The Sept. 11, 2001 terrorist attacks on America has focused world attention on Peshawar, from where U.S. military strikes could still come.

Peshawar — only thirteen miles southeast of the Khyber Pass, with Afghanistan beyond — is a rugged, lawless place, riven by religious fervor and violence and rich in political intrigue. The capital of Pakistan’s North-West Frontier province is a sprawling town of pastel colored villas and Afghan refugee camps, militant training centers and madrassahs, the religious schools where jihad, more often than not, is preached. It is a center for arms, drugs and a booming black-market economy.

The key staging area for the jihad in Afghanistan, Peshawar is an example of an economy which is nearly bankrupt and has a $36 billion foreign debt, a black market economy which exceeds 55 percent of GDP, and a gun-loving culture. In the North-West Frontier province and surrounding tribal agencies, there are thought to be roughly seven million Kalashnikovs — one for every grown man.

This is Pakistan’s recently self-appointed President, General Pervez Musharraf’s inheritance.

When he came to power, in a military coup in October 1999, Musharraf pledged to reverse all this: to crack down on endemic corruption; to jumpstart the economy; to “deweaponize” the country, and to rein in its growing band of Islamic militants, who are schooled in the madrassahs, trained in Afghanistan, and go on to fight in the disputed state of Kashmir –which is claimed by both India and Pakistan and has been divided between them for half-a-century.

It is a vicious cycle, and one which the General has been unable, or unwilling, to reverse. His supporters insist that if Musharraf has not fulfilled his promises, it is too soon to conclude that he has broken them.

Yet, over the past year, he has acquiesced consistently to the demands of the religious right, retreating from his pledges to document the madrassahs and bring them under state control; to liberalize the country’s draconian blasphemy law; and to consider (under the strong urging of the United States) the feasibility of signing the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty. It has become increasingly difficult to differentiate between Musharraf”s surrenders and his tactical retreats which, in turn, makes it difficult to say which direction Pakistan will take.

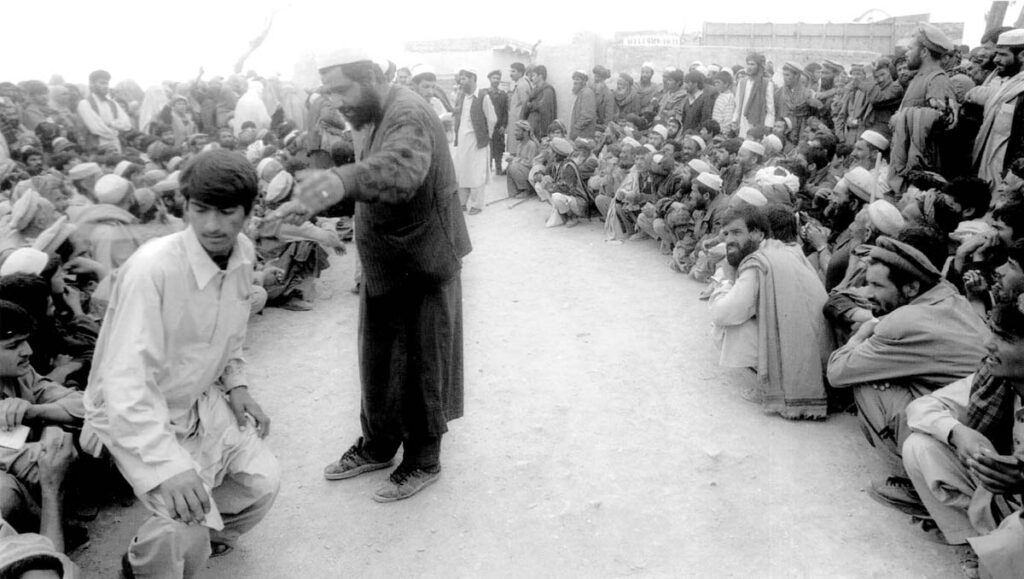

I had come to Peshawar to meet the Maulana Sami ul-Haq, one of the most powerful, and one of the most anti-American, of Pakistan’s religious militants. He is the chancellor of the al-Haqqania madrassah, which his father had founded, and which is the largest in the Frontier and, like its leader, one of the most militant in Pakistan.

As we sped along the highway, we passed brightly-painted lorries, which are unique to the Frontier, and whose cargoes more often than not contain smuggled electronic goods, a lucrative business controlled in large part by the Afghan mafia. We weaved our way in and out of a procession of cars, festooned with religious banners and flags, whose occupants were enroute to a fundamentalist rally outside Islamabad, which would attract hundreds of thousands of people, both Pakistanis and Afghans.

(Political parties and political activities are banned in Musharraf’s Pakistan, but the religious right continues to organize, rally and recruit, having convinced the government, or so it appears, that their organizations are more Islamic, than they are political –all of which has led the Human Rights Commission of Pakistan to accuse the General of being a “silent spectator” in the rise of the orthodox clergy and fundamentalist Islam.)

I glanced out the window and watched clusters of Afghan refugees tending their tiny shops. Afghanistan has been at war for twenty years, and the refugees continue to spill across the frontier, now fleeing the ruling Taliban, whose Islamic strictures are extreme and often bizarre. Women largely are not permitted to work. Girls may not attend school. Television, cinema, and music are banned. So is kite flying. Women are not permitted to wear white socks. Both of the latter are considered to be sexually provocative.

Afghan refugees now dominate Pakistan’s northern towns and, as we continued toward the madrassah, it became apparent that, for all practical purposes, Afghanistan had effectively moved fifty miles south.

A friend had come with me to act as my interpreter, and as soon as we entered al-Haqqania’s gates, we discovered how vast it is. Spread over fourteen acres, on the Grand Trunk Road, an hour or so east of Peshawar, it has scores of classrooms, administrative buildings, mosques and dorms, and a state-of-the-art computer room. Much of its funding comes from the wealthy kingdoms and sheikdoms of the Persian Gulf, particularly Saudi Arabia.

No armed men were visible early that afternoon but, a few weeks after our visit, scores of gunmen in camouflage fatigues, their faces covered by black ski-masks, would stand guard across the campus as some three hundred of Pakistan’s leading Muslim clerics met to pledge their support to Osama bin Laden, the accused Saudi terrorist who is the chief suspect in the September 11thterrorist attacks.

We were ushered to a verandah abutting the Maulana’s drawing room. There, ten or so young men lounged about, including the Maulana’s second son, Rashid, who was in the process of being married, in a ceremony that lasts three days. His father was supervising the final arrangements for the festivities, so Rashid and his friends had been asked to entertain us until the Maulana arrived. They proceeded to brief us on Peshawar’s events of the day. The previous evening, a dozen or so armed militants had met with great success in smashing an equal number of satellite dishes and TV sets. The papers that morning had reported that the United States was about to bomb Afghanistan again (as we had done, in August, 1998, after we accused Osama bin Laden of bombing two of our African embassies.)

“What will happen here if that occurs?” I asked.

“Holy war,” one of the young men politely said.

The Maulana Sami ul-Haq rushed onto the verandah, followed by servants ferrying trays of tea and coffee, fruits and sweets. A weathered man of sixty-five with a heavily lined face, small brown eyes, and a straggly beard, dyed orange with henna (which is quite fashionable here), the Maulana is also a politician and a former Senator. He is the leader of one of Pakistan’s more radical Islamist parties, which seeks the immediate imposition of the more punitive aspects of Shariah, or Islamic law. He told me immediately that al-Haqqania had 2,500 students; had issued nearly a million fatwas, or religious opinions, over the years (not mentioning the fact that a number of them had endorsed the fatwas issued by bin Laden in Afghanistan); and that 95 per cent of the leadership of the Taliban had studied here.

Pakistan’s commitment to that leadership has been reinforced since General Musharraf seized control. As a result, not only has his powerful military intelligence organization, Inter-Services Intelligence, or ISI, intensified its efforts to impose its own solution on Afghanistan, by accelerating its military training of the Taliban and by recruiting volunteer soldiers (from madrassahs such as this) but, since last spring, it has planned pivotal military operations for Afghanistan’s fundamentalist regime, as the two sides attempt to wrest control of ten per cent of the country in the north, which remains in the hands of the remnants of an opposition force – a force supported by India, Russia, and Iran. So, I asked the Maulana to tell me about the Taliban’s mysterious ruler, Mullah Mohammed Omar. For despite the fact that Pakistan has gambled heavily on him, except for a handful of officers from the ISI, few in successive governments of Pakistan, including General Musharraf, have ever met the man.

“He’s a very good friend of mine,” Sami ul-Haq began. “He considers me as a teacher, and your country should give him a medal for saving Afghanistan! Mullah Omar and the Taliban didn’t just fall out of the sky. They’re the children of the mujahideen, the children of the jihad, which your CIA trained. Mullah Omar was an ordinary soldier who fought in that war and he lost an eye in it. He was an unnamed, unknown Talib who came from nowhere. We think that God must be behind him. When I last visited him in Kandahar, I found him in a garage outside his house. He was sitting on the floor, with a wireless, ruling Afghanistan. He has no need for pomp and ceremony, for television or air conditioners. He didn’t even have a fan!”

‘What do you think of Osama bin Laden?” I asked.

“What do you think of Abraham Lincoln?” he said.

When I had met General Musharraf earlier, I had asked him if he was not concerned about the Talibanization of Pakistan. For many of the madrassahs, although they had begun as religious schools that had educated, among others, the Taliban, they had by now, in a role reversal of sorts, begun preaching the Taliban’s ideology of militancy and jihad.

“Okay, okay,” the General had responded, slightly irritably. “I’ve never been to a madrassah, but I do know that all this talk about their teaching militancy is just hearsay. I’ve met with some of their leaders” (including Sami ul-Haq) “and they’ve said to me: ‘Who comes to the madrassahs? Has anyone from the Ministry of Education ever come? No. Only people from the police, from the intelligence agencies. We’re being treated as though we are dacoits (the legendary bandits of the Indian subcontinent’s ravines)!’”

So, I now asked Sami ul-Haq what he and his fellow Maulanas thought of General Musharraf.

“We had lots of hopes, but the poor chap has been caught up in a lot of problems,” he said. “He’s been very firm on Kashmir and, of course, that’s very good. But I wish he’d use the stick and clean up corruption and the politicians’ mess.”

“What would happen if he brought the madrassahs under government control or closed them down?” I asked.

“Impossible!” the Maulana said. “I asked him that question directly, and he replied: ‘Do you think I’m mad! The madrassahs are doing so much for the poor; you’re giving poor children free education, free lodging, free food. Why should I close them down?’”

Wedding guests had begun to arrive, so my interpreter and I said our good-byes. Before leaving, I asked the Maulana if I could meet some of his students, but al-Haqqania had just closed for semester break. As he walked with us to our car, one of the young men from the verandah explained that all of the students had left. Most had gone off to join some ten thousand other Pakistani volunteers, who were training or fighting in Afghanistan.

©2002 Mary Anne Weaver

Mary Anne Weaver, a foreign correspondent for The New Yorker, is reporting on Pakistan during her fellowship year. She recently signed a contract with Farrar, Straus & Giroux, based on her Alicia Patterson Foundation research, for her second book: “In the Shadow of Jihad — Pakistan, Islamic Militancy and the Taliban.”