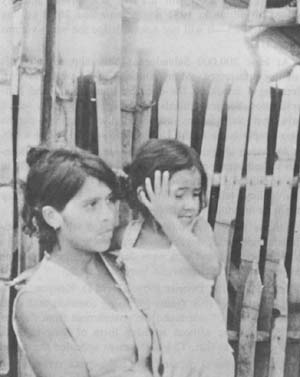

COLOMONCAGUA, Honduras–”We ran like animals,” said Claudia Garcia, 19, who, with her three-year-old daughter recently arrived at this sprawling refugee settlement housing more than 6,000 people.

In mid-May, her group of 46 campesinos left northern El Salvador fleeing a government offensive to drive guerrillas out of the area. For 22 days they trudged through soggy tropical forests, scrounging fruits and killing wildlife. Eventually the group grew to 200 people-men, women, children, grandparents-who moved toward the border, stopping to bury a young mother and her newborn child.

The civil war in El Salvador is its single most important demographic catalyst since the Spanish Conquest. At least 200,000 Salvadorans are displaced; about 40,000 have died in the last three years; approximately half a million others-more than 10 percent of the population-are scattered from Canada to Panama. Almost all cross their city limits for the first time as they straggle reluctantly in an exodus to uncertain foreign hospitality. According to estimates from the United Nations High Commission for Refugees (UNHCR), 40 per cent die on the way.

Several weeks ago a lone rider, a blue-and-white UN banner fluttering atop his staff, made his way gingerly down the recently-worn trail on the El Salvador-Honduras border. He was one of three UNHCR officers patrolling by horseback and jeep along 200 kilometers of contested frontier where hundreds of refugees have died in the past two years.

Huddled in the tropical growth, refugees watch for the banner’s rippling signal ending the exhausting trek through battle zones toward a refuge they know only by word of mouth, said to be lying somewhere east of the besieged towns they flee. Since mid-June, UNHCR roving officers have led more than 600 people to safety.

Five of the six Central American nations recognize immigrating Salvadorans as refugees; Guatemala does not. Three nations-Panama, Costa Rica and Nicaragua-signed the 1951 Geneva Convention and its 1967 amendments which define refugees as those persons who for reasons of race, religion, nationality or political opinion have a well-founded fear of persecution should they return to their countries. The agreements also forbid deportation, establishing guidelines for refugee protection in host nations.

In the United States, another kind of reception awaits homeless Salvadorans. U.S. Border patrols, aided by high-powered technology, scan the U.S.-Mexico border, seizing those discovered for possible deportation. Although the Reagan Administration recognizes the civil war in El Salvador with massive amounts of military aid–$26 million in 1981 and a requested $61.3 million for fiscal 1983–it will not acknowledge the war’s victims in the U.S.

At least 200,000 Salvadorans have slipped into this country undetected. Many continue to lie awake in fear, dreading a knock on the door by Immigration and Naturalization Service officials enforcing U.S. policy, which says that Salvadorans are economic refugees-people who simply come to the United States in search of a job.

American church and citizens groups protest the Reagan Administration’s stand on refugees. The UNHCR in the spring of 1981 privately criticized the U.S. deportation policy, telling Washington officials that the policy might be in violation of international law.

Of the more than 6,000 Salvadorans who filed petitions seeking U.S. asylum in fiscal 1981, only 154 were considered. All but two were denied. During the same period, 10,473 Salvadorans were deported.

Last May, U.S. District Judge David D. Kenyon, in an order criticizing INS agents for using coercion and even “physical abuse,” restrained the government from deporting Salvadorans without advising them of their right to seek political asylum. The government appealed the order.

In U.S. political rhetoric, the Salvadoran refugee is a job threat and a social service drain. Only a patchwork of church-sponsored organizations, citizen groups and volunteer workers aid refugees. These groups offer an institutional skeleton of community-the only safe assistance and psychological nurturance in an otherwise threatening society.

“Early in 1981, the need to help Central Americans became apparent to us,” said Gene Boutelier of the Southern California Ecumenical Council. “At a meeting to discuss these matters, the Interfaith Task Force on Central America was created. It now numbers about 150 groups and individuals who have dedicated themselves to different Central American needs.”

“On the one hand, it’s terrific what people are doing,” said Rev. Alice Callaghan of Pasadena’s All Saints Episcopal Church and a member of Concerned Church Women, which opposes refugee deportation. “On the other hand, it’s such a small drop in the bucket of need.”

The UNHCR extends both financial and administrative assistance to any country requesting help to provide for refugees. The aid usually goes to countries of “first asylum,” the first final destination of the refugee.

For the past 30 years, the United States has contributed at least 25 per cent of the annual UNHCR budget. In 1981, the national contribution was specifically increased by $7 million for Latin American use: $5 million for UNHCR discretionary use and $2 million for aid to Salvadoran refugees in Central America.

In granting aid to sheltering countries, the UNHCR tries to move quickly toward “durable solutions”-measures that will assure refugee self-sufficiency either collectively or individually by helping refugees set up small businesses or agricultural projects.

Our efforts must fall within existing national economic and job-producing policies and must contribute to the growth of the host country,” says Philip Sargisson, regional representative of the UNHCR, based in Costa Rica. “At the same time, projects must be labor intensive, substitute imports and avoid displacing local labor; they must be socially beneficial and provide training.”

“To meet this criteria, we send in an interdisciplinary team of economists, social workers, psychologists, lawyers and other professional advisors. In countries like Costa Rica and Belize, where unemployment is high, we are working with government support on projects that will involve both refugees and nationals.”

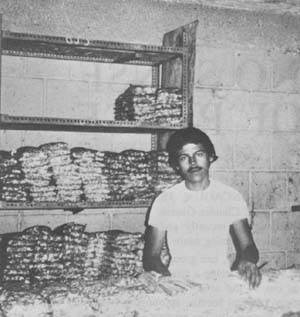

In Costa Rica, Salvadorans are automatically recognized as refugees. Fifty-nine urban and several rural projects are underway. One is the candy factory in San Jose where crinkly bags of gaily colored candy line up like sentries along the back wall of a modest building-a salute to Salvadoran enterprise, UNHCR financing and a benevolent government.

The factory employs 15 heads-of-household supporting 150 people who live in regular neighborhoods throughout San Jose. “We are used to paying our own way,” says Jaime Diaz Rivera, 20, one of three Salvadorans who earlier submitted a small business proposal to UNHCR for funding. His parents and six brothers fled El Salvador more than a year ago.

“We had never been without work before. My parents owned a small store,” he said. “None of us was politically active, but the military ransacked the store over and over again, taking whatever they fancied and destroying a great deal more. Others in our town were killed without reason. We had to leave.”

Tucked into small neighborhoods around San Jose, behind shiny glass windows or non-descript walls, other doors open to budding economic security for Salvadorans. “They are respected throughout Central America as the most resourceful and industrious people,” said one UNHCR official. “When they were expelled from Honduras during the 1969 war, that country’s economy collapsed.”

Across town from the candy factory, school uniforms keep 220 Salvadoran refugees economically independent. “I’ve never done anything like this before,” said Gilbert Funers, the promoter-manager. A former government office manager earning a business degree at the university in San Salvador, Funers fled his country 18 months ago. “Students are the ënatural enemies’ of the regime, according to the military,” he said. “It just got too dangerous to stay even though I worked for the government itself.”

A former secretary, a factory worker, a student and a housewife are among the eight women who now operate sewing machines. They are the sole support of their households:

“My husband’s project has not yet been approved,” said one woman worker. “So, for the moment he does the housework.”

“Mine too,” said another. “And is he ever looking forward to getting an outside job, but child care will be a problem then.”

So far, UNHCR urban projects do not include child-care centers, but since Salvadoran refugee families live all over the capital, logistics for such a plan could prove difficult to implement.

Far outside the urban sites lie Costa Rica’s rural projects. Nestled within fertile fields miles from the closest small town or main road, they seem to force isolation on the small refugee enclaves.

In Guanacaste, Costa Rica, down a narrow dirt road shaded by banyan trees, whose roots hang down from outspread limbs to push against the red earth, a small sign marks the entrance to the Los Angeles settlement. Purple, green and yellow fields checkerboard across cultivated rolling hills around camp offices, schools, workshops, communal kitchens and dining rooms, livestock sheds and barracks housing.

Organized in November, 1980, to accommodate the 216 Salvadorans flown there after they sought asylum in the Costa Rican embassy in San Salvador, the model 191-hectare ranch now supports 400. Land for three more such ranches is under negotiation.

“We are developing our own infrastructure,” said Manuel Castro, associate program officer of the settlement. “Salvadorans built all the buildings. They do all the work here. All the decisions are made by their own elected committees, including the decision to hold community-earned spending money down to $200 colones (about $4 U.S.) a week per household.”

Down the road, visitors shared a meal with refugees, crowding around the oilcloth-covered table to dish up food raised on the ranch. Chicken and rice with garbanzo beans, tortillas, salad, beans and plantains were piled up on the plates. Nearby, workmen hammered together single-family prefabricated homes built by a Costa Rican company.

“It is still a struggle to get refugees to eat vegetables,” said the clinic’s doctor. “I am constantly prescribing them to my patients. But the most severe problem here is depression, especially among women. Many have left members of the family behind or have seen them killed. There is no way to lift them out of their thoughts, no diversion. I try to get them to talk. Too much is bottled up inside.”

Asked about women’s activities, one UNHCR official looked surprised. “The women have their homes and their children,” he said. “And in the evening there is chapel. These are very religious people.”

“What I’d really like to do is be able to go to town,” said Maria Ginaro Claros, 50, her dark eyes focusing on the hills outside.

“Back home, my friend and I,” she slipped her arm around the blue-eyed woman standing next to her, “went to town together. We were just housewives then and next-door neighbors. We liked to go to town and browse, to see other people. In chapel you begin to think of all the other people you have known and all the things that happened. It makes you very sad.”

“I’d like to get a pair of sandals,” said Olga Marina Argetta, a widow whose six children were killed by Salvadoran soldiers before she fled to the Costa Rican embassy. “Or just go to town like we used to.”

“We’ve been friends since the first grade,” added Ginaro, whose husband also made it to safety in the embassy. “When I finally got here to join him and found Olga here too, we asked to be neighbors again.”

But their experience is rare. Most refugees find themselves in artificial communities without old friends or familiar faces. The loss of community compounds the trauma of personal loss. Acute depression is pervasive among refugees, even in the best of material conditions.

On the other hand, nutrition is greatly improved and the doctor reports no infant mortalities or mother’s death in childbirth. “The most common physical problems are respiratory diseases,” he said. “The change in climate is hard on these people.”

In Nicaragua’s resettlement camp at Leon are others who knew one another before leaving El Salvador. More than 160 people sought refuge in a church basement in San Salvador, where they lived until last April when arrangements could be made with the government there to evacuate them.

In Nicaragua’s resettlement camp at Leon are others who knew one another before leaving El Salvador. More than 160 people sought refuge in a church basement in San Salvador, where they lived until last April when arrangements could be made with the government there to evacuate them.

“We were in the basement for more than a year,” said 19-year-old Maria Magdelina Herrera, mother of three. “The baby was born there. This is the first time many children have breathed fresh air or played in the sunlight.”

“About 150 youngsters attend classes,” said Josefina Perez, the camp school teacher. “But it is an awful struggle. We’re very short of materials. Mostly I draw what we’re talking about on the board and they copy it. We need social science readers and grammar books. I wish we had a globe-the children have no sense of place.”

Behind the one-room school, on a cement slab patio, four women bustle about in early dinner preparations, their arms barely reaching the bottom of huge black pots in which they stir beans.

“We all cook,” said Anna Fidelina Tristole, 25, coaxing a reluctant fire, “except the women who are sick or very depressed. We take turns. But soon I will be moving to a cooperative and someone will have to take my place.”

Refugees in Nicaragua

“Nicaragua has been very generous to the refugees,” said the UNHCR’s Sargisson. “They are allowed to take employment and to move freely about within the country.” Thus, according to the UNHCR, most are able to find their own solutions to the problems of self-support.

Although the Sandinista government estimates that more than 22,000 refugees live in Nicaragua, only about 3,000 are “hard core” dependents. Rural long-term projects are being organized to ease their situations, according to government officials.

Outside Leon, just beyond a bridge lying twisted on its side in the wake of tropical storm Aleta, one of the first rural cooperatives is hoping to harvest its first crops this year.

As soon as the Sandinistas and the UNHCR can work out property ownership questions, prefabricated homes will be erected for refugee families there. Meanwhile, the families live in a single wooden building, cooking outside at one end of a roofed-over piece of muddy ground.

Three shy preschoolers, led by a chatty five-year-old, walked visitors to the fields in search of their fathers. “We had a lot of rain,” said one straw-hatted youngster as he surveyed the muddy storm damage. Aleta dumped more than 12 inches of rain daily for six days on Nicaragua, doing $200 million damage and leaving from 60,000 to 80,000 people homeless. The storm was far more devastating than the famed 1972 earthquake which leveled much of the capital city, Managua.

“Salvadorans receive the same social aid as Nicaraguans,” said Reinaldo Antonio Tefel, president of the Nicaraguan Social Security Institute, which coordinates and implements assistance programs. “They are treated just the same, and will receive assistance because of the floods from Aleta.”

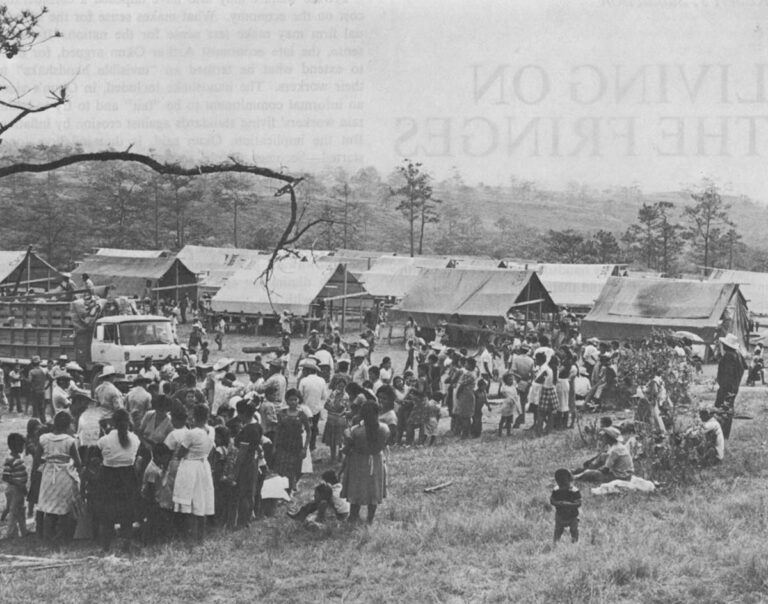

Tropical storm Aleta also wiped out a major bridge near Mesa Grande, Honduras, forcing the 38.2 tons of food which must be trucked weekly to more than 8,300 refugees into a circuitous detour through Guatemala. Food shortages are now common.

There have been other troubles at Mesa Grande. Isolated atop a broad, remote plateau outside San Marcos, where hot days and brisk nights amidst infertile, pine-covered hills contrast with their familiar tropical environment, the refugees say they feel stranded and confined. Many will not agree to a proposed relocation move still further inside Honduras. Most have already been moved once from border sites, where Honduran and Salvadoran military spokesmen charged that refugees were slipping food to guerrillas. Refugee spokesmen deny the allegations.

The refugees moved reluctantly to Mesa Grande after administrators promised better facilities, social services and safety. Transported suddenly and prematurely by the Honduran military, they arrived to find no established water system, no erected shelters and insufficient clothing for the mountain climate. Credibility has never been fully restored. Refugees also mistrust the military of both countries.

“How can we trust them?” asked a refugee spokesman. “How can we trust the Honduran army whom we’ve seen cooperate with the Salvadoran soldiers? We don’t want to be any further inside and dependent upon them. We want to be close to our own country.”

The camp’s pole and thatch huts show the wear of daily use. Hammocks are strung in the crowded aisles between shelters where most of the daily chores are done. Mothers sing lullabies under the trees.

“Everyone has worked hard getting this place started,” said one young mother, juggling two toddlers on her lap.

“No one wants to start all over again. And the children have just gotten used to this place.”

No matter where they go, a refugee’s life is painful, even under the best conditions. They live in contrived communities devoid of their former communal niche, which reinforced personal identity.

Acute depression is the norm. Most have lost family or friends. Once self-sufficient adults now live in controlled communities, unable to make even the smallest independent decision about their lives. They are generally suspended from a money economy.

“Once in a while, I’d like to buy a mango,” says one elderly man. “It’s not a big thing, but I’d like to know that I could.”

Women suffer even more. Few refugee policy makers are women in Latin societies and most men overlook women’s needs or define them within narrow stereotype. Planners seldom ask refugee women about home construction or design, but they talk to men about their work habits. Soccer and baseball equipment is quickly provided for males; recreation for women is rarely considered.

The absence of toys is also marked at refugee camps. Currently, no project proposes to produce toys.

Refugees headed for the United States face even more severe trauma. They arrive bedraggled in Los Angeles, 3,000 miles after crossing San Salvador’s city limits. Few leave there with any realistic knowledge of what awaits them, either on the trip or once they arrive exhausted in the urban sprawl of Los Angeles.

One woman described her trip to the United States. Her story, and those of other refugees, are shadowed by vulnerability and victimization.

“On both sides of the Guatemala-Mexico border at Talisman, they take everything they can find,” said the young mother of two daughters. “Women are strip-searched. What the Guatemalans don’t find, the Mexican authorities do.

“Tapachula, Mexico, is very bad. By the time I reached mid-Mexico, they had taken everything of value I had with me. The last official handed me back three pesos. ëFor milk for the little ones on the way,’ he said.

“A Mexican bus driver bought us tickets for the next lap. By the time I reached Mexico City, I was desperate. The baby was crying from hunger. We were tired and cold. Once I just leaned against a lamppost and cried. A Mexican woman, passerby, handed me 200 pesos and a piece of material to wrap the baby in.

“I never planned to come here. I used to sell food and used clothes at a stall in the market, but the military was always searching the market, taking people away they said were subversives. No one could even give a bite of food to a hungry young man without risking their lives.

“A young woman vendor, a friend of mine, was gunned down at the market door. No one knew why. I gave up my stall, sold all my things and got on the bus. After I got here I heard that the soldiers were looking for my husband. My children were left alone, being cared for by neighbors. I went back for them. I’ve never heard any more about my husband.”

Down the street from the squalid building where the young mother now lives in Los Angeles, a middle aged couple and their children hide from the Immigration and Naturalization Service.

“First, we sent our son out of the country,” said the woman. “He is 22, a teacher. The soldiers are killing a lot of teachers. He went to Guatemala first. We had no intention of leaving. We had our grocery store; my husband, his carpentry shop. We owned our little house and two others.

“But so many were killed. I began to help prepare bodies for burial…so many children. There just seemed to be more and more dead. Then the priest told us our names were on the death list. We couldn’t believe it. We had done nothing. But he gave us the names of others listed. One by one they were killed. My husband left first.

“You could lie in bed at night,” said her 13-year-old daughter, “and listen to the machine guns in some neighbor’s house. You could hear footsteps outside the window. Once on the way home from school we passed a friend’s body all shot up.”

The family grew quiet as a local Spanish-language television gave news of El Salvador. They wanted to go home, they said. Familiar countryside and fellow Salvadorans on the screen made them homesick. In the mean time, they keep a low profile. Only one parent leaves the house at a time.

“The children have seen too much,” said the mother, smiling at her four-year-old hiding behind a chair. “Sometimes I clean houses, but when my husband works, I take care of the two little ones here. That way our children will never find themselves alone in this country with their parents picked up in a raid.”

In Los Angeles, the largest expatriate Salvadoran population in the United States strives to live invisibly.

To the casual observer, restaurants give the first indication that a new society grows within the outlines of the old. “Papusas” (tortilla-like food), “Yuca con frijoles” (tubers and beans), and other bright signs shout over refugee fear. “Mexican and Salvadoran food,” say freshly painted cafe windows. Inside, Salvadoran appetites stimulate Latino entrepreneurs who lay out broader menus. Customers speak musical Spanish in slightly different cadence.

A loose coalition of agencies struggles to provide an institutional framework of relief and social service centers. Tucked into church buildings and store fronts, hidden in dirty alleys and shabby cellars, groups of citizens help Salvadorans job search, look for housing, raise bail bond money or acquire food and clothing. Behind desks cluttered with papers, overworked young lawyers also erect paper barriers between worried clients and the INS.

Last year, the Interfaith Task Force on Central America founded an agency called El Rescate (The Rescue) to help Salvadorans with legal assistance and social services. Refugees help to staff the organization.

“El Rescate is growing,” says Gene Boutelier of the Southern California Ecumenical Council. “We intend to help these people until they can help themselves. Until they can find funding from other sources. They might turn to the United Way, if it weren’t so busy funding ideas from the past century.”

Instant Poverty

Such assistance is desperately needed. Most Salvadorans are plunged into instant poverty here without familiar support networks. Refugees hiding in a strange new country cannot safely market skills that were valuable in El Salvador without refugee status.

Many join a growing Latino community on Skid Row, a stark, industry-laden corridor of 50 blocks east of the central Los Angeles business district. Salvadorans and undocumented Mexican families squeeze into dingy, ill-kept hotels which once solely catered to derelicts.

Most of these Latinos hope to better their lives through upward mobility. Salvadorans eye the Alvarado district to the west, where there are stores, restaurants, churches and homes with grassy front yards. Trees, flowers, and front-step conversations lend neighborhood warmth.

It is an area where information networks are easier to plug into; patterns of exchange have been established for some time. Handbills and posters are frequently slapped on utility poles and graffiti-splashed walls. The easy park bench and street corner chatter of longtime Spanish language residents invites a newcomer’s participation.

El Rescate is in the Alvarado district. Its new self-help group, Santana Chirino Amaya (named after a young Salvadoran deported from Los Angeles to El Salvador, where he was killed) was organized last December. Now, more than 50 members are trying to implement its first project: a janitorial service.

“They’ve acquired all the equipment already,” says Gillermo Rodezno, social service coordinator at El Rescate. “They simply lack transportation. We’re all trying to raise money to buy an old truck. Then, they can start working.”

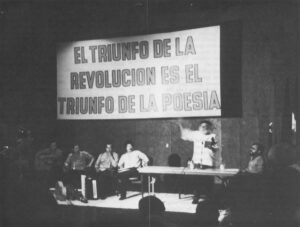

Several blocks down the street in a small dingy basement lighted by two bare bulbs is Casa El Salvador, the cultural arm of the community. Here, earnest young adults plan lectures and stage street theater. A handful of folk singers practice Nuevo Canto, or songs of resistance, revolution and renewal-their voices bouncing off the cement walls.

The songs are familiar throughout Central America. Sometimes in the evenings, Radio Venceremos, the clandestine guerrilla radio station in El Salvador, plays them. A few miles away, they are heard here in Colomoncagua, where a man sits quietly making hammocks, his hands steadily weaving rose threads through red and blue strands stretched taut between two upright poles.

Last year the hammock weaver might have lived next door to the candy maker in Costa Rica or the frightened domestic worker in California. They might have all attended the same whitewashed church before they too slipped away in the night like so many others, steadily emptying the villages of El Salvador.

“I just want to go back home,” said a young widow, who has five children under seven years of age, and now lives in a Nicaraguan cooperative.

The wish is repeated over and over again, from Los Angeles barrios to the fertile green hills of Costa Rica.

©1982 Mercedes de Uriarte

Mercedes de Uriarte, assistant editor of the Opinion Page on leave from the Los Angeles Times, is studying social change in the U.S. and Central America.