Veronica was ten years old when she first went into the tunnels. She insists she wasn’t thrown out of her house or abandoned like many of the other kids who lived with her in the miles of concrete storm channels that run beneath the border between Nogales, Sonora, and Nogales, Arizona. “My mother always was looking for me,” she says. But Veronica preferred gang life in the tunnels to her mother’s cardboard shack. “I just like being a vagrant,” she says with a shy smile.

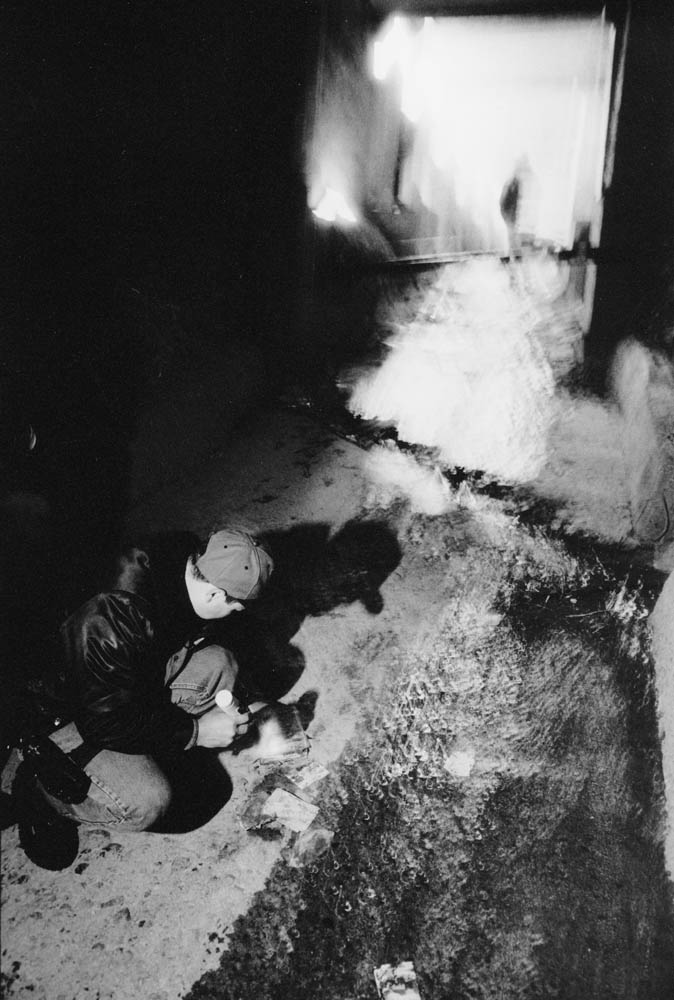

Veronica and her friends call themselves Barrio Libre Sur, the southern outpost of a Latino street gang with branches in Los Angeles, Phoenix, and Tucson. In Nogales, the kids make their living smuggling illegal immigrants through the dark, damp tunnels to the U.S. side. They also beg and steal and sell drugs and some of the girls work as prostitutes, although Veronica says she never has. They use the tunnels to come over to the U.S. side, commit crimes, and go back. Once in a while, they hop freight trains in Nogales, go to Tucson and Phoenix, and stay in abandoned houses while they break into homes of people on vacation to steal TVs, VCRs and stereos. Veronica says she has been arrested many times in both the U.S. and Mexico.

Veronica and the other tunnel kids are among the most lost of a generation of children on the border. They are the sons and daughters of the hundreds of thousands of impoverished Mexicans–often just teenagers themselves–who have migrated here over the past 25 years to work in the maquiladoras, or foreign-owned factories. These kids have grown up in the squalid shantytowns surrounding the maquiladoras, with their parents often split between the border, their hometowns, and the United States. Many maquiladora workers are too poor and too far from their families to provide child care, and so these children have been left to fend for themselves at an early age. “Without a house, without a stable job, without the possibility of social or economic advancement, the family falls apart,” says Alejandro Guzman, director of Consejo Tutelar Para Menores (COTUME), the juvenile corrections office in Nogales, Sonora. “The kids end up in the street.”

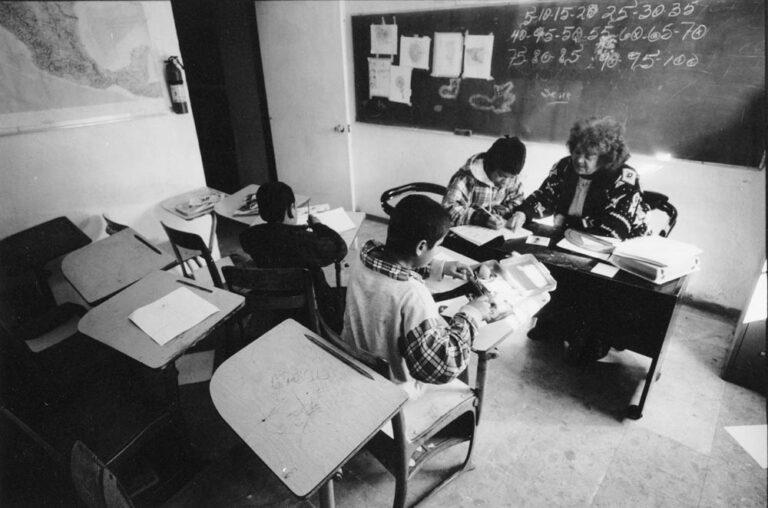

Guzman says his city has seen a sharp increase in gangs, vandalism, drug use, and other anti-social behavior by young people in recent years. “We really weren’t prepared for this,” he says. Given the large numbers of young people in Mexico–half the population is under the age of 20–and the continuing migration to the border, Guzman and others who work with youth in Nogales are sounding the alarm. They warn that unless the entire community joins them in a new effort to provide positive outlets for the kids’ energy, many more will be lost to the border’s thriving criminal underworld.

Veronica’s story is typical. She was born in the Sonoran port city of Guaymas, and came to Nogales with her mother when she was four, after her parents divorced. She grew up shuttling back and forth between Nogales and Guaymas and managed to complete only four years of school before dropping out. In the tunnel, Veronica says she found a gang of kids who made her feel cared for and safe. “Some of the boys were really bad criminals but others protected us and wouldn’t let them touch us.” She says no one forced her to have sex or do drugs until, at age 13, she decided she was ready. She liked the rush she got from inhaling paint thinner and the money she made guiding illegals through the tunnels. She says she tried working in a maquiladora, but was fired after one month for fighting with another girl. Besides, it took her a week of factory work to earn the $35 or $40 she could make in less than one night in the tunnels.

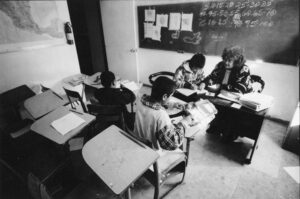

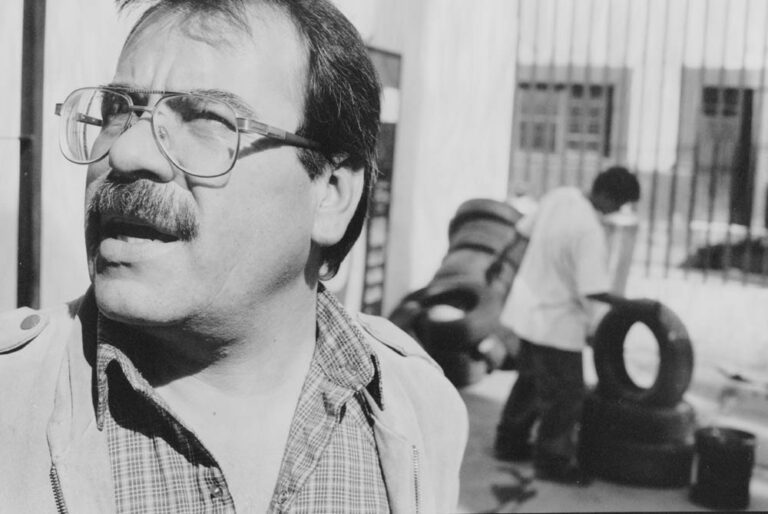

Gang life in the tunnels reached its heyday in the mid-1990s, when scenes of rival gang members inhaling thinner and then attacking each other and their illegal immigrant clients with fists, knives, rocks, and guns appeared on the national news in both the U.S. and Mexico. Crime and vandalism reached record levels in Nogales, Arizona, which has a population of 20,000, less than one-tenth that of Nogales, Sonora. After residents there demanded that something be done, U.S. and Mexican authorities launched a binational effort to control the tunnels. U.S. Army engineers erected huge, metal doors to prevent easy passage from one side to the other, and the U.S. Border Patrol and Grupo Beta, an elite Mexican police force set up to protect migrants from border bandits, began conducting regular sweeps and arresting everyone in the tunnels. Some gang leaders received long prison sentences in Arizona or Sonora. The crackdown also had a humanitarian side: Using funds from an Arizona state juvenile justice fund, the Santa Cruz County Attorney’s Office opened a shelter for the tunnel kids in Nogales, Sonora, in November, 1994. The shelter, called Mi Nueva Casa (My New House), provides food, baths, classes, counseling, and other programs to help the kids learn to live above ground again.

The crackdown did reduce crime on the U.S. side, and Mi Nueva Casa has had success in turning some tunnel kids away from lives of crime and addiction. But as a day program administered from the U.S., the Casa is limited in how much it can do. “They have a place to keep the youths busy for a few hours, but not a place where they can stay,” says Guzman of COTUME. When the doors close in the evening, the kids go back on the street or down into the tunnels again. Guzman notes that juvenile arrests in his city went up by more than 30 percent after the border crackdown, from 1,120 in 1995 to 1,475 in 1996, and continue to remain high. These figures demonstrate that much more prevention and rehabilitation of young criminals needs to be done on the Mexican side. “Up until now, we haven’t had the resources,” Guzman says.

Resources may now be on the way. In January, 1998, Guzman, Nogales Mayor Wenceslao Cota, and other local and state authorities in Sonora met to announce the formation of a new coalition focusing on youth. The coalition has both law enforcement and social service components, and seeks to involve the private sector, as well as community groups, in creating new social, artistic, and recreational outlets for young people. Using federal, state and local funds, the city has launched a program called Rescate (Rescue) which provides teams of police and social workers to go into schools and neighborhoods, identify troubled kids, and educate both parents and children in how to prevent delinquency. “I have hope that, with these programs, the problems of anti-social conduct will be reduced,” says Mayor Cota, who himself used to work in juvenile corrections. “Of course, for any program to succeed, we need to involve the family, the teachers, and the whole society.”

As Guzman sees it, the problem of young people going astray reflects a loss of social, moral and spiritual values. The situation is exacerbated on the border, where maquiladoras have caused widespread social dislocation and where the temptations of U.S. consumer culture are strong. “The border is the door to the rest of the country, and so many problems manifest themselves here first,” Guzman says. Yet Guzman also believes that the border’s proximity to the U.S. benefits northern Mexico and that his country can learn a lot from its more technologically advanced neighbor. “We are 20 years behind the United States, in terms of prevention,” he says. “We need to go beyond the outmoded ways we have of dealing with youth, such as paternalism, while still preserving Mexico’s traditional values of respect for family, culture, nation, and religion.”

Nogales’ churches have, in fact, taken a leading role in this new effort to combat delinquency. The Salecinian Society, a Catholic organization that focuses on children’s issues, recently announced plans to build a large youth center in one of the city’s poorest neighborhoods. At the same time, the Ministerial Council, which represents most of the Protestant churches in Nogales, is buying a farm outside of the city where kids will be able to undergo drug rehabilitation while they study, do chores, and learn a trade. A structured, rural setting such as this may be the only chance for some tunnel kids to lead a normal life. As it is, their nightly use of inhalants prevents them from remembering what they have learned from one day to the next. Some already have permanent brain damage.

Veronica says she’s noticed she forgets a lot of things, and that is one reason she’s decided to go straight. More importantly, at age 18, she is now the mother of two little girls, a 2-year-old and a 2-month-old. She and her children are living with her mother and, with the help of Mi Nueva Casa, Veronica has enrolled in beauty school. The Casa pays for her tuition and a staffer makes sure she attends by taking her there every day. She says she misses her vida loca (crazy life) in the tunnels, but is scared to go back. Last October, when she was 7 months pregnant, she was arrested in the tunnels and they threatened to take her baby away. “Before, I didn’t care about anyone but myself,” Veronica says. “Now, I have lots of reasons to change my life.

“Look at how fast she’s growing,” she says, as she watches her 2-year-old daughter. “What’s she going to think of me when she gets older?”

©1999 Miriam Davidson

Miriam Davidson, a freelance writer in Tucson, is researching the border town of Ambos Nogales.