The billboard signs along the roadways of northeastern Bosnia say it all. Superimposed on a map of the country is the outline of a key with “Brcko” on it. The old river city, historically a crossroads between Europe and the East, holds the key to the future of Bosnia. It is, perhaps, the only thing everyone here agrees on.

If Sarajevo symbolized Bosnia’s war, Brcko has symbolized its peace: the potential and the problems. What happens there next largely will determine the success or failure of the U.S.-brokered Bosnian peace accord – and whether war returns to the Balkans.

Brcko, the name of the city and surrounding district in northeastern Bosnia, sits on the banks of the Sava River separating Bosnia from Croatia to the north. Thirty miles east is the Drina River border with Yugoslavia. With its strategic road, rail and river links, Brcko was one of the first targets of the Serb-led Yugoslav army in April 1992 as it joined forces with local Serbs opposed to Bosnia’s independence from Yugoslavia.

Some of the earliest war crimes occurred in Brcko, whose ethnic Muslim and Croat residents – over 60 percent of the population – were rounded up and expelled from their homes, tortured in camps or murdered. Throughout nearly four years of war, the Brcko region bore the brunt of heavy fighting. But the city and roughly half the district remained under Serb control.

Impasse over Brcko nearly collapsed the November 1995 Bosnian peace talks in Dayton, Ohio. To preserve the deal, negotiators turned Brcko over to binding international arbitration. A final decision set for December 1996 was postponed until February. But with both sides threatening to take up arms if the other got Brcko, the American arbiter, who helped construct the Dayton accord, deferred until March 1998 his final decision. Brcko remains in Serb hands until then.

The hope is that civilian administrators of the peace accord can accomplish in the second year what eluded them in the first: a return of refugees to their homes in the Serb-controlled sector of northeastern Bosnia, centered around Brcko, and a political reintegration of the former battlefield foes. The fear is that Bosnia’s Serbs will remain intransigent and intent on separatism and that a rejuvenated Bosnian army – equipped and retrained by the United States – will at some point retake Brcko by force, unleashing a new wave of refugees and laying the foundation for an ethnically pure Bosnia. Interestingly, that is how Croatia, whose army was retrained by the same company of retired U.S. generals, dealt with its Serb minority in mid-1995 after years of failed U.N. mediation.

But an attack on Brcko, even a limited, successful one, would have dangerous long-term consequences.

“It would be a disaster because the only way that you’re going to maintain peace there is to have the Serbs and the Croats feel that they have a stake in Bosnia,” said a senior State Department official. “Bosnia is like a hinge which keeps some kind of machine together, and if you don’t have the multiethnic – however widely apart it is – Bosnia there, then you probably don’t have any true stability between Croatia and Serbia. They are both leavened in their behavior by the need to cooperate in Bosnia. Bosnia really is a key to keeping this whole very, very explosive region stable It is essential to the whole equilibrium of that region, which ultimately means the equilibrium of Europe.”

Nonetheless, one U.S. official involved in the Bosnian military retraining effort suggested it would be understandable if Brcko came to blows, given Serb refusal to implement the provisions of Dayton. And even the State Department official conceded that “maybe it’ll require a tragedy or a disaster” before Serbs start cooperating with the peace accord.

Bosnia’s ‘Neuralgic Point’

No less strategic in peacetime, Brcko connects the western and eastern flanks of Bosnian Serb territory like the knot in a bow. It is the choke-point along an east-west route in northern Bosnia, known as the Posavina corridor.

The Dayton accord divided Bosnia between a Serb republic and a Muslim-Croat federation under a loosely organized federal government with limited powers. Though the fighting stopped, the pre-war leaders and their pre-war aims have remained – separatism for the Serbs; Bosnian unity under a Muslim-led Sarajevo government for the Bosnians. If Serbs lost control of Brcko to the Bosnian federation, the Serbian Republic would be cut in two and hoped-for autonomy, if not later secession, likely would be lost. For that very reason, the Bosnians want Brcko. But the Muslim-Croat federation also argues that the Sava River port is crucial to markets and products in Europe and is its only rail-road-water center capable of meeting industry transport needs. More ominously, perhaps, Brcko also serves as an abject lesson in the spoils of war for the Sarajevo government.

By coincidence or plan, U.S. lawyer Roberts B. Owen, in postponing his arbitration ruling until March 1998, will decide the most explosive issue of Bosnia’s war and peace just as American peacekeeping troops are scheduled to be preparing to leave. Brcko is in the American-controlled sector, and U.S. troops went on high alert in February just in anticipation of a ruling. Owen gave the Serbs one year to start complying with provisions of the Dayton peace accord or risk losing Brcko to “special district” status of the federal government, even though its joint institutions do not yet function. Owen also requested an international supervisor be appointed to oversee Serb compliance. But with no powers of enforcement, economic reconstruction aid will again be the only leverage against the Serbs, who appeared unfazed at receiving just 2 percent of the $720 million spent on Bosnia in 1996.

What little progress there has been in resettling refugees and encouraging economic reintegration in the Brcko area during the first year of Dayton has been largely the result of creative U.S. military commanders carrying big sticks.

“The military side of this is a lot easier to do. You just bring in some fairly tough-looking guys with lots of heavy gear and you convey the impression that if you mess with us you’re going to regret it,” said Col. Gregory Fontenot, the commander of the 1st Armored Division 1st Brigade, which deployed in northeast Bosnia in December 1995. “Putting the guns in a box is a lot less difficult than rebuilding the country.”

Confronted with Muslims and Croats wanting to rebuild their homes near Serb-controlled Brcko but having no policy to guide them, Fontenot and Lt. Col. Anthony Cucolo – whose camp just outside Brcko was caught in a reconstruction war between Serbs, Muslims and Croats – helped write the book on refugee resettlement. The guidelines created for resettling their section of the NATO-run zone of separation between combatants became the blueprint for a program adopted for the rest of Bosnia’s 660-mile zone of separation.

“There’s no mission creep here,” Fontenot said, using the term that sets politicians’ and military leaders’ nerves on edge. “If there’s any creeping going on, it’s us. We’ve just got to be honest about it. No one’s asking us to do this stuff, we’re taking it upon ourselves because it works. Do what works.” The two officers ended their one-year duty tour in Bosnia late last year.

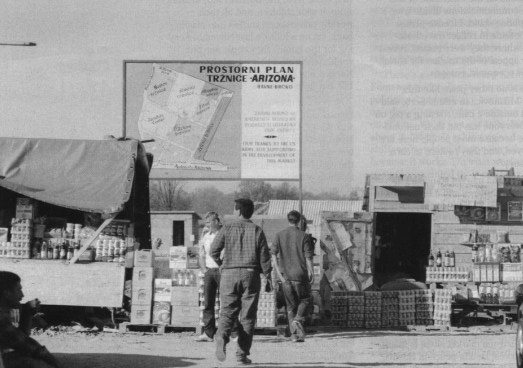

Arguably the American military’s greatest success in the Brcko area has had more to do with goods than guns. Shortly after NATO troops put Bosnia’s armies back in their barracks, an impromptu black market sprang up along a major north-south road that intersects the Posavina corridor en route to the Sava. It grew so fast, attracting Serbs, Muslims and Croats from around Bosnia and Croatia, it quickly became a hazard to military logistics and life, as it spread into fields that were still mined. The U.S. military helped de-mine the area, leveled fields and installed a drainage system, and the so-called Arizona market (named for the military’s Route Arizona along which it lies) now sprawls over the equivalent of six football fields. It generates an estimated 100,000 German marks of business a day, much to the chagrin of separatist politicians on all sides, who would like to see the market shut down or at least taxed.

U.S. troops just across the road from the outdoor market, manning a checkpoint on the former front line, are sometimes called in to quell trouble. But their commanders see that as consistent with Dayton’s mandate to create an overall secure environment in which peace can flourish.

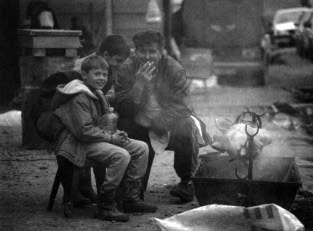

Most anything can be had at the Arizona market, from Levi’s 501 jeans and perfume to kiwis, car parts and livestock, and often at prices far lower than elsewhere in Bosnia. Weary shoppers stop for coffee or specialty meat dishes at any one of scores of cafes, cobbled together from plywood and warmed by kerosene heaters, and can even make calls to those on the other side of the land line communications divide from a cellular phone stand. License plates, which continue to reflect the ethnic majority where they were issued, reveal the wide appeal of the market for social, as well as economic, reasons.

“There is no other place like this,” Milenko Milanovic, an ethnic Serb, said as he sat outside a cafe, roasting a pig on a spit. “Everyone has put their nationalism aside because most people here are unemployed, and they’re here to earn some money.”

Above Arizona market stands a billboard grid of the area and a few words of thanks “to the U.S. Army for supporting in the development of this market.”

“The linchpin to success in the Posavina (corridor), and possibly Bosnia, is the integration, economically and socially, ofBrcko,” Fontenot said. “It won’t matter what we do with the armies if you don’t rebuild the country.”

Refugees and War Criminals

But the Arizona market alone is insufficient to harvest lasting peace in Bosnia, as High Representative Carl Bildt, the senior civilian official, reminded Bosnians on the one-year anniversary of the peace accord. “You can’t rely on the black market being the one unifying force in the country,” Bildt said last November. “Most of the agenda remains to be fulfilled.”

He said 1997 would be the key year for dealing with aspects of the war not yet addressed: the return of Muslim, Croat and Serb refugees to their homes and the arrest of indicted war criminals.

No two issues in Bosnia are harder to resolve.

The basic contradiction of the Dayton peace accord is the right of refugees to return home in a country where the laws of two separate entities prevail. Aside from the NATO-ruled zone of separation, refugees wanting to return home in territory controlled by the other side are dependent on the goodwill of that side. With political leaders who want separation – mostly, but not exclusively, the Serbs – that goodwill does not exist.

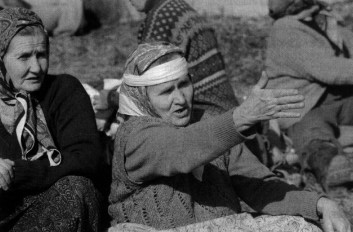

Gajevi, a zone-of-separation village southeast of Brcko, is a case in point. In a scene from the Bosnian war, Muslim women with children, and all their worldly possessions stuffed into plastic bags, sat on a hillside last November crying for the homes they could see but could not reach. Their homes were in Koraj, a few hundreds yards down the hill, but fully inside the Serb republic.

Played out over several days, the scene turned ugly when Serb police clashed with Muslim villagers. Two people were killed, several others injured, and U.S. troops got caught in the cross-fire. In the end, NATO commanders accused Bosnian officials of organizing the attempted return home, alleged a military presence among the villagers and destroyed a cache of legal and declared Bosnian weapons as punishment. Trouble repeated itself in January, when a Serb mob attacked a group of Muslim villagers who had received international permission to rebuild in Gajevi, and again in March, when Serbs burned down Muslim homes under reconstruction in the NATO-policed zone.

“We’re trying to cooperate peacefully, but if not we’ll find another way,” said Novalija Karasuljic, a Koraj native who joined hundreds of other protesters in November demanding that international officials make good on Dayton’s promised homecoming.

His neighbor, Ismet Mojidzic, was more blunt: “If we can’t go back home, then we’ll have another war.”

The mindset that rules postwar Bosnia is so similar to the one that fueled the fighting because the same actors are on stage. The former Serb military and political leaders, Gen. Ratko Mladic and Radovan Karadzic, still wield enormous influence. And the fact that they have moved about Bosnia with impunity despite an international arrest warrant on charges of genocide and the presence of tens of thousands of NATO troops has only added to their stature in the eyes of many.

“I think we could have accomplished more in the last year than we did had the NATO forces been willing to be used more actively,” former Assistant Secretary of State Richard Holbrooke said in assessing the implementation of the peace accord he crafted. “There are many areas where there was a shortfall. The most visible one was the failure to take action to even attempt to detain and arrest some famous war criminals. We didn’t even try it in the last year, and I think that was a huge mistake.”

Nothing triggers an argument faster with NATO commanders, particularly American ones who recall the casualties of Somalia, than the debate over arresting indicted war criminals. The Dayton accord gives NATO troops the authority to detain war criminals should they encounter them in the normal course of their duties. But even when that has occurred, no action has been taken.

Not until July – 18 months after NATO deployed to Bosnia – did troops (from Britain) move against accused war criminals, arresting one and killing another in a shootout after he resisted arrest. But Karadzic and Mladic remain free.

“We’re not the Mod Squad; we’re the Army,” said Maj. Gen. William Nash, who commanded U.S. forces in Bosnia during the first year of Dayton said late last year. “I don’t do individuals. I do armies.”

Of the 77 people indicted for war crimes by the international tribunal at The Hague, only about a dozen are in custody. Military officials make a good argument that hunting down war criminals would undermine the kind of trust necessary to do their jobs. Yet NATO troops are the only ones equipped to make the high-profile and possibly risky arrests so necessary to a sense of justice for all Bosnians and an elimination of collective guilt for the Serbs.

“In general, the military task of separating the forces and maintaining a zone of separation between the entities has succeeded completely,” said Marshall Harris, a State Department officer who resigned in 1993 to protest U.S. Bosnia policy and later co-founded an influential Bosnia lobby group. “The problem is that none of the provisions in Dayton for reintegrating Bosnia has succeeded.”

The Action Council for Peace in the Balkans originally opposed the U.S. troop deployment to Bosnia, fearing it would cement partition and legitimize the territorial gains of a genocidal war. It publicly supported the mission only after then-national security adviser Anthony Lake made an “express commitment” that war criminals would be arrested, Harris said. Those attending the meeting said they understood that to mean arrested by U.S. troops, though in retrospect that was not spelled out.

“It is my clear impression that I have been lied to twice, and one of those times by the president of the United States, that there was an intent to bring these people, most especially the Bosnian Serbs, to justice,” said former assistant secretary of state Hodding Carter III, a council member who attended meetings with Lake and President Clinton, said in an interview earlier this year.

Short-term Goals, Long-term Hopes

In convincing the American people to support the Bosnia troop deployment, the Clinton administration also said it would use the time to help equip and train Bosnian federation forces so there would be a credible counterweight to the Serbs that would allow U.S. troops to come home sooner and prevent future war. The same argument was used on the Bosnians to get them to accept a peace deal they believed made too many concessions.

Richard Perle, a former U.S. assistant defense secretary who has been a military adviser to the Bosnians since the Dayton negotiations, said the Bosnians would not have signed the peace accord without the equip-and-train pledge. But the program has since become “too feeble an effort,” said Perle, adding he suspected the administration’s commitment to the program first when it refused Bosnian requests to incorporate it into the text of the peace agreement.

A February 1996 report for the administration by the Institute for Defense Analyses estimated that a program to meet Bosnia’s defensive needs would cost about $700 million in its first stages. The program which finally got underway has a $200 million budget. Half of that value is in older, refurbished U.S. military equipment given to the Bosnians. The other $100 million, donated by Muslim countries, is for training and additional weapons systems. The first year’s training contract with

Military Professional Resources Inc. of Alexandria, Va., costs $40 million, and officials say a second year of training will be necessary. If no more donations are forthcoming, the Bosnians will have only about $20 million to augment weaponry not included in the U.S. package.

By comparison, the cost of the U.S. deployment is expected to total $7.7 billion, according to the latest government estimates.

European allies opposed the equip-and-train program from the start, fearing the potential of a sophisticated, largely Muslim military in their midst. To ameliorate such concerns, the United States sought donations only from “friendly” Muslim countries. It also refused to begin the program until Sarajevo fired two government officials and cut its military ties to Iran – which shipped arms, with U.S. approval, to the Muslim-led Bosnian army through most of the war.

“It’s been an appalling failure to meet our commitment,” Perle said. “My best guess is that there will be a resumption of fighting after the U.S. withdrawal; that equip-and-train will not succeed in establishing a military balance.” Perle argued that a weaker Bosnia will remain a target for attack, but he also acknowledged the Bosnians “have been pushed around” and are “likely to be the least satisfied with the status quo at the point at which we leave.”

U.S. military commanders in Bosnia also note it is the Muslim-led army which speaks of revenge, and it is here that the frustrations over refugees, war criminals and equip-and-train converge.

“Clearly the administration’s policy is we will do what it takes to prevent a short-term renewal of fighting,” Harris said. “The problem with that is that it may ultimately backfire. The things they’re doing now to prevent a short-term outbreak creates great resentment on the part of victims, and it may be that the whole thing blows up again because of these short-sighted policies.”

Another glitch in the equip-and-train program is that while its premise is the union of two armies – one predominantly Muslim, the other ethnic Croat – they don’t have to merge forces until 1999. The program was supposed to strengthen ties in the creaky Muslim-Croat federation, but the soldiers do not train together.

The Croat hot spot equivalent to Serb Brcko is Mostar, a southwest city where normally bad blood boiled over in February when Croat gunmen attacked a group of Muslims. Despite the tensions, Mostar is not likely to be the immediate threat because it does not have the strategic importance of Brcko, and because the Muslims still needs the Croats – no matter how much trouble they cause in Mostar – as long as the Serb problem is unresolved.

Mirsad Djapo, the deputy mayor of Muslim-Brcko, has dreams for the city, and wants it to be a model for the reintegration of Bosnia-Herzegovina. “The destiny of Bosnia will have everything to do with what happens in Brcko,” he said.

For different reasons, others agree.

“Unless the Americans use massive pressure on the Serbs, including the possible use of force – very unlikely – the Brcko decision will remain unimplementable,” said an international official in Bosnia, on condition he not be named. He predicted the Serb leadership would be exposed in the coming year as an obstacle to any solution for Brcko, and thereby Bosnia, and said the future looked bleak. “In the summer of 1998, a quiet green light will be given to the federation to enforce Dayton militarily.”

©1997 Maud Beelman

Maud Beelman, a foreign correspondent for the Associated Press, examined U.S. foreign policy in the former Yugoslavia during her Patterson year. She is now based in AP’s Washington bureau.