Shirley Wilder still carries scars from her first weeks at the New York State Training School for Girls in Hudson, where she was sent soon after her 13th birthday.

“There were girls there 15, 16 – oh, man, the way they treated me!” she remembers 21 years later. “Seven of them held me down. They took broken glass and cut my arm because I wouldn’t go to bed with one of them. But the staff put me in the hole because I started fighting.

“The dark room – no windows, no screens, sleep on the cold floor,” she goes on, her hands sketching a box-like cell. “The counselors would hit you like you were a man. There was the Behavior Modification Unit. We had to mop the corridors and the bathroom on hands and knees with a rag. We was nobodies.”

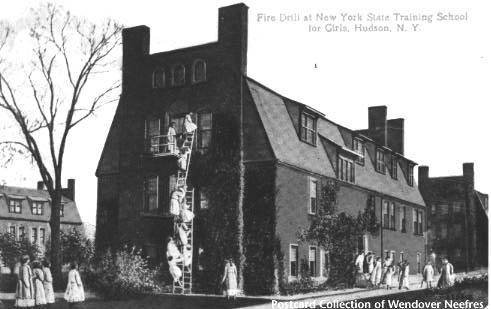

The red brick buildings of the former Training School for Girls at Hudson stand on a 168-acre bluff overlooking the Hudson River valley, between the Catskills and the Berkshire mountains. It is a men’s prison now. The old chain-link and barbed-wire barrier that confined some 200 girls here in Shirley Wilder’s day has been supplanted by 16-foot double fences topped with loops of razor ribbon. But the fourteen brick “cottages” that housed 25 to 30 girls each have barely changed since the oldest ones were built more than a century ago.

Off a dirt road on the grounds, there is a small cemetery. The graves lie hidden in a grove of cedars at the edge of a wooded ravine, the markers so tilted by winter thaws that they look almost scattered. Lily of the valley grows wild here; the small, shapely green leaves push through rough grass and disappear into the dark underbrush of the steep drop. There are no dates on the weathered gravestones, and no epitaphs; only girls’ names, fading from bare limestone.

Lizzie French. Nellie McGovern. Anna Schaberger Julia Coon. Mary O’Brien. Helen Peer.

“It’s like being somebody thrown away,” the superintendent of the prison murmurs into the stillness where a dozen names bear mute witness to generations of nobodies who passed through the same gates as Shirley Wilder.

Who lies in the graves under the cedars? In one story passed along by former housemothers to their prison guard sons, these are the dead babies born to girls confined here long ago. In another version, used for years to frighten living children, they are girls killed trying to escape.

“There were stories, if you ran away, the dogs’d get you in the woods,” remembers Tom Tunney, who was the last superintendent of the training school before it closed it 1976. “You know,” adds Gale Smith, his former assistant, who still works for the state Division for Youth, “If kids misbehave, things happen to them and they get buried here.”

It seems only right that babies and bad girls should converge in the mythology of the lost graveyard. The connection is at the heart of this institution’s origins, and it haunts the history of child placement, from reformatories and foundling asylums to adoption agencies and “residential treatment centers.” It is the buried link in the recent resurrection of an orphanage ideal in a time of renewed attacks on welfare and unwed motherhood.

Any era’s definition of acceptable female behavior intersects with its standard for removing children, and shapes its versions of substitute care. American child welfare reform has long see-sawed at this nexus, bumping against economic realities (e.g., substitute care always costs more than family subsidies), and against the unyielding facts of child development: a need for intensive human attachment, the trauma of childhood separations, the rapid transformation of yesterday’s children into today’s child-bearers.

The central ideological conundrum in welfare policy has been how to reconcile punitive “deterrence” of dependent poverty in parents – especially women – with the promise of equal opportunity for poor children. The stronger the desire to discipline society, the stronger the appeal of schemes that claim to rescue poor children by removing them from their failing families.

“It’s so easy to hate the adults,” Tunney muses. “When kids would come, we’d say, ‘Oh, those terrible parents.’ And yet these are the same damn parents who went through my facility as kids.”

When the stone and wrought iron gates first swung open here on May 7, 1887, the place was called the New York State House of Refuge for Women. But “refuge,” like “cottage,” can be misleading. To excavate the history of this institution is to sift through layers of such euphemisms, the sediment left by successive waves of sweeping reform, and to discover that the hard-edged realities beneath remained astonishingly consistent over a hundred years.

The first inmates to enter the gates were two local women convicted of prostitution – “the very lowest lewd women to be named,” the Hudson Daily Evening Register reported. One was described as “a ‘soiled dove,’ a married woman named Minnie Hoetzel,” with “respectable parentswhom she daily disgraced, and a husband who would not and could not live with her.” The other was Mary Schermerhorn, a girl from the nearby town of Kinderhook. “As to the Schermerhorn girl we have no knowledge other than that she was a ‘bad girl’ with no prospect of reformation,” the paper reported before segueing into a promotion for ladies’ bonnets.

Seventy years later, a three-part series in the New York Daily News was headlined “Last Stop for BAD Girls” in the lurid lettering of a B-movie poster. “Hudson is where a ‘bad girl’ goes when nobody else will take her,” staff reporter Kitty Hanson wrote, citing as examples “Mabel, unwed mother of two and only 14 years old,” and “Erda, hanging around bars at 12, a sexual delinquent at 13.” The series was laced with suggestions of unbridled sexuality: a cottage “housefather” driven to ban straight skirts because residents wear them “so tight their panty seams show”; the “raucous laughter of half-a-dozen gym-suited girls” at a sunset baseball game, where, “between innings they panted and yelped in tumbling exhibitions and wrestling matches” to the sound of “the inevitable rhythm and blues beat that seems to have found the pulse of these kids who won’t conform.”

No very sophisticated feminist analysis is needed to recognize through the titillated Puritanism of such accounts that Hudson served partly as an enforcer of patriarchal authority over “loose” females, from the “soiled dove” who had flown her husband’s coop, to “wayward” adolescents on the run. Generations of local girls remember being kept in line with the threat of the training school if they were naughty.

Like so many other newspaper stories about “bad girls” before and since, the 1957 series maintained that those of its own time were worse than their predecessors, and warned of a growing trend toward more “masculine” crimes of violence by young girls.

But fifteen years later, when Shirley Wilder arrived at Hudson, 90 percent of her fellow inmates were still “persons in need of supervision” – truants, runaways and throwaways from the foster care system. Like Shirley, a motherless runaway from an abusive home, many were there by default because no private agency or relative would take them.

“It was terrible, the backgrounds of these poor children,” sighs Nancy Scalera, a former cottage supervisor; her son, the part-time mayor of Hudson, works as a guard at the men’s prison, where one inmate claims to be serving time in the room where he was born. “Their home life – you could almost see why they had to run away.”

No home Shirley Wilder had known in Harlem came close to middle class ideals of domestic order, comfort or security.

In the rhetoric of the institution, her cottage was supposed to fill that gap. But the descent from rhetoric to reality was a precipice.

Peeling paint, cracked plaster and gaping holes marked the walls. The kitchen, dining area and common room for the 25 cottage residents were in a dingy basement. At 8:30 p.m., they were shut into their individual bedrooms. In the dark hours before the 6:30 a.m. wake-up call, sleep was broken by the sound of urgent knocking, as girls who had to use the toilet tried to draw the staff’s attention. The long list of rules tacked inside each door included “Never leave your room without first getting permission of the staff on duty. (Knock on door.)”

There were 33 other basic rules on the list, some broad, some oddly specific. “Do not be disrespectful to any staff;” “Do not talk unnecessarily after prayers are said;” “Do not use profanity at any time;” “Do not wash personals in A.M., only when they are stained.” If you broke the rules, there were rules for punishment – “No talking when serving room confinement – rule of silence.”

“Although it is widely believed that an institution organized on the cottage system provides the physical environment for a homelike experience, the inescapable fact is that a cottage that houses twentyor more inmates can never be homelike, no matter how many homelike touches are added,” sociologist Rose Giallombardo concluded after studying Hudson and two similar girls’ reform schools in the West and Midwest between 1968 and 1973. “The sense of constraint, inherent in mass living under regulated authority, permeates the institutions.

“Individuals who are not familiar with the day-to-day operationnaively assume that the staff in so-called treatment institutions dispose of situations involving rule infractions by sitting down with the inmates to talk it out. This is simply not so. At all three institutions, the initial response of the staff was always punitive segregation.”

What Shirley called “the hole” was a section of the institution’s old hospital building, where girls were locked in isolation cells for days at a time. Reasons for solitary confinement were many. “Weird behavior, fighting; running away,” Joann Concra, a staff member in the late 60s and early ’70s, recalls. “Perhaps someone got a sad letter from home and was threatening to kill themselves – your mother dies, you’re 13 years old, you’re locked away, that can be pretty traumatic.

“The room was padded. There was nothing on the floor. As your behavior would get better, you could get a mattress. It was like, it’s 7 now o’clock, you want to sleep on a mattress, you calm yourself down. You’re hollering, you’re cold – you stop hollering, we’ll give you a blanket.’ Then, say, like three days had passed and she cooperated and she’s starting to come around, she’s starting to act like a human: Maybe we’ll let you have sheets.”

Girls were stripped of their clothes before being placed in solitary, and dressed in pajamas with velcro fastenings so they couldn’t use metal snaps or buttons to harm themselves. Part of Concra’s job was to look through a peephole every ten minutes and record any unusual behavior, like “sitting in a corner and rocking or holding the knees, or beating your head against the walls.” There were up to 20 such cells; when they were full, cottage rooms could be stripped bare to serve the same purpose.

A century earlier, solitary confinement also had been the preferred mode of treatment at the House of Refuge. “Though I have been very much impeded by the newness of the institution in my desire to enforce rigorous discipline,” Sarah V. Coon, the first superintendent, reported in November, 1888, “still so far as it has been possible in our overcrowded prison, I have tried to isolate each girl, upon her arrival, from the older inmates. Sometimes, upon detecting a developing tendency to misbehave, I still keep her in solitary confinement until I see a change in this respect. Besides solitary confinement, confinement in dark cells, with disciplinary diet and handcuffs, is in vogue.”

The State Board of Charities, quoting the superintendent’s account in its 1888 annual report, was at pains to prevent any misunderstanding about the nature of the institution, then surrounded by a high board fence. “It is not a prison, nor are the possible long terms of detention intended as a punishment, but to allow sufficient time for the discipline and training to have an effect upon the character of those subject to them. It is an educational institution.”

This is a theme that runs relentlessly through the history of institutions dedicated to the reclamation of young people. The formula’s contradictions were under broad attack by the time Shirley Wilder arrived at a “school” where one cottage housemother kept order with a baseball bat, and unpaid labor in the institution laundry took precedence over classes.

A new wave of historians and sociologists and a series of landmark civil liberties cases in the 1960s had argued that noncriminal “prisoners of benevolence” suffered more abuse and greater deprivation of liberty in the name of treatment than anyone could justify in terms of punishment.

“It is not normal for society to love the socially helpless,” Ira Glasser, now director of the American Civil Liberties Union, warned in 1974. “Who lovesthe troubled children of the poor? The record of public charity is an unloving record of punishments, degradation, humiliations, intrusion and incarceration.”

Tunney, 72, recalling failed reforms from the tranquility of retirement, confesses, “We did a lot of damage to kids, no question about it. What one does in institutions is to begin to deal with problems that were not problems before the child went to the institution.

“Everybody knows whether your shirttail should be in or out and your hair combed and whether you should swear. Nobody knows how to deal with a girl’s sexual promiscuity. So you set up rules around shirttails and swearing and the things you know, and then you start to get children punished for breaking those rules. And you can sit there and see that it isn’t doing a damn bit of good. But” – his reedy voice turns hesitant – “I guess it’s better to try.”

Outflanked by civil libertarians in the ’70s, Tunney’s generation of reformers now feels battered by the backlash. “I’m so glad I’m out of that business,” Tunney says. “Nothing’s changed. The pendulum swings – I lived long enough to see it.”

Smith, who served as superintendent of a girls’ reformatory near Albany that has replaced Hudson, has watched much of his life’s work undone. “In the division [for youth] we struggled for years to reduce the size of our facilities, to have nothing bigger than 100 beds. Now we’re moving in the opposite direction. Some are over 200. One is close to 300. I cling desperately to some of the changes we were able to make. Sometimes they seem very minuscule.”

In many ways, our own times now resemble the times that created the Hudson House of Refuge.

There was intensifying middle-class alarm over “pauperism,” crime, and family breakdown. The fragility of American prosperity had been exposed by a deep depression, violent strikes, mass immigration, and the disorder of cities glutted with the casualties of economic upheaval. Unwilling or unable to grapple with the structural roots of unemployment, a new breed of “scientific” social reformers focused increasingly on family patterns as the primary source of poverty, and on the supposed role of indiscriminate charity in perpetuating those patterns. Poor women and children became the targets of intense new efforts to create welfare policies that would promote social order.

By the 1870s, fears about the formation of a permanent class of paupers and criminals had turned an older cult of true womanhood on its head: the “fallen woman” was seen as the progenitor of idle and vicious generations who drained the resources of the Republic and threatened its stability.

“One of the most important and most dangerous causes of the increase of crime, pauperism and insanity, is the unrestrained liberty allowed to vagrant and degraded women,” social reformer Josephine Shaw Lowell told the New York state legislature in 1879, in arguing for the creation of the state’s first reformatory for women.

It was targeted at “young girls of immoral character, habitual drunkards or those guilty of misdemeanors.” Before the reformatory experiment these young women – l5-to-30-year-olds typically convicted of prostitution or vagrancy – had been subject to terms of ten days to six months in a local jail, or half a year in a county poorhouse. Afterwards, they were sentenced to Hudson for five years, with earlier release entirely at the discretion of their keepers.

“The advantage of this,” argued Lowell, the first woman on the State Board of Charities, “is that, at least during that five years, she is not degrading herself and injuring the community by a career of viceor resorting to the poor-house when needing rest for several months at a time; nor can she, while in the refuge, become the mother of beings destined to a life as wretched as her own, and dangerous to the community.”

Lowell, who wanted to eliminate poverty, not lust cope with its consequences, cited cases of women from a state-sponsored study of poorhouse inmates. Nine out of the ten she chose to highlight were mothers of multiple illegitimate children – the stereotypical welfare mothers of their day.

Historians since have found the original survey badly skewed, since it ignored the heaviest users of poorhouses – young men who stayed for short periods during the severe, often seasonal, bouts of unemployment that were an inescapable feature of the era’s economy. It’s an example of how a dominant cultural paradigm can triumph over facts that challenge its assumptions. (Consider the recent government survey that discovered only one in four poor households in New York City was headed by a single mother – a fact so counter-intuitive in the 1990s that it has made no dent in the rhetoric that casts such women as the primary carriers of poverty.)

The House of Refuge embodied all the contradictions of Lowell’s plan for cottages “fitted up as nearly as possible like an average family home” in the shadow of a 96-cell prison. Over time the age of admission shifted downward; the name of the institution was changed; the possible length of confinement increased even as the reasons for commitment grew more nebulous. In 1904, when it became the only institution in the state for the commitment of delinquent girls 16 and under, the authorizing statute encompassed abandoned children, children who went to dance-halls, peddled cigar stumps or scavenged bones from the garbage in the street. Indeed, the list of “principal offenses” was a catalog of middle-class distastes for the pastimes and survival strategies of urchins in swarming tenement neighborhoods.

Eventually the vocabulary used in such statutes changed to “incorrigible,” “wayward,” “truant” and “in need of supervision.” The daughters of native millhands and laborers were replaced by the daughters of immigrants – first Irish and German, then Italians and Russian Jews. In 1906 there were so many “Hebrew” girls, the institution hired a part-time teacher to provide them Jewish religious instruction. Finally came the daughters of Southern-born blacks and “Nuyoricans.” But in key respects, the targets of Hudson’s reformation remained the same for 90 years: Poor, young and “bad” in the way that word has always been applied to females – to signify sexual transgression.

In the 1950s psychologist Gloria McFarland screened infants born to Hudson inmates for signs of retardation that would make them unadoptable. “We had a unit in the infirmary where babies were kept until they were taken away for adoption or foster care,” McFarland recalls. “I didn’t think the children should be there. Weeks would pass. The babies got marasmus – they were depressed because the girls didn’t pay any attention to them.”

Marasmus is a wasting away of the flesh without organic cause, a failure to thrive in the absence of love that can be as fatal for a baby as meningitis. Examining skinny, listless infants in their cribs, McFarland was haunted by the thought of dead babies in the old cemetery. She fought successfully to have the nursery closed.

With the nursery gone, the courts stopped committing pregnant girls to Hudson. Then Tunney and Smith arrived, and decried the lack of services to Hudson inmates who turned out to be pregnant. Private foster care agencies refused to take them. “Some of them had virtually no place at all – they were in the streets without prenatal care. So we created a special unit in one of the cottages where some of the girls could stay in the system,” Smith recalls.

“They couldn’t keep their babies,” remembers Joann Concra, who worked in that unit for a while. “It was very traumatic on the girls.”

These days, as rates of incarceration for women rise, baby nurseries have reappeared at several prisons, including the one at Bedford Hills, NY, founded on the Hudson model at the turn of the century. These days, orphanages are being championed as an innovative solution to out-of-wedlock births and cycles of poverty. Charles Murray, profiled on the cover of the New York Times magazine, declares that he doesn’t want society to tell the young, unwed mother ‘”You made a mistake.’ I want society to say, ‘You did wrong.'”

We are not so far, after all, from the Hudson House of Refuge.

In a sense, its old graveyard doesn’t hold the institution’s failures, but its only clear successes in the original goal of keeping “degraded” women from procreation, and saving the public the burden of their children. But who is really buried here, the babies or the bad girls? For decades the question has been left unanswered, the myths perhaps more useful than the truth would be.

Fifteen gravestones are still standing. Eleven can be deciphered. Six names can be traced to death certificates in the keeping of the Hudson city clerk. Later, in leather bound ledgers stored and forgotten for years in the basement of a state office building in Albany, all the names surface in the flowing script that fills ruled and numbered pages.

Here lies Anna Louise Schaberberger, 5 months old, who died May 7, 1892, on the fifth anniversary of the day the House of Refuge gates swung open. Here, too, lies Anna Schaberberger, the baby’s 21-year-old unwed mother, who died giving her namesake birth. She was inmate number 338, a German immigrant and domestic servant committed from Yonkers for petit larceny soon after she became pregnant by an unnamed man.

Here lies Nellie McGovern, a New York City child of Irish immigrants who was 18 and said to be married when she died here in the winter of 1994, suffering from syphilis and childbirth fever. Of her baby there is no record – or could it be the Michael McGovern who died four months later in Mt. Loretto, Staten Island, site of a Catholic orphanage run by the Mission of the Immaculate Virgin?

Here lies Mary O’Brien, sent to the House of Refuge at 16 as “a common prostitute.” She died of tuberculosis two years later, on September 26, 1894, her occupation listed as “domestic” on her death certificate.

Here, too, lies Lizzie French, who died of TB when she was 17. She was only 14 and listed in good health when she was sent behind the high board fence to be reformed; she had been working in a caramel shop in Troy, New York, and was committed for petit larceny three weeks before Christmas, 1892.

How healthful the site on the bluff above the river had seemed to the founders when they chose it. But by 1899, in its 12th annual report, the board of managers called the need for sewerage urgent, “the dungeonsdamp and cold,” “the ceilings in the main building and in the cottagespoor, many of them having A fallen and others in danger of falling hourly.” Later reports complained of harmful overcrowding, girls sleeping in corridors, and a nearby cement works that emitted “noxious gases and blinding clouds of dust.” Again and again they begged the state legislature for funds “to bring the Institution up to the real purposes of a Reformatory.”

Meanwhile, the ledgers filled with names and numbers, and sometimes another grave was dug.

Julia Coon. She died at 20 in June of 1893, in childbirth, two months after her commitment as “a disorderly person.” An unwed housekeeper, half German, half Irish, she left no record of what happened to her baby or who its father was.

Helen Peer. She died at 21 in the spring of 1896, suffering from syphilis and “chronic diarrhea” – probably typhus. A collar maker by trade, she had been convicted of being a vagrant in Glen Falls, NY, after the bitter depression winter of 1893.

By then, reformer Josephine Shaw Lowell had come to see low wages and unemployment as the primary causes of pauperism. She began to support organized labor and binding arbitration; she raised money for striking garment workers; she organized a consumers’ league to boycott stores that underpaid and overworked salesgirls.

But the Hudson “experiment” she’d launched continued. To be sure, the oversized parole ledgers sometimes reported that a young girl discharged was “doing well” – married, employed as a servant by a “respectable” family, or, more ambiguously, back with her parents. But most entries were less sanguine.

“Dora Millerdid well for a few months, then went back to an evil life,” is the entry on a Jewish girl born in Berlin who “had worked in a collar shop” before spending three years at the institution for disorderly conduct. “Went to pieces immediately after final discharge and now acting disgracefully in Troy,” reads the report on Mamie King, who had spent five full years at Hudson. Edith Dennison, Woodstock native, is “reported by town authorities of Fayetteville pregnant; [they] wish to return Edith.”

By the time Tunney and Smith arrived in 1965, the old ledgers were stacked in the hospital basement, with row upon row of wooden file boxes. The old cemetery was completely overgrown. They tried to combat its fearful mythology by having a group of residents reclaim it from the encroaching woods. Girls cut back saplings and brambles, pulled the weeds, mowed the tall grass down to the ground. At project’s end, they were given cut flowers to place on every grave.

“My impression was that they felt some kind of a link,” Smith says, “because there were kids in similar shoes so many years ago.”

©1996 Nina Bernstein

Nina Bernstein, a writer at the New York Times, examined foster care in America while a Patterson fellow.