sharing information and keeping track as different tribes take the vanguard in new areas.

The U.S. Supreme Court is expected to consider a corporate challenge to the Jicarilla Apache Tribe’s severance tax on oil. The Jicarilla also recently became the first tribe to take over most of the oil wells on its reservation in northern New Mexico. Many tribes are considering seeking clean air designations, authorized under the Clean Air Act, which helped the Northern Cheyenne Tribe force a nearby coal-fired power plant in Montana to use the latest clean air technology. The Salish-Kootenai Tribes in Montana have a personnel code, similar to Civil Service, which CERT uses as a model for other tribes. The Navajo Tribe has enacted several taxes, all of which are being challenged in court, to increase their monetary return from reservation energy development.

Baker hopes the current movement toward Indian control over energy development continues, no matter which administration is in power. “It would be asinine for anyone to disagree with the trend in Indian energy development. Either there will be no development or orderly development, meaning a tribal government structure that assures regulation and monitoring, employment preference and proper return… You just don’t walk over tribal governments anymore.”

©1980 Marjane Ambler

Marjane Ambler is investigating “Indian Energy Policies and Their Effect on Tribal Self- Sufficiency.”