Photos by Jeffry Scott

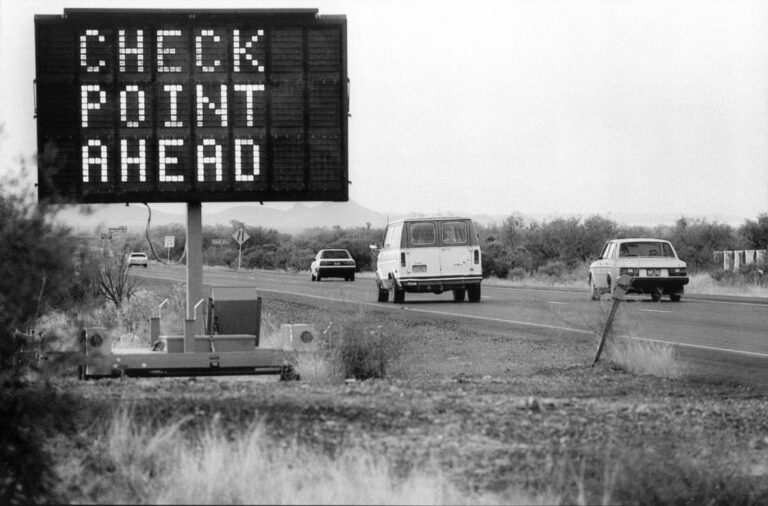

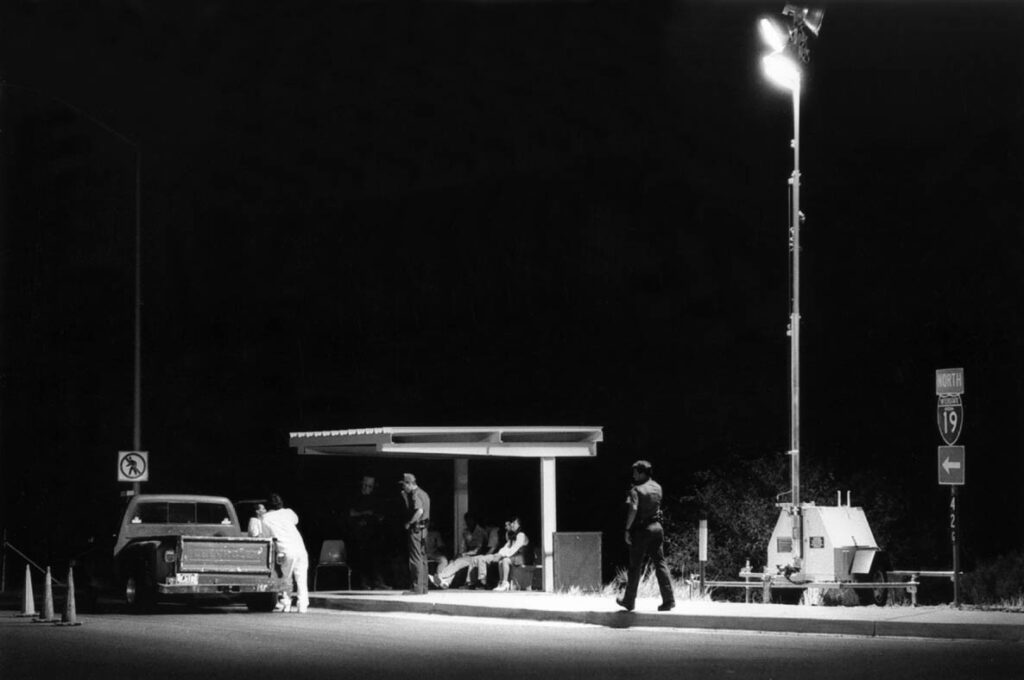

A spring shower has just ended, and as the sun sets over southern Arizona, five United States Border Patrol agents work quickly to reopen a traffic checkpoint on the main highway north from Nogales. The checkpoint, which is taken down during bad weather to prevent accidents, has been closed for about an hour.

“The smugglers know when the checkpoint is down, and that’s when they send their loads through,” says agent Sonya Ealey, as her fellow agents place cones and signs on Interstate 19 to divert traffic up on to an overpass. “We always catch a bunch when we reopen after being closed for a while.”

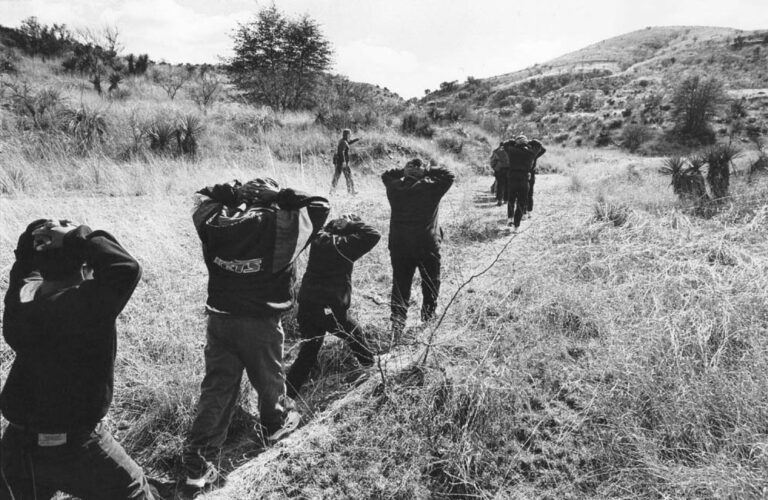

Sure enough, after a little more than hour, eight illegal Mexican immigrants are standing by the roadside, waiting for a ride back to the border. All of them have been plucked from the passengers in taxis and shuttle vans that run between Nogales and Tucson, 60 miles north.

But a small, dejected group of aliens isn’t all the agents catch this evening. They also catch flak from dozens of local residents who are angry about being stopped and asked for their citizenship. Some people roll their eyes or flash dirty looks. Others express their displeasure by speeding away from the checkpoint in a squeal of tires. Ealey and the other agents say drivers honk, yell, and curse at them. They have been called “Nazis.”

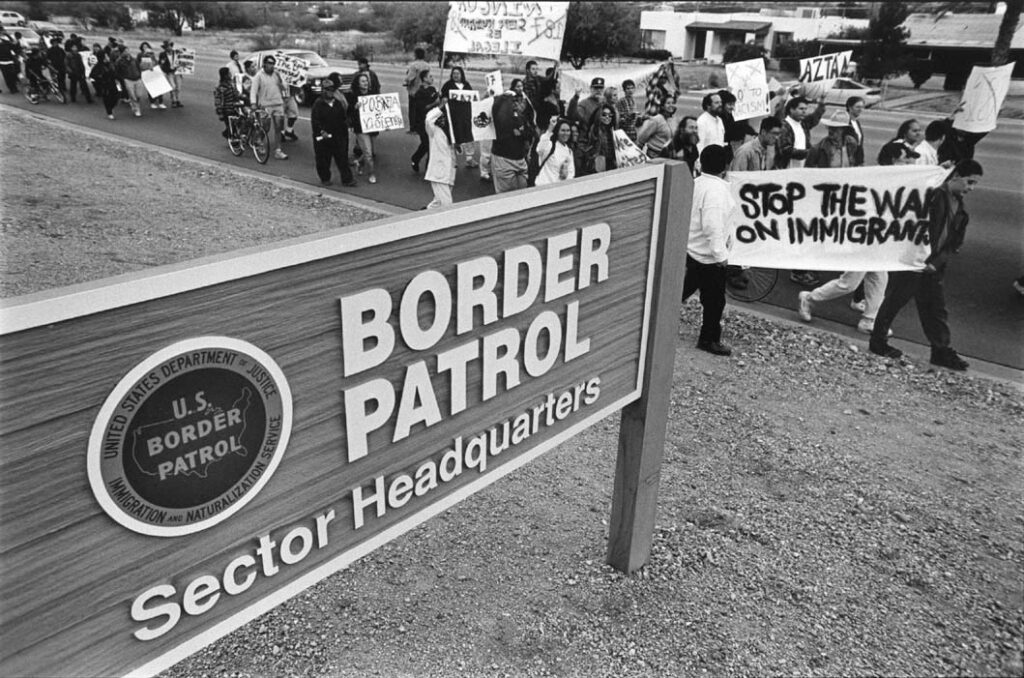

Some opponents of the checkpoint, which sits about 30 miles north of the border near the town of Tubac, are doing more than venting their anger at agents. They have gathered signatures from hundreds of residents and convinced political leaders that the checkpoint is wasteful, inefficient and unfair. Last April, opponents scored a major victory when, with the help of Arizona Congressman Jim Kolbe, they succeeded in getting a House subcommittee to cancel the construction of permanent facilities for the checkpoint. The decision leaves the Border Patrol’s Tucson sector, which covers the entire Arizona-Mexico border except for the Yuma area, as the only sector on the Mexican border without at least one fixed checkpoint.

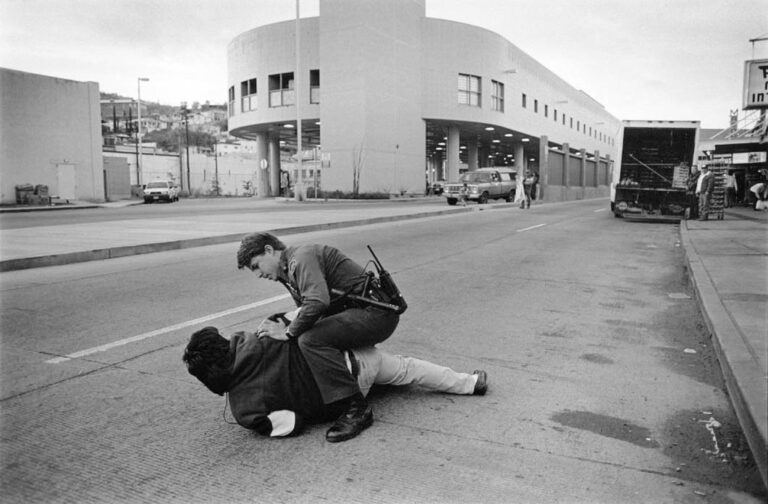

The opposition to the checkpoint heralds a small but growing backlash against the recent, unprecedented buildup of the Border Patrol in southern Arizona. Although most residents say they support the Border Patrol’s efforts, many also are concerned about violations of their civil rights and, they say, the “militarization” of their communities.

The controversy raises questions about how much liberty Americans are willing to give up in order to crack down on illegal immigration.

Since October, 1994, the number of Border Patrol agents in the Tucson sector has tripled, from 287 to more than 900. The buildup in Arizona followed previous ones in the El Paso and San Diego areas, and a similar effort is now underway in the Rio Grande Valley. Nationally, the Border Patrol budget grew from around $362 million in 1993 to between $700 and $800 million last year, and is projected to reach $900 million in 1998.

Checkpoints, which force everyone on the road to pull over and be inspected, are particularly visible symbols of the crackdown. The Border Patrol has 39 of them nationwide, some temporary, some permanent, and not all of which are open at any given time. Most checkpoints are on major roads within 100 miles of the Mexican border, although at least one, in Miami, Oklahoma, is located far inland. The two major checkpoints in Southern California, on I-5 near San Clemente and I-15 near Temecula, have been in existence for decades. But as the local population has grown, and as the Border Patrol has begun operating the checkpoints full time, delays have increased. Drivers now frequently must wait 20 or 30 minutes to get through the San Clemente checkpoint.

The California checkpoints have been blamed for scores of accidents and deaths over the years, mostly from chases on back roads, which smugglers use to avoid the checkpoints. In 1992, a 16-year-old smuggler driving a car full of illegals led agents on a chase into a school zone in Temecula. He plowed into another car and two students walking to school. Four students, one adult, and one of the illegals were killed.

The tragedy prompted some to call for the checkpoints to be closed. While that didn’t happen, the Border Patrol now turns pursuits over to other law-enforcement agencies when it deems them too dangerous to continue. Still, says Temecula Mayor Patricia Birdsall, “It’s a smoldering fire. If we have another high-speed chase or someone gets hurt, it’s going to blow up again in our faces.”

In Arizona, the temporary checkpoint on I-19 did not become a major issue until 1996, when the Border Patrol began receiving enough resources to operate it full time. Locals say this has turned the neighborhoods around the checkpoint into drop-off and pick-up points, creating problems where there were none before.

“One day a few months ago, my daughter and other children were getting off the school bus in front of my office when a group of illegal aliens came up out of the wash next to them,” says Tubac real-estate developer Gary Brasher. He says he saw at least 23 men jump into waiting cars and drive off.

Brasher, who spearheaded the opposition to the checkpoint, says the increased alien traffic and the inconvenience of having to go through the checkpoint to get to Tucson is hurting business in Tubac, an artists’ colony that depends on tourism. He and others also contend that the checkpoint essentially cedes the area south of the checkpoint to smugglers, and that the Border Patrol’s resources would be better spent stopping aliens at the border.

But Ron Sanders, chief of the Border Patrol’s Tucson sector, rejects that. “We are at the border,” he says. “The checkpoint is part of a four-part strategy that includes border interdiction, checkpoints, airport inspections, and employer sanctions. You take away any one of these, and you hurt our effectiveness.”

Many checkpoint opponents believe there’s something un-American about having to stop and declare their citizenship while driving within the United States. “It’s not the way I grew up, and it’s not what this country is about,” says Paul Hart, a former New Jersey policeman who now lives in Tubac. Civil libertarians also argue that checkpoints are discriminatory because Hispanics tend to be subject to greater scrutiny than Anglos.

The Supreme Court has held that Border Patrol checkpoints, whether permanent or temporary, are legal as long as everyone on the road is required to stop. The law also allows warrantless searches of cars stopped at checkpoints within 100 miles of the border. As for the charge that Hispanics are singled out, the Border Patrol says it considers other factors besides ethnicity — including demeanor and dress — when deciding whether to subject a driver to thorough inspection at a checkpoint.

Brasher and Hart argue that it would be more efficient and cost-effective for the Border Patrol to move the checkpoint between the highway and several other side roads that lead away from the border near Nogales. Congressman Kolbe, a moderate Republican whose district lies north and east of the checkpoint, agrees. “It doesn’t make any sense to have it in one place and wait for all the illegal aliens to funnel through,” Kolbe says.

But Sanders points out that the permanent checkpoints in California continue to catch tens of thousands of aliens annually, despite “everyone” knowing that they’re there. And, despite the denial of funding for permanent checkpoint facilities, he says he intends to keep using portable lights and generators to operate the temporary checkpoint on I-19 on a nearly full-time basis.

Nevertheless, Sanders did take the checkpoint down over the summer. He says this was done not to mollify opponents, but because agents were needed to cover remote desert areas where increasing numbers of illegals have been found dead or dying from dehydration. The Border Patrol is sensitive to charges that the crackdown is responsible for the deaths by forcing illegals to take greater and greater risks in order to enter the United States.

Since late fall, the checkpoint has been back up, but now the Border Patrol rotates it every few weeks between the site near Tubac and another one on I-19 just 12 miles north of Nogales. Protesters say they intend to make sure the checkpoint keeps moving. One young Mexican-American spoke for many of them when he said, as he waited in line at the checkpoint. “We didn’t cross the border. The border crossed us.”

©1998 Miriam Davidson

Miriam Davidson, a correspondent for the Arizona Republic, is examining life in Ambos Nogales, at the U.S.-Mexico border.