Memphis, Tennessee – Bronze dogs guard the neo-classical facade of the Shelby County Juvenile Court. Mahogany desks and softly-lit oil paintings grace the administration offices. It is immaculate, from the gleam of the main lobby floor to the glare off the bullet-proof glass that seals the detention section.

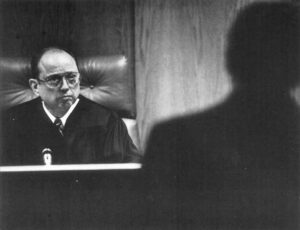

Judge Kenneth Turner wouldn’t have it any other way, explains Charles Gray, chief probation officer, as he leads a tour of the empire Turner has ruled for 30 years in a place where the power politics of child welfare are stark enough to illuminate blind spots in a national debate about reform.

Photo by The Memphis Commercial Appeal

Behind the locked door of a shelter unit in the detention wing, the tour stumbles on a child. He is a small black boy in drab detention clothes with a look of desolation beyond grief. Asked his age, he holds up eight fingers. Asked his name, he whispers so softly Gray has to bend double to hear him.

Freddy Robinson, Gray’s staff reports later, is a foster child with a speech impediment, dyslexia and “periods of outrage.” When an ice storm knocked out power to his state-supervised foster home, the foster mother said he had to leave the house and the boy became distraught. So she took him to the nearest police precinct.

“He was crying and screaming—he wanted his brother,” police officer Ruth Hawkins recalls. “He wouldn’t talk to us. He was out of control.” Officers arrested the sobbing eight-year-old for disorderly conduct, she says, and took him as a delinquent to juvenile detention.

Photo by Donn Jones

Freddy is one of about 500,000 children in this country living apart from their parents, a number that has risen by 63 percent in the last ten years. Despite decades of reform efforts, from class action lawsuits to major federal legislation, the foster care system routinely harms those it is supposed to help. Many foster children live out their childhoods from placement to placement, never returning home or finding any other permanent family.

Among young people who recently aged out of the system, which costs $11 billion a year, a 1991 national study found half were unemployed, 46 percent were high school drop outs, 40 percent were on welfare and a quarter had been homeless for at least one night. Teenage girls leaving foster care were 60 percent more likely to have a baby out of wedlock than their peers, the study found; many of these babies end up in foster care, too.

On paper, Al Gore’s home state is in the vanguard of a national movement of “family preservation” to reverse the dramatic growth of foster care. Tennessee’s “Home Ties,” a program of short-term, intensive intervention for families with children at imminent risk of placement, is listed by child advocacy foundations as a national model. The state’s ambitious “Children’s Plan,” launched five years ago by an alliance of fiscal conservatives and advocates for children, ostensibly overhauled the financing and delivery of services to reduce the number of children going into custody.

But the number of children in the custody of the Tennessee Department of Human Services has continued rising — to 9,024 children in January, up from 7,707 the year before. The publicized reform efforts also seem marginal to the harsh political and economic forces that rule these children’s lives.

Here, as in the nation, children at risk of foster care mainly are the children of the poor. During most of American history, the relationship between poverty and family break-up was unambiguous: with no public relief, parents too poor to support their children had to put them into orphanages or up for indenture or adoption. Indeed, modern day welfare — Aid to Families with Dependent Children — had its origins in a movement to keep children of destitute widows out of state orphan asylums. Federal foster care funding still puts what a top Washington staffer calls “a bounty on poor children,” because local foster care costs are matched only for children from AFDC-eligible families.

Yet—except for the call by right-wing commentator Charles Murray to open orphanages—the national debate about welfare reform has been largely silent on the fate of children whose parents pass a proposed two-year limit on benefits and remain jobless The “family preservation movement,” the latest crusade in the long struggle to make America’s child welfare laws live up to their benevolence, also is silent about the link between rising foster care caseloads and two decades of deepening income inequality.

“When Americans talk about poverty, some things remain unsaid,” writes Michael B. Katz, a social welfare historian who co-directs the Urban Studies program at the University of Pennsylvania. “Mainstream discourse about poverty, whether liberal or conservative, largely stays silent about politics, power, and equality. But poverty, after all, is about distribution.

“Descriptions of the demography, behavior, or beliefs of subpopulations cannot explain the patterned inequalities evident in every era of American history. These result from styles of dominance, the way power is exercised, and the politics of distribution.”

In Tennessee, the politics of distribution in child welfare are hard to ignore. “We were pretty naive when we started,” sighs Nancy Thomas, state coordinator of the Children’s Plan. “Conflicts of interest? We discover one a day…the politics are horrible. Sometimes I feel I’m bare-breasted to the world.”

One rural juvenile judge here owns a residential treatment center, she noted; his cousin, a legislator, has a financial interest in a hospital that collected children from juvenile court by the vanload, to the tune of $501 per head, per day. Another judge is on the payroll of a for-profit psychiatric hospital that has done a brisk business in court wards in a state that in 1989 had the nation’s second-highest rate of child psychiatric hospitalization.

And then there is Judge Kenneth Turner. He was years ahead of the curve in cracking down on “deadbeat dads,” assigning paternity to out-of-wedlock children, and privatizing public services — all elements of the welfare reform proposals under discussion in the Clinton administration. But the results might give advocates pause.

Turner has used child support enforcement to build a personal empire of patronage and political clout from a juvenile court where critics say poor people have few rights and poverty is often punished by jail. Meanwhile, with state AFDC benefits that are among the lowest in the nation, welfare rolls and out-of-wedlock births have continued to soar.

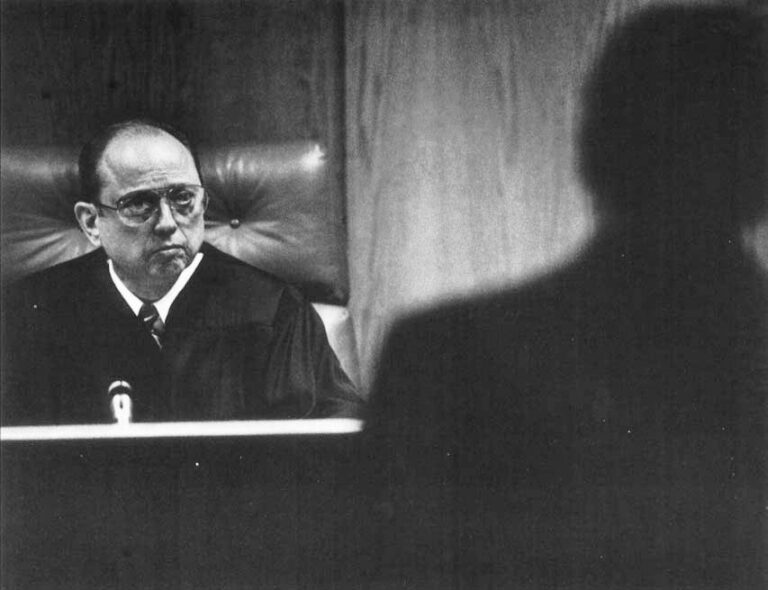

A former vice squad captain who earned a night-school law degree, Turner was never admitted to the bar, so he appoints six referees to hear all cases under a system he devised 19 years ago to circumvent a ruling that juvenile judges had to be lawyers. One referee, Curtis Person, is also a state legislator, head of the Tennessee senate’s judiciary committee and the top power broker in the Republican party. With state money and legislative blessing, Turner commits juveniles not to state reformatories, but to private institutions he himself lobbied to establish. They are owned by Corrections Corporation of America, a profit-making company whose early stockholders included top state officials of both parties.

The director of juvenile court services is Turner’s son-in-law Jerry Mannis; the clerk of court, Bob Martin, was Turner’s appointee until a lawsuit forced him to run for election, when he won with Turner’s political endorsement.

“Judge Turner has his own prosecutors, his own defense counsel, his own bailiffs,” observes Walter Evans, a civil rights attorney recently appointed a city judge by the Memphis mayor. “Their boss is Turner. A lot of people who work at juvenile court are relatives and friends of County Commissioners. The juvenile court’s tentacles are spread so wide, no one wants to rock the boat.”

Many on the staff of 320 are paid out of the five percent administrative charge kept from the court’s collection of $41 million-a-year in child support — a business that now dwarfs more traditional juvenile court activities. Collection methods have long made Turner the chief prosecutor, judge and jailer of legally unrepresented men who have fallen behind in support payments, often because of unemployment or adversity in a city where black joblessness is triple the white rate and the gap between black and white household income is the steepest in the nation.

“A man who won’t support his family is the lowest form of human life,” asserts Turner, who knows his flagship issue appeals to poor black mothers and white conservatives alike. “We do have a reputation for strict enforcement. I don’t respond to criticism; the record speaks for itself. If I’m wrong, they can appeal it.”

In fact, protracted appeals have repeatedly found Turner’s practices wrong. But, helped by his clout and deferential press coverage, his critics contend, Turner has side-stepped any substantial change. Martin, Turner’s clerk of court for 21 years, doesn’t disagree. The rulings “have had no profound impact,” he says. “There’s more than one way to skin a cat.”

To avoid the due process requirements and time limits required by one court ruling, for example, Turner’s referees stopped issuing criminal warrants for non-paying parents; instead they issue “attachments pro corpus,” civil orders more commonly used to repossess a car or piece of furniture than to arrest a human being. More than 2,000 people went to county jail on such attachments or other support-related orders from juvenile court last year.

“We have not evolved that far from the plantation state,” observes Wayne Chastain, a former Memphis Area Legal Services lawyer who has been winning largely empty victories against Turner’s procedures for 16 years and has a lawsuit pending now in federal court. “Prior to the Civil War, slaves were considered chattel and they could be attached; these men can be seized as though they were slaves.”

Though most cases involve men, Chastain’s first three concerned absent mothers. Juanita Martin had left her children in her mother’s care while she took government-sponsored training in Mississippi to become a licensed practical nurse. She was summoned to juvenile court and threatened with jail if she didn’t sign an agreement to pay $25 a month in child support to offset the AFDC benefits the grandmother received for the children. When she fell into arrears, she was jailed twice in nine months while trying to finish her training. “The grandmother would have to go down with the AFDC money to get the daughter out,” Chastain recalls. “It became sort of a joke.”

Another mother, Denise Crump, was summoned to juvenile court from the mental hospital where she had been admitted as a condition of keeping her two children out of foster care. She, too was threatened with jail if she didn’t make payments through juvenile court to offset the AFDC they received at their grandmother’s.

In a later case, a father with low earnings but a good payment history fell into arrears when he changed jobs and his new employer failed to honor a wage assignment. The father, Freddie Sevier, was summoned to court, judged guilty of civil contempt — without being given a right to counsel — and sentenced to jail indefinitely unless he made a $200 purge payment, court records show. Unable to pay, he spent sixteen days in jail before a referee ordered his release, and his new employer discharged him for absenteeism.

In 1984, a US Court of Appeals ruled Sevier had been entitled to a lawyer and found that prosecutorial actions by Turner and other judicial officers, if proven, would expose them to liability for damages. Sevier settled for $5,000. Six years later, Criminal Court Judge Joseph E. Brown heard petitions from 22 men jailed by juvenile court and concluded that despite cosmetic changes, the system was as fundamentally unfair as ever.

“Twenty-seven years is long enough for somebody to get their act together down there,” Brown fumed from the bench when Turner stonewalled his hearings on the matter. “In the United States of America, a citizen…is not supposed to have the same man charge him, arrest him and try him — or the agents of the same man. That’s un-American.”

For that remark and others, Brown was slapped with a formal reprimand from the state judiciary review board last year for “willful misconduct”– making derogatory comments about a colleague from the bench. He’s appealing.

Brown says parents arrested because of child support debts are pressed by bailiffs to sign a form waiving counsel before they even see a referee. In February alone, a third of the 733 parents who appeared were found guilty of contempt. Court officials say about half of these came up with a “purge payment” of $200 to $500 to buy time; the rest — about 115 men — went to jail, where their support arrearage grew along with a new debt for jail and court costs. Such men are generally released within a week or two — but only until the next summons, when it all begins anew.

“It’s a travesty masquerading as a court,” charges Brown, an African-American nationally known for innovative sentencing. “But people are afraid of him. People say, “Turner’s a powerful man — he’ll ruin you.’ Nobody ought to be so entrenched that they can operate above the law.”

Turner’s stature as a Memphis institution apparently was unshaken by the revelation a few years ago that his entourage made freewheeling use of six $10,000-limit credit cards issued by the county. The bills, paid without question by the County Commission as juvenile court expenses, included thousands of dollars in out-of-state air travel and entertainment at such places as the Hard Rock Cafe in Los Angeles, a Bourbon Street bar in New Orleans, and an east Tennessee hunting resort where some of Turner’s 350 “auxiliary probation officers” were wined and dined for three days.

“We don’t review their books in detail,” shrugs Walter Lee Bailey, a civil rights veteran and one of four blacks on the the 10-member County Commission that approves the court’s $18 million budget. “We basically grant them the assumption that they operate within good administrative policy if they don’t give us a deficit.

“The Commission is not the policeman of any abuse as long as it isn’t flagrant,” he adds, pouring himself another glass of wine during an evening interview that has moved from his high-rise law offices to a blue velour-lined mobile home parked below. “Hell, I don’t know if it’s abuse. If I saw a credit card charge at one of the casinos, maybe, but if it’s a convention — who am I to criticize?”

Turner’s volunteer probation officers have included a number of prominent businessmen — and at least one suspected pedophile. “We have investigated some of the people that he has working as auxiliary officers,” police sergeant Claudette Boyd of the Memphis sex crimes unit acknowledged. “But it’s like the cases fall off the end of the world.”

Two years ago, she said, a teenage boy made a statement to her describing sexual abuse by his volunteer probation officer over an extended period, including sexual molestation during an out-of-state trip to a log cabin summer retreat. The boy said he decided to come forward when his probation as an “unruly child” expired and he realized other children were going into the same man’s care. But Boyd was unable to interview the suspect about the charges. “He got a lawyer and said he wasn’t coming in,” she recalled.

Despite her written report to the county attorney general’s office, she said, the case was dropped without further investigation. Robert Carter, the assistant attorney general in charge of child abuse prosecutions, confirmed that the case was never given to the grand jury, but blames insufficient evidence and a lack of resources. He doesn’t know whether the suspect is still an active volunteer, he added, and if he did know, couldn’t tell because of confidentiality.

“Juvenile court sets its own rules, day by day,” sex crimes investigator Boyd observed. “That’s just the way it is. Everybody knows it, everybody plays by those rules. Since the whole state of Tennessee hasn’t done anything, what’s one person to do?”

Turner’s usually gracious tone turns steely when he is asked about this case. “That’s really muckraking,” he protested. “A lot of false, malicious accusations are made. Kids have various reasons for making this accusation.” Over the years, he said, “precious few” sexual abuse allegations have been made against volunteers and all have been disproven on investigation. Earlier, sitting in his imposing office across from a portrait Abraham Lincoln, Turner lamented the passing of “a kinder and gentler time in our community.” He dates the breakdown in respect for authority to 1968.

That’s the year Martin Luther King came to Memphis, answering the call of striking black sanitation workers whose struggle embodied the new direction King was seeking for the civil rights movement — a Poor People’s Campaign that would force America to confront economic inequity.

The Memphis garbage workers had full-time wages so low they qualified for welfare, job conditions cruel enough to scar them, body and soul: No set quitting time, nowhere but the street to relieve themselves, no place to wash the smell of refuse from their skin, no pay when they were injured on the job. Their walk-out finally came after two men were crushed to death in the maw of a garbage compressor. In marches to an intransigent city hall, their signs cried out “I Am A Man.”

When leaders of the protests called on school children to join the demonstrations each Monday instead of going to class, Turner threatened to jail the parents of truants. He still blames the demonstrators for “exploiting children and teaching them to disrespect authority.”

Bypassing a lobby filled with black families, he takes a security elevator to a private dining room to share stew and warm cornbread with four of his referees, all white men. While Turner smiles approval, they speak of his accomplishments: 94,000 children “legitimated” through paternity actions over 30 years, child support collections 80 times higher than when he started, an annual breakfast for volunteers that draws 1,000 workers who are paid only in “psychic money.”

They speak dismissively of lawyers who criticized the court before being fired or leaving town. One they speak divisively as a cocaine addict, another as a deadbeat dad. Turner has been known to depict other adversaries as Communist, homosexual, or dangerous lawbreakers.

The judge is a longtime admirer of J. Edgar Hoover and reputed to have the late FBI director’s skill at leveraging other people’s secrets. He has been re-elected unopposed since his first race in 1963; his current term runs till 1998. Asked if his thinking has changed in 30 years, he replies, “Not really,” then amended his answer. “More parents ought to be jailed for child neglect,” he said. “We’re taking these kids and raising them and letting the parents go scot-free.”

It’s a view antithetical to the “family preservation” philosophy of the Children’s Plan and Home Ties. “Oh dear, dear, dear, dear, that sounds so harsh, bless his heart,” Trudy Weatherford, state coordinator of Home Ties, said when the remark is repeated to her.

Like many officials, Weatherford once worked for Turner. “He truly cares about children,” she insisted. “On the other hand, he certainly has built himself an empire. He certainly is all-powerful in Shelby County. There are no checks and balances and haven’t been for a long time. We pick our battles carefully.”

Weatherford said Turner has welcomed Home Ties as a resource. She observes that in some respects the program represents a return to “good, old-fashioned social work.” And she likened child welfare prescriptions to fashions in clothing. “They come and go,” she said with a laugh, “But Judge Turner stays forever.”

@1994 Nina Bernstein

Nina Bernstein, a reporter for Newsday, is investigating foster care in America.